Microemboli Are Not a Prerequisite in Retinal Artery Occlusive Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venous Air Embolism, Result- Retrospective Study of Patients with Venous Or Arterial Ing in Prompt Hemodynamic Improvement

Ⅵ REVIEW ARTICLE David C. Warltier, M.D., Ph.D., Editor Anesthesiology 2007; 106:164–77 Copyright © 2006, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vascular Air Embolism Marek A. Mirski, M.D., Ph.D.,* Abhijit Vijay Lele, M.D.,† Lunei Fitzsimmons, M.D.,† Thomas J. K. Toung, M.D.‡ exogenously delivered gas) from the operative field or This article has been selected for the Anesthesiology CME Program. After reading the article, go to http://www. other communication with the environment into the asahq.org/journal-cme to take the test and apply for Cate- venous or arterial vasculature, producing systemic ef- gory 1 credit. Complete instructions may be found in the fects. The true incidence of VAE may be never known, CME section at the back of this issue. much depending on the sensitivity of detection methods used during the procedure. In addition, many cases of Vascular air embolism is a potentially life-threatening event VAE are subclinical, resulting in no untoward outcome, that is now encountered routinely in the operating room and and thus go unreported. Historically, VAE is most often other patient care areas. The circumstances under which phy- associated with sitting position craniotomies (posterior sicians and nurses may encounter air embolism are no longer fossa). Although this surgical technique is a high-risk limited to neurosurgical procedures conducted in the “sitting procedure for air embolism, other recently described position” and occur in such diverse areas as the interventional radiology suite or laparoscopic surgical center. Advances in circumstances during both medical and surgical thera- monitoring devices coupled with an understanding of the peutics have further increased concern about this ad- pathophysiology of vascular air embolism will enable the phy- verse event. -

Pulmonary Embolism a Pulmonary Embolism Occurs When a Blood Clot Moves Through the Bloodstream and Becomes Lodged in a Blood Vessel in the Lungs

Pulmonary Embolism A pulmonary embolism occurs when a blood clot moves through the bloodstream and becomes lodged in a blood vessel in the lungs. This can make it hard for blood to pass through the lungs to get oxygen. Diagnosing a pulmonary embolism can be difficult because half of patients with a clot in the lungs have no symptoms. Others may experience shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, and possibly swelling in the legs. If you have a pulmonary embolism, you need medical treatment right away to prevent a blood clot from blocking blood flow to the lungs and heart. Your doctor can confirm the presence of a pulmonary embolism with CT angiography, or a ventilation perfusion (V/Q) lung scan. Treatment typically includes medications to thin the blood or placement of a filter to prevent the movement of additional blood clots to the lungs. Rarely, drugs are used to dissolve the clot or a catheter-based procedure is done to remove or treat the clot directly. What is a pulmonary embolism? Blood can change from a free flowing fluid to a semi-solid gel (called a blood clot or thrombus) in a process known as coagulation. Coagulation is a normal process and necessary to stop bleeding and retain blood within the body's vessels if they are cut or injured. However, in some situations blood can abnormally clot (called a thrombosis) within the vessels of the body. In a condition called deep vein thrombosis, clots form in the deep veins of the body, usually in the legs. A blood clot that breaks free and travels through a blood vessel is called an embolism. -

Pulmonary Embolism in the First Trimester of Pregnancy

Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal Case Report Open Access Pulmonary embolism in the first trimester of pregnancy Summary Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2020 Pulmonary embolism in the first trimester of pregnancy without a known medical history Orfanoudaki Irene M is a very rare complication, which if it is misdiagnosed and left untreated leads to sudden Obstetric Gynecology, University of Crete, Greece pregnancy-related death. The sings and symptoms in this trimester are no specific. The causes for pulmonary embolism are multifactorial but in the first trimester of pregnancy, Correspondence: Orfanoudaki Irene M, Obstetric the most important causes are hereditary factors. Many times the pregnant woman ignores Gynecology, University of Crete, Greece, 22 Archiepiskopou her familiar hereditary history and her hemostatic system is progressively activated for the Makariou Str, 71202, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, Tel +30 hemostatic challenge of pregnancy and delivery. The hemostatic changes produce enhance 6945268822, +302810268822, Email coagulation and formation of micro-thrombi or thrombi and prompt diagnosis is crucial to prevent and treat pulmonary embolism saving the lives of a pregnant woman and her fetus. Received: January 19, 2020 | Published: January 28, 2020 Keywords: pregnancy, pulmonary embolism, mortality, diagnosis, risk factors, arterial blood gases, electrocardiogram, ventilation perfusion scan, computed tomography pulmonary angiogram, magnetic resonanance, compression ultrasonography, echocardiogram, D-dimers, troponin, brain -

Pulmonary Embolism

JAMA PATIENT PAGE The Journal of the American Medical Association VASCULAR DISEASE Pulmonary Embolism How pulmonary embolism occurs Pulmonary 3 The embolus obstructs artery a vessel in the lung and Lung pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blood clot that deprives tissue of blood. blocks the blood vessels supplying the lungs. The clot (embolus) most often comes from the leg veins A Embolus and travels through the heart to the lungs. When the blood clot lodges in the blood vessels of the lung, it may limit the Heart heart’s ability to deliver blood to the lungs, causing shortness of breath and chest pain, and, in serious cases, death. The US surgeon general estimates that 100 000 to 180 000 deaths occur from PE each year in the United States and identifies PE 2 The embolus travels through as the most preventable cause of death among hospitalized bloodstream and heart into patients. The January 9, 2013, issue of JAMA contains an Inferior the vessels of the lung. vena cava article about management of PE. TO 1 A blood clot forms in HEART RISK FACTORS a vein and breaks free from the vessel wall. • Genetic and acquired tendencies to develop blood clots • Free blood clot Pregnancy; use of birth control pills or hormone therapy Femoral Vein (embolus) • Obesity vein • Smoking Blood clot • Cancer • Medical illnesses including heart disease, lung disease, and kidney disease Valve • Older age • Recent surgery, trauma, hospitalization, or prolonged bed rest SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS FOR MORE INFORMATION • Shortness of breath • Palpitations • American Venous Forum • Chest discomfort • Dizziness and fainting www.veinforum.org • Coughing up blood • Leg swelling and discomfort • North American Thrombosis Forum www.NATFonline.org TREATMENT INFORM YOURSELF Anticoagulants (commonly called blood thinners) are the main treatment for pulmonary embolism and work by preventing new blood clots from forming while the To find this and previous JAMA body breaks down the pulmonary embolism. -

Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary Embolism Pulmonary Embolism (PE) is the blockage of one or more arteries in the lungs, ultimately eliminating the oxygen supply causing heart failure. This can take place when a blood clot from another area of the body, most often from the legs, breaks free, enters the blood stream and gets trapped in the lung's arteries. Once a clot is lodged in the artery of the lung, the tissue is then starved of fuel and may die (pulmonary infarct) or the blockage of blood flow may result in increased strain on the right side of the heart. It is estimated that approximately 600,000 patients suffer from pulmonary embolism each year in the US. Of these 600,000, 1/3 will die as a result. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is the most common precursor of pulmonary embolism. With early treatment of DVT, patients can reduce their chances of developing a life threatening pulmonary embolism to less than one percent. Early treatment with blood thinners is important to prevent a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, but does not treat the existing clot in the leg. Get more information on Deep Vein Thrombosis. Symptoms of PE Symptoms of pulmonary embolism can include shortness of breath; rapid pulse; sweating; sharp chest pain; bloody sputum (coughing up blood); and fainting. These symptoms are frequently nonspecific to pulmonary embolism and can mimic other cardiopulmonary events. Since pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening, if any of these symptoms are present please see your physician immediately. Treatments for PE Anticoagulation The first line of defense when treating pulmonary embolism is by using an anticoagulant. -

Status Epilepticus Due to Cerebral Air Embolism After the Valsalva Maneuver CASE REPORT

eISSN 2508-1349 J Neurocrit Care 2019;12(1):51-54 https://doi.org/10.18700/jnc.190075 Status epilepticus due to cerebral air embolism after the Valsalva maneuver CASE REPORT Hyun Ji Lyou, MD; Hye Jeong Lee, MD; Grace Yoojin Lee, MD; Received: March 11, 2019 Won-Joo Kim, MD, PhD Revised: May 3, 2019 Accepted: May 27, 2019 Department of Neurology, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea Corresponding Author: Won-Joo Kim, MD Department of Neurology, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, 211 Eonju-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 06273, Republic of Korea Tel: +82-2-2019-3324 Fax: +82-2-3462-5904 E-mail: [email protected] Background: Cerebral air embolism is uncommon but potentially causes catastrophic events such as cardiac damage or even death. However, due to a low overall incidence, it may go undiagnosed. Case Report: A 56-year-old man with a medical history of right upper lobectomy due to lung cancer showed changes in mental status after the Valsalva maneuver, followed by status epilepticus during admission. Brain and chest computed tomography showed cerebral air embolism and accidental pneumothorax in the right major fissure. After antiepileptic drug infusion and oxygen therapy, he recov- ered completely. Conclusion: Since cerebral air embolism may result in fatal outcomes, it should be suspected in patients with sudden neurological de- terioration after routine medical procedures. Keywords: Status epilepticus; Embolism, air; Pneumothorax; Valsalva maneuver INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT Cerebral air embolism is a rare but potentially severe complication A 56-year-old man with a medical history of right upper lobectomy of iatrogenic procedures or destructive lung disease, possibly re- due to lung cancer presented to the emergency room with changes sulting in neurological disorders such as encephalopathy, stroke, or in mental status after the Valsalva maneuver during a pulmonary seizure. -

Chapter 6: Clinical Presentation of Venous Thrombosis “Clots”

CHAPTER 6 CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF VENOUS THROMBOSIS “CLOTS”: DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS AND PULMONARY EMBOLUS Original authors: Daniel Kim, Kellie Krallman, Joan Lohr, and Mark H. Meissner Abstracted by Kellie R. Brown Introduction The body has normal processes that balance between clot formation and clot breakdown. This allows clot to form when necessary to stop bleeding, but allows the clot formation to be limited to the injured area. Unbalancing these systems can lead to abnormal clot formation. When this happens clot can form in the deep veins usually, but not always, in the legs, forming a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). In some cases, this clot can dislodge from the vein in which it was formed and travel through the bloodstream into the lungs, where it gets stuck as the size of the vessels get too small to allow the clot to go any further. This is called a pulmonary embolus (PE). This limits the amount of blood that can get oxygen from the lungs, which then limits the amount of oxygen that can be delivered to the rest of the body. How severe the PE is for the patient has to do with the size of the clot that gets to the lungs. Small clots can cause no symptoms at all. Very large clots can cause death very quickly. This chapter will describe the symptoms that are caused by DVT and PE, and discuss the means by which these conditions are diagnosed. What are the most common signs and symptoms of a DVT? The symptoms that are caused by DVT depend on the location and extent of the clot. -

Hypercoagulability in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia With

Published online: 2019-09-26 Case Report Hypercoagulability in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with epilepsy Josef Finsterer, Ernst Sehnal1 Departments of Neurological and 1Cardiology and Intensive Care Medicine, General Hospital Rudolfstiftung, Vienna, Austria, Europe ABSTRACT Recent data indicate that in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia (HHT), low iron levels due to inadequate replacement after hemorrhagic iron losses are associated with elevated factor‑VIII plasma levels and consecutively increased risk of venous thrombo‑embolism. Here, we report a patient with HHT, low iron levels, elevated factor‑VIII, and recurrent venous thrombo‑embolism. A 64‑year‑old multimorbid Serbian gipsy was diagnosed with HHT at age 62 years. He had a history of recurrent epistaxis, teleangiectasias on the lips, renal and pulmonary arterio‑venous malformations, and a family history positive for HHT. He had experienced recurrent venous thrombosis (mesenteric vein thrombosis, portal venous thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis), insufficiently treated with phenprocoumon during 16 months and gastro‑intestinal bleeding. Blood tests revealed sideropenia and elevated plasma levels of coagulation factor‑VIII. His history was positive for diabetes, arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, cerebral abscess, recurrent ischemic stroke, recurrent ileus, peripheral arterial occluding disease, polyneuropathy, mild renal insufficiency, and epilepsy. Following recent findings, hypercoagulability was attributed to the sideropenia‑induced elevation -

Brachial Artery Embolus Mimicking Acute Stroke Christine Holmstedt and Marc Chimowitz Neurology 2011;76;E86-E87 DOI 10.1212/WNL.0B013e3182190cc0

RESIDENT & FELLOW SECTION E-Pearl: Section Editor Brachial artery embolus mimicking acute Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, MS stroke Christine Holmstedt, DO PEARL paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, hypertension, dyslipi- Marc Chimowitz, • Limb arterial embolism should be considered in demia, congestive heart failure, and coronary artery MBChB the differential diagnosis of acute monoparesis disease. The patient was not anticoagulated because because the diagnosis may be missed if the of a recent gastrointestinal bleeding episode. other typical manifestations of this presentation The emergency department physician diagnosed Address correspondence and (pain, pallor, pulselessness, sensory loss, and acute stroke and requested a telemedicine consulta- reprint requests to Dr. Christine tion. The patient’s blood pressure was 160/70 mm Holmstedt, Harborview Office coolness of the arm) are overlooked. Although Tower, 19 Hagwood Ave., MSC the rapid identification of acute ischemic stroke Hg, and a rhythm strip demonstrated normal sinus 805, Medical University of South rhythm at 80 beats per minute. On neurologic exam- Carolina, Charleston, SC 29464 is essential to the timely delivery of thrombolyt- [email protected] ics, care must be taken to obtain the relevant ination, the right upper extremity strength revealed history and to ensure that important signs are no effort against gravity with some preserved not missed whether the evaluation of the pa- strength in wrist and finger extension. The patient tient is done at the bedside or by telemedicine. could not localize touch on the right arm. Findings • Rapid and accurate diagnosis of ischemic stroke from the remainder of the neurologic examination, is essential for timely and appropriate treatment including speech and language, cranial nerves, coor- with thrombolytic therapy. -

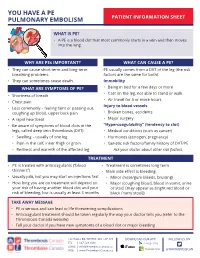

You Have a Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

YOU HAVE A PE PULMONARY EMBOLISM PATIENT INFORMATION SHEET WHAT IS PE? • A PE is a blood clot that most commonly starts in a vein and then moves into the lung. WHY ARE PEs IMPORTANT? WHAT CAN CAUSE A PE? • They can cause short term and long-term PE usually comes from a DVT of the leg (the risk breathing problems. factors are the same for both). • They can sometimes cause death. Immobility WHAT ARE SYMPTOMS OF PE? • Being in bed for a few days or more • Cast on the leg, not able to stand or walk • Shortness of breath • Air travel for 6 or more hours • Chest pain Injury to blood vessels • Less commonly – feeling faint or passing out, coughing up blood, upper back pain • Broken bones, accidents • A rapid heartbeat • Major surgery • Be aware of symptoms of blood clots in the “Hypercoagulability” (tendency to clot) legs, called deep vein thrombosis (DVT): • Medical conditions (such as cancer) • Swelling – usually of one leg • Hormones (estrogen, pregnancy) • Pain in the calf, inner thigh or groin • Genetic risk factors/family history of DVT/PE • Redness and warmth of the affected leg Ask your doctor about other risk factors. TREATMENT • PE is treated with anticoagulants (“blood • Treatment is sometimes long term thinners”) • Main side effect is bleeding: • Usually pills, but you may start on injections first • Minor (nose/gum bleeds, bruising) • How long you are on treatment will depend on • Major (coughing blood, blood in vomit, urine your risk of having another blood clot and your or stool [may appear as bright red blood or risk of bleeding, but is usually at least 3 months black / tarry stool]) TAKE AWAY MESSAGE • PE is serious and can lead to life threatening complications • Anticoagulant treatment should be taken regularly the way your doctor tells you (refer to the Thrombosis Canada website) • Tell your doctor if you have new symptoms of a blood clot or major bleeding 128 HALLS RD, WHITBY, ON, L1P 1Y8 DOWNLOAD OUR APP FOLLOW US ON TEL | 647-528-8586 EMAIL | [email protected] WEB | www.ThrombosisCanada.ca @THROMBOSISCAN. -

A Mechanistic Model for Atherosclerosis and Its Application to the Cohort of Mayak Workers

RESEARCH ARTICLE A mechanistic model for atherosclerosis and its application to the cohort of Mayak workers Cristoforo Simonetto1*, Tamara V. Azizova2, Zarko Barjaktarovic1, Johann Bauersachs3, Peter Jacob1¤, Jan Christian Kaiser1, Reinhard Meckbach1, Helmut SchoÈ llnberger1, Markus EidemuÈ ller1 1 Helmholtz Zentrum MuÈnchen, Department of Radiation Sciences, Neuherberg, Germany, 2 Southern Urals Biophysics Institute, Ozyorsk, Chelyabinsk Region, Russia, 3 Hannover Medical School, Department of Cardiology and Angiology, Hannover, Germany a1111111111 a1111111111 ¤ Current address: RADRISK, Schliersee, Germany * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract We propose a stochastic model for use in epidemiological analysis, describing the age- dependent development of atherosclerosis with adequate simplification. The model features OPEN ACCESS the uptake of monocytes into the arterial wall, their proliferation and transition into foam Citation: Simonetto C, Azizova TV, Barjaktarovic Z, cells. The number of foam cells is assumed to determine the health risk for clinically relevant Bauersachs J, Jacob P, Kaiser JC, et al. (2017) A events such as stroke. In a simulation study, the model was checked against the age-depen- mechanistic model for atherosclerosis and its dent prevalence of atherosclerotic lesions. Next, the model was applied to incidence of ath- application to the cohort of Mayak workers. PLoS ONE 12(4): e0175386. https://doi.org/10.1371/ erosclerotic stroke in the cohort of male workers from the Mayak nuclear facility in the journal.pone.0175386 Southern Urals. It describes the data as well as standard epidemiological models. Based on Editor: Xianwu Cheng, Nagoya University, JAPAN goodness-of-fit criteria the risk factors smoking, hypertension and radiation exposure were tested for their effect on disease development. -

Real-World Data from the Gemelli Hospital HHT Registry

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Antithrombotic Therapy in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: Real-World Data from the Gemelli Hospital HHT Registry Eleonora Gaetani 1,2,*, Fabiana Agostini 1,2, Igor Giarretta 1,2 , Angelo Porfidia 1,3 , Luigi Di Martino 1,2, Antonio Gasbarrini 1,2, Roberto Pola 1,4 1, and on behalf of the Multidisciplinary Gemelli Hospital Group for HHT y 1 Multidisciplinary Gemelli Hospital Group for HHT, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (F.A.); [email protected] (I.G.); angelo.porfi[email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (L.D.M.); [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (R.P.) 2 Department of Translational Medicine and Surgery, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy 3 Division of Internal Medicine, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy 4 Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-06-30157075 Multidisciplinary Gemelli Hospital Group for HHT: Giulio C. Passali, Maria E. Riccioni, Annalisa Tortora, y Veronica Ojetti, Daniela Feliciani, Leonardo Stella, Clara De Simone, Luigi Corina, Alfredo Puca, Carmelo L. Sturiale, Laura Riccardi, Aldobrando Broccolini, Carmine Di StasiAndrea Contegiacomo, Annemilia Del Ciello, Pietro M. Ferraro, Emanuela Lucci-Cordisco, Giuseppe Zampino, Valentina Giorgio, Giuseppe Marrone, Gabriele Spoletini, Gabriella Locorotondo, Gaetano Lanza, Erica De Candia, Elisabetta Peppucci, Marianna Mazza, Giuseppe Marano, Maria T. Lombardi, Maria G.