Administrative Part 3 Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PPC-Infographic.Pdf

Celebrating our 15th anniversary, Partnership for Patient Care (PPC) is the region’s premier patient safety and quality program driving health equity and high quality outcomes. 115th5th Anniversary 2006 – 2021 WHAT IS PARTNERSHIP FOR PATIENT CARE? Partnership for Patient Care (PPC) is a collaboration between Independence Blue Cross, Health Care Improvement Foundation and the region’s leading healthcare organizations and stakeholders to accelerate the adoption of evidence-based clinical best practices. PPC’s improvement efforts have enabled the region to foster partnerships among organizations that share a common desire for providing the safest and highest quality care to patients. PPC serves as an umbrella, under which several programs have been established during the past 15 years to support ongoing regional improvement. PPC PROGRAMS Health Equity Data Strategy (HEDS) NEW New in 2021, HEDS is a regional collaborative aimed at decreasing disparities in health outcomes with a focus on establishing recommendations for the implementation of a health equity data strategy. This program will support organizations in the accurate and reliable collection of REaL (ethnicity, and language) data, utilization of the data to evaluate health outcomes, identification of disparities across populations and health conditions; and implementation of targeted quality improvement strategies that promote health equity. Safety Forum 100% A forum of front-line patient safety leaders from hospitals across Southeastern PA that of participants rated promotes interactive discussions about safety hazards and vulnerabilities and a peer- the program as very good or excellent to-peer exchange of patient safety approaches, processes, and best practices. Pennsylvania Urologic Regional Collaborative (PURC) 142 PURC is a quality improvement initiative that brings urology practices together in a physician- participating physicians led, data-sharing and improvement collaborative aimed at advancing the quality of diagnosis 17,000+ and care for men with prostate cancer. -

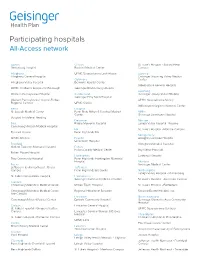

Participating Hospitals All-Access Network

Participating hospitals All-Access network Adams Clinton St. Luke’s Hospital - Sacred Heart Gettysburg Hospital Bucktail Medical Center Campus Allegheny UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven Luzerne Allegheny General Hospital Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Columbia Center Allegheny Valley Hospital Berwick Hospital Center Wilkes-Barre General Hospital UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Geisinger Bloomsburg Hospital Lycoming Western Pennsylvania Hospital Cumberland Geisinger Jersey Shore Hospital Geisinger Holy Spirit Hospital Western Pennsylvania Hospital-Forbes UPMC Susquehanna Muncy Regional Campus UPMC Carlisle Williamsport Regional Medical Center Berks Dauphin St. Joseph Medical Center Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Mifflin Center Geisinger Lewistown Hospital Surgical Institute of Reading Delaware Monroe Blair Riddle Memorial Hospital Lehigh Valley Hospital - Pocono Conemaugh Nason Medical Hospital Elk St. Luke’s Hospital - Monroe Campus Tyrone Hospital Penn Highlands Elk Montgomery UPMC Altoona Fayette Abington Lansdale Hospital Uniontown Hospital Bradford Abington Memorial Hospital Guthrie Towanda Memorial Hospital Fulton Fulton County Medical Center Bryn Mawr Hospital Robert Packer Hospital Huntingdon Lankenau Hospital Troy Community Hospital Penn Highlands Huntingdon Memorial Hospital Montour Bucks Geisinger Medical Center Jefferson Health Northeast - Bucks Jefferson Campus Penn Highlands Brookville Northampton Lehigh Valley Hospital - Muhlenberg St. Luke's Quakertown Hospital Lackawanna Geisinger Community Medical Center St. Luke’s Hospital - Anderson Campus Cambria Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Moses Taylor Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Bethlehem Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center - Regional Hospital of Scranton Steward Easton Hospital, Inc. Lee Campus Lancaster Northumberland Conemaugh Miners Medical Center Ephrata Community Hospital Geisinger Shamokin Area Community Hospital Carbon Lancaster General Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Gnaden Huetten UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury Campus Lancaster General Women & Babies Hospital Philadelphia St. -

Employee Handbook

Employee Handbook You and Jefferson Thomas Jefferson University & Hospitals Stephen K. Klasko, MD, MBA President and CEO Thomas Jefferson University and Jefferson Health System Dear Colleague, Welcome to Thomas Jefferson University and Hospitals! In accepting your new position, you have joined a team committed to redefining healthcare. With a robust history and community roots dating back to 1824, Jefferson is a nationally influential and widely respected academic medical center. We deliver high quality, personalized and compassionate care, and you are now a vital part of our tradition of excellence. By selecting Jefferson, you will enjoy competitive pay, a broad selection of employee benefits from which to choose, opportunity for educational and developmental growth, and a challenging and interactive work environment. Congratulations and my best wishes as you assume your new responsibilities at Jefferson. Sincerely, Stephen K. Klasko, MD, MBA President and CEO Thomas Jefferson University and Jefferson Health System About This Handbook This employee handbook has been designed to provide you with general information about various policies, benefits, services and facilities of Jefferson which may be of interest to you in the course of your employment. Please understand that it only highlights these topics. More specific information may be obtained from your supervisor, the hospital intranet, where any specific policies cited here may be found or the Department of Human Resources at Suite 2150 Gibbon Building or Methodist Administration Suite. You are strongly encouraged to become acquainted with all Jefferson policies and procedures to make your employment as satisfying and productive as possible. The policies, procedures and benefits described in this handbook are not all-inclusive and may be amended or rescinded from time to time at the discretion of Jefferson, with or without notice. -

Restructuring the MLH/Jefferson Partnership

Main Line Health Physician Restructuring the MLH/Jefferson partnership Surviving Sepsis: The future of Hepatology: SUMMER 2014 ED success moves health care at From Hep C to Inside: to inpatient Exton Square Mall transplant care Main Line Health Physician Medical staff education initiative BY ANGUS GILLIS, MD The Main Line Health medical staff structure is an integrated model that encompasses private practice MESSAGES | 2 physicians who are on staff, hospital-employed physicians, and physicians/physician groups who are under contract for provision of services to the Hospital System. Medical staff functions have traditionally included initial credentialing, reappointment, and approval of privileges for new procedures. Tools used to fulfill these tasks include focused and ongoing professional practice evaluation (FPPE and OPPE). The staff is responsible for peer review, including case study and quality concerns. By-law and policy issues such as investigations, interventions, confidentiality, and physician rights are also areas in which the medical staff is involved. The staff has administrative functions related to patient safety, infection control, pharmacy and therapeutics, medical records, and behavioral issues like disruptive behavior and practitioner health. This is only a partial list of the responsibilities of the medical staff. Ultimate responsibility for approval and implementation of any recommendations by the staff’s Medical Executive Committee lies with the Board of Main Line Health. In addition to the above functions, the medical staff also takes an active role in continuing medical education. Your medical staff dues have always funded clinical educational efforts, such as Grand Rounds, at our various locations. A new additional effort is the Medical Executive Committee’s budgeting of dedicated monies for physician education, which will enable members to carry out these medical staff responsibilities. -

Designated Acute Care Hospital Stroke Centers 180424

Acute Stroke -ready; Comprehensive stroke COUNTY FACILITY NAME CITY ZIP Center or Primary Stroke Center? MONTGOMERY Abington Memorial Hospital Comprehensive stroke Center Abington 19001 ALLEGHENY Allegheny General Hospital Comprehensive Stroke Center Pittsburgh 15212 CUMBERLAND Carlisle Regional Medical Center Primary Stroke Center Carlisle 17015 FRANKLIN Chambersburg Hospital Primary Stroke Center Chambersburg 17201 CHESTER Chester County Hospital – Chester County Primary Stroke Center West Chester 19380 CAMBRIA Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Primary Stroke Center Johnstown 15905 BLAIR Conemaugh Nason Medical Center Acute Stroke -ready Roaring Spring 16673 BUCKS Doylestown Hospital Primary Stroke Center Doylestown 18901 MONTGOMERY Einstein Medical Center Montgomery Primary Stroke Center East Norriton 19403 LANCASTER Ephrata Community Hospital Primary Stroke Center Ephrata 17522 WESTMORELAND Excela Health Frick Hospital Primary Stroke Center Westmoreland 15666 WESTMORELAND Excela Health Latrobe Hospital Primary Stroke Center Latrobe 15650 WESTMORELAND Excela Health Westmoreland Hospital Primary Stroke Center Greensburg 15601 LACKAWANNA Geisinger Community Medical Center – Scranton - Lackawanna County Primary Stroke Center Scranton 18510 MONTOUR Geisinger Medical Center – Montour County Primary Stroke Center Danville 17822 LUZERNE Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center, Wilkes-Barre – Luzerne County Primary Stroke Center Wilkes Barre 18711 ADAMS Gettysburg Hospital Primary Stroke Center Gettysburg 17325 CARBON Gnadden Huetten Memorial -

HMO Proactive Tiered Network Hospital List

Save with Keystone HMO Proactive, our most popular plans Keystone HMO Proactive health plans are our most popular for good reason: You get access to high-quality care and save money. Not only do you pay less for your monthly premiums, but you can save even more by choosing doctors and hospitals in Tier 1 – Preferred. Save with Tier 1 – Preferred Tier 1 – Preferred includes more than 50 percent of the network. Keystone HMO Proactive offers the same essential health benefits as our other health plans, including doctor visits, Tier 1 – Preferred hospital stays, prescription drug coverage, blood tests, and X-rays. The difference is its tiered provider network, which gives you the option to pay less for care by choosing Tier 1 –Preferred providers. Here are the most important things to know about Keystone HMO Proactive: • You can visit any doctor or hospital in the Independence Blue Cross network once you have a referral. Tier 2 – Enhanced Tier 3 – Standard • You will select a PCP to coordinate your care and refer you to specialists. • Some services cost the same no matter what provider you Save even more choose — like preventive care, emergency room visits, and Keystone HMO Silver Proactive Select and Keystone HMO Silver urgent care. Proactive Value: These lower-premium options are only available • When you use doctors and hospitals in Tier 1 – Preferred, when you purchase directly from Independence Blue Cross. you pay the lowest out-of-pocket costs. Keystone HMO Silver Proactive Value includes a deductible for • The choice is always yours. You can choose Tier 1 providers Tiers 1 – 3 for some services. -

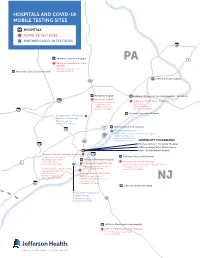

COVID Testing Sites

HOSPITALS AND COVID-19 MOBILE TESTING SITES HOSPITALS COVID-19 TEST SITES PARTNER COVID-19 TEST SITES 95 Abington–Lansdale Hospital PA 1 Abington–Lansdale Hospital PAT Site 100 Medical Campus Drive Physicians Care Surgical Hospital Lansdale, PA 19446 Jeerson Bucks Hospital 611 Abington Hospital Rothman Orthopedic Specialty Hospital – Bensalem Abington Hospital 276 Jeerson Urgent Care – Bensalem (Corner of Horace and Highland Avenues) (Parking lot) 1200 Old York Road 2966 Street Road Bensalem, PA 19020 76 Abington, PA 19001 Jeerson Torresdale Hospital St. Raymond’s of Penefort Church in Mount Airy 7940 Williams Ave. Philadelphia, PA 19150 1 Jeerson Frankford Hospital 76 Ampersand (City Life) (at the Jeerson Northeast Frankford campus) 95 5000 Frankford Avenue Medical Oce Building 611 Philadelphia, PA 19124 CENTER CITY PHILADELPHIA 476 Thomas Jeerson University Hospital Jeerson Hospital for Neuroscience Magee Rehabilitation Hospital Thomas Jeerson University Hospital 676 (Located at the Emergency Jeerson Cherry Hill Hospital Department entry ramp) Jeerson Methodist Hospital 132. S 10th Street Jeerson Cherry Hill Hospital 1 Methodist Hospital PAT Site Philadelphia, PA 19107 (Rear of hospital, near Behavioral Health entrance) 2301 S. Broad Street, 2nd Floor 2201 Chapel Avenue West For Pre-surgical or Pre-procedural Philadelphia, PA 19148 Cherry Hill, NJ 08002 (asymptomatic) patients: 925 Chestnut St. Jeerson Health – Navy Yard 4th Floor, Patient Testing (Entrance to garage site o Philadelphia, PA 19107 13th Street and Intrepid Avenue) NJ 3 Crescent Drive 95 Philadelphia, PA 19112 Jeerson Stratford Hospital Richard Allen Preparatory Charter School 5701 Lindbergh Blvd. 42 Philadelphia, PA 19143 DE 95 Jeerson Washington Twp Hospital Jeerson Washington Twp Hospital 367 Hurfville-Cross Keys Road Sewell, NJ 08080 PLEASE NOTE: Physician referral is required for testing at these sites. -

Residency Match List 2021

PHILADELPHIA COLLEGE OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE 2021 Residency List – Philadelphia Campus Anesthesiology (8) Family Medicine (con’t) Cook County Health and Hosp Sys, IL Jefferson Health - Northeast, PA (2) Hospital of the Univ of Pennsylvania, PA Lankenau Medical Center, PA Indiana University SOM, IN McLaren Health Care, MI Penn State Hershey Medical Center, PA Mike O'Callaghan Federal Hospital, Tower Health/Reading Hospital, PA (2) Nellis Air Force Base/Univ of Nevada UCLA Medical Center, CA School of Medicine, NV (2)* UPMC Pinnacle Hospitals, PA Naval Hospital Jacksonville, FL* NCC - Fort Belvoir Community Hosp, VA* Emergency Medicine (28) Northwestern McGaw Lake Forest, IL Albert Einstein Medical Center, PA (2) OhioHealth-Doctors Hospital, OH Capital Health Regional Medical Center, NJ OhioHealth-Grant Medical Center, OH Christiana Care, DE Penn Medicine-Lancaster General Hosp, PA CMSRU/Cooper University Hospital, NJ Penn State Hershey Medical Center, PA Crozer-Chester Medical Center, PA (3) Puyallup Tribal Health Authority, WA Florida Atlantic University Rowan University SOM, NJ (2) -Charles E. Schmidt COM, FL Rutgers-RWJUH Somerset, NJ Geisinger Health System, PA St. Lukes Hospital, PA Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, CA St. Lukes Hospital-Anderson, PA (2) HCA Healthcare/USF Morsani GME Suburban Community Hospital, PA -Oak Hill, FL Univ of Massachusetts Med School, MA Inspira Health Network, NJ (2) UPMC McKeesport, PA Jefferson Health - Northeast, PA (2) UPMC Presbyterian Shadyside, PA Jefferson Health NJ - Rowan SOM, NJ (2) UPMC Williamsport, -

PA Ehealth Partnership P3N ADT Operations Facilities in Production Exchange ER Name Type of Facility Subtype - ED, Inpatient, Etc

PA eHealth Partnership P3N ADT Operations Facilities in Production Exchange ER Name Type of Facility Subtype - ED, Inpatient, etc. Consent Model Address HSX Mainline Health Bryn Mawr Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 130 South Bryn Mawr Avenue, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010 HSX Mainline Health Lankenau Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 100 Lancaster Avenue, Wynnewood, PA 19096 HSX Mainline Health Paoli Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 255 W. Lancaster Avenue, Paoli, PA 19301 HSX Mainline Health Riddle Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 1068 West Baltimore Pike, Media, PA 19063 HSX Temple University Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 3401 N.Broad Street,Philadelphia, PA 19140 HSX Temple Jeanes Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 7600 Central Avenue, Philadelphia,PA 19111 HSX Crozer-Chester Medical Center hospital ED Opt out 1 Medical Center Blvd, Chester, PA 19013 HSX Crozer Delaware County Memorial Hospital hospital ED Opt out 501 N Lansdowne Ave, Drexel Hill, PA 19026 HSX Crozer Springfield Hospital hospital ED Opt out 190 W Sproul Rd, Springfield, PA 19064 HSX Crozer Taylor Hospital hospital ED Opt out 175 E Chester Pike, Ridley Park, PA 19078 HSX Doylestown Hospital hospital ED,INPATIENT Opt out 595 West State Street, Doylestown, PA 18901 HSX Einstein Medical Center Elkins Park hospital ED,INPATIENT Opt out 60 Township Line Rd, Elkins Park, PA 19027 HSX Einstein Medical Center Montgomery hospital ED,INPATIENT Opt out 559 W Germantown Pike, East Norriton, PA 19403 HSX Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia hospital ED,INPATIENT Opt out 5501 Old York Rd, Philadelphia, PA 19141 HSX Holy Redeemer Hospital hospital ED,INPATIENT Opt Out 1648 Huntingdon Pike, Meadowbrook, PA 19046 HSX Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 1500 Lansdowne Avenue, Darby, PA 19023 HSX Mercy Nazareth Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 2601 Holme Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19152 HSX Mercy Philadelphia Hospital hospital ED Opt Out 501 South 54th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19143 HSX St. -

Community 2019

Southeastern Pennsylvania Community 2019 SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT Partnering Hospitals • Abington Hospital • Abington Lansdale Hospital • Chester County Hospital • Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia • Einstein Medical Center Montgomery NEEDS ASSESSMENT HEALTH COMMUNITY • Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia • Einstein Medical Center Elkins Park • Grand View Hospital • Holy Redeemer Hospital • Jefferson Bucks Hospital • Jefferson Frankford Hospital • Jefferson Torresdale Hospital • Thomas Jefferson University Hospital • Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience • Jefferson Methodist Hospital • Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania • Pennsylvania Hospital • Penn Presbyterian Medical Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................2 Philadelphia County, PA ..................................127 1. Center City .........................................................128 Partners ....................................................13 2. Far North Philadelphia ......................................130 1. Introduction .......................................................13 3. Far Northeast Philadelphia ...............................134 2. Participating Hospitals and Health Systems ....14 4. Lower Northeast Philadelphia ...........................138 a. Hospital Profiles 5. North Philadelphia – East .................................142 i. Overview of Hospital 6. North Philadelphia – West ................................146 ii. Past CHNA and Community 7. Northwest -

Learn More About the Jefferson Enterprise

JULY 2021 WE ARE 34,500+ PEOPLE REIMAGINING HEALTH CARE, EDUCATION AND DISCOVERY. WE ARE MANY THINGS, BUT EVERY DAY ALL OF US ARE DEDICATED TO ONE THING: IMPROVING LIVES. WE ARE JEFFERSON WE ARE • Philadelphia’s second largest employer* • Thomas Jefferson University is ranked among the top national doctoral universities by U.S. News & World • Nationally ranked by U.S.News & World Report Report, and in a variety of specialty areas including in nine specialties, including #2 in ophthalmology social mobility, engineering and colleges for veterans. (Wills Eye) and #16 in rehabilitation (Magee Rehabilitation Hospital); ranked second best • The University consists of 10 colleges and 4 schools hospital in the Philadelphia Metro area with programs in architecture, business, design, engineering, fashion and textiles, health, medicine • Jefferson Health includes 14 hospitals, 2,851 and social science licensed beds, 3,700 physicians and practitioners and 7,200 nurses • More than 160 undergraduate/graduate programs • 40+ outpatient and urgent care locations and • Fashion programs are ranked among the best in 3.8 million outpatient visits the world by Fashionista, Business of Fashion and CEOWORLD Magazine. • NCI-designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center – one of only two nationally ranked cancer centers in the greater Philadelphia region *ranked by number of local employees Jefferson.edu | JeffersonHealth.org Reimagine is our commitment to raising the resources it takes to change the world, not in a small way or a single way, but in multiple, meaningful ways— swiftly and simultaneously. By focusing on four key themes, we’re going to change the future for Philadelphia and beyond: People Leading Optimistic Revolutions Spaces that Heal and Inspire Communities United for Health Equity Discoveries that Improve Lives This is your chance to make a difference. -

Nursing Annual Report – 2018-2019

BEYOND THE STETHOSCOPE Nursing Annual Report 2018-2019 Jefferson Bucks Hospital Jefferson Frankford Hospital Jefferson Torresdale Hospital A MESSAGE FROM MICHELLE I am so pleased to present you with this year’s Nursing Annual Report. I hope you will take some time to look it over and share in the many accomplishments of the department. When I think back on all we have achieved in this past year, I feel incredibly proud of each of you and the work you do every day. It never escapes me how difficult your work can be and, at the same time, what a profound effect you each have on the lives of those for whom you care. The members of our community look to us as trusted professionals to guide and support them with skill, compassion, and caring through some of the most profound moments of their lives. I hear from grateful patients and their families who describe to me how each of you uniquely creates an atmosphere of caring through your skill, your advocacy, and your compassion. Nursing excellence occurs at the crossroads between each individual nurse and her/his patient. You demonstrate that excellence through every interaction you have with your patients and every relationship you have with one another. Know that I am always grateful for each one of you, and both proud and inspired by the wonderful work you do. I thank you for allowing me to be a part of this phenomenal Jefferson Health — Northeast nursing team. MICHELLE CONLEY, DNP, MBA, BSN, RN Senior Vice President & Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) Jefferson Health — Northeast A NOTE FROM OUR NURSING LEADERS Jefferson Health – Northeast is proud of the exceptional care professional nursing, clinical policy development, informatics, that is provided to our patients, as well as their families, every day.