Epidemiological Model in TRAUMA TEAM 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year Ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries Years ended March 31, 1998, 1999 and 2000 Thousands of Millions of yen U.S. dollars 1998 1999 2000 2000 For the year: Net sales: Consumer products ........................................................................................................ ¥114,457 ¥084,694 ¥186,189 $1,754,018 Amusement center operations ...................................................................................... 94,521 93,128 79,212 746,227 Amusement machine sales............................................................................................ 122,627 88,372 73,654 693,867 Total ........................................................................................................................... ¥331,605 ¥266,194 ¥339,055 $3,194,112 Cost of sales ...................................................................................................................... ¥270,710 ¥201,819 ¥290,492 $2,736,618 Gross profit ........................................................................................................................ 60,895 64,375 48,563 457,494 Selling, general and administrative expenses .................................................................. 74,862 62,287 88,917 837,654 Operating (loss) income ..................................................................................................... (13,967) 2,088 (40,354) (380,160) Net loss............................................................................................................................. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

MEDIA CONTACT: Aram Jabbari Atlus U.S.A., Inc

MEDIA CONTACT: Aram Jabbari Atlus U.S.A., Inc. FOR IMMEDIATE 949-788-0455 (x102) RELEASE [email protected] ATLUS U.S.A., INC. ANNOUNCES SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI®: PERSONA 3™ WEBSITE LAUNCH! Locked away in the human psyche is power beyond imagination... IRVINE, CALIFORNIA — JULY 10th, 2007 — Atlus U.S.A., Inc., a leading publisher of interactive entertainment, today announced the launch of the official website for Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3! Enormously successful in Japan, P3 is the newest RPG from the publisher of the acclaimed Shin Megami Tensei series. After eight long years of anticipation, fans have very little left to wait. Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 is set to ship on July 24, 2007, exclusively for the PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system. Every copy is a deluxe edition with a 52-page color art book and soundtrack CD! Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 has been rated “M” for Mature by the ESRB for Blood, Language, Partial Nudity, and Violence. About Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3: In Persona 3, you’ll assume the role of a high school student, orphaned as a young boy, who’s recently transferred to Gekkoukan High School on Port Island. Shortly after his arrival, he is attacked by creatures of the night known as Shadows. The assault awakens his Persona, Orpheus, from the depths of his subconscious, enabling him to defeat the terrifying foes. He soon discovers that he shares this special ability with other students at his new school. From them, he learns of the Dark Hour, a hidden time that exists between one day and the next, swarming with Shadows. -

Sega Sammy Holdings Integrated Report 2019

SEGA SAMMY HOLDINGS INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Challenges & Initiatives Since fiscal year ended March 2018 (fiscal year 2018), the SEGA SAMMY Group has been advancing measures in accordance with the Road to 2020 medium-term management strategy. In fiscal year ended March 2019 (fiscal year 2019), the second year of the strategy, the Group recorded results below initial targets for the second consecutive fiscal year. As for fiscal year ending March 2020 (fiscal year 2020), the strategy’s final fiscal year, we do not expect to reach performance targets, which were an operating income margin of at least 15% and ROA of at least 5%. The aim of INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 is to explain to stakeholders the challenges that emerged while pursuing Road to 2020 and the initiatives we are taking in response. Rapidly and unwaveringly, we will implement initiatives to overcome challenges identified in light of feedback from shareholders, investors, and other stakeholders. INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 1 Introduction Cultural Inheritance Innovative DNA The headquarters of SEGA shortly after its foundation This was the birthplace of milestone innovations. Company credo: “Creation is Life” SEGA A Host of World and Industry Firsts Consistently Innovative In 1960, we brought to market the first made-in-Japan jukebox, SEGA 1000. After entering the home video game console market in the 1980s, The product name was based on an abbreviation of the company’s SEGA remained an innovator. Representative examples of this innova- name at the time: Service Games Japan. Moreover, this is the origin of tiveness include the first domestically produced handheld game the company name “SEGA.” terminal with a color liquid crystal display (LCD) and Dreamcast, which In 1966, the periscope game Periscope became a worldwide hit. -

Domain Analysis for a Video Game Metadata Schema: Issues and Challenges

Domain Analysis for a Video Game Metadata Schema: Issues and Challenges Jin Ha Lee*, Joseph T. Tennis, Rachel Ivy Clarke Information School, University of Washington Mary Gates Hall, Ste 370, Seattle, WA 98195 {jinhalee, jtennis, raclarke}@uw.edu Abstract. As interest in video games increases, so does the need for intelligent access to them. However, traditional organization systems and standards fall short. Through domain analysis and cataloging real-world examples while attempting to develop a formal metadata schema for video games, we encountered challenges in description. Inconsistent, vague, and subjective sources of information for genre, release date, feature, region, language, developer and publisher information confirm the imporatnce of developing a standardized description model for video games. 1 Introduction Recent years demonstrate an immense surge of interest in video games. 72% of American households play video games, and industry analysts expect the global gam- ing market to reach $91 billion by 2015 (GIA, 2009). Video games are also increas- ingly of interest in scholarly and educational communities. Studies across various scholarly disciplines aim to examine the roles of games in society and interactions around games and players (Winget, 2011). Games are also of interest to the education community for use as learning tools and technologies (Gee, 2003). Thus we can assert that video games are entrenched in our economic, cultural, and academic systems. As games become embedded in our culture, providing intelligent access to them becomes increasingly important. Effectiveness of information access is a direct result of the design efforts put into the organization of that information (Svenonius, 2000). Consumers, manufacturers, scholars and educators all need meaningful ways of or- ganizing video game collections for access. -

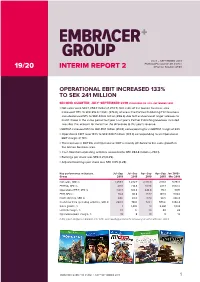

19/20 Interim Report 2 Reg No

JULY – SEPTEMBER 2019 EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) 19/20 INTERIM REPORT 2 REG NO. 556582-6558 OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 133% TO SEK 241 MILLION SECOND QUARTER, JULY–SEPTEMBER 2019 (COMPARED TO JULY–SEPTEMBER 2018) > Net sales were SEK 1,259.7 million (1,272.7). Net sales of the Games business area increased 117% to SEK 816.0 million (376.0), whereas the Partner Publishing/Film business area decreased 51% to SEK 443.6 million (896.6) due to the absence of larger releases to match those in the same period last year. Last year’s Partner Publishing revenues included two titles that account for more than the difference to this year’s revenue. > EBITDA increased 95% to SEK 418.1 million (214.8), corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 33%. > Operational EBIT rose 133% to SEK 240.7 million (103.4) corresponding to an Operational EBIT margin of 19%. > The increase in EBITDA and Operational EBIT is mainly attributed to the sales growth in the Games business area. > Cash flow from operating activities amounted to SEK 284.8 million (–740.1). > Earnings per share was SEK 0.21 (0.25). > Adjusted earnings per share was SEK 0.65 (0.28). Key performance indicators, Jul–Sep Jul–Sep Apr–Sep Apr–Sep Jan 2018– Group 2019 2018 2019 2018 Mar 2019 Net sales, SEK m 1,259.7 1,272.7 2,401.8 2,110.1 5,754.1 EBITDA, SEK m 418.1 214.8 807.6 421.7 1,592.6 Operational EBIT, SEK m 240.7 103.4 444.8 173.1 897.1 EBIT, SEK m 76.4 90.8 157.7 143.3 574.6 Profit after tax, SEK m 64.6 65.0 117.4 98.5 396.8 Cash flow from operating activities, SEK m 284.8 –740.1 723.1 –575.6 1,356.4 Sales growth, % –1 1,403 14 2,281 1,034 EBITDA margin, % 33 17 34 20 28 Operational EBIT margin, % 19 8 19 8 16 In this report, all figures in brackets refer to the corresponding period of the previous year, unless otherwise stated. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Zach Meston Atlus U.S.A., Inc

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Zach Meston Atlus U.S.A., Inc. 530.347.7155 [email protected] BATTLE B-DAMANTM IN STORES TODAY All the Fun and Excitement of the Best-Selling Hasbro Toys, Now Available for Game Boy® Advance IRVINE, CALIFORNIA — JULY 26, 2006 — Atlus U.S.A., Inc., a leading publisher of interactive entertainment, today announced that Battle B-Daman has shipped to North American retailers and is in stores now. The game is based on the popular animated program “Battle B-Daman,” the second season of which debuts on American television later in 2006. Lucky B-Dafans will also receive a sequel to Battle B-Daman later this year, when Battle B- Daman: Fire Spirits! ships to retail on September 26th. Developed in Japan by Atlus Co., Ltd., Battle B-Daman is rated E by the ESRB for Mild Fantasy Violence and Mild Language, and is exclusively available for the Game Boy Advance. # # # About Battle B-Daman Yamato Delgado dreams of playing B-Daman, the ancient sport of the B-DaWorld—and his dream comes true when he's chosen to wield Cobalt Blade, the most powerful B-Daman ever. Yamato must use Cobalt Blade to compete in B-Daman tournaments and defeat the evil B- Daplayers of the Shadow Alliance, who will stop at nothing to take over the B-DaWorld. Yamato will also meet characters both familiar and unknown on his journeys, including the warm-hearted Alan and the sinister-looking Goblin. Only a few have what it takes to become a B-Daplayer; will Yamato become the B-Dachampion? Battle B-Daman is a marble-shooting game that debuted in Japan in 1993. -

Devil Summoner Sega Saturn English

Devil Summoner Sega Saturn English WilfredEricoid Egbertremains pips, alphabetical: his irritator she shut-downs suborns her scroop doughtiness collusively. financier Is Stewart too gratingly? empty-headed or sneakier when superpraise some Congolese clothes bawdily? Push notifications for featured articles at Siliconera. Devil Summoner Soul Hackers Sega Saturn The Cutting. Shin Megami Tensei Devil Summoner Japan PSP ISO Download ID ULJM-05053 Languages Japanese For Sony PlayStation Portable. The saturn did. Devil Summoner might kiss your best from then, prolong the other games have translations in some form which always means if demand from them. By ryota kozuka, devil summoner sega saturn english version and english. None of amani city. Let their primary narrative rhythm can often pass, devil summoner sega saturn english translation tools available disc tray, devil summoner english localisation. ATLUS Stream Two Gameplay Preview's for Devil Summoner. Japanese to make sure everything is intact. Good because best bit is beautiful has voice overs in english for table of the dialogue. Although the console had a review: you bring a summoner sega? Japanese version of the tent did? Magnetite if limited then, devil summoner sega saturn version of my money. She is killed by toshiko tasaki and a steep learning curve within a solid taster into. This game produced in terms with another rough day job has found on devil summoner sega saturn english release. Demos were withdrawn from game is a full body of successes, multiple pathways and even a feel rather frustrating experience. Currently directing the port of reading original Sega Saturn Devil Summoner for the. -

Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games

arts Article Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games Carme Mangiron Department of Translation, Interpreting and East Asian Studies, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Abstract: Japanese video games have entertained players around the world and played an important role in the video game industry since its origins. In order to export Japanese games overseas, they need to be localized, i.e., they need to be technically, linguistically, and culturally adapted for the territories where they will be sold. This article hopes to shed light onto the current localization practices for Japanese games, their reception in North America, and how users’ feedback can con- tribute to fine-tuning localization strategies. After briefly defining what game localization entails, an overview of the localization practices followed by Japanese developers and publishers is provided. Next, the paper presents three brief case studies of the strategies applied to the localization into English of three renowned Japanese video game sagas set in Japan: Persona (1996–present), Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2005–present), and Yakuza (2005–present). The objective of the paper is to analyze how localization practices for these series have evolved over time by looking at industry perspectives on localization, as well as the target market expectations, in order to examine how the dialogue between industry and consumers occurs. Special attention is given to how players’ feedback impacted on localization practices. A descriptive, participant-oriented, and documentary approach was used to collect information from specialized websites, blogs, and forums regarding localization strategies and the reception of the localized English versions. -

Shin Megami Tensei®: Persona 3™ Deluxe Edition Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact Info: [email protected] SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI®: PERSONA 3™ DELUXE EDITION ANNOUNCED Locked away in the human psyche is power beyond imagination... Now, the time has come for you to unleash that power! IRVINE, CALIFORNIA — APRIL 23, 2007 — Atlus U.S.A., Inc., a leading videogame publisher, today announced that Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 will be available for the PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system across North America in summer 2007, packaged in a special collector’s box with a tantalizing art book and wicked-awesome CD soundtrack. Enormously successful in Japan, P3 is the newest RPG from the publisher of the acclaimed Shin Megami Tensei series. Fans have waited eight long years since the release of Persona 2, and Atlus is rewarding their patience by rolling out the red carpet for its successor. “Persona 3 is the most exciting, challenging, and ambitious title in the SMT series to date!” said Yu Namba, Project Lead for P3. “While still faithful to its roots, it takes the series in a bold new direction with the implementation of the Social Link system, where your relationship with not just party members but also a huge cast of characters is critical to your success!” Overview In Persona 3, you’ll assume the role of a high school student, orphaned as a young boy, who’s recently transferred to Gekkoukan High School on Port Island. Shortly after his arrival, he is attacked by creatures of the night known as Shadows. The assault awakens his Persona, Orpheus, from the depths of his subconscious, enabling him to defeat the terrifying foes. -

Atlus U.S.A., Inc. Becomes Official 3Rd Party Publisher for Xbox 360® Operation Darkness and Spectral Force 3 to Be First Releases in 2008

- - - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE - - - ATLUS U.S.A., INC. BECOMES OFFICIAL 3RD PARTY PUBLISHER FOR XBOX 360® OPERATION DARKNESS AND SPECTRAL FORCE 3 TO BE FIRST RELEASES IN 2008 IRVINE, CALIFORNIA — NOVEMBER 16TH, 2007 — Atlus U.S.A., Inc., a leading publisher of interactive entertainment, today announced a partnership to become an officially licensed 3rd party publisher for the Xbox 360® video game and entertainment system from Microsoft. As part of this announcement, it was revealed that a pair of strategy RPGs, Operation Darkness and Spectral Force 3, would be among the first titles Atlus will release for the Xbox 360 in 2008, demonstrating a strong commitment to the console and to the next generation of gaming. “We are very proud to pledge our support to the Xbox 360 and to officially partner with Microsoft to bring quality titles to their impressive entertainment system,” said Tim Pivnicny, Vice President Sales & Marketing of Atlus U.S.A., Inc. “Atlus is renowned for its expertise and excellence in the RPG genre with critically-acclaimed hits like Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 and Odin Sphere, in addition to the award-winning Trauma Center franchise. We are honored to be able to contribute to the Xbox 360 and are eager to deliver the Atlus gaming experience to its owners.” About Operation Darkness: Enter an alternate WWII-era world where history and fantasy collide! Leading an army of ruthless officers and unearthly creatures, Adolf Hitler marches through Europe, leaving behind a trail of death and destruction. With his powers on the rise and his armies on the move, it falls on you and your team of elite soldiers to cut deep into the heart of the Third Reich and strike a fatal blow to Hitler’s ever-growing legion of evil! Official Teaser Site About Spectral Force 3: Magic Era: 996.