Challenges in Better Co-Ordinating Tokyo's Urban Rail Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

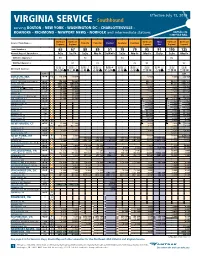

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

East Japan Railway Company Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 For the year ended March 31, 2017 Pursuing We have been pursuing initiatives in light of the Group Philosophy since 1987. Annual Report 2017 1 Tokyo 1988 2002 We have been pursuing our Eternal Mission while broadening our Unlimited Potential. 1988* 2002 Operating Revenues Operating Revenues ¥1,565.7 ¥2,543.3 billion billion Operating Revenues Operating Income Operating Income Operating Income ¥307.3 ¥316.3 billion billion Transportation (“Railway” in FY1988) 2017 Other Operations (in FY1988) Retail & Services (“Station Space Utilization” in FY2002–2017) Real Estate & Hotels * Fiscal 1988 figures are nonconsolidated. (“Shopping Centers & Office Buildings” in FY2002–2017) Others (in FY2002–2017) Further, other operations include bus services. April 1987 July 1992 March 1997 November 2001 February 2002 March 2004 Establishment of Launch of the Launch of the Akita Launch of Launch of the Station Start of Suica JR East Yamagata Shinkansen Shinkansen Suica Renaissance program with electronic money Tsubasa service Komachi service the opening of atré Ueno service 2 East Japan Railway Company Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto Shin-Aomori 2017 Hachinohe Operating Revenues ¥2,880.8 billion Akita Morioka Operating Income ¥466.3 billion Shinjo Yamagata Sendai Niigata Fukushima Koriyama Joetsumyoko Shinkansen (JR East) Echigo-Yuzawa Conventional Lines (Kanto Area Network) Conventional Lines (Other Network) Toyama Nagano BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) Lines Kanazawa Utsunomiya Shinkansen (Other JR Companies) Takasaki Mito Shinkansen (Under Construction) (As of June 2017) Karuizawa Omiya Tokyo Narita Airport Hachioji Chiba 2017Yokohama Transportation Retail & Services Real Estate & Hotels Others Railway Business, Bus Services, Retail Sales, Restaurant Operations, Shopping Center Operations, IT & Suica business such as the Cleaning Services, Railcar Advertising & Publicity, etc. -

Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's

SERVICE DELIVERY TO INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN SOUTH ASIA’S MEGA CITIES The Role of State and Non‐State Actors By Faisal Haq Shaheen H.B.Sc. (University of Toronto, 1995), M.B.A. (York University, 1997), M.A. (Ryerson University, 2009) a Dissertation presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the program of Policy Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Faisal Haq Shaheen 2017 i Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Service Delivery to Informal Settlements in South Asia's Mega Cities, the Role of State and Non‐State Actors, Ph.D., 2017, Faisal Haq Shaheen, Policy Studies, Ryerson University Abstract This interdisciplinary research project compares service delivery outcomes to informal settlements in South Asia’s largest urban centres: Dhaka, Karachi and Mumbai. These mega cities have been overwhelmed by increasing demands on limited service delivery capacity as growing clusters of informal settlements, home to significant numbers of informal sector workers, struggle to obtain basic services. -

Pdf/Rosen Eng.Pdf Rice fields) Connnecting Otsuki to Mt.Fuji and Kawaguchiko

Iizaka Onsen Yonesaka Line Yonesaka Yamagata Shinkansen TOKYO & AROUND TOKYO Ōu Line Iizakaonsen Local area sightseeing recommendations 1 Awashima Port Sado Gold Mine Iyoboya Salmon Fukushima Ryotsu Port Museum Transportation Welcome to Fukushima Niigata Tochigi Akadomari Port Abukuma Express ❶ ❷ ❸ Murakami Takayu Onsen JAPAN Tarai-bune (tub boat) Experience Fukushima Ogi Port Iwafune Port Mt.Azumakofuji Hanamiyama Sakamachi Tuchiyu Onsen Fukushima City Fruit picking Gran Deco Snow Resort Bandai-Azuma TTOOKKYYOO information Niigata Port Skyline Itoigawa UNESCO Global Geopark Oiran Dochu Courtesan Procession Urabandai Teradomari Port Goshiki-numa Ponds Dake Onsen Marine Dream Nou Yahiko Niigata & Kitakata ramen Kasumigajo & Furumachi Geigi Airport Urabandai Highland Ibaraki Gunma ❹ ❺ Airport Limousine Bus Kitakata Park Naoetsu Port Echigo Line Hakushin Line Bandai Bunsui Yoshida Shibata Aizu-Wakamatsu Inawashiro Yahiko Line Niigata Atami Ban-etsu- Onsen Nishi-Wakamatsu West Line Nagaoka Railway Aizu Nō Naoetsu Saigata Kashiwazaki Tsukioka Lake Itoigawa Sanjo Firework Show Uetsu Line Onsen Inawashiro AARROOUUNNDD Shoun Sanso Garden Tsubamesanjō Blacksmith Niitsu Takada Takada Park Nishikigoi no sato Jōetsu Higashiyama Kamou Terraced Rice Paddies Shinkansen Dojo Ashinomaki-Onsen Takashiba Ouchi-juku Onsen Tōhoku Line Myoko Kogen Hokuhoku Line Shin-etsu Line Nagaoka Higashi- Sanjō Ban-etsu-West Line Deko Residence Tsuruga-jo Jōetsumyōkō Onsen Village Shin-etsu Yunokami-Onsen Railway Echigo TOKImeki Line Hokkaid T Kōriyama Funehiki Hokuriku -

Page 1 of 8 PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Emai

PHILIP G. CRAIG 204 FERNWOOD AVENUE UPPER MONTCLAIR, NEW JERSEY 07043-1905 USA Mobile/Cell: (001) 973-787-4642 Email: [email protected] RESUME Summary Phil Craig has 50 years of experience in the rail transit and railroad field. My expertise is in planning, design, construction, and operation of heavy rail rapid transit systems (metros or subways), light rail transit systems, suburban or regional (commuter) rail systems, high-speed passenger railways, and main line passenger and freight railroads. My broad technical knowledge as a transportation planner and analyst encompasses a wide range of planning, operations, and management areas. I have held significant management positions with transport organizations serving large metropolitan areas in the United States, Great Britain and Greece, as well having been a consultant on rail projects in Canada, India, South Korea, Taiwan and Turkey. Education Bachelor of Science (Cum Laude), Public Utilities and Transportation, New York University, New York, New York, 1963 Professional Data Past Chairman (1973-76) and Committee Member (1972-80), Subcommittee on Federal Rules and Regulations Committee on Mobility for the Elderly and Handicapped American Public Transit Association, Washington, D.C., USA Member, Light Rail Transit Association, London, England Member, Light Rail Panel, New Jersey Association of Railroad Passengers Experience Independent Transportation Consultant – March 2009 to July 2009 Project: Honolulu High Capacity Transit Corridor Project, Honolulu, O'ahu, Hawai'i Clients: Kamehameha Schools and Honolulu Chapter of American Institute of Architects Assignment: Analyze Potential for Use of Light Rail Transit Technology Roles: Consultant to Kamehameha Schools and Adviser to AIA Honolulu Prepared a Light Rail Transit Feasibility Report for Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate (the largest private landholder in the Hawaiian Islands). -

Railway Lines in Tokyo and Its Suburbs

Minami-Sakurai Hasuta Shin-Shiraoka Fujino-Ushijima Shimizu-Koen Railway Lines in Tokyo and its Suburbs Higashi-Omiya Shiraoka Kuki Kasukabe Kawama Nanakodai Yagisaki Obukuro Koshigaya Atago Noda-Shi Umesato Unga Edogawadai Hatsuisi Toyoshiki Fukiage Kita-Konosu JR Takasaki Line Okegawa Ageo Ichinowari Nanasato Iwatsuki Higashi-Iwatsuki Toyoharu Takesato Sengendai Kita-Koshigaya Minami-Koshigaya Owada Tobu-Noda Line Kita-Kogane Kashiwa Abiko Kumagaya Gyoda Konosu Kitamoto Kitaageo Tobu Nota Line Toro Omiya-Koen Tennodai Miyahara Higashi-Urawa Higashi-Kawaguchi JR Musashino Line Misato Minami-Nagareyama Urawa Shin-Koshigaya Minami- Kita- Saitama- JR Tohoku HonsenKita-Omiya Warabi Nishi-Kawaguchi Kawaguchi Kashiwa Kashiwa Hon-Kawagoe Matsudo Shin- Gamo Takenozuka Yoshikawa Shin-Misato Shintoshin Nishi-Arai Umejima Mabashi Minoridai Gotanno Yono Kita-Urawa Minami-Urawa Kita-Akabane Akabane Shinden Yatsuka Shin- Musashiranzan Higashi-Jujo Kita-Matsudo Shinrin-koenHigashi-MatsuyamaTakasaka Omiya Kashiwa Toride Yono Minami- Honmachi Yono- Matsubara-Danchi Shin-Itabashi Minami-FuruyaJR Kawagoe Line Musashishi-Urawa Kita-Toda Toda Toda-Koen Ukima-Funato Kosuge JR Saikyo Line Shimo Matsudo Kita-Sakado Kita- Shimura- Akabane-Iwabuchi Soka Masuo Ogawamachi Naka-Urawa Takashimadaira Shiden Matsudo- Yono Nishi-Takashimadaira Hasune Sanchome Itabashi-Honcho Oji Kita-senju Kami- Myogaku Sashiogi Nisshin Nishi-Urawa Daishimae Tobu Isesaki Line Kita-Ayase Kanamachi Hongo Shimura- Jujo Oji-Kamiya Oku Sakasai Yabashira Kawagoe Shingashi Fujimino Tsuruse -

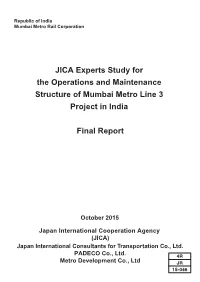

JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure Of

Republic of India Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation JICA Experts Study for the Operations and Maintenance Structure of Mumbai Metro Line 3 Project in India Final Report October 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Japan International Consultants for Transportation Co., Ltd. PADECO Co., Ltd. 4R Metro Development Co., Ltd JR 15-046 Table of Contents Chapter 1 General issues for the management of urban railways .............................. 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Management of urban railways ........................................................................................ 4 1.3 Construction of urban railways ...................................................................................... 12 1.4 Governing Structure ........................................................................................................ 17 1.5 Business Model ................................................................................................................. 21 Chapter 2 Present situation in metro projects ............................................................ 23 2.1 General .............................................................................................................................. 23 2.2 Metro projects in the world ............................................................................................. 23 2.3 Summary........................................................................................................................ -

ESCAP PPP Case Study #4

Public-Private Partnerships Case Study #4 Land Value Capture Mechanism: The Case of the Hong Kong MTR by Mathieu Verougstraete and Han Zeng (July 2014) This case study presents how a property development programme has been used to finance Hong Kong’s public transport system and discusses whether this model is replicable in other countries. LAND VALUE CAPTURE MECHANISM includes railways, trams, buses, minibuses, taxis and ferries.2 More than 90 per cent of Land value capture mechanisms follow the all motorized trips are by public transport, the 3 basic logic that enhanced accessibility to highest market share in the world. attractive and efficient transport systems adds value to land and real estate. To achieve these impressive results, major investments had to be made in public This value addition has been confirmed by transport systems. A key actor in the sector several researches. For example, research has been the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway indicates that housing price premiums in Corporation (MTRC), established in 1975 to Hong Kong are in the range of 5 to 17 per provide metro services. Its entire system now cent for units in proximity to a railway. This stretches 218.2 km and has 84 stations and premium can even exceed 30 per cent if 68 light rail stops. properties incorporate transit-oriented design, such as structures that facilitate pedestrian The sections below will describe how MTRC access to commercial amenities or provide has managed to mobilize siginificant financial pathways that are connected with stations.1 resources for its network development. As this value premium results from public MTRC BUSINESS MODEL investments, it is reasonable for public authorities to try to capture the surplus. -

Air-Rail Links in Japan 35 Years Old and Healthier Than Ever Ryosuke Hirota

Feature Railways and Air Transport Air-Rail Links in Japan 35 Years Old and Healthier than Ever Ryosuke Hirota tic and 860,000 international passengers. grown. Three airports: Haneda, Narita, Air-Rail Links in Japan Today In the same year, the monorail carried and Kansai International, each have two about 2.74 million people, including ARLs, using mostly conventional tracks During 1998, in many different parts of some non-flying passengers who used it (urban/suburban heavy rail, subways, or the world, getting to the airport became as a transit system. In 1978, airline traffic main line railways), while Haneda and easier due to construction of new air-rail in Japan grew to such an extent that a new Itami use monorails as one of their ARLs. links (ARLs). Three airports: Hong Kong airport serving Tokyo was opened for in- Japan was the first country to build a high- International Airport at Chek Lap Kok, ternational flights. This was the New To- speed train (the shinkansen), but the Copenhagen Airport at Kastrup, and Oslo kyo International Airport at Narita. honour of having the first high-speed train International Airport at Gardermoen, Haneda basically became Tokyo’s domes- serving an airport went to France when opened their first ARLs, while two other tic airport, but passenger traffic for both its TGV began linking Charles de Gaulle airports: London Heathrow and Haneda the airport and monorail continued to Airport to Paris. Unlike Frankfurt Airport Airport in Tokyo each gained a second rail grow. According to the ACI (Airports in Germany, Japan has no plans to bring link. -

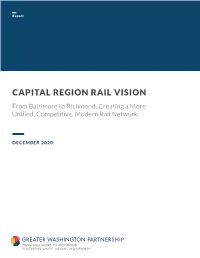

CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION from Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network

Report CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION From Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXISTING REGIONAL RAIL NETWORK 10 THE VISION 26 BIDIRECTIONAL RUN-THROUGH SERVICE 28 EXPANDED SERVICE 29 SEAMLESS RIDER EXPERIENCE 30 SUPERIOR OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION 30 CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAM 31 VISION ANALYSIS 32 IMPLEMENTATION AND NEXT STEPS 47 KEY STAKEHOLDER IMPLEMENTATION ROLES 48 NEXT STEPS 51 APPENDICES 55 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The decisions that we as a region make in the next five years will determine whether a more coordinated, integrated regional rail network continues as a viable possibility or remains a missed opportunity. The Capital Region’s economic and global Railway Express (VRE) and Amtrak—leaves us far from CAPITAL REGION RAIL NETWORK competitiveness hinges on the ability for residents of all incomes to have easy and Perryville Martinsburg reliable access to superb transit—a key factor Baltimore Frederick Penn Station in attracting and retaining talent pre- and Camden post-pandemic, as well as employers’ location Yards decisions. While expansive, the regional rail network represents an untapped resource. Washington The Capital Region Rail Vision charts a course Union Station to transform the regional rail network into a globally competitive asset that enables a more Broad Run / Airport inclusive and equitable region where all can be proud to live, work, grow a family and build a business. Spotsylvania to Richmond Main Street Station Relative to most domestic peer regions, our rail network is superior in terms of both distance covered and scope of service, with over 335 total miles of rail lines1 and more world-class service. -

Tokyo Metoropolitan Area Railway and Subway Route

NikkNikkō Line NikkNikkō Kuroiso Iwaki Tōbu-nikbu-nikkkō Niigata Area Shimo-imaichi ★ ★ Tōbu-utsunomiya Shin-fujiwara Shibata Shin-tochigi Utsunomiya Line Nasushiobara Mito Uetsu Line Network Map Hōshakuji Utsunomiya Line SAITAMA Tōhoku Shinkansen Utsunomiya Tomobe Ban-etsu- Hakushin Line Hakushin Line Niitsu WestW Line ■Areas where Suica・PASMO can be used RAILWAY Tochigi Oyama Shimodate Mito Line Niigata est Line Shinkansen Moriya Tsukuba Jōmō- Jōetsu Minakami Jōetsu Akagi Kuzū Kōgen ★ Shibukawa Line Shim-Maebashi Ryōmō Line Isesaki Sano Ryōmō Line Hokuriku Kurihashi Minami- ban Line Takasaki Kuragano Nagareyama Gosen Shinkansen(via Nagano) Takasaki Line Minami- Musashino Line NagareyamaNagareyama-- ō KukiKuki J Ōta Tōbu- TOBU Koshigaya ōōtakanomoritakanomori Line Echigo Jōetsu ShinkansenShinkansen Shin-etsu Line Line Annakaharuna Shin-etsu Line Nishi-koizumi Tatebayashi dōbutsu-kōen Kasukabe Shin-etsu Line Yokokawa Kumagaya Higashi-kHigashi-koizumioizumi Tsubamesanjō Higashi- Ogawamachi Sakado Shin- Daishimae Nishiarai Sanuki SanjSanjōō Urawa-Misono koshigaya Kashiwa Abiko Yahiko Minumadai- Line Uchijuku Ōmiya Akabane- Nippori-toneri Liner Ryūgasaki Nagaoka Kawagoeshi Hon-Kawagoe Higashi- iwabuchi Kumanomae shinsuikoen Toride Yorii Ogose Kawaguchi Machiya Kita-ayase TSUKUBA Yahiko Yoshida HachikHachikō Line Kawagoe Line Kawagoe ★ ★ NEW SHUTTLE Komagawa Keihin-Tōhoku Line Ōji Minami-Senju EXPRESS Shim- Shinkansen Ayase Kanamachi Matsudo ★ Seibu- Minami- Sendai Area Higashi-HanHigashi-Hannnō Nishi- Musashino Line Musashi-Urawa Akabane -

Railway and Area Development in Thailand 一般財団法人運輸総合研究所 タイにおける鉄道整備と沿線開発に関する国際セミナー Railway and Area Development

14 January 2020 JTTRI International Seminar on Railway and Area Development in Thailand 一般財団法人運輸総合研究所 タイにおける鉄道整備と沿線開発に関する国際セミナー Railway and Area Development Masai MUTO, Dr. Japan Transport and Tourism Research Institute Senior Research Fellow 運輸総合研究所 主任研究員 武藤 雅威 (C) Mr. MUTO Masai, Japan Transport and Tourism Research Institute, 2020 1 Profile Masai MUTO M.Eng., Department of Civil Engineering, Tokyo 1989 University of Science R&D of Superconducting Maglev Train System, 1989 Railway Technical Research Institute D.Eng., Department of Civil Engineering, Tokyo 2001 University of Science Laboratory Head of Transport Planning, 2005 Railway Technical Research Institute General Manager, Strategic Research Division 2013 Railway Technical Research Institute 2010-2019 Part-Time Lecturer, Keio University 2013-2018 Visiting Professor, Tokyo University of Science 2019 JTTRI, Senior Research Fellow (C) Mr. MUTO Masai, Japan Transport and Tourism Research Institute, 2020 2 Contents Introduction: Objectives and Directions of the Seminar Chapter 1: Challenges in Urban Railway Development Chapter 2: Considerations for Railway Development 2.1 Collaboration Between Railways and Area Development 2.2 Securing Financial Resources : Development-Based Value Capture 2.3 Providing a High-Quality Railway System 2.4 Integration of Railway Development with Social Infrastructure 2.5 Creating a sustainable urban railway system Chapter 3: Toward Responding to Urban Transport Issues JTTRI Future Prospect (C) Mr. MUTO Masai, Japan Transport and Tourism Research Institute, 2020 3 Introduction (1) Objectives • In order to solve problems such as serious traffic congestion caused by rapid population growth ASEAN cities, integration of railway and area development will be proposed based on the local conditions in each cities. This presentation is one of the research outcomes from: “Research Group on Railway and Area Development" sponsored by JTTRI • Dr.