Comics and Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

The Daily Feather

Start Your Day with Danielle Macroeconomic Research Analysis & Insights Subscribe to The Daily Feather www.quillintelligence.com Deadpool of Labor VIPs Downward Payroll Revisions and • Powell’s characterization of the labor market being in “quite a strong Yield Curve Inversion Trending. position” defies Fed’s revision rule of thumb: three straight months Coincidence? We Think Not. of up or down revisions signal cycle turns; August marked month 120 Private Nonfarm Payroll Benchmark (avg per month, K) five, accompanied by a similar stretch of yield curve inversion Private Payroll Two-Month Revisions (sum total, K) 100 U.S. 3-month/10-year Yield Spread (bps) • Fed economists treat benchmark revisions as stronger indicators of 80 trend change vs. real time revisions with the first year of a significant benchmark revision tending to foreshadow the next; BLS private 60 payroll data was benchmark revised by -0.4%, the worst since 2010 40 • Analyzing the timeframe from January and March 2019 with the lat- 20 ter the last for which benchmark revisions are available indicates a 0 worsening trend suggesting next August’s BLS benchmark revision -20 through March 2020 will be deeper -40 -60 In Time travel has a protocol. But don’t let Deadpool 2 violating said -80 protocol, dictated by Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU —yes, there Apr MayJun JulAug SepOct NovDec Jan FebMar AprMay JunJul AugSep really is an acronym for that), dissuade you from catching the brilliant ‘18 ‘19 Source: Bloomberg, BLS, U.S. Treasury sequel to the quirkiest of all the mega-franchise’s offerings. So what if Cable, portrayed by Josh Brolin, changes the past in the present. -

2016 Spring Newsletter

Official Fan Club Site—www.juicenewtonfanclub.com 2016 Spring Newsletter Hi Everyone, The support and love for Juice has never been as powerful and as proven as it was over the last few months. This issue of the newsletter will feature some new information about Juice and will introduce you to the 2016 “O” Award winner. Paul 1 A Hit All Over Again I am pleased to announce that Juice is once again on the charts with the song that is as classy as she is. ‘Angel of The Morning’ is once again on the charts thanks to the blockbuster movie ‘Deadpool.’ (more on this later) A whole new generation of fans are listening to Juice and have joined the fan club or in- quired about the song. Congratulations Juice!! 'Deadpool' Director Tim Miller and Songwriter Chip Taylor on the Film's Soft-Rock Center- piece, 'Angel in the Morning' (http://www.billboard.com/articles/business/6882938/behind-deadpool-soundtrack-tim-miller-chiptaylor-juice-newton-angel-in-the-morning) “There'll be no strings to bind your hands / Not if my love can't bind your heart.” That’s the first thing you hear over the Marvel logo in the No. 1 movie in the country, Deadpool. As '80s pop country singer Juice Newton sings about an illicit love affair she just can’t shake in her 1981 hit “Angel of the Morning,” Ryan Reynolds’ f-bomb blasting anti-hero gets busy kicking ass. It makes zero sense on the surface, and yet director Tim Miller says that the song was the only track con- sidered to open the superhero flick that grossed another $55 million over the weekend to easily hold on to the No. -

Friday, May 18

Movies starting Friday, May 18 www.marcomovies.com America’s Original First Run Food Theater! We recommend that you arrive 30 minutes before ShowTime. “Deadpool 2” Rated R Run Time 1:20 Starring Ryan Reynolds Start 2:40 5:50 9:00 End 4:40 7:50 11:00 Rated R for strong violence and language throughout, sexual references and brief drug material. “Book Club” Rated PG-13 Run Time 1:45 Starring Diane Keaton, Jane Fonda and Candice Bergen Start 2:40 5:40 8:45 End 4:35 7:35 10:35 Rated PG-13 for sex-related material throughout, and for language. “Avengers: Infinity War” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:30 Starring Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans and Chris Hemsworth Start 2:15 5:30 8:45 End 4:45 8:00 11:15 Rated PG-13 for intense sequences of sci-fi violence and action throughout, language and some crude references. “Life of the Party” Rated PG-13 Run Time 1:45 Starring Melissa McCarthy Start 2:50 5:50 9:00 End 4:35 7:35 10:45 Rated PG-13 for suggestive material, partial nudity and some language. ***Prices*** Adults $13.00 (3D $16.50) Matinees, Seniors and Children under 12 $10.50 (3D $13.50) Visit Marco Movies at www.marcomovies.com facebook.com/MarcoMovies Deadpool 2 (R) • Ryan Reynolds • Foul-mouthed mutant mercenary Wade Wilson (AKA. Deadpool), brings together a team of fellow mutant rogues to protect a young boy of supernatural abilities from the brutal, time-traveling mutant, Cable. Book Club (PG-13) • Diane Keaton • Jane Fonda • Candice Bergen • Diane (Diane Keaton) is recently widowed after 40 years of marriage. -

Tiadventureland-Manual

Texas Instruments Home Computer ADVENTURE Overview Author: Adventure International Language: TI BASIC Hardware: TI Home Computer TI Disk Drive Controller and Disk Memory Drive or cassette tape recorder Adventure Solid State Software™ Command Module Media: Diskette and Cassette Have you ever wanted to discover the treasures hidden in an ancient pyramid, encounter ghosts in an Old West ghost town, or visit an ancient civilization on the edge of the galaxy? Developed for Texas Instruments Incorporated by Adventure International, the Adventure game series lets you e xperience these and many other adventures in the comfort of your own home. To play any of the Adventure games, you need both the Adventure Command Module (sold separately) and a cassette- or diskette based Adventure game. The module contains the general program instructions which are customized by the particular cassette tape or diskette game you use with it. Each game in the series is designed to challenge your powers of logical reasoning and may take hours, days, or even weeks to complete. However, you can leave a game and continue it at another time by saving your current adventure on a cassette tape or diskette. Copyright© 1981, Texas Instruments Incorporated. Program and database contents copyright © 1981, Adventure International and Texas Instruments Incorporated. Page l Texas Instruments ADVENTURE Description ADVENTURE Description A variety of adventure games are available on cassette tape or Pyramid of Doom diskette from your local dealer or Adventure International. To give you an idea of the exciting and interesting games you can The Pyramid of Doom adventure starts in a desert near a pool of play, a brief summary of the currently available adventures is liquid, with a pole sticking out of the sand. -

J\Dveqtute Series Tl-99/4A TI ADVENTURE MODULE (PHM 3041) and CASSETIE PLAYER OR DISK DRIVE REQUIRED SCOTT ADAMS' ADVENTURE by Scott Adams INSTRUCTIONS TEX•COMP- P.O

®~@lilt ftcdl®mID~0 j\dveqtute Series Tl-99/4A TI ADVENTURE MODULE (PHM 3041) AND CASSETIE PLAYER OR DISK DRIVE REQUIRED SCOTT ADAMS' ADVENTURE by Scott Adams INSTRUCTIONS TEX•COMP- P.o. Box 33089 • Granada Hills, CA 91344 (818) 366-6631 ADVENTURE Overview CopyrightC1981 by Adventure International, Texas Instruments, Inc. Cl 985 TEX-COMP TI Users Supply Company All rights reserved Printed with permission ADVENTURES by Scott Adams Author: Adventure International AN OVERVIEW How do you know which objects you need? Trial and er Language: TI Basic I stood at the bottom of a deep chasm. Cool air sliding ror, logic and imagination. Each time you try some action, down the sides of the crevasse hit waves of heat rising you learn a little more about the game. Hardware: TI Home Computer from a stream of bubbling lava and formed a mist over the Which brings us to the term "game" again. While called sluggish flow. Through the swrlling clouds I caught games, Adventures are actually puzzles because you have to TI Disk Drive Controller and Disk Memory Drive or glimpses of two ledges high above me: one was bricked, discover which way the pieces (actions, manipulations, use cassette tape recorder the other appeared to lead to the throne room I had been of magic words, etc.) lit together in order to gather your seeking. treasures or accomplish the mission. Like a puzzle, there are Adventure Solld State Software™ Command Module A blast of fresh air cleared the mist near my feet and a number of ways to fit the pieces together; players who like a single gravestone a broken sign appeared momen have found and stored ail the treasures (there are 13) of Ad Media: Diskette and Cassette tarily. -

Marvel Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

Marvel Pop! List PopVinyls.com Updated January 2, 2018 01 Thor 23 IM3 Iron Man 02 Loki 24 IM3 War Machine 03 Spider-man 25 IM3 Iron Patriot 03 B&W Spider-man (Fugitive) 25 Metallic IM3 Iron Patriot (HT) 03 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC ’11) 26 IM3 Deep Space Suit 03 Red/Black Spider-man (HT) 27 Phoenix (ECCC 13) 04 Iron Man 28 Logan 04 Blue Stealth Iron Man (R.I.CC 14) 29 Unmasked Deadpool (PX) 05 Wolverine 29 Unmasked XForce Deadpool (PX) 05 B&W Wolverine (Fugitive) 30 White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 Classic Brown Wolverine (Zapp) 30 GITD White Phoenix (Conquest Comics) 05 XForce Wolverine (HT) 31 Red Hulk 06 Captain America 31 Metallic Red Hulk (SDCC 13) 06 B&W Captain America (Gemini) 32 Tony Stark (SDCC 13) 06 Metallic Captain America (SDCC ’11) 33 James Rhodes (SDCC 13) 06 Unmasked Captain America (Comikaze) 34 Peter Parker (Comikaze) 06 Metallic Unmasked Capt. America (PC) 35 Dark World Thor 07 Red Skull 35 B&W Dark World Thor (Gemini) 08 The Hulk 36 Dark World Loki 09 The Thing (Blue Eyes) 36 B&W Dark World Loki (Fugitive) 09 The Thing (Black Eyes) 36 Helmeted Loki 09 B&W Thing (Gemini) 36 B&W Helmeted Loki (HT) 09 Metallic The Thing (SDCC 11) 36 Frost Giant Loki (Fugitive/SDCC 14) 10 Captain America <Avengers> 36 GITD Frost Giant Loki (FT/SDCC 14) 11 Iron Man <Avengers> 37 Dark Elf 12 Thor <Avengers> 38 Helmeted Thor (HT) 13 The Hulk <Avengers> 39 Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 14 Nick Fury <Avengers> 39 Metallic Compound Hulk (Toy Anxiety) 15 Amazing Spider-man 40 Unmasked Wolverine (Toytasktik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Gemini) 40 GITD Unmasked Wolverine (Toytastik) 15 GITD Spider-man (Japan Exc) 41 CA2 Captain America 15 Metallic Spider-man (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 B&W Captain America (BN) 16 Gold Helmet Loki (SDCC 12) 41 CA2 GITD Captain America (HT) 17 Dr. -

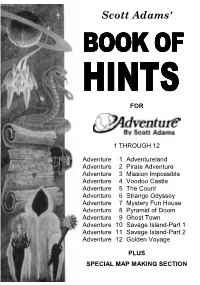

Scott Adams' BOOK of HINTS FOR

Scott Adams' BOOK OF HINTS FOR 1 THROUGH 12 Adventure 1 Adventureland Adventure 2 Pirate Adventure Adventure 3 Mission Impossible Adventure 4 Voodoo Castle Adventure 5 The Count Adventure 6 Strange Odyssey Adventure 7 Mystery Fun House Adventure 8 Pyramid of Doom Adventure 9 Ghost Town Adventure 10 Savage Island-Part 1 Adventure 11 Savage Island-Part 2 Adventure 12 Golden Voyage PLUS SPECIAL MAP MAKING SECTION THE FOLLOWING IS A METHOD USEFUL IN MAPPING ADVENTURES Each room is represented by a box with the name of the room in it, and all original items found in it noted alongside. FOREST Directions from a location are indicated by a line coming out of anywhere on the box, but with the direction leaving the box indicated by the first letter of that direction. GROVE GROVE The above shows it is East from the grove to the swamp and West from the swamp to the grove. In the case of being able to go only in one direction, an arrow is put at the end of the path. FOREST GROVE GROVE This indicates that upon leaving the grove you go north to the forest, but that you cannot return! The best way to use this system is that, upon entering a location, you draw a line representing each possible exit and its location. Later you connect them to rooms as you continue your exploration. FOREST MEADOW GROVE GROVE The advantage is that you will not forget to explore an exit once you get past your initial probe. Another advantage of this system is that you never need redraw your map as you stick extra locations anywhere on your paper. -

Acme ↓ Ti-99/4A

NEEDS Adventure-Cart ?? 12.09.2015 - Page 1 / 1 CAT1 CAT2 ACME HOUSE P/N RARI YEAR ↓ TI-99/4A - PART: by Schmitzi my CART GAME TI Adventure (Scott Adams -Adventure International) ADV PHM3041 1 : EC 1981 DISK GAME Tex-COMP Adventure Series (Adventure International) ADV ? 3 : UC 1984 DISK GAME Tex-COMP Adventure Series 13+ (12x + Knight Ironheart) (Adventure International) ADV ? 3 : UC 1984 CS1 GAME Adventure International (Scott Adams) Airline (Adventure) ADV ? 4 : RA ? DSK PROG Fritz Fritz´ Adventure Editor ADV - DL ? CS1 GAME TI Ghost Town (Adventure) ADV PHT6053 3 : UC ? CS1 GAME TI Golden Voyage (Adventure) ADV PHT? 3 : UC 1981 CS1 GAME Gilliland Ken Halls of Lost Moria (Adventure) ADV ? 3 : UC ? CS1 GAME Gilliland Ken TheDinosaurierLand (Adventure?) ADV ? 3 : UC ? DSK GAME CCK Adventure Production Last Mission (Adventure) ADV - DL ? CS1 GAME TI Mini Adventure sample (3 Adventures) ADV ? 3 : UC ? CS1 GAME TI Mission Impossible (Adventure) ADV PHT6047 3 : UC ? CS1 GAME TI Mystery Fun House (Adventure International) ADV PHT6051 3 : UC 1981 CS1 GAME TI Pirate Adventure (Adventure International) ADV PHT6043 2 : CO 1981 DISK GAME TI Pirate Adventure (Adventure International) ADV PHD5043 2 : CO 1981 CS1 GAME TI Pyramid of Doom (Adventure International) ADV PHT6052 3 : UC 1981 CART GAME TI Return to Pirate's Isle (Scott Adams - Adventure International) ADV PHM3189 2 : CO 1983 CS1 GAME TI Savage Island Series 1+2 (Adventure International) ADV PHT6054 3 : UC 1981 DISK GAME TI Savage Island Series 1+2 (Adventure International) ADV PHD6054 3 -

Download Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book PDF

Download: Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book PDF Free [843.Book] Download Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book PDF By Joe Kelly Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book you can download free book and read Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book for free here. Do you want to search free download Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book | #1059820 in Books | Marvel Comics | 2016 | Binding: Comic | Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book | |9 of 10 people found the following review helpful.| Highlights how lame Spidey has gotten since the end of Superior Spider-Man. | By badguy |Well there is 3 things about this tradeI don't like so I'll just get them out of the way immediately. 1. It starts with the 1st five issues then jumps to issue 8 which when I read the synopsis, I didn't think it would bother me because im not a fan of Deadpool or the current statu (W) Joe Kelly (A/CA) Ed McGuinness. BECAUSE YOU DEMANDED IT! The Webbed Wonder and the Merc with a Mouth are teaming up for their first ongoing series EVER! It's action, adventure and just a smattering of (b) romance in this episodic epic featuring the WORLD'S GREATEST SUPER HERO and the star of the WORLD'S GREATEST COMICS MAGAZINE. Talk about a REAL dynamic duo! Rated T+ [009.Book] Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book PDF [753.Book] Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book By Joe Kelly Epub [670.Book] Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book By Joe Kelly Ebook [478.Book] Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book By Joe Kelly Rar [871.Book] Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book By Joe Kelly Zip [837.Book] Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book By Joe Kelly Read Online Free Download: Spider-Man Deadpool #1 Comic Book pdf. -

Movies & Languages 2016-2017

Movies & Languages 2016-2017 Deadpool About the movie (subtitled version) DIRECTOR Tim Miller YEAR / COUNTRY 2016 / USA GENRE Action, Adventure, Comedy ACTORS Ryan Reynolds, Morena Baccarin, Ed Skrein, T.J. Miller, Gina Carano PLOT This film is based upon the Marvel Comics anti-hero Deadpool (Wade Wilson). Wilson is a small-time mercenary, ex-Special Forces operative. He meets Vanessa at a pub and falls in love. Life is idyllic until one day he is diagnosed with terminal cancer. Things look bleak but a man appears who says he can be cured through a treatment that gives him supernatural powers. While undergoing treatment he discovers that it will involve him becoming a mutant. The treatment results in Wilson gaining special powers but leaves him terribly disfigured. After escaping from the hospital he has two aims: find Vanessa and find the man responsible for his disfigurement. LANGUAGE Standard American English and slang. GRAMMAR Time adverbs In, on, at, no preposition: in the morning/ June/ the summer/ the third quarter/ 1998/ the sixties/ 20th century on Friday/ Friday morning/ the second of April/ the second/ Christmas Day at three fifteen/ the weekend/ the end of the week/ night/ Easter, Christmas etc./ breakfast. - We can use in for the time it takes to complete something: This production line can produce 80 vehicles in a day. - We can also use in to talk about ‘time from now’: The new offices will be ready in two months. On time or in time? On time means ‘at the right time’. In time means ‘with enough time’. -

TEXAS INSTRUMENTS HOME COMPUTER RETURN to PIRATE's ISLE Entertal NMENT Adventure #14 Return to Pirate's Isle

TEXAS INSTRUMENTS HOME COMPUTER RETURN TO PIRATE'S ISLE ENTERTAl NMENT Adventure #14 Return To Pirate's Isle Programmed by: Scott Adams Book developed and written by: Staff members of Texas Instruments Instructional Communications. Copyright© 1983 by Texas Instruments Incorporated. Solid State Cartridge program and data base contents copyright© 1983 by Scott Adams. See important warranty information at back of book. The World of Adventure The world of Adventure takes you to To help you select your next many exotic locations. In each Adventure, here is a brief summary Adventure you face unexpected of the Adventures currently danger as you carry out your available. mission. Whether your goal is to explore a mysterious pyramid or escape from a savage jungle, your reasoning power is challenged at every turn. Pirate's Adventure The Count Your adventure begins in a flat in In The Count, you wake from a nap to London, but you soon find yourself on a find yourself in a strange bed holding a strange island filled with treasure. tent stake. Now it's up to you to Explore it thoroughly and make friends discover who you are, what you are with its inhabitants, whose help you doing in Transylvania, and why the need for success. postman delivered a bottle of blood. Adventureland Strange Odyssey The Adventureland game begins in the Your Strange Odyssey begins as you forest of an enchanted world. By realize that you are stranded on a small exploring this world, you can locate 13 planetoid and must repair your ship treasures, as well as the special place before you can go home.