Education and Curricular Perspectives in the Quran by Sarah Risha a Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prophets of the Quran: an Introduction (Part 1 of 2)

Prophets of the Quran: An Introduction (part 1 of 2) Description: Belief in the prophets of God is a central part of Muslim faith. Part 1 will introduce all the prophets before Prophet Muhammad, may the mercy and blessings of God be upon him, mentioned in the Muslim scripture from Adam to Abraham and his two sons. By Imam Mufti (© 2013 IslamReligion.com) Published on 22 Apr 2013 - Last modified on 25 Jun 2019 Category: Articles >Beliefs of Islam > Stories of the Prophets The Quran mentions twenty five prophets, most of whom are mentioned in the Bible as well. Who were these prophets? Where did they live? Who were they sent to? What are their names in the Quran and the Bible? And what are some of the miracles they performed? We will answer these simple questions. Before we begin, we must understand two matters: a. In Arabic two different words are used, Nabi and Rasool. A Nabi is a prophet and a Rasool is a messenger or an apostle. The two words are close in meaning for our purpose. b. There are four men mentioned in the Quran about whom Muslim scholars are uncertain whether they were prophets or not: Dhul-Qarnain (18:83), Luqman (Chapter 31), Uzair (9:30), and Tubba (44:37, 50:14). 1. Aadam or Adam is the first prophet in Islam. He is also the first human being according to traditional Islamic belief. Adam is mentioned in 25 verses and 25 times in the Quran. God created Adam with His hands and created his wife, Hawwa or Eve from Adam’s rib. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Ebook Download the Hadith

THE HADITH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bill Warner | 70 pages | 01 Dec 2010 | CSPI | 9781936659012 | English | United States The Hadith PDF Book The reports of Muhammad's and sometimes companions behavior collected by hadith compilers include details of ritual religious practice such as the five salat obligatory Islamic prayers that are not found in the Quran, but also everyday behavior such as table manners, [52] dress, [53] and posture. Hadith have been called "the backbone" of Islamic civilization , [5] and within that religion the authority of hadith as a source for religious law and moral guidance ranks second only to that of the Quran [6] which Muslims hold to be the word of God revealed to his messenger Muhammad. Categories : Hadith Islamic terminology Islamic theology Muhammad. My father bought a slave who practiced the profession of cupping. Musannaf Ibn Abi Shaybah. Main article: Criticism of Hadith. Al-Mu'jam al-Awsat. Depictions of Muhammed. Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal. Sahih Bukhari is a collection of sayings and deeds of Prophet Muhammad pbuh , also known as the sunnah. Leiden : Brill Publishers , Among the verses cited as proof that the Quran called on Muslims "to refrain from that which [Muhammad] forbade, to obey him and to accept his rulings" in addition to obeying the Quran, [50] are:. This narrative is verified by Abu Bakr who has the least narrations of the Hadith of all the companions of the prophet despite him being the companion that was with him the most. The first people to hear hadith were the companions who preserved it and then conveyed it to those after them. -

Madrasah Education System and Terrorism: Reality and Misconception

92 Madrasah Education System And Terrorism: Reality And Misconception Mohd Izzat Amsyar Mohd Arif ([email protected]) The National University of Malaysia, Bangi Nur Hartini Abdul Rahman ([email protected]) Ministry of Education, Malaysia Hisham Hanapi ([email protected]) Tunku Abdul Rahman University College, Kuala Lumpur Abstract Since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the Islamic schools known as madrasah have been of increasing interest to analysts and to officials involved in formulating U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East, Central, and Southeast Asia. Madrasah drew added attention when it became known that several Taliban leaders and Al-Qaeda members had developed radical political views at madrasah in Pakistan, some of which allegedly were built and partially financed through Saudi Arabian sources. These revelations have led to accusations that madrasah promote Islamic extremism and militancy, and are a recruiting ground for terrorism. Others maintain that most of these religious schools have been blamed unfairly for fostering anti-U.S. sentiments and argue that madrasah play an important role in countries where millions of Muslims live in poverty and the educational infrastructure is in decay. This paper aims to study a misconception of the role and functions of Islamic traditional religious schools which have been linked with the activities of terrorism. The study will be specifically focus on practice of the traditional Islamic school, which is locally called as ‘madrasah system’. Keywords: madrasah, terrorism, Islamic schools INTRODUCTION The September 11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York changed the international politics, security and law. The attacks gave rise to the new catchword of war against terrorism, which has been universally accepted as a new millennium global threat. -

Introduction the Peacemaking and Conflict Resolution Field and Islam

Introduction The Peacemaking and Conflict Resolution Field and Islam Qamar-ul Huda hat places do nonviolence and peacebuilding have in Islam? What are the challenges to mitigating violence in Muslim com- munities? What do Muslim religious and community leaders Wneed in order to reform the current debate on the uses of violence and non- violence? This book is the result of an international conference of Muslim scholars and practitioners who came together to address these questions, discussing contemporary Islam, its relation to violence and peacemaking, and the possibilities for reframing and reinterpreting methodologically the problems of violence and peacemaking in Muslim communities. © CopyrightThe subject of peacemaking by andthe conflict Endowment resolution in Muslim commu of- nities is especially timely. There are two active wars in Iraq and Afghani- thestan, United while radical IslamistStates groups threaten Institute the stability of ofPakistan, Peace Egypt, Lebanon, and other states. The futility of counteracting extremism with military force is contributing to radicalization in Muslim communities; in the past ten years, the narrative of extremism has not diminished, but is flourishing among the disillusioned youth and middle class.1 Given these challenges and others, it is vitally important to examine contemporary prin- ciples, methods, and approaches of peacemaking and conflict resolution by leading Muslim intellectuals and practitioners in the Islamic world. More specifically, the conference explored historical examples of -

Traditional and Modern Muslim Education at the Core and Periphery: Enduring Challenge

Traditional and Modern Muslim Education at the Core and Periphery: Enduring Challenge Tahir Abbas Abstract This chapter provides a general theory of the salient concerns affecting Muslims in education across the globe today, from Muslims in Muslim majority countries to Muslims as minority citizens. From concerns around resource investment in educational infrastructure to anxieties over curricula and pedagogy, matters affecting Muslims in education differ the world over, where Muslims in education can often conjure up more uncertainties than positives. The experience affects not only young children at the nucleus of the attention but also parents, teachers, education managers, as well as wider society. In rationalizing the political and sociological milieu in different societies, it emerges that the themes of religion, ethnicity, and gender are as significant as ideology, culture, and policy, but that they are set within the context of secularization, desecularization, sacralization and the re-sacralization of Islam in the public sphere. In order to generate a philosophical, spiritual, and intellectual evaluation of Muslim education across the world, this chapter synthesizes the apprehensions that are internal and exter- nal, local and global, and which affect all Muslims, minorities and majorities. Keywords Muslims • Education • Localization • Globalization • Modernity Contents Introduction ....................................................................................... 2 Education, Knowledge, and Power across the Muslim World . -

Circular-40-Quran Memorization Competition

SHANTINIKETAN INDIAN SCHOOL, DOHA-QATAR Circular No. : 40/Circular/2019-20 Date : 04.11.2019 CIRCULAR FOR CLASSES KG-I to XII Dear Parents Asslamu Alaikum, Wahdathu Tahfeez-al-Qur’an under the Ministry of Awquaf and Islamic Affairs is conducting an Inter-school Quran Memorization competition in February-2020 as per the schedule below. The Students who are interested to participate should submit the Entry Form with a photograph to Mr. Fawzan / Mrs. Badrunnisa on or before 12th November, 2019. The following are the portions for memorization. Tick () the portion that you would like to participate: Level: 1 Level: 2 (From the first part of the Qur’an) (From the last part of the Qur’an) To No of Portions Class From Surah Beginning End Beginning End Surah (Ajza’) 7 Al-Baqara Al-An’am (verse-110) Az-Zumar (verse-32) An-Nas KG Al-Fajr An-Nas 8 Al-Baqara Al-A’raf (verse-87) Ya-Sin (verse-28) An-Nas I Al-Fajr An-Nas 9 Al-Baqara Al-Anfal (verse-40) Al-Ahzab (verse-31) An-Nas 10 Al-Baqara At-Tawbah (verse-92) Al-Ankaboot (verse-46) An-Nas II Abasa An-Nas 11 Al-Baqara Hud (verse-5) An-Naml (verse-56) An-Nas 12 Al-Baqara Yusuf (verse-52) Al-Furqan (verse-21) An-Nas III Al-Jinn An-Nas 13 Al-Baqara Ibrahim Al-Mu’minun An-Nas IV At-Talaq An-Nas 14 Al-Baqara An-Nahl Al-Anbya An-Nas 15 Al-Baqara Al-Kahf (verse-74) Al-Kahf (verse-75) An-Nas V Al-Hashr An-Nas 16 Al-Baqara Taha Al-Isra An-Nas 17 Al-Baqara Al-Hajj Al-Hijr An-Nas VI Ar-Rahman An-Nas 18 Al-Baqara Al-Furqan (verse-20) Yusuf (verse-53) An-Nas VII Adh-Dhariyat An-Nas 19 Al-Baqara An-Naml (verse-55) -

Importance of Girls' Education As Right: a Legal Study from Islamic

Beijing Law Review, 2016, 7, 1-11 Published Online March 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/blr http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/blr.2016.71001 Importance of Girls’ Education as Right: A Legal Study from Islamic Approach Mohammad Saiful Islam Department of Law, International Islamic University Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh Received 16 November 2015; accepted 2 January 2016; published 5 January 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Knowledge gaining and application is a fundamental necessity for all Muslims to qualify them to believe according to the ideologies of the religion. Islam ordered acquisition and dissemination of knowledge is obligatory (fard) upon its believers, irrespective of gender. The aim of education in Islam is to produce a decent human being who is talented of delivering his duties as a servant of Allah and His vicegerent (khalīfah) on earth. This paper is an effort to examine the concept, goal and objectives of education on the view point of Islam. The aim of this article is to present and analyze the exact views of Islam regarding girls’ education from the ultimate source of Islam. These works also try to pick out the common barriers of girls’ education in Bangladesh. Keywords Education, Al Quran, Knowledge, Girls’ Education 1. Introduction Historically women have been subjected to social injustice and educational dispossession. Before advent of Is- lam Arabs has engaged to infanticide the girls’ babies and Islam frequently recognize the dignity and rights of girls. -

M. Fethullah Gülen's Understanding of Sunnah

M. FETHULLAH GÜLEN’S UNDERSTANDING OF SUNNAH Submitted by Mustafa Erdil A thesis in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Theology Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 Australia 23 JULY 2016 1 | P a g e STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics/Safety Committees (where required). Mustafa Erdil 23 JULY 2016 Signature: ABSTRACT The aim and objective of this study is to highlight the importance of and the status of hadith in Islam, as well as its relevance and reference to sunnah, the Prophetic tradition and all that this integral source of reference holds in Islam. Furthermore, hadith, in its nature, origin and historical development with its close relationship with the concept of memorisation and later recollection came about after the time of Prophet Muhammad. This study will thus explore the reasons behind the prohibition, in its initial stage, with the authorisation of recording the hadiths and its writing at another time. The private pages of hadith recordings kept by the companions will be sourced and explored as to how these pages served as prototypes for hadith compilations of later generations. -

Tawaqquf and Acceptance of Human Evolution

2 | Theological Non-Commitment (Tawaqquf) in Sunni Islam and Its Implications for Muslim Acceptance of Human Evolution Author Biography Dr. David Solomon Jalajel is a consultant with the Prince Sultan Research Institute at King Saud University and holds a PhD in Arabic and Islamic Studies from the University of the Western Cape. Formerly, he was a lecturer in Islamic theology and legal theory at the Dar al-Uloom in Cape Town, South Africa. His research interests concern how traditional approaches to Islamic theology and law relate to contemporary Muslim society. He has published Women and Leadership in Islamic Law: A Critical Survey of Classical Legal Texts (Routledge), Islam and Biological Evolution: Exploring Classical Sources and Methodologies (UWC) and Expressing I`rāb: The Presentation of Arabic Grammatical Analysis (UWC). Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2019, 2020. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Theological Non-Commitment (Tawaqquf) in Sunni Islam and Its Implications for Muslim Acceptance of Human Evolution Abstract Traditional Muslims have been resistant to the idea of human evolution, justifying their stance by the account of Adam and Eve being created without parents as traditionally understood from the apparent (ẓāhir ) meaning of the Qur’an and Sunnah. The account of the creation of these two specific individuals belongs to a category of questions that Sunni theologians refer to as the samʿiyyāt, “revealed knowledge.” These are matters for which all knowledge comes exclusively from Islam’s sacred texts. -

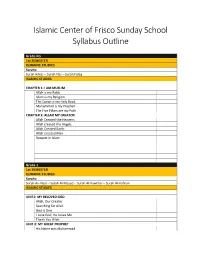

Islamic Center of Frisco Sunday School Syllabus Outline

Islamic Center of Frisco Sunday School Syllabus Outline Grade KG 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah Ikhlas – Surah Nas – Surah Falaq ISLAMIC STUDIES CHAPTER 1: I AM MUSLIM Allah is my Rabb Islam is my Religion The Quran is my Holy Book Muhammad is my Prophet The Five Pillars are my Path CHAPTER 2: ALLAH MY CREATOR Allah Created the Heavens Allah created the Angels Allah Created Earth Allah Created Man Respect in Islam Grade 1 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah An-Nasr – Surah Al-Masad - Surah Al-Kawthar – Surah Al-Kafirun ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIT1: MY BELOVED GOD Allah, Our Creator Searching for Allah God is One I Love God, He Loves Me Thank You Allah UNIT 2: MY GREAT PROPHET His Name was Muhammad Muhammad as a Child Muhammad Worked Hard The Prophet’s Family Muhammad Becomes a Prophet Sahaba: Friends of the Prophet UNIT 3: WORSHIPPING ALLAH Arkan-ul-Islam: The Five Pillars of Islam I Love Salah Wud’oo Makes me Clean Zaid Learns How to Pray UNIT 4: MY MUSLIM WORLD My Muslim Brothers and Sisters Assalam o Alaikum Eid Mubarak UNIT 5: MY MUSLIM MANNERS Allah Loves Kindness Ithaar and Caring I Obey my Parents I am a Muslim, I must be Clean A Dinner in our Neighbor’s Home Leena and Zaid Sleep Over at their Grandparents’ Home Grade 2 1st SEMESTER QURANIC STUDIES Surahs: Surah Al-Quraish – Surah Al-Maun - Surah Al-Humaza – Surah Al-Feel ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIT1: IMAN IN MY LIFE I Think of Allah First I Obey Allah: The Story of Prophet Adam (A.S) The Sons of Adam I Trust Allah: The Story of Prophet Nuh (A.S) My God is My Creator Taqwa: -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us.