Examining Health Inequity in Ancient Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodontology – the Historical Outline from Ancient Times Until the 20Th Century Istorijski Razvoj Parodontologije Zlata Brkić*†, Verica Pavli懧

Vojnosanit Pregl 2017; 74(2): 193–199. VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Page 193 UDC: 616.31(091) HISTORY OF MEDICINE DOI: 10.2298/VSP150612169B Periodontology – the historical outline from ancient times until the 20th century Istorijski razvoj parodontologije Zlata Brkić*†, Verica Pavli懧 *Clinic for Dentistry, Military Medical Academy, Belgrade, Serbia; †Faculty of Medicine of the Military Medical Academy, University of Defence, Belgrade, Serbia; ‡Department of Periodontology and Oral Medicine, Institute of Dentistry, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Department of Periodontology and Oral Medicine, §Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina Introduction cations 1–3. This finding was further confirmed by decorated gold toothpicks founded in the exavations at the Nigel Tem- The diseases of the periodontium are considered as old as ple, Ur in Mesopotamia 2. 1–3 the recorded history of mankind . The historical evaluation of Almost all of our knowledge of Babylonian and pathology and therapeutics can be traced through the variety of Assyrian medicine comes from the clay tablets of the great sources: anatomical findings from more or less well-preserved library of Ashurbanipal (king of Assyria), that includes a skeletal parts, detailes observed in mummies, instruments and number of remedies for periodontal disease, such as “if a equipments collected during archaelogical investigations and man's teeth are loose and itch a mixture of myrrh, asafetida evidence from engravings and various manuscripts 2. Studies in and opopanax, as well as pine-turpentine shall be rubbed on paleopathology have indicated that a destructive periodontal di- his teeth until blood comes forth and he shall recover” 2. -

Chest Surgical Disorders in Ancient Egypt Evidence of Advanced Knowledge

SURGICAL RETROSPECTION Chest Surgical Disorders in Ancient Egypt Evidence of Advanced Knowledge Wolfgang Jungraithmayr, MD and Walter Weder, MD canopic jars. In contrast to the heart, which was carefully retained in The ancient Egyptians laid the foundation for the development of the earliest place, the lung was removed and deposited into such a canopic jar recorded systems of medical treatment. Many specialties such as gynecology, under the protection of the God Hapy, one of the sons of Horus. neurosurgery, ophthalmology, and chest disorders were subject to diagnosis, According to Gardiner’s sign list,11 the lung and trachea to- which were followed by an appropriate treatment. Here, we elucidate the gether are provided with their own hieroglyph (Figs. 1A–C). This remarkable level of their knowledge and understanding of anatomy and phys- miniature portrait acts as a trilateral (sma), meaning “unite.” When iology in the field of chest medicine. Furthermore, we look at how ancient carefully observing the configuration of this hieroglyph, the 2 sides Egyptian physicians came to a diagnosis and treatment based on the thoracic at the lower end of the symbol resemble the right and left sides of the cases in the Edwin Smith papyrus. lung whereas the trachea might be represented by the upper part of the (Ann Surg 2012;255:605–608) sign (Fig. 1A). This theory could be supported by the observation that the hieroglyph symbol of the heart reflects the anatomy of vessels in which the blood flow leaves the organ or drains into it (Fig. 2). Thus, he autonomy of the ancient Egyptians ensured a freedom from it seems that the understanding of this physiological arrangement was T foreign intrusions that favored the development of medical ad- already recognized at that time. -

Joyful in Thebes Egyptological Studies in Honor of Betsy M

JOYFUL IN THEBES EGYPTOLOGICAL STUDIES IN HONOR OF BETSY M. BRYAN MATERIAL AND VISUAL CULTURE OF ANCIENT EGYPT Editors X xxxxx, X xxxx NUMBER ONE JOYFUL IN THEBES EGYPTOLOGICAL STUDIES IN HONOR OF BETSY M. BRYAN JOYFUL IN THEBES EGYPTOLOGICAL STUDIES IN HONOR OF BETSY M. BRYAN Edited by Richard Jasnow and Kathlyn M. Cooney With the assistance of Katherine E. Davis LOCKWOOD PRESS ATLANTA, GEORGIA JOYFUL IN THEBES EGYPTOLOGICAL STUDIES IN HONOR OF BETSY M. BRYAN Copyright © 2015 by Lockwood Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Lockwood Press, PO Box 133289, Atlanta, GA 30333 USA. Library of Congress Control Number: 2015944276 ISBN: 978-1-937040-40-6 Cover design by Deborah Shieh, adapted by Susanne Wilhelm. Cover image: Amenhotep III in the Blue Crown (detail), ca. 1390–1352 BCE. Quartzite, Ht. 35 cm. Face only: ht. 12.8 cm; w. 12.6 cm. Rogers Fund, 1956 (56.138). Image copyright © the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi Abbreviations xvii Bibliography of Betsy M. Bryan xxiv Tabula Gratulatoria xxviii T A. BÁCS Some Aspects of Tomb Reuse during the Twentieth Dynasty 1 Y BARBASH e Lion-Headed Goddess and Her Lost Cat: Brooklyn Museum 37.1379E 11 H BASSIR On the Historical Implications of Payeftjauemawyneith’s Self-Presentation on Louvre A 93 21 L M. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Practicing Medicine in Ancient Egypt

Practicing Medicine in Ancient Egypt Michael R. Zimmerman March 28, 2017 Michael Zimmerman is Adjunct Professor of Biology at Villanova University, Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, and Visiting Professor at the University of Manchester (UK) KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology. et us start by imagining what Albert Einstein called a “thought experiment.” It is the year 5015 CE L and an excavation of an ancient hospital, ca. 2016 CE, uncovers an ancient book, written on paper rather than on the current electronic device. Although the book is in poor condition there is a partial hieroglyphic title, transcribed by an Egyptologist and a paleopathologist as Merck Manual. The book seems to be a compilation of disease descriptions and treatments by a long forgotten Dr. Merck. The diseases are difficult to decipher in an era when humans live to the age of 150 and die only when aged organs fail. It appears that the body could be attacked by minute parasitic organisms, visible only with an ancient tool called a “microscope.” Some cells appear to have taken on a life of their own, destroying the body by causing diseases known by a variety of poorly preserved terms such as “cancer” or “neoplasm.” The task of our future paleopathologist is analogous to that of the difficult undertaking of deciphering ancient Egyptian medical papyri. There are a number of surviving papyri, in various degrees of completeness, which have been studied by physicians and Egyptologists. They have done remarkably well, particularly in that the writing is mostly in the difficult hieratic rather than hieroglyphic text. -

Extraction and Use of Greywacke in Ancient Egypt Ahmed Ibrahim Othman

JFTH, Vol. 14, Issue 1 (2017) ISSN: 2314-7024 Extraction and Use of Greywacke in Ancient Egypt Ahmed Ibrahim Othman 1 Lecturer – Tourism Guidance Department Hotel Management and Restoration Institute, Abu Qir. [ Introduction The Quseir – Qift road was the only practical route in the Central Easter Desert as it was the shortest and easiest road from the Nile Valley to the Red Sea, in addition to the richness of the Bekhen stone quarries and the gold mines. Therefore, it was the preferred road by the merchants, quarrymen and miners. The Bekhen stone quarries of Wadi Hammamat forms an archaeological cluster of inscriptions, unfinished manufactures, settlements, workshops and remaining tools. It seems clear that the state was responsible for the Bekhen stone exploitation, given the vast amount of resources that had to be invested in the organization of a quarrying expedition. Unlike the other marginal areas, the officials leading the missions to Wadi Hammamat show different affiliations in terms of administrative branches. This is probably because Bekhen stone procurement was not the responsibility of the treasury, but these expeditions were entrusted to separate competent officials, graded in a specific hierarchy, forming well – organized missions with different workers for different duties and established wages and functionaries in charge of the administrative tasks. The greywacke quarries were not constantly or intensively exploited. The fact that the stone was used in private or royal statuary and not as a building stone could have caused its demand to be less than that of other materials such as granite, limestone or sandstone. Inscriptions indicated the time lapse between expeditions suggesting that this stone was only quarried when it was needed, which was not on a regular basis. -

Daf Ditty Eruvin 103- Papyrus As Bandage

Daf Ditty Eruvin 103: Papyrus, Bandaging, Despair The Soul has Bandaged moments The Soul has Bandaged moments - When too appalled to stir - She feels some ghastly Fright come up And stop to look at her - Salute her, with long fingers - Caress her freezing hair - Sip, Goblin, from the very lips The Lover - hovered - o'er - Unworthy, that a thought so mean Accost a Theme - so - fair - The soul has moments of escape - When bursting all the doors - She dances like a Bomb, abroad, And swings opon the Hours, As do the Bee - delirious borne - Long Dungeoned from his Rose - Touch Liberty - then know no more - But Noon, and Paradise The Soul's retaken moments - When, Felon led along, With shackles on the plumed feet, And staples, in the song, The Horror welcomes her, again, These, are not brayed of Tongue - EMILY DICKINSON 1 Her bandaged prison of depression or despair is truly a hell from which no words can escape, whether a call for help, a poem, or a prayer. 2 3 Rashi . שדקמ but not outside of the בש ת on שדקמה ב י ת may wrap a reed over his wound in the הכ ן A If he ימג יסמ - the ימג and, wound the heals פר ו הא תבשב ובש ת ה י א . ;explains, as the Gemara later says . אד ו ר י י את א י ס ו ר because it’s an , שדקמ in the סא ו ר is trying to draw out blood, it is even MISHNA: With regard to a priest who was injured on his finger on Shabbat, he may temporarily wrap it with a reed so that his wound is not visible while he is serving in the Temple. -

Ancient Egyptian Healers Updates.Edited

Evidence-Based Nursing Research Vol. 1 No. 1 January 2019 Ancient Egyptian Healers Fatma A. Altaieb Faculty of Nursing, Ain Shams University, Egypt. e-mail: [email protected] doi: 10.47104/ebnrojs3.v1i1.27 Before the decipherment of the Rosetta stone in 1822, covering physical, mental, and spiritual diseases. The Ebers most information about ancient Egyptian medicine came Papyrus has references to eye diseases, gastrointestinal, from Greek historians and physicians, especially the head, and skin. This Papyrus has 110 pages and dates to historian Herodotus who visited Egypt around 440 BC. 1534 BC, the reign of Amenhotep I. It contains spells, a Other Greeks who extensively wrote about ancient section on gastric diseases, intestinal parasites, skin, anus Egyptian medicine include Hippocrates (460-370 BC); the diseases, a small treatise on the heart, and some two physician anatomists, Herophilos (335-280 BC) and prescriptions thought to have been used by gods. It Erasistratus (310-250 BC), who jointly founded the famous continues with migraine treatments, urinary tract medical school in the Egyptian city of Alexandria; and disturbances, coughs, hair conditions, burns and different Galen (AD 129-200), the pioneering surgeon, anatomist, wounds, extremities (fingers and toes), tongue, teeth, ears, and experimentalist. Homer copiously sang the praise of nose and throat, gynecological conditions, and the last Egyptian medicine in the Odyssey (around 800 BC). section on what is thought to be tumors. Still unidentified Egyptian medicine also had considerable influence on diseases; aaa, probably ancylostomiasis (hookworm - Hebrew and Roman medicine. However, after the endemic to ancient Egypt) (Davis, 2000; Kloos et al., destruction of pagan temples by Emperor Theodosius I in 2002). -

Joyful in Thebes an International Group of Scholars Have Contributed to Joyful Egypto Logical Studies in Honor of Betsy M

Joyful in Thebes An international group of scholars have contributed to Joyful Egypto in Thebes, a Festschrift for the distinguished Egyptologist Betsy M. Bryan. The forty-two articles deal with topics of art history, archaeology, history, and philology, representing virtually the entire span of ancient Egyptian civilization. logical Studies in Honor of Betsy M. Bryan These diverse studies, which often present unpublished material or new interpretations of specific issues in Egyptian history, literature, and art history, well reflect the broad research interests of the honoree. Abundantly illustrated with photographs and line drawings, the volume also includes a comprehensive bibliography of Bryan’s publications through 2015. Richard Jasnow is professor of Kathlyn M. Cooney is Egyptological Studies in Honor of Egyptology at Johns Hopkins University. associate professor of Egyptian He has authored A Late Period Hieratic Art and Architecture at UCLA. She Betsy M. Bryan Wisdom Text (P. Brooklyn 47.218.135) is author of The Cost of Death: (The Oriental Institute of the University The Social and Economic Value of of Chicago, 1992) and The Ancient Ancient Egyptian Funerary Art in Egyptian Book of Thoth (Harrassowitz, the Ramesside Period (Nederlands 2005; with Karl-Theodor Zauzich). Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 2007) Jasnow’s research focuses on Demotic and The Woman Who Would Be King: texts of the Graeco-Roman period. Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt (Crown, 2014). Her research Kathlyn M. Cooney Katherine E. Davis is a focuses on craft specialization, Richard Jasnow graduate student in Egyptology ancient economics, funerary material at Johns Hopkins University. culture, and social crisis. -

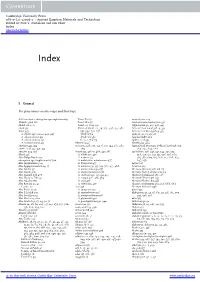

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

The Body Both Shapes and Is Shaped by an Individual’S Social Roles

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Body Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8f21r7sj Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Riggs, Christina Publication Date 2010-11-17 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California BODY الجسد Christina Riggs EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor Area Editor Individual and Society University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Riggs 2010, Body. UEE. Full Citation: Riggs, Christina, 2010, Body. In Elizabeth Frood, Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0025nqg2 1149 Version 1, November 2010 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0025nqg2 BODY الجسد Christina Riggs Körper Corps The human body is both the physical form inhabited by an individual “self” and the medium through which an individual engages with society. Hence the body both shapes and is shaped by an individual’s social roles. In contrast to the cognate fields of archaeology, anthropology, and classics, there has been little explicit discussion or theorization of the body in Egyptology. Some recent works, discussed here, constitute an exception to this trend, but there is much more scope for exploring ancient Egyptian culture through the body, especially as evidenced in works of art and pictorial representation. جسد اﻹنسان عبارة عن الجسد المادي الذي تقطنه «النفس» المتفردة، وھو الوسيلة التى يقوم من خﻻلھا اﻹنسان بالتفاعل مع المجتمع. ومن ثم فالجسد يشكل ويتكيف على حد سواء تبعا للوظائف اﻻجتماعية الفردية. -

Egyptian Gardens

Studia Antiqua Volume 6 Number 1 Article 5 June 2008 Egyptian Gardens Alison Daines Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Daines, Alison. "Egyptian Gardens." Studia Antiqua 6, no. 1 (2008). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ studiaantiqua/vol6/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Egyptian Gardens Alison Daines he gardens of ancient Egypt were an integral component of their religion Tand surroundings. The gardens cannot be excavated like buildings and tombs can be, but archeological relics remain that have helped determine their construction, function, and symbolism. Along with these excavation reports, representations of gardens and plants in painting and text are available (fig. 1).1 These portrayals were frequently located on tomb and temple walls. Assuming these representations were based on reality, the gardens must have truly been spectacular. Since the evidence of gardens on excavation sites often matches wall paintings, scholars are able to learn a lot about their purpose.2 Unfortunately, despite these resources, it is still difficult to wholly understand the arrangement and significance of the gardens. In 1947, Marie-Louise Buhl published important research on the symbol- ism of local vegetation. She drew conclusions about tree cults and the specific deity that each plant or tree represented. In 1994 Alix Wilkinson published an article on the symbolism and forma- tion of the gardens, and in 1998 published a book on the same subject.