Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Notes on Peirce's Semiotics and Epistemology

DIAGRAMMATIC THINKING: NOTES ON PEIRCE’S SEMIOTICS AND EPISTEMOLOGY Luis Radford In this paper, I discuss the role of diagrammatic thinking within the larger context of cognitive activity as framed by Peirce’s semiotic theory of and its underpinning realistic ontology. After a short overview of Kant’s scepticism in its historical context, I examine Peirce’s attempt to rescue perception as a way to reconceptualize the Kantian “manifold of senses”. I argue that Peirce’s redemption of perception led him to a se- ries of problems that are as fundamental as those that Kant encountered. I contend that the understanding of the difficulties of Peirce’s epistemol- ogy allows us to better grasp the limits and possibilities of diagrammatic thinking. Keywords: Culture; Diagrammatic thinking; Kant; Peirce; Perception; Semiotics Pensamiento Diagramático: Notas sobre la Semiótica y la Epistemología de Peirce En este artículo se discute el papel que desempeña el concepto de pen- samiento diagramático en el contexto de la actividad cognitiva, tal y como es concebida dentro del marco de la teoría semiótica de Peirce y su subyacente ontología realista. Luego de presentar una visión general del escepticismo kantiano en su contexto histórico, se examina el esfuer- zo de Peirce por rescatar la percepción, esfuerzo que lo lleva a indagar de manera innovadora el “multiespacio de los sentidos” del que habla- ba Kant. Se mantiene que este esfuerzo lleva a Peirce a una serie de problemas que son tan fundamentales como los que Kant encontró en su propio itinerario epistemológico. Se sostiene que la comprensión de las dificultades intrínsecas a la epistemología de Peirce nos permite cernir mejor los límites y posibilidades de su pensamiento diagramático. -

Semiotics As a Cognitive Science

Elmar Holenstein Semiotics as a Cognitive Science The explanatory turn in the human sciences as well as research in "artifi- cial intelligence" have led to a little discussed revival of the classical Lockean sub-discipline of semiotics dealing with mental representations - aka "ideas" - under the heading of "cognitive science". Intelligent be- haviour is best explained by retuming to such obviously semiotic catego- ries as representation, gmbol, code, program, etc. and by investigations of the format of the mental representations. Pictorial and other "sub-linguisric" representations might be more appropriate than linguistic ones. CORRESPONDENCE: Elmar Holenstein. A-501,3-51-1 Nokendal, Kanazawa-ku Yoko- hama-shl, 236-0057, Japan. EMAIL [email protected] The intfa-semiotic cognitive tum Noam Chomsky's declaration that linguistics is a branch of psychology was understood by traditional linguists as an attack on the autonomous status of their science, a status which older structuralism endorsed by incorporating language (as a special sign system) into semiotics. Semiotics seemed to assure that genuinely linguistic relationships (grammatical and semantic relationships) were not rashly reduced to psychological or biological relationships (such as associations or adaptations). If it is looked at more closely in conjunction with the general development of the sciences in the 20th Century, the difference between Chomsky (1972: 28), who regards linguistics as a subfield of psychol- ogy, and Ferdinand de Saussure (1916: 33), for whom it is primarily a branch of "semiology", comes down to the fact that Saussure assigns linguistics in a descriptive perspective to universal semiotics, whereas Chomsky assigns it in an explanatory perspective to a special semiotics. -

!['Pragmatics and Discourse Analysis' [Review]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6904/pragmatics-and-discourse-analysis-review-176904.webp)

'Pragmatics and Discourse Analysis' [Review]

©Pragmatics and discourse analysis© [Review] Article (Accepted Version) Taylor, Charlotte (2016) 'Pragmatics and discourse analysis' [Review]. Year's Work in English Studies, 95 (1). pp. 169-178. ISSN 1471-6801 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/59463/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk 13. Pragmatics and Discourse Analysis The year 2014 proved to be an exciting one for pragmatics and discourse analysis as it was characterized by a series of cross-over initiatives, reaching out beyond the boundaries of the single fields. -

Dissertation

Dissertation A Microethnographic Discourse Analysis of the Conditions of Alienation, Engagement, Pleasure, and Jouissance from a Three-year Ethnographic Study of Middle School Language Arts Classrooms Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Craig Heggestad II, M.Ed., B.A. Graduate Program in Education: Teaching & Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. David Bloome, Advisor Dr. Caroline Clark Dr. George Newell Dr. Amy Shuman Abstract This theoretical dissertation explores the constructs of alienation, engagement, pleasure, and jouissance as they relate to research and theory on and in classroom education, in particular in middle school language arts classrooms. The research questions ask: First, how is the construct of alienation conceptualized and made manifest in the classroom and how do these empirical findings of the condition of alienation refine the theoretical construct of alienation? Second, how is the construct of engagement conceptualized and made manifest in the classroom and how do these empirical findings of the condition of engagement refine the theoretical construct of engagement? Third, how is the construct of pleasure conceptualized and made manifest in the classroom and how do these empirical findings of the condition of pleasure refine the theoretical construct of pleasure? And fourth, how is the construct of jouissance conceptualized and made manifest in the classroom and how do these empirical findings of the condition of jouissance refine the theoretical construct of jouissance? The research questions are answered through four case studies. The dissertation takes an ethnographic perspective towards research, utilizing qualitative and ethnographic methods of data collection and analysis. -

Critical Discourse Analysis of News Discourse

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Academy Publication Online ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 399-403, April 2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0804.06 Critical Discourse Analysis of News Discourse Qin Xie Shanxi Normal University, China Abstract—News discourse is one of main analysis subjects of critical discourse analysis. People can know the opinions implied by the author and grasp the real situation of the events described in the discourse by critical discourse analysis. Furthermore, it is beneficial for the audience to establish the critical awareness of News discourse and enhance the ability to critically analyze news discourse. Based on the discussion of the concept of news discourse and critical discourse analysis, the theoretical foundations and steps of critical discourse analysis, the paper illustrates the method of the critical analysis of news discourse. The author also puts forward issues that needed to pay attention to in order to improve the ability of news discourse analysis. Index Terms—news discourse, critical discourse analysis, method, emphases Critical discourse analysis can provide some guidance for the analysis of news discourse. Knowing the theoretical basis and analytical method of critical discourse analysis is beneficial to understand the actual situation of the events described in the news discourse and the implicit ideological content in news discourse. The paper explores the elements and the steps of the critical discourse analysis of news discourse. I. THE CONCEPT OF NEWS DISCOURSE AND CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS A. The Concept of News Discourse News discourse, a vital field of linguistic research, is always seen as an objective and formal linguistic form of discourse. -

A Semiotic Framework to Understand How Signs in a Collective Design Task Convey Information: a Pilot Study of Design in an Open Crowd Context

Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Administration and Research Conference Papers Administration and Research 2013 A Semiotic Framework to Understand How Signs in a Collective Design Task Convey Information: A Pilot Study of Design in an Open Crowd Context Darin Phare University of Newcastle, [email protected] Ning Gu University of Newcastle, [email protected] Anthony Williams Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Carmel Laughland University of Newcastle, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/admin_conferences Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Phare, D., Gu, N., Williams, A. P., & Laughland, C. (2013). A semiotic framework to understand how signs in a collective design task convey information: A pilot study of design in an open crowd context. In M. A. Schnabel (Ed.), Cutting edge: 47th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association. Paper presented at the Architectural Science Association, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 13-16 November (pp. 473–482). Sydney, Australia: The Architectural Science Association. This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Administration and Research at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Administration and Research Conference Papers by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M. A. Schnabel (ed.), Cutting Edge: 47th International Conference of the Architectural Science Associa- tion, pp. 473–482. © 2013, The Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA), Australia A SEMIOTIC FRAMEWORK TO UNDERSTAND HOW SIGNS IN A COLLECTIVE DESIGN TASK CONVEY INFORMATION A pilot study of design in an open crowd context DARIN PHARE, NING GU, TONY WILLIAMS and CARMEL LAUGHLAND The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia [email protected], {ning.gu, tony.williams, carmel.laughlan }@newcastlee.edu.au Abstract. -

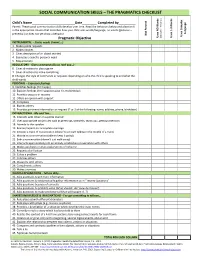

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

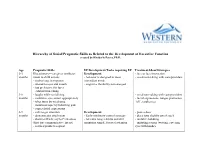

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

A Communication Aid Which Models Conversational Patterns

A communication aid which models conversational patterns. Norman Alm, Alan F. Newell & John L. Arnott. Published in: Proc. of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ‘87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. A communication aid which models conversational patterns Norman ALM*, Alan F. NEWELL and John L. ARNOTT University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, U.K. The research reported here was published in: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ’87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. The RESNA (Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America) site is at: http://www.resna.org/ Abstract: We have developed a prototype communication system that helps non-speakers to perform communication acts competently, rather than concentrating on improving the production efficiency for specific letters, words or phrases. The system, called CHAT, is based on patterns which are found in normal unconstrained dialogue. It contains information about the present conversational move, the next likely move, the person being addressed, and the mood of the interaction. The system can move automatically through a dialogue, or can offer the user a selection of conversational moves on the basis of single keystrokes. The increased communication speed which is thus offered can significantly improve both the flow of the conversation and the disabled person’s control of the dialogue. * Corresponding author: Dr. N. Alm, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, UK. A communication aid which models conversational patterns INTRODUCTION The slow rate of communication of people using communication aids is a crucial problem. -

Perspectives on Discourse Analysis: Theory and Practice

Perspectives on Discourse Analysis: Theory and Practice Perspectives on Discourse Analysis: Theory and Practice By Laura Alba-Juez Perspectives on Discourse Analysis: Theory and Practice, by Laura Alba-Juez This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2009 by Laura Alba-Juez All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0597-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0597-1 For Gustavo, Joaquín and Julian TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One................................................................................................. 5 Introducing Discourse Analysis Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 25 The Data Chapter Three............................................................................................ 45 Pragmatics Chapter Four.............................................................................................. 79 Interactional -

Critical Discourse Analysis of Martin Luther King's Speech in Socio

Advances in Language and Literary Studies Vol. 4 No. 1; January 2013 Copyright © Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Critical Discourse Analysis of Martin Luther King’s Speech in Socio-Political Perspective Muhammad Aslam Sipra Assistant Professor, Department of GRC (English), JCC, King Abdulaziz University, PO Box 80283, Jeddah 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Athar Rashid Assistant Professor, Faculty of English Language, Literature & Applied Linguistics, National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.4n.1p.27 Received: 01/12/2012 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.4n.1p.27 Accepted: 04/01/2013 Abstract The article presents the Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of the first part of King Martin Luther’s speech “When I Have a Dream” in socio-political context. The study investigates how it lies on the basis of application of Fairclough version of CDA in the first part of the text. Moreover, it explicates the terms like social, cultural and political inequalities in the light of text and framework. Keywords: CDA, Socio-political Perspective, 3D Model, Racial Discrimination, Hegemony, Dominance, Social inequalities 1. Introduction The term discourse has several definitions. In the study of language, discourse often refers to the speech patterns and usage of language, dialects, and acceptable statements, within a community. It is a subject of study of peoples who live in secluded areas and share similar speech conventions. Analysis is a process of evaluating the things by breaking them down into pieces. Discourse Analysis simply refers to the linguistic analysis of connected writing and speech.