Breaking the Law to Get a Break Social Site Partners with Music Label That Sued It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Industry and Digital Music

The Music Industry and Digital Music Disruptive Technology and the Value Network Effects on Industry Incumbents A thesis written by Jens Peter Larsen Cand. Merc., Master of Science, Management of Innovation & Business Development Copenhagen Business School Supervisor: Finn Valentin, Institut for innovation og organisationsøkonomi Word Count: 170.245 digits – 75 standard pages The Music Industry and Digital Music – Jens Peter Larsen, Cand. Merc. MIB Thesis Table of Content 1. Resume .................................................................................. 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................ 5 3. Research Design ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Research Question .......................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Elaboration on Research Design ................................................................................... 6 3.2.1 Technological Development ..................................................................................... 6 3.2.2 Definitions................................................................................................................. 7 4. Methodology ............................................................................ 8 4.1 Project Outlook .............................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Delimitation .................................................................................................................. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

What Is Peer-To-Peer File Transfer? Bandwidth It Can Use

sharing, with no cap on the amount of commonly used to trade copyrighted music What is Peer-to-Peer file transfer? bandwidth it can use. Thus, a single NSF PC and software. connected to NSF’s LAN with a standard The Recording Industry Association of A peer-to-peer, or “P2P,” file transfer 100Mbps network card could, with KaZaA’s America tracks users of this software and has service allows the user to share computer files default settings, conceivably saturate NSF’s begun initiating lawsuits against individuals through the Internet. Examples of P2P T3 (45Mbps) internet connection. who use P2P systems to steal copyrighted services include KaZaA, Grokster, Gnutella, The KaZaA software assesses the quality of material or to provide copyrighted software to Morpheus, and BearShare. the PC’s internet connection and designates others to download freely. These services are set up to allow users to computers with high-speed connections as search for and download files to their “Supernodes,” meaning that they provide a How does use of these services computers, and to enable users to make files hub between various users, a source of available for others to download from their information about files available on other create security issues at NSF? computers. users’ PCs. This uses much more of the When configuring these services, it is computer’s resources, including bandwidth possible to designate as “shared” not only the and processing capability. How do these services function? one folder KaZaA sets up by default, but also The free version of KaZaA is supported by the entire contents of the user’s computer as Peer to peer file transfer services are highly advertising, which appears on the user well as any NSF network drives to which the decentralized, creating a network of linked interface of the program and also causes pop- user has access, to be searchable and users. -

What's the Download® Music Survival Guide

WHAT’S THE DOWNLOAD® MUSIC SURVIVAL GUIDE Written by: The WTD Interactive Advisory Board Inspired by: Thousands of perspectives from two years of work Dedicated to: Anyone who loves music and wants it to survive *A special thank you to Honorary Board Members Chris Brown, Sway Calloway, Kelly Clarkson, Common, Earth Wind & Fire, Eric Garland, Shirley Halperin, JD Natasha, Mark McGrath, and Kanye West for sharing your time and your minds. Published Oct. 19, 2006 What’s The Download® Interactive Advisory Board: WHO WE ARE Based on research demonstrating the need for a serious examination of the issues facing the music industry in the wake of the rise of illegal downloading, in 2005 The Recording Academy® formed the What’s The Download Interactive Advisory Board (WTDIAB) as part of What’s The Download, a public education campaign created in 2004 that recognizes the lack of dialogue between the music industry and music fans. We are comprised of 12 young adults who were selected from hundreds of applicants by The Recording Academy through a process which consisted of an essay, video application and telephone interview. We come from all over the country, have diverse tastes in music and are joined by Honorary Board Members that include high-profile music creators and industry veterans. Since the launch of our Board at the 47th Annual GRAMMY® Awards, we have been dedicated to discussing issues and finding solutions to the current challenges in the music industry surrounding the digital delivery of music. We have spent the last two years researching these issues and gathering thousands of opinions on issues such as piracy, access to digital music, and file-sharing. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

Napster: Winning the Download Race in Europe

Resolution 3.5 July/Aug 04 25/6/04 12:10 PM Page 50 business Napster: winning the download race in Europe A lot of ones and zeros have passed under the digital bridge on the information highway since November 2002, when this column reviewed fledgling legal music download services. Apple has proved there’s money to be made with iTunes music store, street-legal is no longer a novelty, major labels are no longer in the game ... but the Napster name remains. NIGEL JOPSON N RESOLUTION V1.5 Pressplay, co-owned by UK. There’s an all-you-can-download 7-day trial for Universal and Sony, received top marks for user UK residents who register at the Napster.co.uk site. Iexperience. Subscription service Pressplay launched While Apple has gone with individual song sales, with distribution partnerships from Microsoft’s MSN Roxio has stuck to the subscription model and service, Yahoo and Roxio. Roxio provided the CD skewed pricing accordingly. ‘We do regard burning technology. In November 2002, Roxio acquired subscription as the way forward for online music,’ the name and assets of the famed Napster service (which Leanne Sharman told me, ‘why pay £9.90 for 10 was in Chapter 11 protective bankruptcy) for US$5m songs when the same sum gives you unlimited access and 100,000 warrants in Roxio shares. Two months to over half a million tracks?’ earlier, Napster’s sale to Bertelsmann had been blocked Subscription services have come in for heavy — amid concerns the deal had not been done in good criticism from many informed commentators — mostly faith — this after Thomas Middlehoff had invested a multi-computer and iPod owning techno journalists like reputed US$60m of Bertelsmann’s money in Napster. -

Heavy? You Must Be Crazy

YOUR FREE WEEKDAY AFTERNOON SOURCE FOR NEWS, SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 03 27 2008 Heavy? You must be crazy Sporting a belly at 40 seriously increases your chances of getting Alzheimer’s later. p.10 Look whom John McCain brought to Utah. p.4 Huge bills freak out Questar customers. p.4 All-you-can-eat seats for sports fan. p.14 SOMETHING TO BUZZ ABOUT Bartender, Another Hemotoxin Please Murder Suspect Not a Flight Risk A Texas rattlesnake rancher found Popplewell said his intent is not A morbidly obese Texas woman Mayra Lizbeth Rosales, who a new way to make money: Stick a to sell an alcoholic beverage but a who authorities originally thought weighs at least 800 pounds and is rattler inside a bottle of vodka and healing tonic. He said he uses the might have crushed her 2-year-old bedridden, was photographed and market the concoction as an “an- cheapest vodka he can find as a nephew to death was arraigned in fingerprinted at her La Joya home cient Asian elixir.” But Bayou Bob preservative for the snakes. The her bedroom Wednesday on a cap- before being released on a per- Popplewell has no liquor license and end result is a super sweet mixed ital murder charge, accused of strik- sonal recognizance bond, Hidalgo faces charges. drink he compared to cough syrup. ing him in the head. County Sheriff Lupe Trevino said. 27mar08 TheWeather Tonight Partly cloudy. 29° theprimer Sunset: 7:47 p.m. Friday 50° Mostly cloudy; 50 INTERNET percent chance of late rain and snow An Educational, Saturday and Fruitful, Site 45° Mostly cloudy; 40 A colorful, new interactive Web site, percent chance of rain designed to educate children ages 2 and snow. -

Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\7-1\HLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAR-16 12:46 Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms Loren Shokes* In the age of iPods, YouTube, Spotify, social media, and countless numbers of apps, anyone with a computer or smartphone readily has access to millions of hours of music. Despite the ever-increasing ease of delivering music to consumers, the recording industry has fallen victim to “the disease of free.”1 When digital music was first introduced in the late 1990s, indus- try experts and insiders postulated that it would parallel the introduction and eventual mainstream acceptance of the compact disc (CD). When CDs became publicly available in 1982,2 the music industry experienced an un- precedented boost in sales as consumers, en masse, traded in their vinyl records and cassette tapes for sleek new compact discs.3 However, the intro- duction of MP3 players and digital music files had the opposite effect and the recording industry has struggled to monetize and profit from the digital revolution.4 The birth of the file sharing website Napster5 in 1999 was the start of a sharp downhill turn for record labels and artists.6 Rather than pay * J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School, Class of 2017. 1 See David Goldman, Music’s Lost Decade: Sales Cut in Half, CNN Money (Feb. 3, 2010), available at http://money.cnn.com/2010/02/02/news/companies/napster_ music_industry/. 2 See The Digital Era, Recording History: The History of Recording Technology, available at http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/musicbiz7.php (last visited July 28, 2015). -

Summit Guide Guide Du Sommet Guía De La Cumbre Contents/Sommaire/Sumario

New Frontiers for Creators in the Marketplace 9-10 June 2009 – Ronald Reagan Center – Washington DC, USA www.copyrightsummit.com Summit Guide Guide du Sommet Guía de la Cumbre Contents/Sommaire/Sumario Page Welcome 1 Conference Programme 3 What’s happening around the Summit? 11 Additional Summit Information 12 Page Bienvenue 14 Programme des conférences 15 Autres événements autour du sommet ? 24 Informations supplémentaires du sommet 25 Página Bienvenidos 27 Programa de las Conferencias 28 ¿Lo que pasa alrededor del conferencia? 38 Información sobre el conferencia 39 Page Sponsor & Advisory Committee Profiles 41 Partner Organization Profiles 44 Media Partner Profiles 49 Speaker Biographies 53 9-10 June 2009 – Ronald Reagan Center – Washington DC, USA New Frontiers for Creators in the Marketplace Welcome Welcome to the World Copyright Summit! Two years on from our hugely successful inaugural event in Brussels it gives me great pleasure to welcome you all to the 2009 World Copyright Summit in Washington, DC. This year’s slogan for the Summit – “New Frontiers for Creators in the Marketplace” – illustrates perfectly what we aim to achieve here: remind to the world that creators’ contributions are fundamental for cultural, economic and social development but also that creators – and those who represent them – face several daunting challenges in this new digital economy. It is imperative that we bring to the forefront of political debate the creative industries’ future and where we, creators, fit into this new landscape. For this reason we have gathered, under the CISAC umbrella, all the stakeholders involved one way or another in the creation, production and dissemination of creative works. -

Piratez Are Just Disgruntled Consumers Reach Global Theaters That They Overlap the Domestic USA Blu-Ray Release

Moviegoers - or perhaps more accurately, lovers of cinema - are frustrated. Their frustrations begin with the discrepancies in film release strategies and timing. For example, audiences that saw Quentin Tarantino’s1 2 Django Unchained in the United States enjoyed its opening on Christmas day 2012; however, in Europe and other markets, viewers could not pay to see the movie until after the 17th of January 2013. Three weeks may not seem like a lot, but some movies can take months to reach an international audience. Some take so long to Piratez Are Just Disgruntled Consumers reach global theaters that they overlap the domestic USA Blu-Ray release. This delay can seem like an eternity for ultiscreen is at the top of the entertainment a desperate fan. This frustrated enthusiasm, combined industry’s agenda for delivering digital video. This with a lack of timely availability, leads to the feeling of M is discussed in the context of four main screens: being treated as a second class citizen - and may lead TVs, PCs, tablets and mobile phones. The premise being the over-anxious fan to engage in piracy. that multiscreen enables portability, usability and flexibility for consumers. But, there is a fifth screen which There has been some evolution in this practice, with is often overlooked – the cornerstone of the certain films being released simultaneously to a domestic and global audience. For example, Avatar3 was released entertainment industry - cinema. This digital video th th ecosystem is not complete without including cinema, and in theaters on the 10 and 17 of December in most it certainly should be part of the multiscreen discussion. -

The Quality of Recorded Music Since Napster: Evidence Based on The

Digitization and the Music Industry Joel Waldfogel Conference on the Economics of Information and Communication Technologies Paris, October 5-6, 2012 Copyright Protection, Technological Change, and the Quality of New Products: Evidence from Recorded Music since Napster AND And the Bands Played On: Digital Disintermediation and the Quality of New Recorded Music Intro – assuring flow of creative works • Appropriability – may beget creative works – depends on both law and technology • IP rights are monopolies granted to provide incentives for creation – Harms and benefits • Recent technological changes may have altered the balance – First, file sharing makes it harder to appropriate revenue… …and revenue has plunged RIAA Total Value of US Shipments, 1994-2009 16000 14000 12000 10000 total 8000 digital $ millions physical 6000 4000 2000 0 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Ensuing Research • Mostly a kerfuffle about whether file sharing cannibalizes sales • Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf (2006),Rob and Waldfogel (2006), Blackburn (2004), Zentner (2006), and more • Most believe that file sharing reduces sales • …and this has led to calls for strengthening IP protection My Epiphany • Revenue reduction, interesting for producers, is not the most interesting question • Instead: will flow of new products continue? • We should worry about both consumers and producers Industry view: the sky is falling • IFPI: “Music is an investment-intensive business… Very few sectors have a comparable proportion of sales -

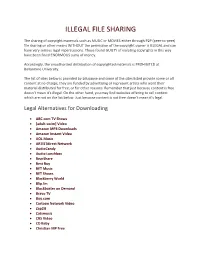

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com