COLUBER (=HIEROPHIS) Cies Introduced by Pre-Historic Man Probably 6000 Years B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Miocene-Divergent Lineage of Old World Racer Snake from India

RESEARCH ARTICLE A New Miocene-Divergent Lineage of Old World Racer Snake from India Zeeshan A. Mirza1☯*, Raju Vyas2, Harshil Patel3☯, Jaydeep Maheta4, Rajesh V. Sanap1☯ 1 National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bangalore 560065, India, 2 505, Krishnadeep Towers, Mission Road, Fatehgunj, Vadodra 390002, Gujarat, India, 3 Department of Biosciences, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat-395007, Gujarat, India, 4 Shree cultural foundation, Ahmedabad 380004, Gujarat, India ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract A distinctive early Miocene-divergent lineage of Old world racer snakes is described as a new genus and species based on three specimens collected from the western Indian state of Gujarat. Wallaceophis gen. et. gujaratenesis sp. nov. is a members of a clade of old world racers. The monotypic genus represents a distinct lineage among old world racers is recovered as a sister taxa to Lytorhynchus based on ~3047bp of combined nuclear (cmos) and mitochondrial molecular data (cytb, ND4, 12s, 16s). The snake is distinct morphologi- cally in having a unique dorsal scale reduction formula not reported from any known colubrid snake genus. Uncorrected pairwise sequence divergence for nuclear gene cmos between OPEN ACCESS Wallaceophis gen. et. gujaratenesis sp. nov. other members of the clade containing old Citation: Mirza ZA, Vyas R, Patel H, Maheta J, world racers and whip snake is 21–36%. Sanap RV (2016) A New Miocene-Divergent Lineage of Old World Racer Snake from India. PLoS ONE 11 (3): e0148380. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148380 Introduction Editor: Ulrich Joger, State Natural History Museum, GERMANY Colubrid snakes are one of the most speciose among serpents with ~1806 species distributed across the world [1–5]. -

The Amphibians and Reptiles of Cyprus Cyprus.Qxd 11/14/09 1:12 PM Page 2

Baier et al Cover_03.11.2009.qxd 17.11.2009 15:04 Seite 1 Felix Sebastian Baier. Felix Baier Born 1987 in Heidelberg, Germany. Travelling to Cyprus since his early childhood and deeply fascinated by living David J. Sparrow things, he has long been interested in the island’s nature, Hans-Jörg Wiedl especially in reptiles and amphibians. On the basis of intensive zoological reading, he conducted his first field studies while still at school. Civil service at the Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg (Frankfurt/M.) gave him the chance to bring further ideas to fruition. Since 2008, he has been studying biology and philosophy at The Amphibians the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich. David J. Sparrow. and Reptiles of Cyprus Born in 1946 in the UK. Dr. David Sparrow is a Singapore-based photographer. He gained BSc (Hons) (1964) and PhD (1970) degrees in chemistry from the University of Birmingham, England. He worked in the chemical industry for 34 years during which time he co- authored, edited, reviewed and refereed numerous sci- entific articles, papers and books. He has had a lifetime fascination with snakes, and this project gave him the opportunity to combine this interest with his passion The Amphibians of Cyprus and Reptiles for photography. Hans-Jörg Wiedl (“Snake George”). Born 1943 in Innsbruck (Austria), he grew up in the wilderness of Häselgehr in the Lechtal (Tirol), now a National Park. As an UN peacekeeper in Cyprus in 1973/1974, he developed his deep concern for the conservation of the herpetofauna of Cyprus. In 1986, he moved permanently to Cyprus, and established the “Snake George Reptile Park” in 1995. -

Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae) in the Aegean Island of Tsougriá, Northern Sporades, Greece

Biodiversity Journal , 2013, 4 (4): 553-556 Fi rst record of Hierophis gemonensis (Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae) in the Aegean island of Tsougriá, Northern Sporades, Greece Mauro Grano¹ *, Cristina Cattaneo² & Augusto Cattaneo³ ¹ Via Valcenischia 24 – 00141 Roma, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] ² Via Eleonora d’Arborea 12 – 00162 Roma, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] ³ Via Cola di Rienzo 162 – 00192 Roma, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author ABSTRACT The presence of Hierophis gemonensis (Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae) in Tsougriá, a small island of the Northern Sporades, Greece, is here recorded for the first time. KEY WORDS Aegean islands; Balkan whip snake; Hierophis gemonensis ; Northern Sporades; Tsougriá. Received 05.11.2013; accepted 02.12.2013; printed 30.12.2013 INTRODUCTION Psili: Clark, 1973, 1989; Kock, 1979. Tolon: Clark, 1973, 1989; Kock, 1979. The Balkan whip snake, Hierophis gemonensis Stavronissos, Dhokos, Trikkeri (archipelago of (Laurenti, 1768) (Reptilia Serpentes Colubridae), is Hydra): Clark, 1989. widespread along the coastal areas of Slovenia, Kythera: Boulenger, 1893; Kock, 1979. Croatia, Bosnia-Erzegovina, Montenegro, Albania Crete: Boettger, 1888; Sowig, 1985. and Greece (Vanni et al., 2011). The basic colour is Cretan islets silver gray to dark green with some spots only on Gramvoussa: Wettstein, 1953; Kock, 1979. one third of the body, tending to regular stripes on Gavdos: Wettstein, 1953; Kock, 1979. the tail. Melanistic specimens are also known Gianyssada: Wettstein, 1953; Kock, 1979. (Dimitropoulos, 1986; Schimmenti & Fabris, Dia: Raulin, 1869; Kock, 1979. 2000). The total length is usually less than 130 cm, Theodori: Wettstein, 1953. with males larger than females (Vanni et al., 2011). -

Trophic Niche Overlap in Two Syntopic Colubrid Snakes (Hierophis Viridiflavus and Zamenis Longissimus) with Contrasted Lifestyle

Amphibia-Reptilia 33 (2012): 37-44 Trophic niche overlap in two syntopic colubrid snakes (Hierophis viridiflavus and Zamenis longissimus) with contrasted lifestyles Hervé Lelièvre1,2,∗, Pierre Legagneux3, Gabriel Blouin-Demers4, Xavier Bonnet1, Olivier Lourdais1 Abstract. In many organisms, including snakes, trophic niche partitioning is an important mechanism promoting species coexistence. In ectotherms, feeding strategies are also influenced by lifestyle and thermoregulatory requirements: active foragers tend to maintain high body temperatures, expend more energy, and thus necessitate higher energy income. We studied diet composition and trophic niche overlap in two south European snakes (Hierophis viridiflavus and Zamenis longissimus) in the northern part of their range. The two species exhibit contrasted thermal adaptations, one being highly mobile and thermophilic (H. viridiflavus) and the other being elusive with low thermal needs (Z. longissimus). We analyzed feeding rate (proportion of snakes with indication of a recent meal) and examined more than 300 food items (fecal pellets and stomach contents) in 147 Z. longissimus and 167 H. viridiflavus. There was noticeable overlap in diet (overlap of Z. longissimus on H. viridiflavus = 0.62; overlap of H. viridiflavus on Z. longissimus = 0.80), but the similarity analyses showed some divergence in diet composition. Dietary spectrum was wider in H. viridiflavus, which fed on various mammals, birds, reptiles, and arthropods whereas Z. longissimus was more specialized on mammals and birds. The more generalist nature of H. viridiflavus was consistent with its higher energy requirements. In contrast to our expectation, feeding rate was apparently higher in Z. longissimus than in H. viridiflavus, but this could be an artifact of a longer transit time in Z. -

2008 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Le Centre Sheraton Montréal Hotel Montréal, Quebec, Canada 23 July 2008 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University Biological Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - OE 167 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 31 May 2008 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 23 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Salon A&B in the Le Centre Sheraton, Montréal Hotel. President Mushinsky plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book. Items that a governor wishes to discuss will be exempted from the motion for blanket acceptance and will be acted upon individually. We will cover the proposed consititutional changes following discussion of reports. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Montreal. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Montréal on 20 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive late on the afternoon of 22 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 27 July 2005 from 1800-2000 h in Salon A&C. Please plan to attend the BOG meeting and Annual Business Meeting. I look forward to seeing you in Montréal. Sincerely, Maureen A. Donnelly ASIH Secretary 1 ASIH BOARD OF GOVERNORS 2008 Past Presidents Executive Elected Officers Committee (not on EXEC) Atz, J.W. -

Herpetological Journal FULL PAPER

Volume 31 (July 2021), 142-150 Herpetological Journal FULL PAPER https://doi.org/10.33256/31.3.142150 Published by the British Repeated use of high risk nesting areas in the European Herpetological Society whip snake, Hierophis viridiflavus Xavier Bonnet1, Jean-Marie Ballouard2, Gopal Billy1 & Roger Meek3 1 CEBC, UMR-7372, CNRS-Université de La Rochelle, Villiers en Bois, France 2 Centre for Research and Conservation of Chelonians, SOPTOM, Gonfaron, France 3 Institute for Development, Ecology, Conservation and Cooperation, Rome, Italy Oviparous snakes deposit their egg clutches in sites sheltered from predation and from strong thermal and hydric fluctuations. Appropriate laying sites with optimum thermal and hydric conditions are generally scarce and are not necessarily localised in the home range. Thus, many gravid females undertake extensive trips for oviposition, and many may converge at the best egg laying sites. Dispersal mortality of neonates post-hatchling is also a critical factor. Assessing the parameters involved in this intergenerational trade-off is difficult however, and no study has succeeded in embracing all of them. Here we report data indicating that gravid females of the highly mobile European whip snake, Hierophis viridiflavus exhibit nest site fidelity whereby they repeatedly deposit their eggs in cavities under sealed roads over many decades. These anthropogenic structures provide benefits of relative safety and suitable incubation conditions (due to the protective asphalted layer?), but they expose both females and neonates to high risk of road mortality. Artificial laying sites constructed at appropriate distances from busy roads, along with artificial continuous well protected pathways (e.g. dense hedges) that connect risky laying sites to safer areas, should be constructed. -

Delineating Metrics of Diversity for a Snake Community in a Rare Ecosystem

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Delineating Metrics of Diversity for a Snake Community in a Rare Ecosystem Zachary John Marcou [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds Part of the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Marcou, Zachary John, "Delineating Metrics of Diversity for a Snake Community in a Rare Ecosystem" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 200. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/200 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Delineating Metrics of Diversity for a Snake Community in a Rare Ecosystem Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This thesis is available at SFA ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/200 DELINEATING METRICS OF DIVERSITY FOR A SNAKE COMMUNITY IN A RARE ECOSYSTEM By ZACHARY JOHN MARCOU, Bachelor of Science Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Stephen F. Austin State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science STEPHEN F. AUSTIN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2018 DELINEATING METRICS OF DIVERSITY FOR A SNAKE COMMUNITY IN A RARE ECOSYSTEM By ZACHARY JOHN MARCOU, Bachelor of Science APPROVED: ____________________________________________ Stephen J. Mullin, Ph.D., Thesis Director ____________________________________________ Matthew A. Kwiatkowski, Ph.D., Committee Member ____________________________________________ D. -

The Ecology of the Western Whip Snake, Coluber Viridiflavus (Lacépède, 1789), in Mediterranean Central Italy (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 1997 Band/Volume: 10_1_2 Autor(en)/Author(s): Capula Massimo, Filippi Ernesto, Luiselli Luca M., Trujillo Jesus Veronica Artikel/Article: The ecology of the Western Whip Snake, Coluber viridiflavus (Lacépède, 1789), in Mediterranean Central Italy (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae). 65-79 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA 10 (1/2): 65 - 79 Wien, 30. Juli 1997 The ecology of the Western Whip Snake, Coluber viridiflavus (LACÉPÈDE, 1789), in Mediterranean Central Italy (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae) Ökologie der Gelbgrünen Zornnatter, Coluber viridiflavus (LACÉPÈDE, 1789), im mediterranen Mittelitalien (Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae) MASSIMO CAPULA & ERNESTO FILIPPI & LUCA LUISELLI & VERONICA TRUJHXO JESUS KURZFASSUNG Der englische Sammelbegriff "Whip Snakes" [Peitschennattern, Zomnattem] bezeichnet phylogenetisch nicht näher verwancfte Schlangen (Colubridae und Elapidae), die durch bemerkenswerte Konvergenzen in verschiedenen morphologischen, ökologischen und ethologischen Merkmalsausprägungen einander ähnlich sind. Nach SHINE (1980), entwickelten sie diese Merkmalsausprägungen zur Ermöglichung einer erfolgreichen Jagd auf flinke, tagaktive Beutet- iere, mehrheitlich Eidechsen. Im mediterranen Mittelitalien (Tolfa Berge, Provinz Rom) untersuchten wir die Ökologie der Gelbgünen Zorn- natter -

Hierophis Viridiflavus

Hierophis viridiflavus Region: 3 Taxonomic Authority: (Lacépède, 1789) Synonyms: Common Names: Hierophis gyarosensis (Mertens, 1968) Western Whip Snake English Green Whip Snake English Gelbgrüne Zornnatter German Culebra Verdiamarilla Spanish biacco Italian Order: Ophidia Family: Colubridae Notes on taxonomy: This species was formerly included in the genus Coluber, but is included here in Hierophis following Schätti and Utiger (2001) and Nagy et al. (2004). Nagy et al. (2002) showed that the subspecies H. viridiflavus carbonarius is probably a different evolutionary unit from H.v. viridiflavus. The synonym Hierophis gyarosensis (known only from the island of Gyaros (Greece)) is actually a translocation of H.v. carbonarius (Schätti, in press). General Information Biome Terrestrial Freshwater Marine Geographic Range of species: Habitat and Ecology Information: This species ranges from northeastern Spain; western, southern, It is found in dry, open, well vegetated habitats. It occurs in scrubland, eastern and northeastern France; and southern Switzerland, through macchia, open woodland (deciduous and mixed), heathland, cultivated most of Italy, to southwestern Slovenia and northern Croatia. It is areas, dry river beds, rural gardens, roads, stone walls and ruins. The present on the Mediterranean islands of Corsica (France), Sardinia, species lays four to 15 eggs. Sicily and most other Italian islands, Krk (Croatia), and Malta. The species may occur in Luxembourg, but this requires verification. The species is absent from Austria. It has also been translocated to the island of Gyaros (Greece) in the Aegean Sea where it was described as a new species but it is now considered to be a synonym. It ranges from sea level up to 2,000m asl. -

Hierophis Gemonensis

Hierophis gemonensis Region: 8 Taxonomic Authority: (Laurenti, 1768) Synonyms: Common Names: Balkan Whip Snake English Balkan-Zornnatter German Order: Ophidia Family: Colubridae Notes on taxonomy: This species was formerly included in the genus Coluber, but is included here in Hierophis following Schätti and Utiger (2001) and Nagy et al. (2004). General Information Biome Terrestrial Freshwater Marine Geographic Range of species: Habitat and Ecology Information: This species ranges from Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, This species occurs in dry, stony areas, scrubland, macchia, open Serbia and Montenegro (Montenegro only), Albania (mostly lowlands) woodland, vineyards, olive groves, generally overgrown areas, rural and western and southern Greece. It is present on a number of islands gardens and ruins. The females lay clutches of four to 10 eggs. in the Adriatic Sea, and is present on both the Ionian Islands and the islands of Euboa, Kythera, Crete (and adjacent islets) and Karpathos of Greece. The species may be present in extreme northeastern Italy, although records from this area need to be confirmed (Claudia Corti pers. comm.). This species ranges from sea level to 1,400 m asl. Conservation Measures: Threats: It is listed on Annex III of the Bern Convention, and is present in many It is locally threatened in parts of it range by habitat loss to agricultural protected areas. No further conservation measures are immediately intensification, fire and pollution. However, in general there appear to needed for this species. be no major -

Review Species List of the European Herpetofauna – 2020 Update by the Taxonomic Committee of the Societas Europaea Herpetologi

Amphibia-Reptilia 41 (2020): 139-189 brill.com/amre Review Species list of the European herpetofauna – 2020 update by the Taxonomic Committee of the Societas Europaea Herpetologica Jeroen Speybroeck1,∗, Wouter Beukema2, Christophe Dufresnes3, Uwe Fritz4, Daniel Jablonski5, Petros Lymberakis6, Iñigo Martínez-Solano7, Edoardo Razzetti8, Melita Vamberger4, Miguel Vences9, Judit Vörös10, Pierre-André Crochet11 Abstract. The last species list of the European herpetofauna was published by Speybroeck, Beukema and Crochet (2010). In the meantime, ongoing research led to numerous taxonomic changes, including the discovery of new species-level lineages as well as reclassifications at genus level, requiring significant changes to this list. As of 2019, a new Taxonomic Committee was established as an official entity within the European Herpetological Society, Societas Europaea Herpetologica (SEH). Twelve members from nine European countries reviewed, discussed and voted on recent taxonomic research on a case-by-case basis. Accepted changes led to critical compilation of a new species list, which is hereby presented and discussed. According to our list, 301 species (95 amphibians, 15 chelonians, including six species of sea turtles, and 191 squamates) occur within our expanded geographical definition of Europe. The list includes 14 non-native species (three amphibians, one chelonian, and ten squamates). Keywords: Amphibia, amphibians, Europe, reptiles, Reptilia, taxonomy, updated species list. Introduction 1 - Research Institute for Nature and Forest, Havenlaan 88 Speybroeck, Beukema and Crochet (2010) bus 73, 1000 Brussel, Belgium (SBC2010, hereafter) provided an annotated 2 - Wildlife Health Ghent, Department of Pathology, Bacteriology and Avian Diseases, Ghent University, species list for the European amphibians and Salisburylaan 133, 9820 Merelbeke, Belgium non-avian reptiles. -

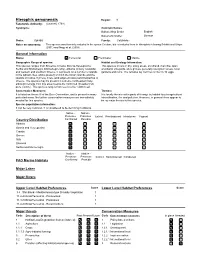

Hierophis Cypriensis

Hierophis cypriensis Region: 8 Taxonomic Authority: (Schätti, 1985) Synonyms: Common Names: Cyprus Whip Snake English Zypern-Schlanknatter English Order: Ophidia Family: Colubridae Notes on taxonomy: This species is included in Hierophis following Utiger and Schätti (2004). General Information Biome Terrestrial Freshwater Marine Geographic Range of species: Habitat and Ecology Information: This species is limited to the Troodos massif and foothills of western This snake can be found in humid areas with dense bushes, close to Cyprus. It ranges from around 500 to 1,400m asl. water or within forests. Irregularly feeds on amphibians, and may be found close to dams and similar areas where prey are often more abundant. Conservation Measures: Threats: Much of its range is within a State Forest protected area. There is It is generally threatened by persecution by local people and tourists, some public education through a local snake park. and through ongoing logging of forest habitat in the Troodos Mountains. Species population information: It is an uncommon species. Native - Native - Presence Presence Extinct Reintroduced Introduced Vagrant Country Distribution Confirmed Possible CyprusCountry: Native - Native - Presence Presence Extinct Reintroduced Introduced FAO Marine Habitats Confirmed Possible Major Lakes Major Rivers Upper Level Habitat Preferences Score Lower Level Habitat Preferences Score 1.4 Forest - Temperate 1 3.8 Shrubland - Mediterranean-type Shrubby Vegetation 1 5.7 Wetlands (inland) - Permanent Freshwater Marshes/Pools 1 (under