City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Interview Class Act

Sheena Grant interview Class act Her music is as breathtakingly beautiful as the images it was written to accompany. Sheena Grant finds out what inspires composer Sarah Class usician and “It’s one of the most singularly composer Sarah powerful and effective charities that Class is a woman I’ve been fortunate enough to in demand. experience,” she says. “I got involved At only 34 years because I was looking for a way to old she is already help the environment through my one of Britain’s music and the WLT seemed to be a most sought-after quietly powerful and effective charity musical talents, whose making huge headway into protecting Mhauntingly beautiful and natural habitats. evocative compositions have “My three biggest loves are people, helped bring to life many of the nature and music - in no particular nation’s favourite natural order - and through music I hope to do history documentaries over the something to help the other two. The last decade or so. more you highlight animals and the She may not yet be a household problems in our world the more name but many of the landmark beauty you show people, who might series for which she has provided the go on to feel the importance of music are, including the David protecting these habitats. Attenborough-fronted Africa, “The evening in Halesworth is part Madagascar and the State of the of that. It will feature music, film Planet. sequence and I will do a kind of Sarah is about to make her first trip question and answer with Bill Oddie, to Suffolk. -

Beyond Planet Earth: the Future of Planet Earth: Beyond 20 22 18 14 12 6 8 4 ; and the of 35Th the Anniversary 3

Member Magazine Fall 2011 Vol. 36 No. 4 Searching For Life on Mars How to Opening Build November 19 a Lunar BEYOND Elevator PLANET EARTH: THE FUTURE OF SPACE EXPLORATION Astrophysics at the Museum 2 News at the Museum 3 From the Even for those of us long past our school years, fall of you participated. Based on that work, the Museum More Stars Shine Brighter With Museum To Offer always feels like “back to school”—a time for new has restructured and enhanced its program to bring President ventures and new adventures. The most exciting it more fully in line with Members’ lives. Hayden Planetarium Upgrade Science Teaching Degree new venture at the Museum is our Master of Arts Membership categories will now more closely Ellen V. Futter in Teaching (MAT) program, which marks the first reflect the kinds of households that you are part This fall, the Museum is launching a Master time that an institution other than a university of, with new Family and Adult tracks that will of Arts in Teaching (MAT) program, marking or college will offer a master’s program for science allow us to tailor programs, services, and benefits. the first time that an institution other than teachers. Please read more about this pioneering And, moving forward, there will be an increased a university or college will offer such a program initiative on page 3. emphasis on communication, including keeping for science teachers. Fall 2011 brings a full slate of exciting offerings in closer touch with Members through electronic The pioneering 15-month program is for the public, including our thrilling new means, including a new digital membership. -

A World of Quarterly Newsletter

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Where have all the beaches gone? p. 12 Natural Sciences A World of Quarterly Newsletter Vol. 1, No. 1 October–December 2002 CONTENTS EDITORIAL SUMMIT NEWS 2 UNESCO and Johannesburg ‘Our house is burning’ World of Science is being launched as part of the new communication strategy of OTHER NEWS A the Sector of Natural Sciences of UNESCO. The aim of this quarterly newsletter 6 Member States celebrate first is to keep UNESCO’s concerns in the public eye and at the centre of public debate by World Science Day making information easily available and attractive reading. It is my hope that this will 7 Door opens for SESAME provide a new service for all those who follow with interest developments in UNESCO’s science programmes. 8 CUBES seals partnership between UNESCO and Other innovations in communication include the UNESCO science portal 1 and more Columbia University specific portals, such as those on water 2 and oceans 3. 9 Steep increase for women in science prize money Besides being available on the web, A World of Science is being despatched to 9 A strong voice for small islands depository libraries around the world, to government ministries, to the 188 National Commissions for UNESCO and to UNESCO’s partners in the intergovernmental and 9 UNESCO Chair launched non-governmental communities. in sciences This first issue of A World of Science is published in the wake of the World Summit INTERVIEW on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg, South Africa, from 26 August to 4 September. -

Netflix Cheat Sheet

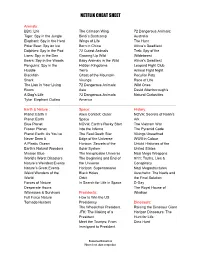

NETFLIX CHEAT SHEET Animals: BBC: Life The Crimson Wing 72 Dangerous Animals: Tiger: Spy in the Jungle Bindi’s Bootcamp Australia Elephant: Spy in the Herd Wings of Life The Hunt Polar Bear: Spy on Ice Born in China Africa’s Deadliest Dolphins: Spy in the Pod 72 Cutest Animals Trek: Spy of the Lions: Spy in the Den Growing Up Wild Wildebeest Bears: Spy in the Woods Baby Animals in the Wild Africa’s Deadliest Penguins: Spy in the Hidden Kingdoms Leopard Fight Club Huddle Terra Animal Fight Night Blackfish Ghost of the Mountain Peculiar Pets Shark Virunga Race of LIfe The Lion in Your Living 72 Dangerous Animals: Wild Ones Room Asia David Attenborough’s A Dog’s Life 72 Dangerous Animals: Natural Curiosities Tyke: Elephant Outlaw America Earth & Nature : Space: History: Planet Earth II Alien Contact: Outer NOVA: Secrets of Noah’s Planet Earth Space Ark Blue Planet NOVA: Earth’s Rocky Start The Vietnam War Frozen Planet Into the Inferno The Pyramid Code Planet Earth: As You’ve The Real Death Star Vikings Unearthed Never Seen It Edge of the Universe WWII in Colour A Plastic Ocean Horizon: Secrets of the Untold Histories of the Earth’s Natural Wonders Solar System United States Mission Blue The Inexplicable Universe Nazi Mega Weapons World’s Worst Disasters The Beginning and End of 9/11: Truths, Lies & Nature’s Weirdest Events the Universe Conspiracy Nature’s Great Events Horizon: Supermassive Nazi Megastructures Weird Wonders of the Black Holes Auschwitz: The Nazis and World Orbit the Final Solution Forces of Nature In Search for Life in Space D-Day Desperate Hours: The Royal House of Witnesses & Survivors Presidents: Windsor Full Force Nature How to Win the US Tornado Hunters Presidency Dinosaurs: The Wheelchair President Raising the Dinosaur Giant JFK: The Making of a Horizon Dinosaurs: The President Hunt for Life Meet the Trumps: From Dino Hunt Immigrant to President HomeschoolHideout.com Please do not share or reproduce. -

Greening Wildlife Documentary’, in Libby Lester and Brett Hutchins (Eds) Environmental Conflict and the Media, New York: Peter Lang

Morgan Richards (forthcoming 2013) ‘Greening Wildlife Documentary’, in Libby Lester and Brett Hutchins (eds) Environmental Conflict and the Media, New York: Peter Lang. GREENING WILDLIFE DOCUMENTARY Morgan Richards The loss of wilderness is a truth so sad, so overwhelming that, to reflect reality, it would need to be the subject of every wildlife film. That, of course, would be neither entertaining nor ultimately dramatic. So it seems that as filmmakers we are doomed either to fail our audience or fail our cause. — Stephen Mills (1997) Five years before the BBC’s Frozen Planet was first broadcast in 2011, Sir David Attenborough publically announced his belief in human-induced global warming. “My message is that the world is warming, and that it’s our fault,” he declared on the BBC’s Ten O’Clock News in May 2006. This was the first statement, both in the media and in his numerous wildlife series, in which he didn’t hedge his opinion, choosing to focus on slowly accruing scientific data rather than ruling definitively on the causes and likely environmental impacts of climate change. Frozen Planet, a seven-part landmark documentary series, produced by the BBC Natural History Unit and largely co-financed by the Discovery Channel, was heralded by many as Attenborough’s definitive take on climate change. It followed a string of big budget, multipart wildlife documentaries, known in the industry as landmarks1, which broke with convention to incorporate narratives on complex environmental issues such as habitat destruction, species extinction and atmospheric pollution. David Attenborough’s The State of the Planet (2000), a smaller three-part series, was the first wildlife documentary to deal comprehensively with environmental issues on a global scale. -

Psychology of Space Exploration Psychology of About the Book Douglas A

About the Editor Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective Psychology of Space Exploration Psychology of About the Book Douglas A. Vakoch is a professor in the Department As we stand poised on the verge of a new era of of Clinical Psychology at the California Institute of spaceflight, we must rethink every element, including Integral Studies, as well as the director of Interstellar Space Exploration the human dimension. This book explores some of the Message Composition at the SETI Institute. Dr. Vakoch Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective contributions of psychology to yesterday’s great space is a licensed psychologist in the state of California, and Edited by Douglas A. Vakoch race, today’s orbiter and International Space Station mis- his psychological research, clinical, and teaching interests sions, and tomorrow’s journeys beyond Earth’s orbit. include topics in psychotherapy, ecopsychology, and meth- Early missions into space were typically brief, and crews odologies of psychological research. As a corresponding were small, often drawn from a single nation. As an member of the International Academy of Astronautics, intensely competitive space race has given way to inter- Dr. Vakoch chairs that organization’s Study Groups on national cooperation over the decades, the challenges of Interstellar Message Construction and Active SETI. communicating across cultural boundaries and dealing Through his membership in the International Institute with interpersonal conflicts have become increasingly of Space Law, he examines -

Frank White and Charles E

1 Special thanks to the ICF for being a Premium Sponsor We’d love to have your support! Become a sponsor here: https://libraryofprofessionalcoaching.com/sponsor/ Become a benefactor or patron here: https://libraryofprofessionalcoaching.com/patron/ A listing of logos for all of our very generous and supportive sponsors is to be found at the end of Curated 2018. 2 CURATED 2018 EDITORS Suzi Pomerantz Suzi Pomerantz, CEO of Innovative Leadership International, LLC is an award- winning executive coach and #1 bestselling author with 25 years experience coaching leaders and teams in 200+ organizations. Suzi specializes in leadership influence, helping executives and organizations find clarity in chaos. She was among the first awarded the Master credential from the ICF 20 years ago and is a thought leader serving on several Boards. Suzi designed the LEAP Tiered Coaching Program for leadership teams, founded the Leading Coaches’ Center and co-founded the Library of Professional Coaching. http://www.InnovativeLeader.com 3 William Bergquist An international coach and consultant, professor in the fields of psychology, management and public administration, author of more than 45 books, and president of a graduate school of psychology. Dr. Bergquist consults on and writes about personal, group, organizational and societal transitions and transformations. In recent years, Bergquist has focused on the processes of organizational coaching. He is co-founder of the International Journal of Coaching in Organizations, the Library of Professional Coaching and the International Consortium for Coaching in Organizations. His graduate school (The Professional School of Psychology) offers Master and Doctoral degrees to mature, accomplished adults in both clinical and organizational psychology. -

The Overview Effect and the Ultraview Effect: How Extreme Experiences In/Of Outer Space Influence Religious Beliefs in Astronaut

religions Article The Overview Effect and the Ultraview Effect: How Extreme Experiences in/of Outer Space Influence Religious Beliefs in Astronauts Deana L. Weibel Anthropology Department, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 11 August 2020; Published: 13 August 2020 Abstract: This paper, based mainly on astronauts’ first-person writings, historical documents, and my own ethnographic interviews with nine astronauts conducted between 2004 and 2020, explores how encountering the earth and other celestial objects in ways never before experienced by human beings has influenced some astronauts’ cosmological understandings. Following the work of Timothy Morton, the earth and other heavenly bodies can be understood as “hyperobjects”, entities that are distributed across time and space in ways that make them difficult for human beings to accurately understand, but whose existence is becoming increasingly detectable to us. Astronauts in outer space are able to perceive celestial objects from vantages literally unavailable on earth, which has often (but not always) had a profound influence on their understandings of humanity, life, and the universe itself. Frank Wright’s term, the “overview effect”, describes a cognitive shift resulting from seeing the Earth from space that increases some astronauts’ sense of connection to humanity, God, or other powerful forces. Following NASA convention (NASA Style Guide, 2012), I will capitalize both Earth and Moon, but will leave all quotations in their original style. The “ultraview effect” is a term I introduce here to describe the parallel experience of viewing the Milky Way galaxy from the Moon’s orbit (a view described reverently by one respondent as a “something I was not ready for”) that can result in strong convictions about the prevalence of life in the universe or even unorthodox beliefs about the origins of humanity. -

Saving Planet Earth by Jack Spencer Fountas-Pinnell Level S Science Fiction Selection Summary in the Year 3030 Only a Few Humans Live on Planet Earth

LESSON 4 TEACHER’S GUIDE Saving Planet Earth by Jack Spencer Fountas-Pinnell Level S Science Fiction Selection Summary In the year 3030 only a few humans live on planet Earth. Derek is a scientist stationed on planet Earth. He tries to fi nd signs of life to save the planet. His son Dennis discovers butterfl ies. His discovery saves planet Earth. Number of Words: 1,603 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Science fi ction Text Structure • Third-person narrative with detailed episodes • Includes a prologue to give background information Content • Environmental disaster • Importance of air, plants, and insects to Earth • Scientifi c research Themes and Ideas • It is important to preserve history. • Scientifi c discoveries help the earth in many ways. • Persistence leads to success. Language and • Long stretches of descriptive language important to understanding the setting and the Literary Features characters of the story. • Multiple characters revealed by what they say, think, and do as well as what other characters say and think about them • Setting is distant in time and space from students’ experiences Sentence Complexity • Longer complex sentence structures that include dialogue as well as embedded clauses and phrases • Questions in dialogue Vocabulary • Vocabulary words that readers must derive from context: monitor, wrist communicator, void Words • Many multisyllable words: permanently, stubbornly, possibility Illustrations • Colorful illustrations with captions support the text. Book and Print Features • Easy-to-read chapter headings • Captions under illustrations provide important information for understanding the story © 2006. Fountas, I.C. & Pinnell, G.S. Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Heinemann, Portsmouth, N.H. Copyright © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company All rights reserved. -

The State of the Planet's Wildlife

The State of the Planet’s Wildlife Introduction There’s a place in the world where a lush rainforest — with open meadows, bamboo thickets and fresh running streams — provides a safe haven for a group of endangered lowland gorillas. In this jungle sanctuary highly threatened animals survive without fear of being stalked by local poachers. It's a place where the affects of Africa’s extreme poverty and civil unrest seem a world away. But what really makes this patch of wilderness so extraordinary is the fact that that it's not located in a remote part of Africa. It’s in New York City. The Wildlife Conservation Society’s Bronx Zoo gorilla exhibit is one of the city’s most popular attractions, providing visitors with a rare and intimate glimpse of the natural world. However realistic the experience seems to be, much of the food the gorillas eat comes from local markets, most of the trees are made of metal and epoxy, and the forest that lies behind these thick walls of protective glass is essentially an environmental illusion. But what is not an illusion is the fact that the zoos of the future may have no choice but become urban sanctuaries for our planet’s animals. Scientists now tell us that as much as a half of the world’s wildlife may completely disappear during our lifetime. “Every kind of species, every broad type of species, every broad type of habitat is under threat now in a way that wasn’t true in all of past human history.” — Robert Engelman, Population Action International Once, not so very long ago, the Earth was a place of great and unspoiled diversity, a rich tapestry dominated by the elegance of the natural world. -

New York State Conservationist OCTOBER 2018 the Deer Camp As We Know It Today Evolved Steadily in the Post- WWII Era

OCTOBER 2018 Are New York’s fall colors at risk? Hunting | Artifi cial ReefS | Whales Humpback whale breaching Humpback whale breaching Volume 73, Number 2 | October 2018 Dear Reader, Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor of New York State Outdoor traditions like hunting, hiking and fi shing DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION have defi ned our state for many generations, yet, as Basil Seggos, Commissioner Sean Mahar, Asst. Commissioner for Public Affairs most of you are aware, our natural resources and Harold Evans, Director of Office of Communication Services way of life are being threatened by climate change. THE CONSERVATIONIST STAFF In this issue we take a look at the impacts on some of Eileen C. Stegemann, Editor Peter Constantakes, Assistant Editor New York’s key species and habitats from our forests Megan Ciotti, Business Manager Jeremy J. Taylor, Conservationist for Kids to our marine waters (see pg. 6). DEC is tackling Ellen Bidell, Contributing Editor this problem on many fronts, including responding DESIGN TEAM to destructive storms like Superstorm Sandy and Andy Breedlove, Photographer/Designer Jim Clayton, Chief, Multimedia Services damaging fl ooding like we recently saw in the Finger Lakes region (see Mark Kerwin, Graphic Designer pg. 19). Our goal is to preserve vital natural resources and wildlife habitats, Robin-Lucie Kuiper, Photographer/Designer Mary Elizabeth Maguire, Graphic Designer protect people from the impacts of a warming climate, and preserve the Jennifer Peyser, Graphic Designer quality of life we enjoy in New York. I encourage you be an active partner in Maria VanWie, Graphic Designer the crucial e ort. EDITORIAL OFFICES The Conservationist (ISSN0010-650X), © 2018 by NYSDEC, Fall heralds the exciting return of deer and bear hunting seasons, is an official publication of the New York State Department New York has a long and proud hunting tradition, which is captured in of Environmental Conservation published bimonthly at 625 Broadway, 4th Floor, Albany, NY 12233-4502.