Stone Working

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walls and Foundations of Historic Buildings

District of Columbia Historic Preservation Guidelines WALLS AND FOUNDATIONS OF HISTORIC BUILDINGS Government of the District of Columbia Office of Planning Historic Preservation Office 1100 4th Street, SW Suite 650 Washington, DC 20024 202-442-8800 Designs of Walls and Foundations Walls and above ground foundations are among the most important character-defining elements of historic buildings. The design of walls and foundations is influenced by the types of materials used, the location, proportions and scale of openings for doors and windows, massing and rhythm of features such as bays and porches, and details and ornamentation. The exterior walls of most free-standing buildings are also structural, that is they carry the weight of the floors and roof to the foundation. Conversely, the front and rear walls of rowhouses and other party-wall buildings are usually not load bearing; rather the side walls carry the weight of floors and roofs to foundations. Altering, repairing or replacing primary character-defining walls and foundations -those facing major public streets or sidewalks- must be carefully considered so as not to detract from a building's character. Changes to secondary non-character-defining walls and foundations (typically on the sides and rear of buildings) should also be carefully considered. Greater flexibility in selecting methods of construction and materials is possible for changes to non-character-defining than for character-defining walls and foundations. Above ground foundation walls are often visually distinguished from the main wall by a change of plane. For example, brick and stone foundation walls are often visually separated from the wall above by a belt course of molded brick or shaped stone. -

Stone Source Glossary of Terms.Indd

GLOSSARY OF TERMS This glossary provides you with commonly used terms for each of our material UPDATED ON: 9.13.2012 categories. The guide is divided into 5 sections: • Natural Stone • Porcelain tile + Ceramic tile • Glass Tile • Engineered Stone • Wood New York Boston Chicago Los Angeles New Jersey Washington DC Natural Stone Porcelain Tile Glass Tile Engineered Stone Reclaimed Wood 1 of 21 - stone source Glossary of terms GLOSSARY OF TERMS: Natural stone These are the terms most commonly used in relation to Natural Stone: Bleed Staining caused by corrosive metals, oil-based putties, mastics, caulking, or Abrasion resistance sealing compounds. The ability of a material to resist surface wear. Book Matched Absorption Layout wherein slabs are cut to create a mirror image of each other. The relative porosity of the material. Materials with low absorption will be less prone to staining. Materials with high-absorption may not be suitable for all applications, specifically kitchen countertops that come into regular contact with oils or pigmented acidic liquids such as wine or balsamic vinegar. Acid etching Materials that contain calcium or magnesium carbonate (marble, travertine, limestone and onyx) will react to acidic foods such as lemons or tomatoes. This reaction will result in a change in surface sheen, otherwise referred to as “acid etching”. Lighter stones and honed surfaces will typically diminish the appearance of acid etching. Antiqued finish Brushed finish A finish with a worn aged appearance, achieved by mechanically rubber- A smooth finish achieved by brushing a stone with a coarse rotary-type wire brushing the tile. brush. Buttering / Back buttering bullnose edge The process of slathering the back of a stone tile with thinset material to ensure (see edge profiles on page 8) proper mortar coverage. -

Final-Portafolio-2017.Pdf

ó Pacific Curbing is the leading company for Pinellas & Hillsborough area decorative concrete landscape curbing. Our decorative, stamped curbing is on the cutting edge of landscape design. 11/11/2016 2 ó Concrete curbing is a professionally installed, permanent, attractive concrete border edging that provides great additions and solutions to any landscape and serves as a weed and grass barrier by outlining flowerbeds. Pacific Curbing decorative concrete curbing can be installed around trees, flowerbeds, sidewalks and just about anywhere you like. 11/11/2016 3 ó Concrete curbing can enhance your landscape, it is the half of price of bricks and is a permanent solution, increase curb appeal, decrease the time spent trimming around landscape beds and increase your property value. 11/11/2016 4 ó Rollers are a soft textures impresions on the concrete curbing for the angle mold 6x4. ó You can choose a natural looking like stone or you can choose something symetrical. ó Price per foot $5.75 ó You can choose any color up 3lb ó Project is seal with the UV Sealer. ó PSI 3600 Ashlar Basketweave Brick Bone Cobblestone Flagstone H Brick Herringbone Offset bond Old stone Pebblestone Random Riverstone Running bond L Running bond Slate Spanish Texture Treebark Wood RAMDOM ROLLER RUNNING BOND ROLLER SLATE ROLLER FLAGSTONE ROLLER SPANISH TEXTURE SINGLE BRICK ó Stamps are deep impresions on the concrete curbing for the angle mold 6x4. ó They come on a symetrical designs. ó Price per foot $6 ó You can choose any color up 3lb ó Project is seal with the UV Sealer. -

How to Install Dry-Laid Flagstone Complete Step by Step “How-To

How To Install Dry-Laid Flagstone Patio or Walkway Complete step by step “How-to” guide for building a dry-laid patio or walkway. Copyright © 2012 Stone Plus, Inc. How To Build A Dry Laid Flagstone Patio or Walkway As there is no single “right way” to install dry laid flagstone, we have found the following to be a solid tech- nique. Choosing Your Stone Stone for walkways and patios come in many colors, shapes, textures and sizes. When selecting the stone for your pavement, keep in mind the concept, or idea, that form fits function. When laying a dry laid patio, one should use a thicker stone that is 3/4” to 2-1/2” thick. Any thinner stone will be subject to cracking. Thinner stones are used when installing stone over an existing concrete slab. Pictured to the right is the Arizona Buff Patio flagstone. As you can see, this stone has irregular edges and may need fitting in order to get the look you desire. Pictured above: Buff Patio When installing a primary walkway or patio that has high traffic or is an entertainment area, thought should be given to selecting larger and flatter flagstone. Women in high heels, or the leg of a table and chair, find larger, flatter stones more compatible with their needs. When installing a “garden path or retreat”, the use of smaller, more irregular stone is appropriate. So when choosing a flagstone for your pavement, one should consider the purpose of the pavement. Consider the texture and size of the stone in relation to its intended pur- pose. -

614.252.0955 Or 800.845.7644 Visit Our Website at Oberfields.Com PAVER S • R E TAINING WALLS • PATIO STONES • ACCESSORIES

614.252.0955 or 800.845.7644 Visit our website at oberfields.com PAVER S • R E TAINING WALLS • PATIO STONES • ACCESSORIES CORPORATE OFFICE Oberfield’s is Ohio’s premier manufacturer and marketer SALES 528 London Road P.O. Box 362 of high-quality concrete masonry, landscape, sitescape and Delaware, OH 43015 614.252.0955 740.369.7644 building material products. We invite you to visit one of our 800.845.7644 Fax 740.363.7644 five showrooms or many distributors throughout the region. SALES & MANUFACTURING 1165 Alum Creek Drive Columbus, OH 43209 614.252.0955 Simply call us for a convenient location near you. Fax 614.252.5858 SALES 450 W. Fair Avenue Lancaster, OH 43130 740.653.3074 Fax 740.653.7285 SALES 1190 S. Prospect Street Marion, OH 43302 740.382.8888 Fax 740.382.3110 SALES & MANUFACTURING 980 Shawnee Road Lima, OH 45805 419.225.6761 Fax 419.225.6121 O©2009 bOberfield’s,er Inc. field’s RESIDENTIAL Walkways/Patios................................................ 2 Driveways ........................................................ 3 Steps & Stairways ............................................ 4 Fire Pits & Grills .............................................. 5 Water Features ................................................. 6 Columns & Borders ......................................... 7 Monroe Pavers ................................................. 8-9 Washington Pavers ........................................... 10-11 Washington Circle Pavers ................................. 12-13 Lincoln Pavers ................................................. -

A2 – Dressed Quarry Stone Wall

Building techniques : A2 – Dressed Quarry Stone Wall Coutry: Lebanon PRÉSENTATION Geographical Influence Definition Dressed quarry stone wall - traditional masonry tools: chisel, picks and hammers. - 4, 5, 6 faces-sometimes 2 faces - naturally squared. - stone laying with or without wedging. - stones are laid straight, same size or not. - mortar laying Environment In the MEDA area, we find dressed quarry stone in all environments: urban, rural, in mountain, plain and sea side. Its presence is generally common. In Lebanon, dressed quarry stone (Moqassab) is often used everywhere: rural environment, urban, plain, mountain and sea side. Illustrations General view: Details close-up: This project is financed by the MEDA programme of the European Union. The opinions expressed in the present document do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Union or of its member States. 1/8 A2 Lebanon – Dressed quarry stone wall CONSTRUCTION PRINCIPLE Foundations Illustrations Finding a "firm base" or “good ground” is a preliminary for the builder. If rock shows on the surface, the wall is built directly above. If not, all countries dig a small trench (~ 50 cm deep), practically never deeper than 1m. the width can be equal to the thickness of the wall above-ground, but it can also be up to twice this thickness. Combination of 2 factors : width of the trench and type of filling materials: adjustments and adaptation to each spot and ground. The materials are always stony: the trench is filled with stones, generally linked with mortar. If the module is small, the trench is broader. Several countries reported construction over ruins used as foundation. -

Hardscapes Aren't Really So Hard

Hardscapes Aren’t Really So Hard Designing with old and new hard materials to create beautiful, functional and lasting patios, walks and walls HARDSCAPING BASICS: Flatwork and Walls have similar components • Compacted sub-base. Proctor Density • Footing—concrete v. compacted • Setting Bed—mortar or sand • Veneer materials • Cap for wall, edge course for flatwork • Drainage—1/8” per foot min, french drain and weep holes for walls Off white board Hard Materials • Natural: Fieldstone, flagstone, aggregate, river slicks, etc • Manmade: Brick, concrete, tile, etc • Mortared vs dry laid Thermal bluestone flagstone treads, fieldstone riser and wall veneer Fieldstone used as wall boulders and fireplace veneer, flagstone patio dry laid with crushed slate joints Intergral color concrete patio Poured in place intergral color concrete steps, walls and patio Brick paver patio on compacted crusher run base and mortared brick veneer on grill station. Blue stone cap and adjacent patio set with mortar DESIGNING WITH HARDSCAPES • “Blending” vs “Matching” • Everything is a room or hallway • Outdoor rooms: floors, walls, ceilings • Creativity and beauty by using a few materials in new ways A range of colors in the pavers makes it easier to blend with surrounding materials Outdoor rooms have floors, walls and ceilings Use changes in material to differentiate outdoor rooms Everything is a “room” or “hallway” Avoid the ‘concrete doughnut’ pool deck by designing rooms as dominate hardscape connected by walkways PA bluestone 4 ways: You don’t have to change materials -

The Art of Stone Masonry in the Rockbridge County Area (1700 to Present)

The Art of Stone Masonry In the Rockbridge County Area (1700 to present) Steven Connett Archaeology 377 5/25/83 Dr. McDaniel The art of stone masonry in the Shenandoah valley seems to be somewhat of a mystery prior to the nineteenth century. However, as some of us have learned from the anthropology 101 course: The absence of artifacts (documents in this case) is just as important as the presence of artifacts. In order to make sure that the lack of information was not due to my possible incompetence in research, I spoke with a current day stone masoner named Alvis Reynolds. Mr. Reynolds relayed t o me that when he was trying to learn the skills of stone masonry he, too, had great difficulty in obtaining information and thus decided to teach himself this art through the process of trial and error. Although this information did not directly aid me in my research, Mr. Reynolds did provide me with a bit of information that allowed me to derive a hypothesis on why there is this unusual lack of information in this line of study. I will state my hypothesis in this paper, however, I will not be able to prove it or disprove it due to the deficiency in available information. Mr. Reynolds explained to me that in the eighteenth century there were nomadic stone masoners. These nomadic workers went from valley to valley in search of people who needed help with building their houses. Since these people did not know how to cut stone themselves (after all, stone cutting is not the type of thing that is innate to most people) they had no choice but to p~y these men for their services or go unsheltered. -

![BUIL])ING STON.E O·F WASHINGTON](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2790/buil-ing-ston-e-o%C2%B7f-washington-632790.webp)

BUIL])ING STON.E O·F WASHINGTON

BUIL])ING STON.E o·f WASHINGTON By WAYNE S. MOEN Washington Department of Conservation Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin No. 55 1967 State of Washington DANIEL J. EV ANS, Governor Department of Conservation H. MAURICE AHLQUIST, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 55 BUILDING STONE OF WASHINGTON By WAYNE S. MOEN STATE PRINTING PLANT. OLYMPI A , WASHINGTON 1967 For sale by Department Pof? ceConsl]SliARYervation, Olympia, Washington. PACIFIC NORTHWEST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION etnDTLAND. OR£00N CONTENTS Poge Introduction 7 General history .. ...... ...........................•............ 8 Production and vo lue . 10 Forms of building stone . 12 Field stone . 12 Rough building stone . 13 Rubble . • . 14 Flogging (flagstone) . 14 Ashlar . .. ......... ........ , ................. , . , . 15 Crushed stone . 16 Terrozzo . 17 Roofing granules.............. .... ..... ......... 18 Exposed aggregate . 18 Reconstituted stone . • . 19 Landscape rock . 20 Area coverage of bui Iding stone . 21 Acquisition of bui )ding stone . 22 Examination of stone deposits . 23 General quarrying methods . 24 Physical properties of building stone . 26 Strength . 26 Hardness and workabi Iity . • . 27 Color . 28 Alteration ....•...................... , ........... , . 29 Porosity and absorption ...........•. : . 31 Testing of building stone... .. .................... ................ 33 Common building stones of Washington . 34 Granite . 35 Geology and distribution . 35 Physical properties . 38 Varieties -

How to Build a Dry Stone Wall an Instructional Guide for Beginners

Do- It-Yourself: How to Build a Dry Stone Wall An instructional guide for beginners © Copyright Stephen Burton and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons License. By: Stephen T. Kane Table of Contents: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………….3 TOOLS, EQUIPMENT, AND SUPPLIES………………………4 GROUNDWORK…………….…………………………………….7 FOUNDATION…………………………………………………….8 COURSING.…………………………………………………………9 COPING.……………………………………………………………10 GLOSSARY………………………………………………………..11 Introduction: Whether for pure aesthetics or practical functionality, dry stone walls employ the craft of carefully stacking and interlocking stones without the use of mortar to form earthen boundaries, residential foundations, agricultural terraces, and rudimentary fences. If properly constructed, these creations will stand unabated for countless years, requiring only minimal maintenance and repairs. The ability to harness the land and shape it in a way that meets one’s needs through stone walling allows endless possibility and enjoyment after fundamental steps and basic techniques are learned. How to Build a Dry Stone Wall provides a comprehensive reference for beginners looking to start and finish a wall project the correct way. A list of essential resources and tools, a step-by-step guide, and illustrations depicting proper construction will allow readers to approach projects with a confidence and a precision that facilitates the creation of beautiful stonework. If any terminology poses an issue, simply reference the glossary provided in the back of the booklet. NOTE: Depending on property laws and building codes, many areas do not permit stone walls. Check with respective sources to determine if all residential rules and regulations will abide stonework. Also, before building anything on a property line, always consult your neighbor(s) and get their written consent. -

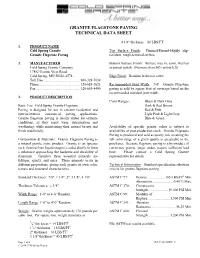

Granite Flagstone Paving Technical Data Sheet

GRANITE FLAGSTONE PAVING TECHNICAL DATA SHEET 4 1/8" thickness = 60 LBS/FT2 1. PRODUCT NAME Cold Spring Granite Top Surface Finish: Thermal/Flamed-Highly slip- Granite Flagstone Paving resistant, rough-textured surface. 2. MANUFACTURER Bottom Surface Finish: Surface may be sawn, thermal Cold Spring Granite Company or partial polish. (No more than 50% polish left) 17482 Granite West Road Cold Spring, MN 56320-4578 Edge Finish: Random broken or sawn Toll Free .......................................... 800-328-7038 Phone ............................................... 320-685-3621 Recommended Joint Width: 3/4". Granite Flagstone Fax ................................................... 320-685-8490 paving is sold by square foot of coverage based on the recommended standard joint width. 3. PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Color Ranges: Black & Dark Gray Basic Use: Cold Spring Granite Flagstone Dark & Red Brown Paving is designed for use in exterior residential and Red & Pink interior/exterior commercial paving applications. Light Pink & Light Gray Granite flagstone paving is ideally suited for extreme Blue & Green conditions, as they resist wear, deterioration and weathering, while maintaining their natural beauty and Availability of specific granite colors is subject to finish indefinitely. availability of post-production stock. Granite Flagstone Paving is produced and sold as quarry run, meaning the Composition & Materials: Granite Flagstone Paving is full color range of a given quarry is acceptable to the a natural granite stone product. Granite is an igneous purchaser. Because flagstone paving is a by-product of rock, formed from liquid magma, cooled slowly to form cut-to-size granite, larger orders require sufficient lead a substance approaching the hardness and durability of time. Please contact a Cold Spring Granite diamonds. -

Improving the Seismic Performance of Stone Masonry Buildings

A TUTORIAL: Improving the Seismic Performance of Stone Masonry Buildings Jitendra Bothara • Svetlana Brzev First Edition, July 2011 A TUTORIAL: Improving the Seismic Performance of Stone Masonry Buildings Jitendra Bothara Svetlana Brzev First Edition, July 2011 Publication Number WHE-2011-01 © 2011 Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, Oakland, California 94612-1934. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, 499 14th St., Suite 320, Oakland, CA 94612-1934. This tutorial is published by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, a nonprofit corporation. The objective of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute is to reduce earthquake risk by advancing the science and practice of earthquake engineering by improving understanding of the impact of earthquakes on the physical, social, economic, political, and cultural environment, and by advocating comprehensive and realistic measures for reducing the harmful effects of earthquakes. Production of this tutorial has been supported in part by generous contributions from the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering and the Earthquake Engineering Center of the University of Engineering and Technology, Peshawar, Pakistan. This tutorial was written and reviewed by volunteers, all of whom participate in EERI and IAEE’s World Housing Encyclopedia project. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed herein are the authors’