MATTHEW HIGGS and Paul O'neill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Wylie 'Tilt the Horizontal Into a Slant'

Rose Wylie Tilt The Horizontal Into A Slant 4 TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT 5 INTRO Rose Wylie’s pictures are bold, occasionally chaotic, often unpredictable, and always fiercely independent, without being domineering. Wylie works directly on to large unprimed, unstretched canvases and her inspiration comes from many and varied sources, most of them popular and vernacular. The cutout techniques of collage and the framing devices of film, cartoon strips and Renaissance panels inform her compositions and repeated motifs. Often working from memory, she distils her subjects into succinct observations, using text to give additional emphasis to her recollections. Wylie borrows from first-hand imagery of her everyday life as well as films, newspapers, magazines, and television allowing herself to follow loosely associated trains of thought, often in the initial form of drawings on paper. The ensuing paintings are spontaneous but carefully considered: mixing up ideas and feelings from both external and personal worlds. Rose Wylie favours the particular, not the general; although subjects and meaning are important, the act of focused looking is even more so. Every image is rooted in a specific moment of attention, and while her work is contemporary in terms of its fragmentation and cultural references, it is perhaps more traditional in its commitment to the most fundamental aspects of picturemaking: drawing, colour, and texture. 8 TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT TILT THE HORIZONTAL INTO A SLANT 9 COMING UNSTUCK the power zing back and forth between the painting and us, the viewer? It’s both elegant It may come as a surprise to some, when and inelegant but never either ‘quirky’ or considering Wylie’s work that words like ‘power’ ‘goofy’. -

Artist of the Day 2016 F: +44 (0)20 7439 7733

PRESS RELEASE T: +44 (0)20 7439 7766 ARTIST OF THE DAY 2016 F: +44 (0)20 7439 7733 21 Cork Street 20 June - 2 July 2016 London W1S 3LZ Monday - Friday 11am - 7pm [email protected] Saturday - 11am - 6pm www.flowersgallery.com Flowers Gallery is pleased to announce the 23rd edition of Artist of the Day, a valuable platform for emerging artists since 1983. The two-week exhibition showcases the work of ten artists, nominated by prominent figures in contemporary art. The criteria for selection is talent, originality, promise and the ability to benefit from a one-day solo exhibition of their work at Flowers Gallery, Cork Street. “Every year we look forward to encountering the unknown and unpredictable. The constraint of time to install and promote an exhibition for one day only ensures there is a tangible energy in the gallery, with each day’s show incomparable to the other days. Artist of the Day has given a platform and context to artists who may not have exhibited much before, accompanied by the support and dedication of their selectors. The relationship between the selector and the artist adds an intimate power to the installations, and as a gallery we have gone on to work with many of the selected artists long term.” – Matthew Flowers Past selectors have included Patrick Caulfield, Helen Chadwick, Jake & Dinos Chapman, Tracey Emin, Gilbert & George, Maggi Hambling, Albert Irvin, Cornelia Parker, Bridget Riley and Gavin Turk; while Billy Childish, Adam Dant, Dexter Dalwood, Nicola Hicks, Claerwen James and Seba Kurtis, Untitled, 2015, Lambda C-Type print Lynette Yiadom-Boakye have featured as chosen artists. -

Art and Design Advanced Unit 4: A2 Externally Set Assignment

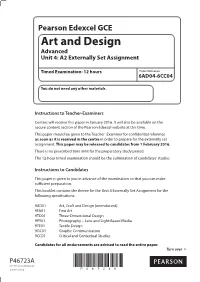

Pearson Edexcel GCE Art and Design Advanced Unit 4: A2 Externally Set Assignment Timed Examination: 12 hours Paper Reference 6AD04-6CC04 You do not need any other materials. Instructions to Teacher-Examiners Centres will receive this paper in January 2016. It will also be available on the secure content section of the Pearson Edexcel website at this time. This paper should be given to the Teacher–Examiner for confidential reference as soon as it is received in the centre in order to prepare for the externally set assignment. This paper may be released to candidates from 1 February 2016. There is no prescribed time limit for the preparatory study period. The 12-hour timed examination should be the culmination of candidates’ studies. Instructions to Candidates This paper is given to you in advance of the examination so that you can make sufficient preparation. This booklet contains the theme for the Unit 4 Externally Set Assignment for the following specifications: 9AD01 Art, Craft and Design (unendorsed) 9FA01 Fine Art 9TD01 Three-Dimensional Design 9PY01 Photography – Lens and Light-Based Media 9TE01 Textile Design 9GC01 Graphic Communication 9CC01 Critical and Contextual Studies Candidates for all endorsements are advised to read the entire paper. Turn over P46723A ©2016 Pearson Education Ltd. *P46723A* 1/1/1/1/1/1/c2 Each submission for the A2 Externally Set Assignment, whether unendorsed or endorsed, should be based on the theme given in this paper. You are advised to read through the entire paper, as helpful starting points may be found outside your chosen endorsement. If you are entered for an endorsed specification, you should produce work predominantly in your chosen discipline for the Externally Set Assignment. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Mark Dean Education 2017-2020 Encounter, London Centre for Spiritual Direction 2007-2010 Diphe Contextual Theology, St Mellitus

Mark Dean Education 2017-2020 Encounter, London Centre for Spiritual Direction 2007-2010 DipHE Contextual Theology, St Mellitus College 1992-1994 MA Fine Art, Goldsmiths' College 1989-1991 PGDip Youth & Community Work, Thames Polytechnic 1977-1980 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Brighton Polytechnic Solo Exhibitions & Projects 2020 Stations 2020, Arts Chaplaincy Projects (online project with socially distanced contributors) 2019 Where We Are, Laban Theatre, London (video and dance collaboration) 2019 All Angels, Marlborough College Chapel 2019 Color Motet, Austin Forum, London 2019 Pastiche Mass, Arts Chaplaincy Projects, London 2017 Stations of the Resurrection, St Paul's Cathedral, London (dance by Lizzi Kew Ross & Co) 2017 Stations of the Cross, St Stephen Walbrook, London 2014 Christian Disco, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam 2011 My Mum (V2-Sensitive), Beaconsfield, London 2010 The Beginning of The End, Beaconsfield, London 2007 Scorpio Rising 2, Holy Trinity & St Mary, Berwick-upon-Tweed 2006 Masochistic Opposite, Matthew Bown Gallery, London 2005 (Version) for Lightsilver, Beaconsfield, London 2004 Disco Maquette, Sketch, London 2002 The Return of JacKie & Judy (+Joey), Laurent Delaye Gallery, London 2002 MarK Dean, Volker Diehl Gallery, Berlin 2001 MarK Dean, IKON Gallery, Birmingham 2001 MarK Dean, Evolution, Leeds International Film Festival 2000 Ascension, Laurent Delaye Gallery, London 2000 MarK Dean, Imago 2000, Casa de las Conchas, Salamanca 1999 Dust, Laurent Delaye Gallery, London 1996 MarK Dean, City Racing, London Selected -

Artist Billy Childish Comes of Age

Artist Billy Childish comes of age Once known mainly for his relationship with artist Tracey Emin, Billy Childish, co-founder of the Stuckist movement – and a man of many names – has finally come into his own, writes Fionnuala McHugh 5 APR 2014 / UPDATED ON 15 MAY 2015 Childish in his studio. Photo by Fionnuala McHugh Billy Childish is a musician, a poet, a novelist, a photographer and a painter. Unless you’re familiar with the independent British music scene of the late 1970s and early 80s, however, you almost certainly won’t have heard of him. Until recently, he tended to be defined via his relationship with a rather better-known British artist called Tracey Emin, with whom he’d had a relationship in the 80s. If his name was known to the general public at all, it was because it had been stitched, along with many others, on to a tent in her seminal opus Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963 – 1995. One exasperated day, Emin yelled at Childish, “Your paintings are stuck. You are stuck, stuck, stuck!” As a result of this observation, the Stuckist art movement was formed in 1999 (whereupon the friendship with Emin foundered for about a decade). The Stuckists were against conceptual art of which embroidered tents, rotting sharks, blaspheming elephant dung, etc were only the most obvious examples. A core belief of the Stuckists was that “artists who don’t paint aren’t artists”, and although Childish left the movement a couple of years later, this is the way he continues to think. -

Billy Childish Flowers, Nudes and Birch Trees: New Paintings 2015 September 10-October 31, 2015 536 West 22Nd Street, New York #Billychildish

Billy Childish flowers, nudes and birch trees: New Paintings 2015 September 10-October 31, 2015 536 West 22nd Street, New York #billychildish Opening Reception: Thursday, September 10, 6-8PM birch wood, 2015, oil and charcoal on linen, 72.05 x 108.07 inches, 183 x 274.5 cm. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong. New York, August 11, 2015—Lehmann Maupin is pleased to present its fourth exhibition with British artist Billy Childish, a prolific painter, writer, and musician. The artist’s vivid oil paintings offer fragmented fields of intense color applied frenetically, often leaving charcoal marks and the linen canvas exposed, further emphasizing the immediate and intuitive nature of Childish’s work. The artist will be present for an opening reception at the gallery on Thursday, September 10 from 6-8PM. Working in traditional genres such as portraiture, still life, and landscape, Childish’s paintings are spiritually charged expressions that come from a place of deep personal meaning. These powerful works, including unabashed nudes, self-portraits, and dense woodland scenes, honor the simple nature of being and in the process transcend the ordinary. Eschewing any hint of post-modernist irony in his work, he allows the basics of personal expression to come forth through the fundamentals of painting. A self-proclaimed “Radical Traditionalist,” Childish has said, “The reason I honor tradition is that it provides a form and structure that allows freedom—the ego is subjugated and the requirements of the painting are met. Tradition is not to be worshipped or adored; it is a vehicle to take you to new places, or we could say to arrive at the perennial.” While he is occasionally associated with British groups like the Stuckists and YBAs, Childish does not see himself as connected to a particular contemporary movement; however, he is highly regarded and well known by his peers, including renowned artists Peter Doig and Tracey Emin. -

Bortolami Gallery Through June 15Th, 2019.” Art Observed, May 30Th, 2019, Illus

BORTOLAMI Virginia Overton (b. 1971 in Nashville, Tennessee) Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York Education 2005 University of Memphis, TN, MFA 2002 University of Memphis, TN, BFA Solo Exhibitions 2019 Água Viva, Bortolami, New York, NY Francesca Pia, Zürich, Switzerland (forthcoming) 2018 Built, Don River Valley Park, Toronto, Canada secret space, Biel, Switzerland Built, Socrates Sculpture Park, Queens, NY Virginia Overton, University of Memphis Fogelman Galleries, Memphis, TN 2017 Why?! Why Did You Take My Log?!?!, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tucson, AZ 2016 Winter Garden, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY White Cube Bermondsey, London, England Sculpture Gardens, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT 2015 White Cube, London, England 2014 Flat Rock, Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, North Miami, FL 2013 Westfälischer Kunstverein, Munster, Germany Kunsthalle Bern, Bern, Switzerland Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, NY 2012 The Kitchen, New York, NY Deluxe, The Power Station, Dallas, TX 2011 Freymond-Guth, Zürich, Switzerland 2010 Untitled (Milano), N.O. Gallery, Milan, Italy Cheekwood Museum of Art, Nashville, TN True Grit, Dispatch, New York, NY 2008 Moving on South, curated by Dana Orland, White Box, New York, NY This Is Not A Ladder, Artlab at AMUM, Memphis, TN 39 WALKER STREET NEW YORK NY 10013 T 212 727 2050 BORTOLAMIGALLERY.COM BORTOLAMI 2007 Skytracker, Powerhouse, Memphis, TN Selected Group Exhibitions 2019 Downtown Painting, curated by Alex Katz, Peter -

Matthew Higgs

The Museum of Everything Exhibition #4 Conversation with Matthew Higgs Matthew Higgs b 1964 (Wakefield, England) Matthew Higgs is an artist, curator, writer and director of White Columns Gallery, New York. Former director of exhibitions at the ICA in London (1996/9) and a former curator at the Wattis Institute in San Francisco (2001/4), Higgs was a contributor and speaker at Exhibition #1 and has ex- hibited the work of Creative Growth artists Dan Miller (2011) and William Scott (2009), both featured in Exhibition #4. [START] MoE: Matthew, I wondered if we could talk a little about your involvement with self-taught art and in particular with the artists at Creative Growth. You have curated the work of Judith Scott, Dan Miller, William Scott and Aurie Ramirez, I wondered if you could articulate what it is you feel is important about these artists and what they mean in terms of our understanding of art? MH: When I first came across Creative Growth ten years ago, my limited understanding of self-taught, outsider artists and creativity in relation to disabilities, was naï ve at best. Encountering an organisation like Crea- tive Growth forced me to think about my own relationship with this work and with art in general. I had spent most of the 1990s teaching undergraduate and graduate level in art schools. What was interesting was just how different the atmosphere was at Creative Growth. Art was being made for reasons that remained out of reach. The emphasis in conventional art schools is a pressure to ex- plain, to defend one’s intellectual and aesthetic territories. -

An Analysis of New York and London Fine Art Schools' Responses to the Market in Pedagogy and Curricula Adelaide Dunn

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2018 From the Academy to the Marketplace: An analysis of New York and London Fine Art Schools' Responses to the Market in Pedagogy and Curricula Adelaide Dunn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Higher Education Commons From the Academy to the Marketplace: An Analysis of New York and London Fine Art Schools’ Responses to the Market in Pedagogy and Curricula By Adelaide Dunn A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for a Master of Arts in Art Business Sotheby’s Institute of Art, New York 2018 14,976 words Abstract As fine art degrees expand in cost and popularity, the need to educate students about the complex art market they are entering is more urgent now than ever before. But despite the globalizing art market’s continuing demand for emerging talent, its opaque and hypercompetitive nature generates significant obstacles for fine art graduates. This is exacerbated by the relative absence of practical business and legal skills implemented in fine art curricula across the U.S. and U.K. Statistical and anecdotal evidence highlighting the many entrepreneurial skills required to develop and sustain a professional practice, demonstrates the need for more comprehensive professional development syllabi to be implemented in fine art schools. This thesis takes as its main focus the art markets of New York and London, and assesses how fine art schools in these rapidly intensifying urban centers respond to their commercial environments. -

About Henry Street Settlement

TO BENEFIT Henry Street Settlement ORGANIZED BY Art Dealers Association of America March 1– 5, Gala Preview February 28 FOUNDED 1962 Park Avenue Armory at 67th Street, New York City MEDIA MATERIALS Lead sponsoring partner of The Art Show The ADAA Announces Program Highlights at the 2017 Edition of The Art Show ART DEALERS ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA 205 Lexington Avenue, Suite #901 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] www.artdealers.org tel: 212.488.5550 fax: 646.688.6809 Images (left to right): Scott Olson, Untitled (2016), courtesy James Cohan; Larry Bell with Untitled (Wedge) at GE Headquarters, Fairfield, CT in 1984, courtesy Anthony Meier Fine Arts; George Inness, A June Day (1881), courtesy Thomas Colville Fine Art. #TheArtShowNYC Program Features Keynote Event with Museum and Cultural Leaders from across the U.S., a Silent Bidding Sale of an Alexander Calder Sculpture to Benefit the ADAA Foundation, and the Annual Art Show Gala Preview to Benefit Henry Street Settlement ADAA Member Galleries Will Present Ambitious Solo Exhibitions, Group Shows, and New Works at The Art Show, March 1–5, 2017 To download hi-res images of highlights of The Art Show, visit http://bit.ly/2kSTTPW New York, January 25, 2017—The Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) today announced additional program highlights of the 2017 edition of The Art Show. The nation’s most respected and longest-running art fair will take place on March 1-5, 2017, at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, with a Gala Preview on February 28 to benefit Henry Street Settlement. -

Thecollective

WORKPLACEGATESHEAD The Old Post Office 19-21 West Street Gateshead, NE8 1AD thecollective Preview: Friday 5th May 6pm – 8pm Exhibition continues: 6th May – 3rd June Opening hours: Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm Issued Wednesday 26th April 2018 Workplace Gateshead is delighted to present the first public exhibition of selected works from The Founding Collective. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Started in 2002 in London by a group of art professionals and families interested in living with contemporary art The Collective is a growing network of groups collecting, sharing and enjoying contemporary art in their homes or places of work. The combined collection of The Founding Group now comprises over 60 original and limited edition works by emerging and established artists. Selected by Workplace this exhibition includes works by: Mel Brimfield, Jemima Brown, Fiona Banner, Libia Castro & Olafur Olafsson, Martin Creed, Tom Dale, Michael Dean, Tacita Dean, Peter Doig, Bobby Dowler, Tracey Emin, Erica Eyres, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Ceal Floyer, Matthew Higgs, Gareth Jones, Alex Katz, Scott King, Jochen Klein, Edwin Li, Hilary Lloyd, Paul McCarthy, Paul Noble, Chris Ofili, Peter Pommerer, James Pyman, Frances Richardson, Giorgio Sadotti, Jane Simpson, Wolfgang Tillmans, Piotr Uklanski, Mark Wallinger, Bedwyr Williams, and Elizabeth Wright. Free public event: Friday 5th May, 5pm - 6pm, all welcome Founding members of The Collective will give an informal introduction to the history of the group, how it works, how it expanded and plans for the future. This will be followed by an open discussion chaired by WORKPLACE directors Paul Moss and Miles Thurlow focusing on the importance of collecting contemporary art, how to make a start regardless of budget, and the challenges and opportunities for new collectors in the North of England.