Exotic Invaders Gain Foraging Benefits by Shoaling with Native Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphological and Genetic Comparative

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 373- 383, 2008 Morphological and genetic comparative analyses of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) from Central Mexico, with description of a new species Análisis comparativo morfológico y genético de diferentes poblaciones de Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) del Centro de México, con la descripción de una especie nueva Domínguez-Domínguez Omar1*, Pérez-Rodríguez Rodolfo1 and Doadrio Ignacio2 1Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Fuente de las Rosas 65, Fraccionamiento Fuentes de Morelia, 58088 Morelia, Michoacán, México 2Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, España. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. A genetic and morphometric study of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Bean, 1898) from the Lerma and Ameca basins and Cuitzeo, Zacapu and Chapala Lakes in Central Mexico was conducted. For the genetic analysis, 7 populations were sampled and 2 monophyletic groups were identifi ed with a genetic difference of DHKY= 3.4% (3-3.8%), one being the populations from the lower Lerma basin, Ameca and Chapala Lake, and the other populations from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes. For the morphometric analysis, 4 populations were sampled and 2 morphotypes identifi ed, 1 from La Luz Spring in the lower Lerma basin and the other from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes drainages. Using these 2 sources of evidence, the population from La Luz is regarded as a new species Zoogoneticus purhepechus sp. nov. _The new species differs from its sister species Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis_ in having a shorter preorbital distance (Prol/SL x = 0.056, SD = 0.01), longer dorsal fi n base length (DFL/SL x = 0.18, SD = 0.03) and 13-14 rays in the dorsal fi n. -

The Evolution of the Placenta Drives a Shift in Sexual Selection in Livebearing Fish

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13451 The evolution of the placenta drives a shift in sexual selection in livebearing fish B. J. A. Pollux1,2, R. W. Meredith1,3, M. S. Springer1, T. Garland1 & D. N. Reznick1 The evolution of the placenta from a non-placental ancestor causes a species produce large, ‘costly’ (that is, fully provisioned) eggs5,6, gaining shift of maternal investment from pre- to post-fertilization, creating most reproductive benefits by carefully selecting suitable mates based a venue for parent–offspring conflicts during pregnancy1–4. Theory on phenotype or behaviour2. These females, however, run the risk of mat- predicts that the rise of these conflicts should drive a shift from a ing with genetically inferior (for example, closely related or dishonestly reliance on pre-copulatory female mate choice to polyandry in conjunc- signalling) males, because genetically incompatible males are generally tion with post-zygotic mechanisms of sexual selection2. This hypoth- not discernable at the phenotypic level10. Placental females may reduce esis has not yet been empirically tested. Here we apply comparative these risks by producing tiny, inexpensive eggs and creating large mixed- methods to test a key prediction of this hypothesis, which is that the paternity litters by mating with multiple males. They may then rely on evolution of placentation is associated with reduced pre-copulatory the expression of the paternal genomes to induce differential patterns of female mate choice. We exploit a unique quality of the livebearing fish post-zygotic maternal investment among the embryos and, in extreme family Poeciliidae: placentas have repeatedly evolved or been lost, cases, divert resources from genetically defective (incompatible) to viable creating diversity among closely related lineages in the presence or embryos1–4,6,11. -

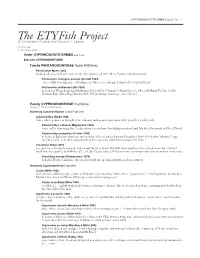

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

A New Species of Algansea (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae) from the Ameca River Basin, in Central Mexico

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 80: 483- 490, 2009 A new species of Algansea (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae) from the Ameca River basin, in Central Mexico Una especie nueva de Algansea (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae) en la cuenca del río Ameca en el centro de México Rodolfo Pérez-Rodríguez1*, Gerardo Pérez-Ponce de León2, Omar Domínguez-Domínguez3 and Ignacio Doadrio4 1Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Apartado postal 70-153, 04510, México D.F., México. 2Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Apartado postal 70-153, 04510, México D.F., México. 3Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Michoacán, México. 4Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2, 28006 Madrid, España. *Correspondencia: [email protected] Abstract. A morphological comparative analysis was performed among different populations of the cyprinid Algansea tincella Valenciennes, 1844 from the Lerma-Chapala and Ameca River basins in central Mexico. A new species, Algansea amecae n. sp. is described from individuals collected from small tributary in the headwaters of the Ameca basin. The new species differs from Lerma-Chapala populations of A. tincella by having a lower number of transversal scales, a lower number of infraorbital pores, a prominent dark lateral stripe along the body, a black caudal spot extending onto the medial caudal inter-radial membranes, and a pigmented (“dotted”) lateral line. This new species increases the high level of endemism in the freshwater ichthyofauna of the Ameca basin. It appears to be most closely related to populations in the Lerma-Chapala-Santiago system, as is the case for several other species in the Ameca basin. -

Research Article Pathology Survey on a Captive-Bred Colony of the Mexican Goodeid, Nearly Extinct in the Wild, Zoogoneticus Tequila (Webb & Miller 1998)

Hindawi Publishing Corporation The Scientific World Journal Volume 2013, Article ID 401468, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/401468 Research Article Pathology Survey on a Captive-Bred Colony of the Mexican Goodeid, Nearly Extinct in the Wild, Zoogoneticus tequila (Webb & Miller 1998) Alessio Arbuatti, Leonardo Della Salda, and Mariarita Romanucci Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Teramo, Piazza Aldo Moro 45, 64100 Teramo, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Mariarita Romanucci; [email protected] Received 21 August 2013; Accepted 18 September 2013 Academic Editors: M. Dykstra and J. L. Romalde Copyright © 2013 Alessio Arbuatti et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Mexican Goodeid, Zoogoneticus tequila, is considered nearly extinct in the wild and it is maintained in captivity by the nonprofit international “Goodeid Working Group.” The unique Italian colony has produced about 180 fish so far. The observable diseases were registered and some fish were submitted, immediately after spontaneous death, to necroscopic and histopathologic exams. Encountered diseases included the following: 7 cases of scoliosis (2 males and 5 females); 2 fish with a similar congenital deviation of ocular axis; 1 adult male with left corneal opacity, presumably of traumatic origin; 1 female fish with a large subocular fluid-filled sac, histologically referable to a lymphatic cyst, similarly to the eye sacs of a Goldfish variety (Carassius auratus)calledbubble eye; and 1 female fish with recurrent abdominal distension consequent to distal bowel dilation and thinning, associated with complete mucosal atrophy, and comparable to intestinal pseudo-obstruction syndromes described in humans and various animal species. -

Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater And

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Estado De Conservación De Los Peces De La Familia Goodeidae (Cyprinodontiformes) En La Mesa Central De México

Estado de conservación de los peces de la familia Goodeidae (Cyprinodontiformes) en la mesa central de México Marina Y. De la Vega-Salazar Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología UNAM. Dirección actual: Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario Los Lagos. Enrique Díaz de León s/n, Colonia Paseos de la Montaña Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco, México; [email protected] Recibido 10-VI-2005. Corregido 11-VIII-2005. Aceptado 15-X-2005. Abstract: Conservation status of Goodeidae familiy fishes (Cyprinodontiformes) from the Mexican Central Plateau. To establish the conservation status and threats for Goodeidae fishes in the high plateau of Mexico, I assessed limnological descriptions, and the reduction in range and in number of localities where they are found, in 53 localities (58.8% of historically reported localities). This assessment included the comparison of current collections with historical records. A principal component analysis of limnological variables showed that most remnant Goodeid species inhabit localities characterised by low environmental degradation: few appear to have a high tolerance to environmental degradation. Overall, 65% of species suffered a reduction in number of localities where they are found. Almost all species face some conservation threat, considering the criteria and categories established by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Data suggest that one species is extinct (Allotoca catarinae), one more is extinct in the wild (Skiffia francesae), eight are critically endangered (Allodontichthys hubbsi, Allotoca goslinei, Allotoca regalis, Allotoca zacapuensi, Ameca splendens, Characodon audax, Hubbsina turneri, and Zoogoneticus tequila), eleven are endangered, eight can be regarded as vulnerable, four are “near threatened” and only two appear to under “least concern”. -

Tank Topics the Official Publication of the Greater Akron Aquarium Society

Tank Topics The Official Publication of The Greater Akron Aquarium Society J u n e/ J u ly 2 0 0 9 I n t h is is s u e : Good ei d s Na n d op si s h a ti en si s O t oph a r yn x t et r a stig ma THE GREATER AKRON AQUARIUM SOCIETY WHO ARE WE? We are a local group of aquatic enthusiasts. Formed in 1952, the Greater Akron Aquarium Society is a non-profit, non-commercial organization. Our membership ranges from the beginning hobbyist to the advanced aquarist with many years of experience. The goals of our club are to promote the care, study, breeding and exhibition of aquarium related aquatic life and to promote interest in the aquarium hobby. MEETINGS: Our meetings are held on the first Thursday of each month at 8:00 p.m. at the Mogadore Community/Senior Center, 3857 Mogadore Road, Mogadore, Ohio. It is located East of Route 532 across from McDonald’s in the former post office building (see map on inside back cover) Visitors are always welcome, it costs absolutely nothing to attend a meeting and look us over. MEMBERSHIP: The cost is only $750 for adults, $10 for a couple or a family (includes children under 10 years of age) and $5.00 for a junior membership (10 to 17 years) Membership provides an opportunity to socialize with other that share your interests, a subscription to our bi-monthly magazine, library usage and more. AGENDA: Our meeting agenda is simple and informal. -

Curriculum De Boto López Luis

Luis Boto López Curriculum vitae 24/10/2019 APELLIDOS: Boto López NOMBRE: Luis FECHA DE NACIMIENTO: 5 Octubre 1955 FORMACION ACADEMICA LICENCIATURA en Ciencias Biológicas por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, año 1977. GRADO obtenido el 29 de Septiembre de 1977 en la Facultad de Biológicas de la Universidad Complutense con la calificación de Notable. DOCTORADO en Ciencias por la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid el 21 de Marzo de 1986 con la calificación de Apto cum laude. TITULO DE LA MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA: Influencia del frío sobre diversos parámetros de la actividad tiroidea en la rata. TITULO DE LA TESIS DOCTORAL: Modificación del desarrollo de Dictyostelium discoideum tras el tratamiento con Butirato sódico. CURSOS REALIZADOS: 1975-1976 Durante este periodo cursé como asignaturas extra de la licenciatura Antropología y Genética Evolutiva, ambas superadas con la calificación de Aprobado 1980 Bases moleculares de la morfogénesis y diferenciación celular (Curso de Doctorado. Fac.Med.U.A.M., varios profesores. Sobresaliente. 1981 Antibióticos: síntesis, modo de acción y resistencia (Curso de Doctorado. Fac. Ciencias U.A.M., Dr. García Ballesta. Aprobado.) Citoquímica de acidos nucleicos (Curso de Doctorado. Fac.Ciencias U.A.M. Dr. Stocker. Sobresaliente.) Introduccion a la Bioquímica del Cáncer (Curso de Doctorado Fac. Ciencias U.A.M. Dr. Nuñez de Castro. Sobresaliente.) 1982 Biología Molecular del Desarrollo (Curso de la Universidad Internacional Menéndez Pelayo. Santander. Varios profesores y dirigido por el Dr. Sebastián.) 1993 PCR Applied to Forensic Casework (Curso organizado por Pharmagen S.A. 1997 3rd Accelerating Gene Discovery and Mutation Detection (Organizado por Applied Biosystems) 2001 Jornadas sobre El Origen de las Especies (Organizadas por Cosmo Caixa) INVESTIGACION SITUACIONES PROFESIONALES. -

Paper Template

Review Article Neoplasias in fish: review of the last 20 years. A look from the pathology . ABSTRACT In fish there is an innumerable variety of neoplasias that arise essentially from all cell types. Neolasia here, we will focus on the neoplasias that appear spontaneously in these animals and will not cover the experimentally induced neoplasias and/or the animal models of neoplasias. As for diagnosis, in general, specialists in aquatic organism pathology are not so familiar with the diagnosis of neoplasias. Infectious pathology, as opposed to non-infectious pathology, is the predominant condition in this area and, of course, these are of greater importance because some infectious diseases generate great economic losses, while neoplasias are isolated pathologies, with some exceptions. In the last 20 years, 10 neoplasias in different species have been diagnosed in our laboratory, and we reported their characteristics in this paper. We also made a detailed bibliography review and observed how 90 neoplasias among 56 species of teleosteal fish were reported. Neoplasias in fish, unlike other diseases, do not generate great losses to aquaculture. However, the true value of neoplastic pathology compared is to better understand the histiogenesis and biological behavior of neoplasias in mammals and humans. Carcinogenesis is generally complex and in most neoplasias in both mammals and fish, the origin is unknown, and it seems that there are many factors that contribute to the onset and growth of neoplasias. Keywords: Neoplasia; diagnosis; histopathology; immunohistochemistry; fish.carcinogenesis 1. INTRODUCTION Neoplasia literally means "new growth" and neoplasm is the result of this new growth. The term 'tumor' originally was applied to the swelling caused by the inflammation. -

Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology the University of Michigan

OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ZOOGONETICUS TEQUILA, A NEW GOODEID FISH (CYPRINODONTIFORMES) FROM THE AMECA DRAINAGE OF MEXICO. AND A REDIAGNOSIS OF THE GENUS ABSTRACT.-Webb, S. A., and R. R. Millel: Zoogoneticus tequila, a new goodeid Jish (Cyprinodontiformes) from the Ameca drainage of Mexico, and a rediagnosis of the genus. Occ. Pap. Mus. Zool. Univ. Michigan 725:l-23, 5figs. Zoogoneticus tequila n.sp. is described from the Rio Teuchitlfin, an upper tributary to the Ameca drainage,- .Jalisco,- Mexico. The new species can be distinguished from its congener, Z. quitzoensis, by adult males having a broad, red-orange band of pigment subterminally in the caudal fin, with melanization in the caudal fin restricted to a proximal, paddle-shaped region. The dorsal and anal fins of adult males possess narrow terminal bands of light yellow color. The laterocaudal pigment bars in both sexes are much less intense and fade at a younger age. The genus Zoogoneticus is diagnosed by the presence of a membrane attaching the sixth pelvic ray to the ventral midline of the body, pigment patches on the posteroventral part of the body, two basicaudal spots that may coalesce, dorsal and anal fins of adult males with narrow terminal bands of red-orange or yellow pigment, with melanization basally, and trophotaeniae with 9 to 14 termini. Key words: Zoogoneticus, tequila, Goodeidae, systematics, Mexico. INTRODUCTION The Mesa Central of Mexico (West, 1964)contains a depauperate fauna of freshwater fishes which includes several endemic groups. The most *Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079 2 Webb and Mzller occ PUJIPI\ diverse component of this system is the Goodeidae.