Formatted Dissertation with Biblio & Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Bob” Hoover IAC’S 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee

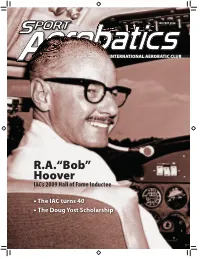

JANUARY 2010 OFFICIALOFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF TTHEHE INTERNATIONALI AEROBATIC CLUB R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee • The IAC turns 40 • The Doug Yost Scholarship PLATINUM SPONSORS Northwest Insurance Group/Berkley Aviation Sherman Chamber of Commerce GOLD SPONSORS Aviat Aircraft Inc. The IAC wishes to thank Denison Chamber of Commerce MT Propeller GmbH the individual and MX Aircraft corporate sponsors Southeast Aero Services/Extra Aircraft of the SILVER SPONSORS David and Martha Martin 2009 National Aerobatic Jim Kimball Enterprises Norm DeWitt Championships. Rhodes Real Estate Vaughn Electric BRONZE SPONSORS ASL Camguard Bill Marcellus Digital Solutions IAC Chapter 3 IAC Chapter 19 IAC Chapter 52 Lake Texoma Jet Center Lee Olmstead Andy Olmstead Joe Rushing Mike Plyler Texoma Living! Magazine Laurie Zaleski JANUARY 2010 • VOLUME 39 • NUMBER 1 • IAC SPORT AEROBATICS CONTENTS FEATURES 6 R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee – Reggie Paulk 14 Training Notes Doug Yost Scholarship – Lise Lemeland 18 40 Years Ago . The IAC comes to life – Phil Norton COLUMNS 6 3 President’s Page – Doug Bartlett 28 Just for Starters – Greg Koontz 32 Safety Corner – Stan Burks DEPARTMENTS 14 2 Letter from the Editor 4 Newsbriefs 30 IAC Merchandise 31 Fly Mart & Classifieds THE COVER IAC Hall of Famer R. A. “Bob” Hoover at the controls of his Shrike Commander. 18 – Photo: EAA Photo Archives LETTER from the EDITOR OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Publisher: Doug Bartlett by Reggie Paulk IAC Manager: Trish Deimer Editor: Reggie Paulk Senior Art Director: Phil Norton Interim Dir. of Publications: Mary Jones Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh Contributing Authors: Doug Bartlett Lise Lemeland Stan Burks Phil Norton Greg Koontz Reggie Paulk IAC Correspondence International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

Page Key to Index

PAGE KEY TO INDEX AIRCRAFT — B-17 "Flying Fortresses" 1 AIRCRAFT — Other 2 AWARDS — Military 2 AWARDS —Other 3 CITIES 3 ESCAPES and EVASIONS 10 GENERAL 10 INTERNEES 19 KILLED IN ACTION 19 MEMORIALS and CEMETERIES 20 MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS — 303rd BG 20 MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS — Other 21 MISSIONS — Target and Date 25 PERSONS 26 PRISONERS OF WAR 51 REUNIONS 51 WRITERS 52 1 El Screamo (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Miss Lace (Feb. 2004, pg. 18), (May 2004, Fast Worker II (May 2005, pg. 12) pg. 15) + (May 2005, pg. 12), (Nov. 2005, I N D E X FDR (May 2004, pg. 17) pg. 8) + (Nov. 2006, pg. 13) + (May 2007, FDR's Potato Peeler Kids (Feb. 2002, pg. pg. 16-photo) 15) + (May 2004, pg. 17) Miss Liberty (Aug. 2006, pg. 17) Flak Wolf (Aug. 2005, pg. 5), (Nov. 2005, Miss Umbriago (Aug 2003, pg. 15) AIRCRAFT pg. 18) Mugger, The (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flak Wolf II (May 2004, pg. 7) My Darling (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) B-17 "Flying Fortress" Floose (May 2004, pg. 4, 6-photo) Myasis Dragon (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flying Bison (Nov. 2006, pg. 19-photo) Nero (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flying Bitch (Aug. 2002, pg. 17) + (Feb. Neva, The Silver Lady (May 2005, pg. 15), “451" (Feb. 2002, pg. 17) 2004, pg. 18) (Aug. 2005, pg. 19) “546" (Feb. 2002, pg. 17) Fox for the F (Nov. 2004, pg. 7) Nine-O-Nine (May 2005, pg. 20) + (May 41-24577 (May 2002, pg. 12) Full House (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) 2007, pg. 20-photo) 41-24603 (Aug. -

September 2007 Newsletter

STRAIGHT SCOOP Volume XIII Number 9 September 2007 PACIFIC COAST AIR MUSEUM To promote the acquisition, restoration, safe operation, and display of historical aircraft and provide an educational venue for the community 20 August 2007 Dear Dave, Each Year I think that year’s Air Show couldn’t be beat. This year you proved me wrong again! The Pacific Coast Air Museum Air Show excelled in every aspect; the performances, the timing, static displays, announcements, traffic control and parking, the Pilot’s Tent and so many others. I can only imagine how hard you and your folks work in planning for and implementing this very significant contribution to avia- tion and Sonoma County. I am very impressed with the spirit of every one of the PCAM members and the host of volunteers. A big thanks to you and those who helped plan and carry out this memorable event. Sincerely, Jim Eade, General, United States Air Force (Retired) Air Show Survivor’s BBQ We had one terrific Air Show. By every measure, it was the best ever. Now, for those members who helped put on our Air Show, the Survivor’s BBQ is a chance to relax, pat ourselves on the back, tell “war stories”, and have a good time without all the stress of Air Show prep, or Air Show day, or Air Show take down, or Air Show put away. DATE: Saturday, September 22nd PLACE: East Patio, Pacific Coast Air Museum TIME: 3:00 PM until ??? (we have lights now!!). We will supply the meat, bread, salad, wine, beer, and soft drinks and water. -

Inspiring Women Pilots Since 1929

Ninety-Nines Inspiring Women Pilots Since 1929 September/October 2020 A High Flying Family Ninety-Nines magazine – SEPTEMBER • OCTOBER – 2020 1 Ninety-Nines Inspiring Women Pilots Since 1929 Copyright 2020, All Rights Reserved Contents Florence ‘Shutsy’ Reynolds was born Ask a DPE — by Julie Paasch p.7 with the heart of a pilot. She became the first woman to earn a Amandine Hivert: Following the Contrails pilot cetificate at her of her Father and Grandfather p.10 local airport and later — by Linda Mae Hivert qualified for the Civil Air Patrol. Shutsy's Florence Shutsy Reynolds next dream was to A WASP Forever p.12 train as a WASP. — by Roberta Roe She was admitted to the program and graduated in 1944. PAGE 12 The Ninety-Nines magazine welcomes Southwest Section new columnist, Julie Vice Governor Dea Paasch, a pilot for Payette was crowned 21 years and now Mrs. California on a DPE. She’s ready August 15, 2020. She to answer your will then compete questions, and, as for the National title she says, there are of Mrs. America in no “dumb ones.” Las Vegas, Nevada. It is a preliminary competition to the PAGE 7 Mrs. World pageant. PAGE 8 On The Cover French Section member Amandine Hivert is a third generation pilot, following her father and grandfather into the skies. She is now married to an aerobatic pilot, and she also competed in intermediate aerobatics. Amandine flew for a boutique airline serving Newark and Nice. She still trains on the Airbus and practices aerobatics. See story page 10. -

A Publication of the Southern Museum of Flight Birmingham, Al

A PUBLICATION OF THE SOUTHERN MUSEUM OF FLIGHT BIRMINGHAM, AL WWW.SOUTHERNMUSEUMOFFLIGHT.ORG FLIGHTLINES Message From The Director Board Officers n the spirit of Thanksgiving and this I Holiday Season, let me take this George Anderson Holly Roe opportunity to thank all of our museum family Steve Glenn Susan Shaw Paul Maupin Jim Thompson members for the tireless dedication and Finance Director, City of Birmingham support through this challenging year. Our museum staff, volunteers, board members, visitors, and patrons are the reason we continue to serve as one of the finest Board Members educational resources in the community, as well as one of the Matt Mielke premier aviation museums in the country. Like I’ve mentioned Al Allenback Ruby Archie Jay Miller before, throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic and all of the Dr. Brian Barsanti Jamie Moncus response efforts, our museum family has not wavered in support J. Ronald Boyd Michael Morgan and dedication for our education-oriented mission, and I could Mary Alice Carmichael Alan Moseley Chuck Conour Dr. George Petznick not be more proud to have the opportunity to serve alongside Marlin Priest such great individuals. Ken Coupland Whitney Debardelaben Raymon Ross Dr. Jim Griffin (Emeritus) Herb Rossmeisl Since our last Quarterly Edition of Flight Lines, we’ve hit several Richard Grimes Dr. Logan Smith milestones at the Southern Museum of Flight, including our Lee Hurley Clint Speegle Robert Jaques Dr. Ed Stevenson Grand Reopening following the COVID-19 shutdown earlier this Ken Key Billy Strickland year. For our visitors, things look a little different around the Rick Kilgore Thomas Talbot museum with polycarbonate shields, hand sanitizing stations, Austin Landry J. -

Finding Aid to the Purdue Air Race Classic Team Papers, 1994-2005

FINDING AID TO THE PURDUE AIR RACE CLASSIC TEAM PAPERS, 1994-2005 Purdue University Libraries Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center 504 West State Street West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2058 (765) 494-2839 http://www.lib.purdue.edu/spcol © 2013 Purdue University Libraries. All rights reserved. Revised by: Amanda Burdick, December 8, 2016 Processed by: Mary A. Sego, January 7, 2013 Descriptive Summary Creator Information Eiff, Mary Ann, 1944- Title Purdue Air Race Classic Team papers Collection Identifier UA 54 Date Span 1994-2005, predominant 1994-1998 Abstract The papers feature Purdue Air Race Classic team photographs, clippings, correspondence, general race information; including participant lists and race results, Purdue team updates provided throughout the races and Air Race Classic programs which document Purdue’s involvement in the races from 1994 – 2005. The papers also contain numerous clippings about the tragic plane crash that occurred at the Purdue Airport in September 1997, which killed Purdue Air Race Classic team member, Julie Swengel, fellow student, Anthony Kinkade and their instructor, Jeremy Sanborn. Included are Sanborn’s and Swengel’s memorial booklets. The materials were provided by Mary Ann Eiff, Purdue assistant professor of Aviation Technology and faculty adviser for Purdue Women in Aviation. Extent 1 cubic feet (2 mss boxes) Finding Aid Author Mary A. Sego, 2013 Languages English Repository Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University -

Bendix Air Races Collection

Bendix Air Races Collection Melissa A. N. Keiser 2020 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Bendix Trophy Races, General Information.............................................. 5 Series 2: Bendix Trophy Races by Year, 1931-1947............................................... 6 Series 3: Bendix Trophy Race Commemorations, 1985........................................ 15 Series 4: Bendix Public Relations and Advertising, Special Projects..................... 16 Series 5: Bendix Corporation, Miscellaneous....................................................... -

FOKKER and the USAAS T-3 COMPETITION by Gert P.M

FOKKER and the USAAS T-3 COMPETITION By Gert P.M. Blüm The still unpainted F.V Monoplane shortly after its completion at Schiphol Airport, without registration. This photo dates from early 1923. (Netherland Fokker photo 466 from the Gert Blüm collection) n April 1923 in the U.S. aviation press, there appeared Foothold in the U.S. several articles on the Dutch Fokker F.V airliner. It was In the early 1920s, Anthony Fokker put a lot of energy Idescribed as a logical successor in the line of earlier Fokker and cost into selling his hardware in the U.S. A branch of his transport aircraft. Of these, the F.IV, or Air Service T-2, was Dutch company had an offi ce at 286 Fifth Ave. in New York already well known in the U.S. for its world endurance record with Robert B.C. Noorduyn in charge. With WWI still fresh and long distance fl ights. Its nonstop transcontinental fl ight had in people’s minds, the branch was named Netherlands Aircraft yet to come. Manufacturing Co. (NAMC), omitting the Fokker name, which As Anthony H.G. “Tony” Fokker stated after his four- was also dropped from the Dutch fi rm’s title at the time: N.V. minute fi rst fl ight in the F.V that it fl ew like a mob, the positive Nederlandsche Vliegtuigenfabriek (NVNV). Originally the introduction in the contemporary press was at least remarkable. Fokker name was printed only on the branch’s letterhead, When the War Department instructed the Air Service on June 24, although later on the well known logo was added. -

2007 Chapter Officers

OUR ROOTS: AEROBATICS IN THE ‘60’s With the onset of cold weather and the lack of chapter news, I will take liberties with this installment to share some of our heritage. I first participated in formal aerobatic competition in 1968. At that time US competition was sanctioned by the ACA (Aerobatic Club of America) and was divided into three competition categories: Primary, Advanced and Unlimited. After three wins, Primary contestants were required to move up. In 1968 I was married with two boys and earning a whopping $820 a month as a chemistry instructor. I competed that year in Primary with a stock 65 hp J3 Cub. The ’68 Primary sequence was well designed and accommodated good energy management: Spin Loop Immelman 45 down snap Half Cuban Barrel Roll Hammerhead Slow Roll Reverse Half Cuban Four Point Roll Those of us without inverted fuel often experienced loss of power during the Immelman and appreciated the subsequent 45 down line in order to restart our engines. Contests in ’68 were held at Monroe, LA; Vandalia, IL; Ottumwa, IA; Rockford (Harvard) IL and the Nationals at Oak Grove airport, Fort Worth, TX. One of the pleasures of this era was the wide variety of competing aircraft. They included a lively mix of both monoplanes (clipped Cub and T-Craft, Luscombe, Ryan PT-22 and STA, Citabria, Stitts Playboy, Cassutt Racer, Chipmunk, Dart, and Zlin) and biplanes (Smith Miniplane, EAA Biplane, Pitts Special, PJ-260, Stampe, Bucker Jungmeister and Jungmann, Great Lakes, Wacos, and Stearman). Many of these early airplanes were modified to enhance their strength, control systems and to implement inverted power. -

Monday December 18, 1995

12±18±95 Monday Vol. 60 No. 242 December 18, 1995 Pages 65017±65234 Briefings on How To Use the Federal Register For information on briefings in Washington, DC, see announcement on the inside cover of this issue. federal register 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 242 / Monday, December 18, 1995 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES PUBLIC Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), by General online information 202±512±1530 the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Single copies/back copies: Act (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the Paper or fiche 512±1800 regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register Assistance with public single copies 512±1803 (1 CFR Ch. I). Distribution is made only by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC FEDERAL AGENCIES 20402. Subscriptions: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 523±5243 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 523±5243 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and For other telephone numbers, see the Reader Aids section Executive Orders and Federal agency documents having general applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published at the end of this issue. by act of Congress and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless THE FEDERAL REGISTER earlier filing is requested by the issuing agency. -

APH Fall 2018 Issue Final

FALL 2018 - Volume 65, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

Memphis Belle” Exhibit Tech

NORTHERN SENTRY FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 1 FREE | WWW.NORTHERNSENTRY.COM | VOL. 56 • ISSUE 39 | MINOT AIR FORCE BASE | FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 Team Minot hosts Military Retiree Appreciation day at MAFB U.S. AIR FORCE PHOTO | SENIOR AIRMAN LEILANI BOSTER 2 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 NORTHERN SENTRY Air Force hosts EFMP summit for exceptional family members RICHARD SALOMON | AIR FORCE’S PERSONNEL CENTER JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-RANDOLPH, Texas (AFNS) -- eing the parent of a child with asthma, cancer, autism or any Bother life-threatening or chronic condition is often a diffi cult journey that requires patience and sacrifi ce. Fortunately, thousands of active-duty members have found support through the Air Force Exceptional Family Member Program, which allows Airmen to proceed to assignment locations where suitable medical, educational and other resources are available to treat family members with special needs. In an eff ort to communicate directly with Airmen and families, the Air Force hosted an EFMP summit at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph, Texas, Aug. 28-29 to address concerns, help identify solutions and share resources for exceptional family members from each major command. The summit was also broadcast live on the EFMP- Assignments Facebook page. An Exceptional Family Member is a family member The Air Force hosted an Exceptional Family Member Program summit Aug. 28-29 at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph, Texas. EFMP allows Airmen to pro- enrolled in the Defense ceed to assignment locations where suitable medical, educational and other resources are available to treat special needs family members. Enrollment Eligibility Reporting U.S.