Crusades and Dcrusading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-June-Thistle

Tundra Thistle The Newsletter of the Alaskan Scottish Club Volume 26 Number 6 June 2020 Coming Events: Midsummer in Scotland ASC Adopts a Trail! By Rev. Amberle Wright Midsummer is when we see the turning of the year as the By Preston McKee days begin to shorten and the moods of the people turn to Alaskan Scottish Club – Cleaning the Trail one piece of more fun and festive celebrations. Midsummer falls rubbish at a time. between the planting and harvesting of crops, leaving people who worked the land time to relax. The atmosphere The Alaskan Scottish Club has adopted a 2 mile section of of the many different rituals and celebrations held all over the Campbell Creek Trail as part of Anchorage‟s Tail Scotland is relaxed with a mix of anticipation. The festival Clean-Up Program. Our section runs between Victor (Off of Midsummer is primarily a Celtic fire festival traditionally Dimond) and the pavilion at Taku Lake and Stormy Pl. (off celebrated on either the 23rd or 24th of June, although the Dimond). longest day actually falls on the 21st. It‟s easy to take a walk and do some good at the same Some of the earliest mentions of Midsummer celebrations time. Please join us twice a month (or whenever you can) in Scotland date back to the sixteenth century. We can find and help us pick up rubbish from the trail and spend some the evidence of its importance to our ancestors in the large time outside in the fresh air with a friendly, lively group of number of stone circles and other ancient monuments that people. -

The Clan Macleod Society of Australia (NSW) Inc

The Clan MacLeod Society of Australia (NSW) Inc. Newsletter June 2011 Chief: Hugh MacLeod of MacLeod Chief of Lewes: Torquil Donald Macleod of Lewes Chief of Raasay: Roderick John Macleod of Raasay President: Peter Macleod, 19 Viewpoint Drive, Toukley 2263. Phone (02) 4397 3161 Email: [email protected] Secretary: Mrs Wendy Macleod, 19 Viewpoint Drive, Toukley 2263. Phone (02) 4397 3161 Treasurer: Mr Rod McLeod, 62 Menzies Rd, Eastwood 2122. Ph (02) 9869 2659 email: [email protected] Annual Subscription $28 ($10 for each additional person in Important Dates the one home receiving one Clan Magazine & Newsletter, Sat 2 July Aberdeen Highland Gathering see last Newsletter. i.e. One person $28, Two people $38, Three people $48, Sat. 27 Aug. Toukley Gathering of the Clans - see inside. etc.). Subscriptions are due on 30th June each year. Sat. 3rd Sept. - Luncheon and AGM - see below. Dear Clansfolk, Banner bearers for the Kirkin’ It’s AGM and Membership renewal time. AGM details are below and a Membership Renewal enclosed. At the risk of being repetitious, in order to pass the Constitutional changes we need a good turnout at the AGM this year. Peter AGM Saturday 3rd Sept. Venue is Forestville RSL Club, Melwood Ave, Forestville. We will reserve tables in the Bistro for lunch from 12 noon. You can attend the lunch or the meeting, or both. Bistro prices are reasonable and Charles Cooke & Peter Macleod afternoon timing means no night travelling. We would like to know approximate numbers, so if you are coming could Glen Innes Celtic Festival 29th Apr to 1st May you please phone one of the office bearers at the head of Again our Clan was well represented at this popular and well this page. -

The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer (Coinneach Odhar Fiosaiche)

GIFT OF I ft i THE PROPHECIES BRAHAN SEER (COINNEACH ODHAR FIOSAICHE). BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. Scot, EDITOR OF THE "CELTIC MAGAZINE"; AUTHOR OF " THE HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES," " THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES," ETC., ETC. ^hirb ®bittx>ii—JEtirk (Enlargeb. WITH AN APPENDIX ON THE SUPERSTITION OF THE HIGHLANDERS, BY THE REV. ALEXANDER MACGREGOR, M.A. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE, "Celtic Magazine" Office, 1882. ^\ yf'.^ A. KING AND COMPANY, PRINTERS TO THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN. <> DEDICATION TO FIRST EDITION. TO MY REVERED FRIEND, THE REV. ALEXANDER MACGREGOR, M.A., Of the West Church, Inverness, as a humble tribute of my admiration of his many virtues, his genial nature, and his manly Celtic spirit. He has kept alive the smouldering embers of our Celtic Literature for half a century by his contributions, under the signature of " Sgiathanach," " Alas- tair Ruadh," and others, to the Teachdaire Gatdhealach, Cuairtear nan Gleann, Fear Tathaich tian Beann, An Gaidheal, The Highlander ; and, latterly, his varied and interesting articles in the Celtic Magazine have done much to secure to that Periodical its present, and rapidly increasing, popularity. He has now the pleasing satisfaction, in his ripe and mellow old age, of seeing the embers, which he so long and so carefully fostered, shining forth in the full blaze of a general admiration of the long despised and ignored Literature of his countrymen ; and to him no small share of the honour is due. That he may yet live many years in the enjoyment of health and honour, is the sincere desire of many a High- lander, and of none more so, than of his sincere friend, ALEXANDER MACKENZIE. -

Scotland-The-Isle-Of-Skye-2016.Pdf

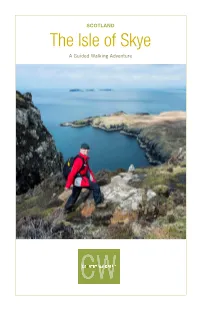

SCOTLAND The Isle of Skye A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Scotland at a Glance .............................................................. 22 Packing List ........................................................................... 26 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our new optional Flight + Tour Combo and PrePrePre-Pre ---TourTour Edinburgh Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview Unparalleled scenery, incredible walks, local folklore, and history come together effortlessly in the Highlands and -

History of the Macleods with Genealogies of the Principal

*? 1 /mIB4» » ' Q oc i. &;::$ 23 j • or v HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS. INVERNESS: PRINTED AT THE "SCOTTISH HIGHLANDER" OFFICE. HISTORY TP MACLEODS WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. Scot., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY AND GENEALOGIES OF THE CLAN MACKENZIE"; "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERON'S;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS ; " "THE " PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER ; " THE HISTORICAL TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLANDS;" "THE HISTORY " OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" " THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE IN 1882-83;" ETC., ETC. MURUS AHENEUS. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXXIX. J iBRARY J TO LACHLAN MACDONALD, ESQUIRE OF SKAEBOST, THE BEST LANDLORD IN THE HIGHLANDS. THIS HISTORY OF HIS MOTHER'S CLAN (Ann Macleod of Gesto) IS INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/historyofmacleodOOmack PREFACE. -:o:- This volume completes my fifth Clan History, written and published during the last ten years, making altogether some two thousand two hundred and fifty pages of a class of literary work which, in every line, requires the most scrupulous and careful verification. This is in addition to about the same number, dealing with the traditions^ superstitions, general history, and social condition of the Highlands, and mostly prepared after business hours in the course of an active private and public life, including my editorial labours in connection with the Celtic Maga- zine and the Scottish Highlander. This is far more than has ever been written by any author born north of the Grampians and whatever may be said ; about the quality of these productions, two agreeable facts may be stated regarding them. -

Clan Macleod Publication S

P b ic 0 I . Cl n MacLeod u l ation s N . a . T H E MAQLEO DS E A S H O R T S KETC H O F T H E IR C LAN , - AN D H ISTO RY, FO LK LO R E , TALE S , BIOG R APH ICAL NOT IC ES O F SO M E E MIN E NT C LANS ME N. BY TH E ' R E Y. R . C . M A C L E OD OF MACLE OD . PUBLISH E D BY TH E CL AN M ACL E OD SOCIE TY , E D IN BUR GH . Land o f th e be autiful and brave ’ — ’ Th e fre e man s hom e th e martyr s grave Th e n rse r o f an m e n u y gi t , W ose e e s a n e w e e r e n h d d h ve li k d ith v y gl , An d e e r an d e e r s ream v y hill , v y t , Th e ro man ce of som e w arrior d re am n e e r m a a son o f n e v y thi , ’ te re e r his w an e r n s e s n c ne d i g t p i li , Fo rge t th e sky w hich be n t abo ve H is childh o od like a dre am o f lo ve ’ G Wh ttiea' J . -

Gaelic Names of Pibrochs a Concise Dictionary Edited by Roderick D

February 2013 Gaelic names of Pibrochs A Concise Dictionary edited by Roderick D. Cannon Introduction Sources Text Bibliography February 2013 Introduction This is an alphabetical listing of the Gaelic names of pibrochs, taken from original sources. The great majority of sources are manuscript and printed collections of the tunes, in music notation appropriate for the bagpipe, that is, in staff notation or in canntaireachd. In addition, there are a few arranged for piano or fiddle, but only when the tunes correspond to known bagpipe versions. The main purpose of the work is to make available authentic versions of all authentic names, to explain apparent inconsistences and difficulties in translation, and to account for the forms of the names as we find them. The emphasis here is on the names, not the tunes as such. Many tunes have a variety of different names, but here the variants are only listed in the same entry when they are evidently related. Names which are semantically unrelated are placed in separate entries, even when linked by tradition such as Craig Ealachaidh and Cruinnneachdh nan Grandach. But in such cases they are linked by cross-references, and the traditions which explain the connection are mentioned in the discussions. Different names which merely sound similar are also cross-referenced, whether or not they apply to the same tune. Different names for the same tune, with no apparent connection, are not cross-referenced. Different tunes with the same name are given separate entries, though of course these appear consecutively in the list. In each entry the first name, in bold type, is presented in modern Gaelic spelling except that the acute accent is retained, e.g. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

Parliament 2010 Dunvegan Programme • Dunvegan Taxis 01470 521560 (Within the Village)

Page 24 Dunvegan Programme General information in Dunvegan EMERGENCY INFORMATION Police and fire • The Emergency number for Ambulance, Police and Fire in the UK is 999. • 999 can be dialled from a mobile phone or telephone booth at no charge. Dunvegan programme 2010 Medical and dental emergencies • Regardless of your nationality or your home health care provider or insurance, if you A warm and hearty welcome! need ambulatory health care or advice you can call the National Health Service at Some of our Parliamentarians will be joining us after a memorable trip to Assynt, 08454 242424. others will be weary from the midges and mud of the North Room Group service project, but most of us will arrive “fresh” from many hours of travelling. FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE Whether you are a first-timer at Parliament or a practiced expert, you will find here • There are two “big” banks in the square in Portree: Halifax Bank of Scotland and Royal friends and family that you have never met before, but feel wonderfully familiar. It’s time Bank of Scotland. Both banks have 24 hour ATM machines. to take a deep breath and immerse yourself in the very large and complex world of the • In Dunvegan, cash withdrawals can be made from the Link ATM at Fasgadh (village MacLeods, discover our “Old and New Traditions”, and participate in the many food store) or possibly the Royal Bank of Scotland’s mobile banking unit. (If the educational and social activities at Parliament. mobile unit is available, hours will be posted at the Information Point. -

Bloody Bay and the Macleods

BLOODY BAY AND THE MACLEODS The battle of Bloody Bay was fought on some date between 1481 and 1485,1 say c.1483, and saw the death of William MacLeod of Harris2 (who had been chief of the Siol Tormoid since the death of his father, Ian Borb, 1463x1469, say c.1466),3 who was succeeded by his son, Alasdair Crotach (who did not die until 1546/7).4 With regard to the identity and genealogy of the combatants at Bloody Bay there is no problem with the Harris MacLeods but there is one with the Lewis MacLeods, which is the concern of the second part of this paper. Citing “Seanachie’s Account of the Clan Maclean (1838), p.24,” which states that the battle “was fought off Barrayraig near Tobermory in Mull, at a place ever since known by the name of Ba ’na falla, or the Bloody Bay”, R. W. Munro wrote “The name Bloody Bay, even in Gaelic, sounds somewhat artificial, and I wonder if anyone has heard it or any other name used by native Gaelic speakers in Mull or elsewhere for the sea-fight”.5 The requested “any other name” for the battle is found in MacLeod tradition. The chapter on the MacLeods of that ilk (i.e. of Harris) in Douglas’s Baronage ends its account of “XI. WILLIAM” with:6 “ This William, by order of king James III. went to the aſſiſtance of John earl of Roſs against his natural ſon, and loſt his life in a naval engagement in Cammiſteraig, or Bloody Bay, in the Sound of Mull, and was ſucceeded by his only ſon, XII. -

The Macleods of Dunvegan

M-'{\c V\>"V j\^: Ihv^^ THE MACLEODS OF DUNVEGAN Photo, by Moffat, Bdhibur.-h. Norman, Twenty-third Chief of MacLeod. Frontispiece. THE MACLEODS OF DUNVEGAN From the Time of Leod to the End of the Seventeenth Century BASED UPON THE BANNATYNE MS. AND ON THE PAPERS PRESERVED IN THE DUNVEGAN CHARTER CHEST BY THE REV. CANON R. C. MACLEOD OF MACLEOD PRIVATELY PRINTED FOR THE CLAN MACLEOD SOCIETY 1927 o^ ^ B -'l')^"> [Art DEDICATED TO MY FELLOW CLANSMEN AND CLANSWOMEN IN ALL PARTS OF THE WORLD FOREWORD By Sir JOHN LORNE MACLEOD. G.B.E., LL.D. I HAVE the honour to make a few preHminary remarks upon the issue of the present volume. I presume to say forthwith that this result of the labours and investigation of the learned writer concerning the origin and history of our Clan will be welcomed by every one of the name, and associated with the name, both at home and overseas. We are all under a deep debt of gratitude to Canon R. C. MacLeod of MacLeod for yield- ing to our solicitations, and thus making available in permanent form his great store of knowledge upon a subject which inspires our pride and patriotism, and reanimates our spirit of continuing clanship. We express our high loyalty to our revered and honoured Chief—MacLeod of MacLeod—and to the House of Dunvegan. This volume, though particularly relating to ' The MacLeods of Dunvegan ' —and so limited in its title, as is properly the case, having regard to the special sources of information founded on—is not, however, thus exclusive in its scope. -

A Map of the Pibroch Landscape, 1760 –1841

PIBROCH by Barnaby Brown A map of the pibroch landscape, 1760 –1841 HE survey presented on these six pages is a TABLE 1. 311 tunes ordered by palette and pitch height tidy-up operation. For twenty years, I have Tworked around usability issues with existing 4-pitch tunes (6%) tables of data, including my own. I frequently found G A B C - - - - (A) 12 Square Rea’s March WW myself bamboozled, unable to find a particular setting, G A B C - - - - (A) 16 The Gordons’ Salute W or discovering that inherited data didn’t correspond G A B C - - - - - 215 MacLeod of Gesto’s Gathering P with reality. Given the complexity produced by several G A B C - (E) - - - 314 Hindo hindo hindo rõdin W generations of oral transmission, it is unsurprising that G A B - D (E - G A) 170 Glengarry’s March W G B the task of mapping this material has been challenging. A - D - - - - 285 Lament for Allan Og RL G A B - D - - - - 104 O Face so Fair W The deficiencies of previous surveys, however, are small G A B - D - - - - 107 The Tune of Strife O compared to the debt I owe to those who worked un- - A B C D - - - (A) 153 White Wedder Black Tail I der harder conditions, drawing connections between - A B C - E - - - 9 The MacNabs’ Gathering RL sources for the first time. It is thanks to the generosity - A B C - E - - (A) 13 The Rout of Glenfruin W of previous explorers, taking the trouble to share their - A B C - E - - - 301 MacLeod of Tallisker’s Salute W discoveries, that I have been able to produce a map - A B C - E - (G A) 36 One of the Cragich: Hiharin hiodreen P which is more powerful and user-friendly.