6. the Lebesgue Measure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set Theory, Including the Axiom of Choice) Plus the Negation of CH

ANNALS OF ~,IATltEMATICAL LOGIC - Volume 2, No. 2 (1970) pp. 143--178 INTERNAL COHEN EXTENSIONS D.A.MARTIN and R.M.SOLOVAY ;Tte RockeJ~'ller University and University (.~t CatiJbrnia. Berkeley Received 2 l)ecemt)er 1969 Introduction Cohen [ !, 2] has shown that tile continuum hypothesis (CH) cannot be proved in Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory. Levy and Solovay [9] have subsequently shown that CH cannot be proved even if one assumes the existence of a measurable cardinal. Their argument in tact shows that no large cardinal axiom of the kind present;y being considered by set theorists can yield a proof of CH (or of its negation, of course). Indeed, many set theorists - including the authors - suspect that C1t is false. But if we reject CH we admit Gurselves to be in a state of ignorance about a great many questions which CH resolves. While CH is a power- full assertion, its negation is in many ways quite weak. Sierpinski [ 1 5 ] deduces propcsitions there called C l - C82 from CH. We know of none of these propositions which is decided by the negation of CH and only one of them (C78) which is decided if one assumes in addition that a measurable cardinal exists. Among the many simple questions easily decided by CH and which cannot be decided in ZF (Zerme!o-Fraenkel set theory, including the axiom of choice) plus the negation of CH are tile following: Is every set of real numbers of cardinality less than tha't of the continuum of Lebesgue measure zero'? Is 2 ~0 < 2 ~ 1 ? Is there a non-trivial measure defined on all sets of real numbers? CIhis third question could be decided in ZF + not CH only in the unlikely event t Tile second author received support from a Sloan Foundation fellowship and tile National Science Foundation Grant (GP-8746). -

Geometric Integration Theory Contents

Steven G. Krantz Harold R. Parks Geometric Integration Theory Contents Preface v 1 Basics 1 1.1 Smooth Functions . 1 1.2Measures.............................. 6 1.2.1 Lebesgue Measure . 11 1.3Integration............................. 14 1.3.1 Measurable Functions . 14 1.3.2 The Integral . 17 1.3.3 Lebesgue Spaces . 23 1.3.4 Product Measures and the Fubini–Tonelli Theorem . 25 1.4 The Exterior Algebra . 27 1.5 The Hausdorff Distance and Steiner Symmetrization . 30 1.6 Borel and Suslin Sets . 41 2 Carath´eodory’s Construction and Lower-Dimensional Mea- sures 53 2.1 The Basic Definition . 53 2.1.1 Hausdorff Measure and Spherical Measure . 55 2.1.2 A Measure Based on Parallelepipeds . 57 2.1.3 Projections and Convexity . 57 2.1.4 Other Geometric Measures . 59 2.1.5 Summary . 61 2.2 The Densities of a Measure . 64 2.3 A One-Dimensional Example . 66 2.4 Carath´eodory’s Construction and Mappings . 67 2.5 The Concept of Hausdorff Dimension . 70 2.6 Some Cantor Set Examples . 73 i ii CONTENTS 2.6.1 Basic Examples . 73 2.6.2 Some Generalized Cantor Sets . 76 2.6.3 Cantor Sets in Higher Dimensions . 78 3 Invariant Measures and the Construction of Haar Measure 81 3.1 The Fundamental Theorem . 82 3.2 Haar Measure for the Orthogonal Group and the Grassmanian 90 3.2.1 Remarks on the Manifold Structure of G(N,M).... 94 4 Covering Theorems and the Differentiation of Integrals 97 4.1 Wiener’s Covering Lemma and its Variants . -

Shape Analysis, Lebesgue Integration and Absolute Continuity Connections

NISTIR 8217 Shape Analysis, Lebesgue Integration and Absolute Continuity Connections Javier Bernal This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8217 NISTIR 8217 Shape Analysis, Lebesgue Integration and Absolute Continuity Connections Javier Bernal Applied and Computational Mathematics Division Information Technology Laboratory This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8217 July 2018 INCLUDES UPDATES AS OF 07-18-2018; SEE APPENDIX U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Walter Copan, NIST Director and Undersecretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ This Shape Analysis, Lebesgue Integration and publication Absolute Continuity Connections Javier Bernal is National Institute of Standards and Technology, available Gaithersburg, MD 20899, USA free of Abstract charge As shape analysis of the form presented in Srivastava and Klassen’s textbook “Functional and Shape Data Analysis” is intricately related to Lebesgue integration and absolute continuity, it is advantageous from: to have a good grasp of the latter two notions. Accordingly, in these notes we review basic concepts and results about Lebesgue integration https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8217 and absolute continuity. In particular, we review fundamental results connecting them to each other and to the kind of shape analysis, or more generally, functional data analysis presented in the aforeme- tioned textbook, in the process shedding light on important aspects of all three notions. Many well-known results, especially most results about Lebesgue integration and some results about absolute conti- nuity, are presented without proofs. -

Hausdorff Measure

Hausdorff Measure Jimmy Briggs and Tim Tyree December 3, 2016 1 1 Introduction In this report, we explore the the measurement of arbitrary subsets of the metric space (X; ρ); a topological space X along with its distance function ρ. We introduce Hausdorff Measure as a natural way of assigning sizes to these sets, especially those of smaller \dimension" than X: After an exploration of the salient properties of Hausdorff Measure, we proceed to a definition of Hausdorff dimension, a separate idea of size that allows us a more robust comparison between rough subsets of X. Many of the theorems in this report will be summarized in a proof sketch or shown by visual example. For a more rigorous treatment of the same material, we redirect the reader to Gerald B. Folland's Real Analysis: Modern techniques and their applications. Chapter 11 of the 1999 edition served as our primary reference. 2 Hausdorff Measure 2.1 Measuring low-dimensional subsets of X The need for Hausdorff Measure arises from the need to know the size of lower-dimensional subsets of a metric space. This idea is not as exotic as it may sound. In a high school Geometry course, we learn formulas for objects of various dimension embedded in R3: In Figure 1 we see the line segment, the circle, and the sphere, each with it's own idea of size. We call these length, area, and volume, respectively. Figure 1: low-dimensional subsets of R3: 2 4 3 2r πr 3 πr Note that while only volume measures something of the same dimension as the host space, R3; length, and area can still be of interest to us, especially 2 in applications. -

The Axiom of Choice and Its Implications

THE AXIOM OF CHOICE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS KEVIN BARNUM Abstract. In this paper we will look at the Axiom of Choice and some of the various implications it has. These implications include a number of equivalent statements, and also some less accepted ideas. The proofs discussed will give us an idea of why the Axiom of Choice is so powerful, but also so controversial. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. The Axiom of Choice and Its Equivalents 1 2.1. The Axiom of Choice and its Well-known Equivalents 1 2.2. Some Other Less Well-known Equivalents of the Axiom of Choice 3 3. Applications of the Axiom of Choice 5 3.1. Equivalence Between The Axiom of Choice and the Claim that Every Vector Space has a Basis 5 3.2. Some More Applications of the Axiom of Choice 6 4. Controversial Results 10 Acknowledgments 11 References 11 1. Introduction The Axiom of Choice states that for any family of nonempty disjoint sets, there exists a set that consists of exactly one element from each element of the family. It seems strange at first that such an innocuous sounding idea can be so powerful and controversial, but it certainly is both. To understand why, we will start by looking at some statements that are equivalent to the axiom of choice. Many of these equivalences are very useful, and we devote much time to one, namely, that every vector space has a basis. We go on from there to see a few more applications of the Axiom of Choice and its equivalents, and finish by looking at some of the reasons why the Axiom of Choice is so controversial. -

Caratheodory's Extension Theorem

Caratheodory’s extension theorem DBW August 3, 2016 These notes are meant as introductory notes on Caratheodory’s extension theorem. The presentation is not completely my own work; the presentation heavily relies on the pre- sentation of Noel Vaillant on http://www.probability.net/WEBcaratheodory.pdf. To make the line of arguments as clear as possible, the starting point is the notion of a ring on a topological space and not the notion of a semi-ring. 1 Elementary definitions and properties We fix a topological space Ω. The power set of Ω is denoted P(Ω) and consists of all subsets of Ω. Definition 1. A ring on on Ω is a subset R of P(Ω), such that (i) ∅ ∈ R (ii) A, B ∈ R ⇒ A ∪ B ∈ R (iii) A, B ∈ R ⇒ A \ B ∈ R Definition 2. A σ-algebra on Ω is a subset Σ of P(Ω) such that (i) ∅ ∈ Σ (ii) (An)n∈N ∈ Σ ⇒ ∪n An ∈ Σ (iii) A ∈ Σ ⇒ Ac ∈ Σ Since A∩B = A\(A\B) it follows that any ring on Ω is closed under finite intersections; c c hence any ring is also a semi-ring. Since ∩nAn = (∪nA ) it follows that any σ-algebra is closed under arbitrary intersections. And from A \ B = A ∩ Bc we deduce that any σ-algebra is also a ring. If (Ri)i∈I is a set of rings on Ω then it is clear that ∩I Ri is also a ring on Ω. Let S be any subset of P(Ω), then we call the intersection of all rings on Ω containing S the ring generated by S. -

(Measure Theory for Dummies) UWEE Technical Report Number UWEETR-2006-0008

A Measure Theory Tutorial (Measure Theory for Dummies) Maya R. Gupta {gupta}@ee.washington.edu Dept of EE, University of Washington Seattle WA, 98195-2500 UWEE Technical Report Number UWEETR-2006-0008 May 2006 Department of Electrical Engineering University of Washington Box 352500 Seattle, Washington 98195-2500 PHN: (206) 543-2150 FAX: (206) 543-3842 URL: http://www.ee.washington.edu A Measure Theory Tutorial (Measure Theory for Dummies) Maya R. Gupta {gupta}@ee.washington.edu Dept of EE, University of Washington Seattle WA, 98195-2500 University of Washington, Dept. of EE, UWEETR-2006-0008 May 2006 Abstract This tutorial is an informal introduction to measure theory for people who are interested in reading papers that use measure theory. The tutorial assumes one has had at least a year of college-level calculus, some graduate level exposure to random processes, and familiarity with terms like “closed” and “open.” The focus is on the terms and ideas relevant to applied probability and information theory. There are no proofs and no exercises. Measure theory is a bit like grammar, many people communicate clearly without worrying about all the details, but the details do exist and for good reasons. There are a number of great texts that do measure theory justice. This is not one of them. Rather this is a hack way to get the basic ideas down so you can read through research papers and follow what’s going on. Hopefully, you’ll get curious and excited enough about the details to check out some of the references for a deeper understanding. -

A Measure Blowup Sam Chow∗∗∗, Gus Schrader∗∗∗∗ and J.J

A measure blowup Sam Chow∗∗∗, Gus Schrader∗∗∗∗ and J.J. Koliha∗ ∗∗∗∗ Last year Sam Chow and Gus Schrader were third-year students at the Uni- versity of Melbourne enrolled in Linear Analysis, a subject involving — among other topics — Lebesgue measure and integration. This was based on parts of the recently published book Metrics, Norms and Integrals by the lecturer in the subject, Associate Professor Jerry Koliha. In addition to three lectures a week, the subject had a weekly practice class. The lecturer introduced an extra weekly practice class with a voluntary attendance, but most stu- dents chose to attend, showing a keen interest in the subject. The problems tackled in the extra practice class ranged from routine to very challenging. The present article arose in this environment, as Sam and Gus independently attacked one of the challenging problems. Working in the Euclidean space Rd we can characterise Lebesgue measure very simply by relying on the Euclidean volume of the so-called d-cells.Ad-cell C in Rd is the Cartesian product C = I1 ×···×Id of bounded nondegenerate one-dimensional intervals Ik; its Euclidean d-volume is d the product of the lengths of the Ik. Borel sets in R are the members of the least family Bd of subsets of Rd containing the empty set, ∅, and all d-cells which are closed under countable unions and complements in Rd. Since every open set in Rd can be expressed as the countable union of suitable d-cells, the open sets are Borel, as are all sets obtained from them by countable unions and intersections, and complements. -

RANDOMNESS – BEYOND LEBESGUE MEASURE Most

RANDOMNESS – BEYOND LEBESGUE MEASURE JAN REIMANN ABSTRACT. Much of the recent research on algorithmic randomness has focused on randomness for Lebesgue measure. While, from a com- putability theoretic point of view, the picture remains unchanged if one passes to arbitrary computable measures, interesting phenomena occur if one studies the the set of reals which are random for an arbitrary (contin- uous) probability measure or a generalized Hausdorff measure on Cantor space. This paper tries to give a survey of some of the research that has been done on randomness for non-Lebesgue measures. 1. INTRODUCTION Most studies on algorithmic randomness focus on reals random with respect to the uniform distribution, i.e. the (1/2, 1/2)-Bernoulli measure, which is measure theoretically isomorphic to Lebesgue measure on the unit interval. The theory of uniform randomness, with all its ramifications (e.g. computable or Schnorr randomness) has been well studied over the past decades and has led to an impressive theory. Recently, a lot of attention focused on the interaction of algorithmic ran- domness with recursion theory: What are the computational properties of random reals? In other words, which computational properties hold effec- tively for almost every real? This has led to a number of interesting re- sults, many of which will be covered in a forthcoming book by Downey and Hirschfeldt [12]. While the understanding of “holds effectively” varied in these results (depending on the underlying notion of randomness, such as computable, Schnorr, or weak randomness, or various arithmetic levels of Martin-Lof¨ randomness, to name only a few), the meaning of “for almost every” was usually understood with respect to Lebesgue measure. -

Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory

Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory by David Worth B.S., Mathematics, University of New Mexico, 2003 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Mathematics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2006 c 2008, David Worth iii DEDICATION To my lovely wife Meghan, to whom I am eternally grateful for her support and love. Without her I would never have followed my education or my bliss. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Terry Loring, for his years of encouragement and aid in pursuing mathematics. I would also like to thank Dr. Cristina Pereyra for her unfailing encouragement and her aid in completing this daunting task. I would like to thank Dr. Wojciech Kucharz for his guidance and encouragement for the entirety of my adult mathematical career. Moreover I would like to thank Dr. Jens Lorenz, Dr. Vladimir I Koltchinskii, Dr. James Ellison, and Dr. Alexandru Buium for their years of inspirational teaching and their influence in my life. v Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory by David Worth ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Mathematics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2006 Construction of Geometric Outer-Measures and Dimension Theory by David Worth B.S., Mathematics, University of New Mexico, 2003 M.S., Mathematics, University of New Mexico, 2008 Abstract Geometric Measure Theory is the rigorous mathematical study of the field commonly known as Fractal Geometry. In this work we survey means of constructing families of measures, via the so-called \Carath´eodory construction", which isolate certain small- scale features of complicated sets in a metric space. -

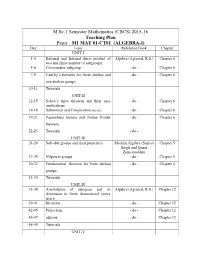

M.Sc. I Semester Mathematics (CBCS) 2015-16 Teaching Plan

M.Sc. I Semester Mathematics (CBCS) 2015-16 Teaching Plan Paper : M1 MAT 01-CT01 (ALGEBRA-I) Day Topic Reference Book Chapter UNIT-I 1-4 External and Internal direct product of Algebra (Agrawal, R.S.) Chapter 6 two and finite number of subgroups; 5-6 Commutator subgroup - do - Chapter 6 7-9 Cauchy’s theorem for finite abelian and - do - Chapter 6 non abelian groups. 10-11 Tutorials UNIT-II 12-15 Sylow’s three theorem and their easy - do - Chapter 6 applications 16-18 Subnormal and Composition series, - do - Chapter 6 19-21 Zassenhaus lemma and Jordan Holder - do - Chapter 6 theorem. 22-23 Tutorials - do - UNIT-III 24-26 Solvable groups and their properties Modern Algebra (Surjeet Chapter 5 Singh and Quazi Zameeruddin) 27-29 Nilpotent groups - do - Chapter 5 30-32 Fundamental theorem for finite abelian - do - Chapter 4 groups. 33-34 Tutorials UNIT-IV 35-38 Annihilators of subspace and its Algebra (Agrawal, R.S.) Chapter 12 dimension in finite dimensional vector space 39-41 Invariant, - do - Chapter 12 42-45 Projection, - do - Chapter 12 46-47 adjoins. - do - Chapter 12 48-49 Tutorials UNIT-V 50-54 Singular and nonsingular linear Algebra (Agrawal, R.S.) Chapter 12 transformation 55-58 quadratic forms and Diagonalization. - do - Chapter12 59-60 Tutorials - do - 61-65 Students Interaction & Difficulty solving - - M.Sc. I Semester Mathematics (CBCS) 2015-16 Teaching Plan Paper : M1 MAT 02-CT02 (REAL ANALYSIS) Day Topic Reference Book Chapter UNIT-I 1-2 Length of an interval, outer measure of a Theory and Problems of Chapter 2 subset of R, Labesgue outer measure of a Real Variables: Murray subset of R R. -

Section 17.5. the Carathéodry-Hahn Theorem: the Extension of A

17.5. The Carath´eodory-Hahn Theorem 1 Section 17.5. The Carath´eodry-Hahn Theorem: The Extension of a Premeasure to a Measure Note. We have µ defined on S and use µ to define µ∗ on X. We then restrict µ∗ to a subset of X on which µ∗ is a measure (denoted µ). Unlike with Lebesgue measure where the elements of S are measurable sets themselves (and S is the set of open intervals), we may not have µ defined on S. In this section, we look for conditions on µ : S → [0, ∞] which imply the measurability of the elements of S. Under these conditions, µ is then an extension of µ from S to M (the σ-algebra of measurable sets). ∞ Definition. A set function µ : S → [0, ∞] is finitely additive if whenever {Ek}k=1 ∞ is a finite disjoint collection of sets in S and ∪k=1Ek ∈ S, we have n n µ · Ek = µ(Ek). k=1 ! k=1 [ X Note. We have previously defined finitely monotone for set functions and Propo- sition 17.6 gives finite additivity for an outer measure on M, but this is the first time we have discussed a finitely additive set function. Proposition 17.11. Let S be a collection of subsets of X and µ : S → [0, ∞] a set function. In order that the Carath´eodory measure µ induced by µ be an extension of µ (that is, µ = µ on S) it is necessary that µ be both finitely additive and countably monotone and, if ∅ ∈ S, then µ(∅) = 0.