Dirk Bogarde's Gamble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, It’s been really heart-warming to read all your lovely letters and emails of support about what Talking Pictures TV has meant to you during lockdown, it means so very much to us here in the projectionist’s box, thank you. So nice to feel we have helped so many of you in some small way. Spring is on the horizon, thank goodness, and hopefully better times ahead for us all! This month we are delighted to release the charming filmThe Angel Who Pawned Her Harp, the perfect tonic, starring Felix Aylmer & Diane Cilento, beautifully restored, with optional subtitles plus London locations in and around Islington such as Upper Street, Liverpool Road and the Regent’s Canal. We also have music from The Shadows, dearly missed Peter Vaughan’s brilliant book; the John Betjeman Collection for lovers of English architecture, a special DVD sale from our friends at Strawberry, British Pathé’s 1950 A Year to Remember, a special price on our box set of Together and the crossword is back! Also a brilliant book and CD set for fans of Skiffle and – (drum roll) – The Talking Pictures TV Limited Edition Baseball Cap is finally here – hand made in England! And much, much more. Talking Pictures TV continues to bring you brilliant premieres including our new Saturday Morning Pictures, 9am to 12 midday every Saturday. Other films to look forward to this month include Theirs is the Glory, 21 Days with Vivien Leigh & Laurence Olivier, Anthony Asquith’s Fanny By Gaslight, The Spanish Gardener with Dirk Bogarde, Nijinsky with Alan Bates, Woman Hater with Stewart Granger and Edwige Feuillère,Traveller’s Joy with Googie Withers, The Colour of Money with Paul Newman and Tom Cruise and Dangerous Davies, The Last Detective with Bernard Cribbins. -

My Life at Shaare Zedek

From 1906 until 1916 I was a nurse at the Salomon Heine Hospital in Hamburg. (Salomon Heine was the uncle of Heinrich Heine who wrote a poem about this hospital.) The first time that Jewish nurses sat for examinations by the German authorities and received a German State Diploma was in 1913. One of my colleagues and I were the first Jewish nurses who received a State Diploma in Germany. We both passed the examinations with “very good”, and the German doctors especially praised our theoretical and practical knowledge. In 1916, during the first world war, I left the hospital and started out on my way to the then called Palestine. I arrived in the country in December of that year. The following events influenced my decision to come here. Dr. Wallach went on a trip to Europe when the hospital urgently needed a head nurse. He inspected several hospitals and, among them, the Salomon Heine Hospital in Hamburg, which impressed him especially because its structure was similar to that of his own hospital. Dr. Wallach turned to the head nurse to ask if she could spare a nurse who would be willing to serve as head nurse for him. Four nurses of the hospital had already been put at the disposal of the State. She thought that Schwester Selma might like to serve her war service in Palestine. Dr. Wallach came to this country at the end of the 19th century, a native 5 of Cologne. His coming was prompted by sheer idealism and also by his religious attitude. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The Nature of Medicine in South Africa: the Intersection of Indigenous and Biomedicine

THE NATURE OF MEDICINE IN SOUTH AFRICA: THE INTERSECTION OF INDIGENOUS AND BIOMEDICINE By Kristina Monroe Bishop __________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY AND DEVELOPMENT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN GEOGRAPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kristina Monroe Bishop entitled The Nature of Medicine in South Africa: The Intersection of Indigenous and Biomedicine and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 Paul Robbins _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 John Paul Jones III _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 Sarah Moore _____________________________________________Date: May 7, 2010 Ivy Pike Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. ________________________________________________ Date: May 7, 2010 Dissertation Director: Paul Robbins 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrower under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted from the author. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

The Nation's Matron: Hattie Jacques and British Post-War Popular Culture

The Nation’s Matron: Hattie Jacques and British post-war popular culture Estella Tincknell Abstract: Hattie Jacques was a key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, condensing a range of contradictions around power, desire, femininity and class through her performances as a comedienne, primarily in the Carry On series of films between 1958 and 1973. Her recurrent casting as ‘Matron’ in five of the hospital-set films in the series has fixed Jacques within the British popular imagination as an archetypal figure. The contested discourses around nursing and the centrality of the NHS to British post-war politics, culture and identity, are explored here in relation to Jacques’s complex star meanings as a ‘fat woman’, ‘spinster’ and authority figure within British popular comedy broadly and the Carry On films specifically. The article argues that Jacques’s star meanings have contributed to nostalgia for a supposedly more equitable society symbolised by socialised medicine and the feminine authority of the matron. Keywords: Hattie Jacques; Matron; Carry On films; ITMA; Hancock’s Half Hour; Sykes; star persona; post-war British cinema; British popular culture; transgression; carnivalesque; comedy; femininity; nursing; class; spinster. 1 Hattie Jacques (1922 – 1980) was a gifted comedienne and actor who is now largely remembered for her roles as an overweight, strict and often lovelorn ‘battle-axe’ in the British Carry On series of low- budget comedy films between 1958 and 1973. A key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, Hattie Jacques’s star meanings are condensed around the contradictions she articulated between power, desire, femininity and class. -

Doctors in the Movies School, Right?’’ Dr Sands Replies, ‘‘What, Are You Going to Arrest Me for Failing to G Flores Live up to My Potential?’’

1084 LEADING ARTICLE Entertainment a patient due to operating while Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.2003.043232 on 19 November 2004. Downloaded from ....................................................................................... addicted to drugs, and the agent says, ‘‘This is not how a doctor lives. No, this is squalor. I mean, you did go to medical Doctors in the movies school, right?’’ Dr Sands replies, ‘‘What, are you going to arrest me for failing to G Flores live up to my potential?’’. Money is not infrequently portrayed as ................................................................................... the prime motivation for becoming a doctor and choosing a medical specialty. Healers, heels, and Hollywood In Not As a Stranger (1955), medical school classmates discuss their career options: he world continues to have a pas- MAJORTHEMESINDOCTOR sion for movies. Moviegoers world- MOVIES ‘‘Personally, I’m for surgery. I just Twide spent $20.3 billion and Money and materialism got a look at Dr Dietrich’s car. You purchased 8.6 billion admission tickets Materialism and a love of money have know what he drives? A Bentley. 1 to see films in 2003. 2002 was a record pervaded cinematic portrayals of doctors $17,000 bucks.’’ breaking year at the UK box office, with dating back to the 1920s, and continue ‘‘That guy doesn’t take out a splinter 176 million cinema admissions, £755 to be prominent in recent movies. In for less than $1000.’’ million in total box office receipts, Doctor at Sea (1956), Dr Simon Sparrow ‘‘I’ll still take ear, nose, and throat. and 369 films released.2 In the USA in (Dirk Bogarde) states, ‘‘A Rolls Royce is The common cold is still the doctor’s 2003, there were 1.6 billion cinema the ambition of almost every newly best friend.’’ admissions, $9.5 billion in box office qualified doctor. -

The Booklet That Accompanied the Exhibition, With

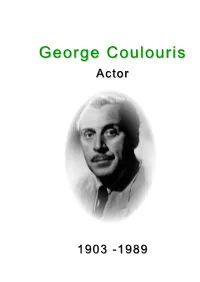

GGeeoorrggee CCoouulloouurriiss AAccttoorr 11990033 --11998899 George Coulouris - Biographical Notes 1903 1st October: born in Ordsall, son of Nicholas & Abigail Coulouris c1908 – c1910: attended a local private Dame School c1910 – 1916: attended Pendleton Grammar School on High Street c1916 – c1918: living at 137 New Park Road and father had a restaurant in Salisbury Buildings, 199 Trafford Road 1916 – 1921: attended Manchester Grammar School c1919 – c1923: father gave up the restaurant Portrait of George aged four to become a merchant with offices in Salisbury Buildings. George worked here for a while before going to drama school. During this same period the family had moved to Oakhurst, Church Road, Urmston c1923 – c1925: attended London’s Central School of Speech and Drama 1926 May: first professional stage appearance, in the Rusholme (Manchester) Repertory Theatre’s production of Outward Bound 1926 October: London debut in Henry V at the Old Vic 1929 9th Dec: Broadway debut in The Novice and the Duke 1933: First Hollywood film Christopher Bean 1937: played Mark Antony in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre production of Julius Caesar 1941: appeared in the film Citizen Kane 1950 Jan: returned to England to play Tartuffe at the Bristol Old Vic and the Lyric Hammersmith 1951: first British film Appointment With Venus 1974: played Dr Constantine to Albert Finney’s Poirot in Murder On The Orient Express. Also played Dr Roth, alongside Robert Powell, in Mahler 1989 25th April: died in Hampstead John Koulouris William Redfern m: c1861 Louisa Bailey b: 1832 Prestbury b: 1842 Macclesfield Knutsford Nicholas m: 10 Aug 1902 Abigail Redfern Mary Ann John b: c1873 Stretford b: 1864 b: c1866 b: c1861 Greece Sutton-in-Macclesfield Macclesfield Macclesfield d: 1935 d: 1926 Urmston George Alexander m: 10 May 1930 Louise Franklin (1) b: Oct 1903 New York Salford d: April 1989 d: 1976 m: 1977 Elizabeth Donaldson (2) George Franklin Mary Louise b: 1937 b: 1939 Where George Coulouris was born Above: Trafford Road with Hulton Street going off to the right. -

37 Agenda Bibliomediateca Dal 26.10 Al 01.11.2012 Ok

Agenda settimanale degli eventi in Bibliomediateca da venerdì 26 ottobre a giovedì 1 novembre 2012 Bibliomediateca “Mario Gromo” - Sala Eventi Via Matilde Serao 8/A, Torino tel. +39 011 8138 599 - email: [email protected] Sommario: 29.10 – SHAKESPEARE A HOLLYWOOD – La sottana di ferro di Ralph Thomas (ore 15.30) 30.10 – NUOVI ORIZZONTI DELLA TEORIA E DELLA STORIOGRAFIA – Il cinema italiano negli anni ’30: nuove ricerche (15.00) LUNEDI’ 29 OTTOBRE – ORE 15.30 Ultimo appuntamento della rassegna SHAKESPEARE A HOLLYWOOD con la proiezione del film La sottana di ferro di Ralph Thomas. Ultimo appuntamento della rassegna SHAKESPEARE A HOLLYWOOD. Ben Hecht sceneggiatore con la proiezione, lunedì 29 ottobre , alle ore 15.30 , nella sala eventi della Bibliomediateca, del film La sottana di ferro di Ralph Thomas. Realizzato nel 1956 da Ralph Thomas, il film fu sceneggiato in origine da Ben Hecht che aveva scelto un titolo completamente differente: Not For Money. Svariate vicissitudini produttive e l’arrivo di Bob Hope nel ruolo del co-protagonista (inizialmente assegnato a Cary Grant) causarono non pochi problemi: Hope e i suoi scrittori modificarono intere parti di sceneggiatura tagliando le maggiori scene con la Hepburn e modificando il titolo in The Iron Petticoat. Questa operazione non piacque a Hecht che decise di abbandonare il progetto rifiutandosi persino di apparire nei credits. La commedia, fortemente influenzata da Ninotchka - film del 1939 di Ernst Lubitsch - nonostante l'abbandono di Hecht, conserva, in alcune parti, il “tocco” dello sceneggiatore americano nei classici dialoghi/battibecchi tra i due protagonisti e nell'ironia con cui si prende gioco dei tipici cliché anticomunisti dell'epoca. -

Woman of Straw Ending

Woman of straw ending In Woman of Straw (), playing the calculating nephew of Ralph in the playhouses of London's West End. It's thinly populated by stock characters, yet. I can predict the ending of stuff like “Titanic. way ahead of the film “Woman of Straw,” a forgotten British thriller starring Sean Connery. Such is the situation presented with high style in Woman of Straw, up at the end to work things out, and in this case that's Alexander Knox. Crime · Tyrannical but ailing tycoon Charles Richmond becomes very fond of his attractive Italian .. Filming Locations: Audley End House, Saffron Walden, Essex, England, UK See more». IMDb > Woman of Straw () > Reviews & Ratings - IMDb Towards the end, though, his character turns sociopathically chilling, and he hits some good. That is exactly what we have in "Woman of Straw," and you can be certain that Mr. Connery did not No wonder Mr. Connery double-crosses her in the end. I think Connery's downright creepy in WOMAN OF STRAW and I wish he (when mysteries were still that)that kept you guessing until the end. Movie Review – WOMAN OF STRAW (). for this movie, and that's the ending, which came a little too fast and seemed a little too pat to be. Crafty Tony (Sean Connery) is considering whether to bring the sexy new italian nurse Maria (Gina Lollobrigida. There are no critic reviews yet for Woman of Straw. Keep checking If you can withstand the slow start the payoff at the end is well modest. Bond films to star in another fascinating suspense film, Woman of Straw. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.