Fishery Management Plan Final Environmental Impact Statement April 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHERE DO SAWFISH LIVE? Educator Information for Student Activity 4

WHERE DO SAWFISH LIVE? Educator Information For Student Activity 4 Lesson Summary: This lesson examines the diversity of locations and habitats where sawfish are found throughout the world. Vocabulary: Distribution, habitats Background Information: There are six recognized species of sawfish throughout the world. In this activity the distribution range of each species will be discussed and mapped. Information on each species can be found in the “Sawfish In Peril” teaching binder within each of the species profiles. Materials: Copies of activity map sheets and species profile laminated cards w/maps Pencils: colored pencils recommended Procedure: This activity begins by getting students to look at the different maps of sawfish species distribution. Have each student color in a map template of the distribution of a favorite sawfish species or have students form groups to color the maps for each species. Discussion Questions: Where do sawfish live? What habitats do sawfish reside in? Where would you go if you wanted to see a sawfish? Extension Activities: For more advanced students, the following questions can be discussed: What determines where sawfish species live? Do sawfish prefer certain water temperatures and habitat types? In the past, did sawfish have larger distribution then they do currently? If so, why do you think that is? www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish 6-14 © 2010 Florida Museum of Natural History WHERE DO SAWFISH LIVE? Educator Information For Student Activity 4 Maps of sawfish species geographical distribution (from the species profiles): Smalltooth Sawfish (P. pectinata) Freshwater Sawfish (P. microdon) Largetooth Sawfish (P. perotteti) Dwarf Sawfish (P. clavata) Green Sawfish (P. -

Life History of the Critically Endangered Largetooth Sawfish: a Compilation of Data for Population Assessment and Demographic Modelling

Vol. 44: 79–88, 2021 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published January 28 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01090 Endang Species Res OPEN ACCESS Life history of the Critically Endangered largetooth sawfish: a compilation of data for population assessment and demographic modelling P. M. Kyne1,*, M. Oetinger2, M. I. Grant3, P. Feutry4 1Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Northern Territory 0909, Australia 2Argus-Mariner Consulting Scientists, Owensboro, Kentucky 42301, USA 3Centre for Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture and College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia 4CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Hobart, Tasmania 7000, Australia ABSTRACT: The largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis is a Critically Endangered, once widespread shark-like ray. The species is now extinct or severely depleted in many former parts of its range and is protected in some other range states where populations persist. The likelihood of collecting substantial new biological information is now low. Here, we review all available life history infor- mation on size, age and growth, reproductive biology, and demography as a resource for popula- tion assessment and demographic modelling. We also revisit a subset of historical data from the 1970s to examine the maternal size−litter size relationship. All available information on life history is derived from the Indo-West Pacific (i.e. northern Australia) and the Western Atlantic (i.e. Lake Nicaragua-Río San Juan system in Central America) subpopulations. P. pristis reaches a maxi- mum size of at least 705 cm total length (TL), size-at-birth is 72−90 cm TL, female size-at-maturity is reached by 300 cm TL, male size-at-maturity is 280−300 cm TL, age-at-maturity is 8−10 yr, longevity is 30−36 yr, litter size range is 1−20 (mean of 7.3 in Lake Nicaragua), and reproductive periodicity is suspected to be biennial in Lake Nicaragua (Western Atlantic) but annual in Aus- tralia (Indo-West Pacific). -

Fishing Programme Questionnaire

T H E F LYDRESSERS ’ G UILD Sussex Branch Newsletter JT AH E N F ULYDRESSERS A R Y 2’G 0UILD2 0 Lower Itchen Fishery report When I was offered the choice of the weekday or weekend trip, I opted for the weekday one. I By Andy Wood reasoned that the fishery would be quieter, but completely overlooked the travel implications. From a journey perspective it was, of course, anything but quiet on a workday morning. There was some sort of issue on the M27 that reduced traffic to a crawl, increasing the journey time to almost two and a half hours. However, on arriving at the fishery and seeing the river for the first time, that all became a distant memory. Despite the recent wet weather, the river was running crystal clear and the sun was shining, with virtually no wind. Probably less than perfect conditions for fishing, but one of those days when it’s simply sufficient to be out there and taking it all in. After a challenging drive up river – it felt like I was in it at times - where I got to I’ve wanted to fish the Lower Itchen for a while wondering whether my breakdown cover would because I love chalk streams. Before starting extend to some river bank in the middle of out fly fishing I always had that classic image in nowhere, we arrived at the ‘fly only’ stretch and my head that such rivers represented the parked up pinnacle of the sport. This was at least in part I quickly got my gear together, while taking in a down to the fact that for 5 wonderful years I was couple of tips from Ray, and the four of us went lucky enough to live within walking distance of our separate ways in pursuit of the ‘Lady of the the Upper Avon at Durrington, just off the Stream’. -

2020 Journal

THE OFFICIAL Supplied free to members of GFAA-affiliated clubs or $9.95 GFAA GAMEFISHING 2020 JOURNAL HISTORICAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA 2020 JOURNAL THE OFFICIAL GAME FISHING ASSOCIATION SPECIAL FEATURE •Capt Billy Love – Master of Sharks Including gamefish weight gauges, angling Published for GFAA by rules/regulations, plus GFAA and QGFA records www.gfaa.asn.au LEGENDARY POWER COUPLE THE LEGEND CONTINUES, THE NEW TEREZ SERIES OF RODS BUILT ON SPIRAL-X AND HI-POWER X BLANKS ARE THE ULTIMATE SALTWATER ENFORCER. TECHNOLOGY 8000HG MODELS INFINITE POWER CAST 6’6” HEAVY 50-150lb SPIN JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg CAST 6’6” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg THE STELLA SW REPRESENTS THE PINNACLE OF CAST 6’6” XX-HEAVY 80-200lb SPIN JIG 5’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 24-37kg SHIMANO TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION IN THE CAST 7’0” MEDIUM 30-65lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’10” MEDIUM 24kg PURSUIT OF CREATING THE ULTIMATE SPINNING REEL. CAST 7’0” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb OVERHEAD JIG 5’8” HEAVY 37kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM 20-50lb SPIN 7’6” MEDIUM 10-15kg SPIN 6’9” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb SPIN 7’6” HEAVY 15-24kg TECHNOLOGY SPIN 6’9” HEAVY 50-100lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM 5-10kg SPIN 6’9” X-HEAVY 65-200lb SPIN 7’0” MEDIUM / LIGHT 8-12kg UPGRADED DRAG WITH SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / LIGHT 15-40lb SPIN 7’9” STICKBAIT PE 3-8 HEAT RESISTANCE SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM lb20-50lb SPIN 8’0” GT PE 3-8 *10000 | 14000 models only SPIN 7’2” MEDIUM / HEAVY 40-80lb Check your local Shimano Stockists today. -

Smalltooth Sawfish Programmatic FPR-2017-9236

NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE ENDANGERED SPECIESACT SECTION 7 BIOLOGICAL OPINION Title: Biological Opinion on the Smalltooth Sawfish(Pristis pectinata) Research Permit Program Consultation Conducted By: EndangeredSpecies Act Interagency Cooperation Division, Officeof Protected Resources, National Marine Fisheries Service Action Agency: Permits and Conservation Division, Officeof Protected Resources, National Marine Fisheries Service Publisher: Officeof Protected Resources, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanicand Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce Approved: , Donna S. Wieting Director, Officeof Protected Resour s FEB 1 4 2019 Date: Consultation Tracking Number: FPR-2017-9236 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.25923 This page left blank intentionally Smalltooth sawfish programmatic FPR-2017-9236 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Consultation History ............................................................................................... 2 2 Description of the Proposed Action ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Application Submission and Review ...................................................................... 5 2.2 Analysis and Decision Making .............................................................................. -

Searching for Responsible and Sustainable Recreational Fisheries in the Anthropocene

Received: 10 October 2018 Accepted: 18 February 2019 DOI: 10.1111/jfb.13935 FISH SYMPOSIUM SPECIAL ISSUE REVIEW PAPER Searching for responsible and sustainable recreational fisheries in the Anthropocene Steven J. Cooke1 | William M. Twardek1 | Andrea J. Reid1 | Robert J. Lennox1 | Sascha C. Danylchuk2 | Jacob W. Brownscombe1 | Shannon D. Bower3 | Robert Arlinghaus4 | Kieran Hyder5,6 | Andy J. Danylchuk2,7 1Fish Ecology and Conservation Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology and Recreational fisheries that use rod and reel (i.e., angling) operate around the globe in diverse Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary freshwater and marine habitats, targeting many different gamefish species and engaging at least Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, 220 million participants. The motivations for fishing vary extensively; whether anglers engage in Ontario, Canada catch-and-release or are harvest-oriented, there is strong potential for recreational fisheries to 2Fish Mission, Amherst, Massechussetts, USA be conducted in a manner that is both responsible and sustainable. There are many examples of 3Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, Uppsala University, Visby, recreational fisheries that are well-managed where anglers, the angling industry and managers Gotland, Sweden engage in responsible behaviours that both contribute to long-term sustainability of fish popula- 4Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, tions and the sector. Yet, recreational fisheries do not operate in a vacuum; fish populations face Leibniz-Institute -

Smalltooth Sawfish in Coastal Waters

Smalltooth Sawfish: a large yet little-known fish in local coastal waters History “Mangroves provide crucial habitat for young sawfish Rookery Bay Research For most people, seeing a sawfish is not an everyday Baby sawfish (neonates) and juveniles are extremely vulnerable to predators occurrence, in fact, most folks don’t even know to avoid predators.” -- George Burgess such as crocodiles, sharks and even dolphins, which is why the protective they exist in Florida. They are nowhere near as shelter provided by mangrove estuaries is so important. Plus, estuaries provide numerous as they used to be, and their range has a very productive food resource of small invertebrates and fish. been reduced significantly, but sawfish seem to be maintaining a small core population along the Conservation Measures Reserve biologist Pat O’Donnell knows southwest Florida coast. firsthand that the mangrove estuaries The smalltooth sawfish, Pristus pectinata, was reported in 1895 as regionally in the Rookery Bay Reserve are good abundant throughout coastal Florida, including in the Indian River Lagoon In June the Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research habitat for young sawfish. Since which was historically known as an aggregation area. It wasn’t until 1981 that Reserve’s “Summer of Sharks” lecture series 2000, when he began monthly shark scientists recognized the significance of the sawfish’s disappearance from there welcomed George Burgess, curator of the National research, O’Donnell has captured, and blamed it on habitat degradation from development. Conservation efforts Sawfish Encounter Database from the University documented and released more than came too late for the largetooth sawfish, Pristus perotetti, which was last seen of Florida. -

Inside This Issue

Website: www.wffc.com Member of MMXXI No. 2 February, 2021 2021 WFFC Budget. President’s What to go fishing? Dave Schorsch will begin pub- Riffle lishing a monthly “Do-it-Yourself” Outing recommen- Have you got your dation until we can start holding Club Outings once vaccination shot yet? again. His first DIY fishing opportunities overview is Being in the B1 age included in this Creel Notes edition [pages 4 & 5] and group, I have had my it is terrific! first shot and will get I hope to see you all at the February 16th Zoom my second shot later Monthly Meeting. At that meeting I will give a short this month. Hopefully all of you will be able to receive report on what the outlook for the club to resume your shot(s) by the end of this summer so we may be in person Dinner Meetings, Outings and Education able to get together once again to go “fishing” in the Classes this year. Following the business part of our Fall and hold the Christmas Holiday Fundraiser in meeting, David Williams will be the zoom meeting’s December. speaker and will talk to us about the where and how to At the February 2nd Board Meeting, the proposed catch bass in Eastern Washington. 2021 WFFC Revenue and Expenses Budget was pre- Don’t forget to pay your 2021 WFFC Dues, they are sented and approved by the Board. It will be presented only $40 this year! to the membership for approval or rejection by an Stay Safe, get your vaccine shot and Tight Lines - emailed ballot at the end of this month, per the WFFC Jim Goedhart WFFC President Bylaws requirements. -

Regulations in Belize

! ! "#$%&'($)&'*'(!+*,)&%*&,!-.'.(&/&'$!*'!012! 134'$%*&,"!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! ! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Final Technical Report SUPPORT TO UPDATE THE FISHERIES REGULATIONS IN BELIZE REFERENCE: CAR/1.2/3B Country: Belize 29 November 2013 Assignment implemented by Poseidon Aquatic Resources Management i Project Funded by the European Union. “This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of ”name of the author” and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.” “The content of this document does not necessarily reflect the views of the concerned governments.” SUPPORT TO UPDATE THE FISHERIES REGULATIONS IN BELIZE Contents CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................... I! LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND PHOTOGRAPHS .................................................................................. II! LIST OF APPENDICES ......................................................................................................................... III! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................................... IV! ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .................................................................................................... -

Storm-Tide Elevations Produced by Hurricane Andrew Along the Southern Florida Coasts, August 24,1992

Storm-Tide Elevations Produced by Hurricane Andrew Along the Southern Florida Coasts, August 24,1992 By MITCHELL H. MURRAY U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 94-116 Prepared in cooperation with the Federal Emergency Management Agency Tallahassee, Florida 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GORDON P. EATON, Director For additional information, write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center Suite 3015 Open-File Reports Section 227 N. Bronough Street Box 25286, MS 517 Tallahassee, FL 32301 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract......................-. ......... ....-.. .................. Introduction.............................................................................................................................^ Description of study area.............................................................................................................................4 Methods.........................................................................................................................................................^ Vertical datum...............................................................................................................................................6 Acknowledgments.............................................................................................. .......................................8 Storm-tide elevations...............................................................................................................................................8 -

A Practical Key for the Identification of Large Fish Rostra 145-160 ©Zoologische Staatssammlung München/Verlag Friedrich Pfeil; Download

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Spixiana, Zeitschrift für Zoologie Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 038 Autor(en)/Author(s): Lange Tabea, Brehm Julian, Moritz Timo Artikel/Article: A practical key for the identification of large fish rostra 145-160 ©Zoologische Staatssammlung München/Verlag Friedrich Pfeil; download www.pfeil-verlag.de SPIXIANA 38 1 145-160 München, August 2015 ISSN 0341-8391 A practical key for the identification of large fish rostra (Pisces) Tabea Lange, Julian Brehm & Timo Moritz Lange, T., Brehm, J. & Moritz, T. 2015. A practical key for the identification of large fish rostra (Pisces). Spixiana 38 (1): 145-160. Large fish rostra without data of origin or determination are present in many museum collections or may appear in customs inspections. In recent years the inclu- sion of fish species on national and international lists for the protection of wildlife resulted in increased trading regulations. Therefore, useful identification tools are of growing importance. Here, we present a practical key for large fish rostra for the families Pristidae, Pristiophoridae, Xiphiidae and Istiophoridae. This key allows determination on species level for three of four families. Descriptions of the rostrum characteristics of the respective taxa are given. Tabea Lange, Lindenallee 38, 18437 Stralsund Julian Brehm, Königsallee 5, 95448 Bayreuth Timo Moritz, Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Polyodon spathula is equipped with a spoon-like rostrum which is used as an electrosensory organ Rostra are found in many fish species and can for locating plankton in water columns (Wilkens & be used for hunting (Wueringer et al. -

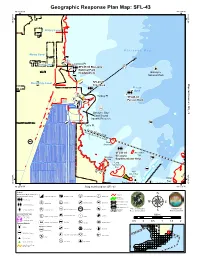

Sfl-43 80°22'30"W 80°15'0"W 25°30'0"N 25°30'0"N

Geographic Response Plan Map: SFL-43 80°22'30"W 80°15'0"W 25°30'0"N 25°30'0"N Military Canal Biscayne Homestead Air Reserve Base National Park Biscayne Bay Biscayne Bay Mowry Canal # d(!S XXX North Canal ! Convoy Pt XXXSFL43-04 Biscayne !(R # National Park j Headquarters Biscayne !(h National Park SFL43-01 Map continued on:SFL-44 Florida City Canal 1600 Croc Area XXX Pelican XXX Bank !(S Turkey Pt d SFL43-02 !( !d # Pelican Bank !q k Biscayne Bay/ h Card Sound !( Aquatic Preserve !d !(h Turtle Pt Sector Miami AOR Sector Key West AOR Adams West Key Arsenicker XXX SFL43-03 Arsenicker Biscayne Key Mangrove ][ XXX Point Bay/Arsenicker Keys C Long a esa Arsenicker r Key h Cr !( Sector Miami AOReek East Sector Key West AOR Arsenicker Key Totten Totten Key Key East Arsenicker Key j 25°22'30"N Cutter 25°22'30"N Biscayne Bank XX 80°22'30"W Map continued on: SFL-41 Little 80°15'0"W National SFL41-01 Totten Key Legend Park Cutter Jones Lagoon Environmentally Sensitive Areas Mangroves Bank Summer Protection Priority Incident Command Post ][ American Crocodile ^ CoralR Reef Monitoring Site h Naval Facility ! R ! Sea Turtle O O Nesting Beach Old Rhodes Key Biscayne A - Protect First A XXX i A m st Federal Managed Areas National Park Staging Areas y[ Aquaculture b[ Evergladese Snail Kite «[ Piping Plover Swan Key ia B - Protect after A Areas !(S W State Managed Areas XX k M y r e State Waters/County Line o Cr State Park/Aquatic Preserve t K Rice Rat Fish and Wildlife d eek Florida Keys C - Protect after B Areas Florida Panther [ USCG Sector a Oil Spill