Chapter 7 Many-Electron Atoms (We Only Have 2 Days for Chapter 7!)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 16, 2014

October 16, 2014 Chapter 5: Electrons in Atoms Honors Chemistry Bohr Model Niels Bohr, a young Danish physicist and a student of Rutherford improved Rutherford's model. Bohr proposed that an electron is found only in specific circular paths, or orbits, around the nucleus. Each electron orbit has a fixed energy. Energy levels: the fixed energies of an electron. Quantum: The amount of energy required to move an electron from one energy level to another level. Light Electrons can jump from one energy level to another. The term quantum leap can be used to describe an The modern quantum model grew out of the study of light. 1. Light as a wave abrupt change in energy. 2. Light as a particle -Newton was the first to try to explain the behavior of light by assuming that light consists of particles. October 16, 2014 Light as a Wave 1. Wavelength-shortest distance between equivalent points on a continuous wave. symbol: λ (Greek letter lambda) 2. Frequency- the number of waves that pass a point per second. symbol: ν (Greek letter nu) 3. Amplitude-wave's height from the origin to the crest or trough. 4. Speed-all EM waves travel at the speed of light. symbol: c=3.00 x 108 m/s in a vacuum The speed of light Calculate the following: 8 1. The wavelength of radiation with a frequency of 1.50 x 1013 c=3.00 x 10 m/s Hz. Does this radiation have a longer or shorter wavelength than red light? (2.00 x 10-5 m; longer than red) c=λν 2. -

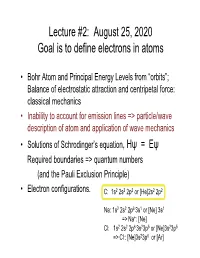

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal Is to Define Electrons in Atoms

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal is to define electrons in atoms • Bohr Atom and Principal Energy Levels from “orbits”; Balance of electrostatic attraction and centripetal force: classical mechanics • Inability to account for emission lines => particle/wave description of atom and application of wave mechanics • Solutions of Schrodinger’s equation, Hψ = Eψ Required boundaries => quantum numbers (and the Pauli Exclusion Principle) • Electron configurations. C: 1s2 2s2 2p2 or [He]2s2 2p2 Na: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1 or [Ne] 3s1 => Na+: [Ne] Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s23p5 or [Ne]3s23p5 => Cl-: [Ne]3s23p6 or [Ar] What you already know: Quantum Numbers: n, l, ml , ms n is the principal quantum number, indicates the size of the orbital, has all positive integer values of 1 to ∞(infinity) (Bohr’s discrete orbits) l (angular momentum) orbital 0s l is the angular momentum quantum number, 1p represents the shape of the orbital, has integer values of (n – 1) to 0 2d 3f ml is the magnetic quantum number, represents the spatial direction of the orbital, can have integer values of -l to 0 to l Other terms: electron configuration, noble gas configuration, valence shell ms is the spin quantum number, has little physical meaning, can have values of either +1/2 or -1/2 Pauli Exclusion principle: no two electrons can have all four of the same quantum numbers in the same atom (Every electron has a unique set.) Hund’s Rule: when electrons are placed in a set of degenerate orbitals, the ground state has as many electrons as possible in different orbitals, and with parallel spin. -

Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values

268 A Textbook of Physical Chemistry – Volume I Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values The Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen and hydrogen-like species in the polar coordinates can be written as: 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕2휓 8휋2휇 푍푒2 (406) [ (푟2 ) + (푆푖푛휃 ) + ] + (퐸 + ) 휓 = 0 푟2 휕푟 휕푟 푆푖푛휃 휕휃 휕휃 푆푖푛2휃 휕휙2 ℎ2 푟 After separating the variables present in the equation given above, the solution of the differential equation was found to be 휓푛,푙,푚(푟, 휃, 휙) = 푅푛,푙. 훩푙,푚. 훷푚 (407) 2푍푟 푘 (408) 3 푙 푘=푛−푙−1 (−1)푘+1[(푛 + 푙)!]2 ( ) 2푍 (푛 − 푙 − 1)! 푍푟 2푍푟 푛푎 √ 0 = ( ) [ 3] . exp (− ) . ( ) . ∑ 푛푎0 2푛{(푛 + 푙)!} 푛푎0 푛푎0 (푛 − 푙 − 1 − 푘)! (2푙 + 1 + 푘)! 푘! 푘=0 (2푙 + 1)(푙 − 푚)! 1 × √ . 푃푚(퐶표푠 휃) × √ 푒푖푚휙 2(푙 + 푚)! 푙 2휋 It is obvious that the solution of equation (406) contains three discrete (n, l, m) and three continuous (r, θ, ϕ) variables. In order to be a well-behaved function, there are some conditions over the values of discrete variables that must be followed i.e. boundary conditions. Therefore, we can conclude that principal (n), azimuthal (l) and magnetic (m) quantum numbers are obtained as a solution of the Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen atom; and these quantum numbers are used to define various quantum mechanical states. In this section, we will discuss the properties and significance of all these three quantum numbers one by one. Principal Quantum Number The principal quantum number is denoted by the symbol n; and can have value 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…..∞. -

Performance of Numerical Approximation on the Calculation of Two-Center Two-Electron Integrals Over Non-Integer Slater-Type Orbitals Using Elliptical Coordinates

Performance of numerical approximation on the calculation of two-center two-electron integrals over non-integer Slater-type orbitals using elliptical coordinates A. Bağcı* and P. E. Hoggan Institute Pascal, UMR 6602 CNRS, University Blaise Pascal, 24 avenue des Landais BP 80026, 63177 Aubiere Cedex, France [email protected] Abstract The two-center two-electron Coulomb and hybrid integrals arising in relativistic and non- relativistic ab-initio calculations of molecules are evaluated over the non-integer Slater-type orbitals via ellipsoidal coordinates. These integrals are expressed through new molecular auxiliary functions and calculated with numerical Global-adaptive method according to parameters of non-integer Slater- type orbitals. The convergence properties of new molecular auxiliary functions are investigated and the results obtained are compared with results found in the literature. The comparison for two-center two- electron integrals is made with results obtained from one-center expansions by translation of wave- function to same center with integer principal quantum number and results obtained from the Cuba numerical integration algorithm, respectively. The procedures discussed in this work are capable of yielding highly accurate two-center two-electron integrals for all ranges of orbital parameters. Keywords: Non-integer principal quantum numbers; Two-center two-electron integrals; Auxiliary functions; Global-adaptive method *Correspondence should be addressed to A. Bağcı; e-mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction The idea of considering the principal quantum numbers over Slater-type orbitals (STOs) in the set of positive real numbers firstly introduced by Parr [1] and performed for the He atom and single- center calculations on the H2 molecule to demonstrate that improved accuracy can be achieved in Hartree-Fock-Roothaan (HFR) calculations. -

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom Quantum Numbers In order to describe the probable location of electrons, they are assigned four numbers called quantum numbers. The quantum numbers of an electron are kind of like the electron’s “address”. No two electrons can be described by the exact same four quantum numbers. This is called The Pauli Exclusion Principle. • Principle quantum number: The principle quantum number describes which orbit the electron is in and therefore how much energy the electron has. - it is symbolized by the letter n. - positive whole numbers are assigned (not including 0): n=1, n=2, n=3 , etc - the higher the number, the further the orbit from the nucleus - the higher the number, the more energy the electron has (this is sort of like Bohr’s energy levels) - the orbits (energy levels) are also called shells • Angular momentum (azimuthal) quantum number: The azimuthal quantum number describes the sublevels (subshells) that occur in each of the levels (shells) described above. - it is symbolized by the letter l - positive whole number values including 0 are assigned: l = 0, l = 1, l = 2, etc. - each number represents the shape of a subshell: l = 0, represents an s subshell l = 1, represents a p subshell l = 2, represents a d subshell l = 3, represents an f subshell - the higher the number, the more complex the shape of the subshell. The picture below shows the shape of the s and p subshells: (notice the electron clouds) • Magnetic quantum number: All of the subshells described above (except s) have more than one orientation. -

1 Introduction 2 Spins As Quantized Magnetic Moments

Spin 1 Introduction For the past few weeks you have been learning about the mathematical and algorithmic background of quantum computation. Over the course of the next couple of lectures, we'll discuss the physics of making measurements and performing qubit operations in an actual system. In particular we consider nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Before we get there, though, we'll discuss a very famous experiment by Stern and Gerlach. 2 Spins as quantized magnetic moments The quantum two level system is, in many ways, the simplest quantum system that displays interesting behavior (this is a very subjective statement!). Before diving into the physics of two-level systems, a little on the history of the canonical example: electron spin. In 1921, Stern proposed an experiment to distinguish between Larmor's classical theory of the atom and Sommerfeld's quantum theory. Each theory predicted that the atom should have a magnetic moment (i.e., it should act like a small bar magnet). However, Larmor predicted that this magnetic moment could be oriented along any direction in space, while Sommerfeld (with help from Bohr) predicted that the orientation could only be in one of two directions (in this case, aligned or anti-aligned with a magnetic field). Stern's idea was to use the fact that magnetic moments experience a linear force when placed in a magnetic field gradient. To see this, not that the potential energy of a magnetic dipole in a magnetic field is given by: U = −~µ · B~ Here, ~µ is the vector indicating the magnitude and direction of the magnetic moment. -

Spin the Evidence of Intrinsic Angular Momentum Or Spin and Its

Spin The evidence of intrinsic angular momentum or spin and its associated magnetic moment came through experiments by Stern and Gerlach and works of Goudsmit and Uhlenbeck. The spin is called intrinsic since, unlike orbital angular momentum which is extrinsic, it is carried by point particle in addition to its orbital angular momentum and has nothing to do with motion in space. The magnetic moment ~µ of silver atom was measured in 1922 experiment by Stern and Gerlach and its projection µz in the direction of magnetic fieldz ^ B (through which the silver beam was passed) was found to be just −|~µj and +j~µj instead of continuously varying between these two as limits. Classically, magnetic moment is proportional to the angular momentum (12) and, assuming this proportionality to survive in quantum mechanics, quan- tization of magnetic moment leads to quantization of corresponding angular momentum S, which we called spin, q q µ = g S ) µ = g ~ m (57) z 2m z z 2m s as is the case with orbital angular momentum, where the ratio q=2m is called Bohr mag- neton, µb and g is known as Lande-g factor or gyromagnetic factor. The g-factor is 1 for orbital angular momentum and hence corresponding magnetic moment is l µb (where l is integer orbital angular momentum quantum number). A surprising feature here is that spin magnetic moment is also µb instead of µb=2 as one would naively expect. So it turns out g = 2 for spin { an effect that can only be understood if linearization of Schr¨odinger equation is attempted i.e. -

7. Examples of Magnetic Energy Diagrams. P.1. April 16, 2002 7

7. Examples of Magnetic Energy Diagrams. There are several very important cases of electron spin magnetic energy diagrams to examine in detail, because they appear repeatedly in many photochemical systems. The fundamental magnetic energy diagrams are those for a single electron spin at zero and high field and two correlated electron spins at zero and high field. The word correlated will be defined more precisely later, but for now we use it in the sense that the electron spins are correlated by electron exchange interactions and are thereby required to maintain a strict phase relationship. Under these circumstances, the terms singlet and triplet are meaningful in discussing magnetic resonance and chemical reactivity. From these fundamental cases the magnetic energy diagram for coupling of a single electron spin with a nuclear spin (we shall consider only couplings with nuclei with spin 1/2) at zero and high field and the coupling of two correlated electron spins with a nuclear spin are readily derived and extended to the more complicated (and more realistic) cases of couplings of electron spins to more than one nucleus or to magnetic moments generated from other sources (spin orbit coupling, spin lattice coupling, spin photon coupling, etc.). Magentic Energy Diagram for A Single Electron Spin and Two Coupled Electron Spins. Zero Field. Figure 14 displays the magnetic energy level diagram for the two fundamental cases of : (1) a single electron spin, a doublet or D state and (2) two correlated electron spins, which may be a triplet, T, or singlet, S state. In zero field (ignoring the electron exchange interaction and only considering the magnetic interactions) all of the magnetic energy levels are degenerate because there is no preferred orientation of the angular momentum and therefore no preferred orientation of the magnetic moment due to spin. -

Quantum Spin Systems and Their Local and Long-Time Properties Carolee Wheeler Faculty Advisor: Robert Sims

URA Project Proposal Quantum Spin Systems and Their Local and Long-Time Properties Carolee Wheeler Faculty Advisor: Robert Sims In quantum mechanics, spin is an important concept having to do with atomic nuclei, hadrons, and elementary particles. Spin may be thought of as a measure of a particle’s rotation about its axis. However, spin differs from orbital angular momentum in the sense that the particles may carry integer or half-integer quantum numbers, i.e. 0, 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, etc., whereas orbital angular momentum may only take integer quantum numbers. Furthermore, the spin of a charged elementary particle is related to a magnetic dipole moment. All quantum mechanic particles have an inherent spin. This is due to the fact that elementary particles (such as photons, electrons, or quarks) cannot be divided into smaller entities. In other words, they cannot be viewed as particles that are made up of individual, smaller particles that rotate around a common center. Thus, the spin that elementary particles carry is an intrinsic property [1]. An important characteristic of spin in quantum mechanics is that it is quantized. The magnitude of spin takes values S = h s(s + )1 , with h being the reduced Planck’s constant and s being the spin quantum number (a non- negative integer or half-integer). Spin may also be viewed in composite particles, and is calculated by summing the spins of the constituent particles. In the case of atoms and molecules, spin is the sum of the spins of unpaired electrons [1]. Particles with spin can possess a magnetic moment. -

The Principal Quantum Number the Azimuthal Quantum Number The

To completely describe an electron in an atom, four quantum numbers are needed: energy (n), angular momentum (ℓ), magnetic moment (mℓ), and spin (ms). The Principal Quantum Number This quantum number describes the electron shell or energy level of an atom. The value of n ranges from 1 to the shell containing the outermost electron of that atom. For example, in caesium (Cs), the outermost valence electron is in the shell with energy level 6, so an electron incaesium can have an n value from 1 to 6. For particles in a time-independent potential, as per the Schrödinger equation, it also labels the nth eigen value of Hamiltonian (H). This number has a dependence only on the distance between the electron and the nucleus (i.e. the radial coordinate r). The average distance increases with n, thus quantum states with different principal quantum numbers are said to belong to different shells. The Azimuthal Quantum Number The angular or orbital quantum number, describes the sub-shell and gives the magnitude of the orbital angular momentum through the relation. ℓ = 0 is called an s orbital, ℓ = 1 a p orbital, ℓ = 2 a d orbital, and ℓ = 3 an f orbital. The value of ℓ ranges from 0 to n − 1 because the first p orbital (ℓ = 1) appears in the second electron shell (n = 2), the first d orbital (ℓ = 2) appears in the third shell (n = 3), and so on. This quantum number specifies the shape of an atomic orbital and strongly influences chemical bonds and bond angles. -

Magnetism of Atoms and Ions

Magnetism of Atoms and Ions Wulf Wulfhekel Physikalisches Institut, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) Wolfgang Gaede Str. 1, D-76131 Karlsruhe 1 0. Overview Literature J.M.D. Coey, Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Cambridge University Press, 628 pages (2010). Very detailed Stephen J. Blundell, Magnetism in Condensed Matter, Oxford University Press, 256 pages (2001). Easy to read, gives a condensed overview C. Kittel, Introduction to Solid State Physics, John Whiley and Sons (2005). Solid state aspects 2 0. Overview Chapters of the two lectures 1. A quick refresh of quantum mechanics 2. The Hydrogen problem, orbital and spin angular momentum 3. Multi electron systems 4. Paramagnetism 5. Dynamics of magnetic moments and EPR 6. Crystal fields and zero field splitting 7. Magnetization curves with crystal fields 3 1. A quick refresh of quantum mechanics The equation of motion The Hamilton function: with T the kinetic energy and V the potential, q the positions and p the momenta gives the equations of motion: Hamiltonian gives second order differential equation of motion and thus p(t) and q(t) Initial conditions needed for Classical equations need information on the past! t p q 4 1. A quick refresh of quantum mechanics The Schrödinger equation Quantum mechanics replacement rules for Hamiltonian: Equation of motion transforms into Schrödinger equation: Schrödinger equation operates on wave function (complex field in space) and is of first order in time. Absolute square of the wave function is the probability density to find the particle at selected position and time. t Initial conditions needed for Schrödinger equation does not need information on the past! How is that possible? We know that the past influences the present! q 5 1. -

Chem 1A Chapter 7 Exercises

Chem 1A Chapter 7 Exercises Exercises #1 Characteristics of Waves 1. Consider a wave with a wavelength = 2.5 cm traveling at a speed of 15 m/s. (a) How long does it take for the wave to travel a distance of one wavelength? (b) How many wavelengths (or cycles) are completed in 1 second? (The number of waves or cycles completed per second is referred to as the wave frequency.) (c) If = 3.0 cm but the speed remains the same, how many wavelengths (or cycles) are completed in 1 second? (d) If = 1.5 cm and the speed remains the same, how many wavelengths (or cycles) are completed in 1 second? (e) What can you conclude regarding the relationship between wavelength and number of cycles traveled in one second, which is also known as frequency ()? Answer: (a) 1.7 x 10–3 s; (b) 600/s; (c) 500/s; (d) 1000/s; (e) ?) 2. Consider a red light with = 750 nm and a green light = 550 nm (a) Which light travels a greater distance in 1 second, red light or green light? Explain. (b) Which light (red or green) has the greater frequency (that is, contains more waves completed in 1 second)? Explain. (c) What are the frequencies of the red and green light, respectively? (d) If light energy is defined by the quantum formula, such that Ep = h, which light carries more energy per photon? Explain. 8 -34 (e) Assuming that the speed of light, c = 2.9979 x 10 m/s, Planck’s constant, h = 6.626 x 10 J.s., and 23 Avogadro’s number, NA = 6.022 x 10 /mol, calculate the energy: (i) per photon; (ii) per mole of photon for green and red light, respectively.