Advanced Inorganic Chemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 13 Molecular Spectroscopy 2: Electronic Transitions

CHAPTER 13 Molecular Spectroscopy 2: Electronic Transitions I. General Features of Electronic spectroscopy. A. Visible and ultraviolet photons excite electronic state transitions. εphoton = 120 to 1200 kJ/mol. Table 13A.1 Colour, frequency, and energy of light B. Electronic transitions are accompanied by vibrational and rotational transitions of any Δν, ΔJ (complex and rich spectra in gas phase). In liquids and solids, this fine structure merges together due to collisional broadening and is washed out. Chlorophyll in solution, vibrational fine structure in gaseous SO2 UV visible spectrum. CHAPTER 13 1 C. Molecules need not have permanent dipole to undergo electronic transitions. All that is required is a redistribution of electronic and nuclear charge between the initial and final electronic state. Transition intensity ~ |µ|2 where µ is the magnitude of the transition dipole moment given by: ˆ d µ = ∫ ψfinalµψ initial τ where µˆ = −e ∑ri + e ∑Ziri € electrons nuclei r vector position of the particle i = D. Franck-Condon principle: Because nuclei are so much more massive and € sluggish than electrons, electronic transitions can happen much faster than the nuclei can respond. Electronic transitions occur vertically on energy diagram at right. (Hence the name vertical transition) Transition probability depends on vibrational wave function overlap (Franck-Condon factor). In this example: ν = 0 ν’ = 0 have small overlap ν = 0 ν’ = 2 have greatest overlap Now because the total molecular wavefunction can be approximately factored into 2 terms, electronic wavefunction and the nuclear position wavefunction (using Born-Oppenheimer approx.) the transition dipole can also be factored into 2 terms also: S µ = µelectronic i,f S d Franck Condon factor i,j i,f = ∫ ψf,vibr ψi,vibr τ = − CHAPTER 13 2 See derivation “Justification 14.2” II. -

Lecture B4 Vibrational Spectroscopy, Part 2 Quantum Mechanical SHO

Lecture B4 Vibrational Spectroscopy, Part 2 Quantum Mechanical SHO. WHEN we solve the Schrödinger equation, we always obtain two things: 1. a set of eigenstates, |ψn>. 2. a set of eigenstate energies, En QM predicts the existence of discrete, evenly spaced, vibrational energy levels for the SHO. n = 0,1,2,3... For the ground state (n=0), E = ½hν. Notes: This is called the zero point energy. Optical selection rule -- SHO can absorb or emit light with a ∆n = ±1 The IR absorption spectrum for a diatomic molecule, such as HCl: diatomic Optical selection rule 1 -- SHO can absorb or emit light with a ∆n = ±1 Optical selection rule 2 -- a change in molecular dipole moment (∆μ/∆x) must occur with the vibrational motion. (Note: μ here means dipole moment). If a more realistic Morse potential is used in the Schrödinger Equation, these energy levels get scrunched together... ΔE=hν ΔE<hν The vibrational spectroscopy of polyatomic molecules gets more interesting... For diatomic or linear molecules: 3N-5 modes For nonlinear molecules: 3N-6 modes N = number of atoms in molecule The vibrational spectroscopy of polyatomic molecules gets more interesting... Optical selection rule 1 -- SHO can absorb or emit light with a ∆n = ±1 Optical selection rule 2 -- a change in molecular dipole moment (∆μ/∆x) must occur with the vibrational motion of a mode. Consider H2O (a nonlinear molecule): 3N-6 = 3(3)-6 = 3 Optical selection rule 2 -- a change in molecular dipole moment (∆μ/∆x) must occur with the vibrational motion of a mode. Consider H2O (a nonlinear molecule): 3N-6 = 3(3)-6 = 3 All bands are observed in the IR spectrum. -

Lecture 17 Highlights

Lecture 23 Highlights The phenomenon of Rabi oscillations is very different from our everyday experience of how macroscopic objects (i.e. those made up of many atoms) absorb electromagnetic radiation. When illuminated with light (like French fries at McDonalds) objects tend to steadily absorb the light and heat up to a steady state temperature, showing no signs of oscillation with time. We did a calculation of the transition probability of an atom illuminated with a broad spectrum of light and found that the probability increased linearly with time, leading to a constant transition rate. This difference comes about because the many absorption processes at different frequencies produce a ‘smeared-out’ response that destroys the coherent Rabi oscillations and results in a classical incoherent absorption. Selection Rules All of the transition probabilities are proportional to “dipole matrix elements,” such as x jn above. These are similar to dipole moment calculations for a charge distribution in classical physics, except that they involve the charge distribution in two different states, connected by the dipole operator for the transition. In many cases these integrals are zero because of symmetries of the associated wavefunctions. This gives rise to selection rules for possible transitions under the dipole approximation (atom size much smaller than the electromagnetic wave wavelength). For example, consider the matrix element z between states of the n,l , m ; n ', l ', m ' Hydrogen atom labeled by the quantum numbers n,,l m and n',','l m : z = ψ()()r z ψ r d3 r n,l , m ; n ', l ', m ' ∫∫∫ n,,l m n',l ', m ' To make progress, first consider just the φ integral. -

Introduction to Differential Equations

Quantum Dynamics – Quick View Concepts of primary interest: The Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation Probability Density and Mixed States Selection Rules Transition Rates: The Golden Rule Sample Problem Discussions: Tools of the Trade Appendix: Classical E-M Radiation POSSIBLE ADDITIONS: After qualitative section, do the two state system, and then first and second order transitions (follow Fitzpatrick). Chain together the dipole rules to get l = 2,0,-2 and m = -2, -2, … , 2. ??Where do we get magnetic rules? Look at the canonical momentum and the Asquared term. Schrödinger, Erwin (1887-1961) Austrian physicist who invented wave mechanics in 1926. Wave mechanics was a formulation of quantum mechanics independent of Heisenberg's matrix mechanics. Like matrix mechanics, wave mechanics mathematically described the behavior of electrons and atoms. The central equation of wave mechanics is now known as the Schrödinger equation. Solutions to the equation provide probability densities and energy levels of systems. The time-dependent form of the equation describes the dynamics of quantum systems. http://scienceworld.wolfram.com/biography/Schroedinger.html © 1996-2006 Eric W. Weisstein www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Schrodinger.html Quantum Dynamics: A Qualitative Introduction Introductory quantum mechanics focuses on time-independent problems leaving Contact: [email protected] dynamics to be discussed in the second term. Energy eigenstates are characterized by probability density distributions that are time-independent (static). There are examples of time-dependent behavior that are by demonstrated by rather simple introductory problems. In the case of a particle in an infinite well with the range [ 0 < x < a], the mixed state below exhibits time-dependence. -

HJ Lipkin the Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot, Israel

WHO UNDERSTANDS THE ZWEIG-IIZUKA RULE? H.J. Lipkin The Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot, Israel Abstract: The theoretical basis of the Zweig-Iizuka Ru le is discussed with the emphasis on puzzles and paradoxes which remain open problems . Detailed analysis of ZI-violating transitions arising from successive ZI-allowed transitions shows that ideal mixing and additional degeneracies in the particle spectrum are required to enable cancellation of these higher order violations. A quantitative estimate of the observed ZI-violating f' + 2rr decay be second order transitions via the intermediate KK state agrees with experiment when only on-shell contributions are included . This suggests that ZI-violations for old particles are determined completely by on-shell contributions and cannot be used as input to estimate ZI-violation for new particle decays where no on-shell intermediate states exist . 327 INTRODUCTION - SOME BASIC QUESTIONS 1 The Zweig-Iizuka rule has entered the folklore of particle physics without any clear theoretical understanding or justification. At the present time nobody really understands it, and anyone who claims to should not be believed. Investigating the ZI rule for the old particles raises many interesting questions which may lead to a better understanding of strong interactions as well as giving additional insight into the experimentally observed suppression of new particle decays attributed to the ZI rule. This talk follows an iconoclastic approach emphasizing embarrassing questions with no simple answers which might lead to fruitful lines of investigation. Both theoretical and experimental questions were presented in the talk. However, the experimental side is covered in a recent paper2 and is not duplicated here. -

UV-Vis. Molecular Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-Vis. Molecular Absorption Spectroscopy Prof. Tarek A. Fayed UV-Vis. Electronic Spectroscopy The interaction of molecules with ultraviolet and visible light may results in absorption of photons. This results in electronic transition, involving valance electrons, from ground state to higher electronic states (called excited states). The promoted electrons are electrons of the highest molecular orbitals HOMO. Absorption of ultraviolet and visible radiation in organic molecules is restricted to certain functional groups (known as chromophores) that contain valence electrons of low excitation energy. A chromophore is a chemical entity embedded within a molecule that absorbs radiation at the same wavelength in different molecules. Examples of Chromophores are dienes, aromatics, polyenes and conjugated ketones, etc. Types of electronic transitions Electronic transitions that can take place are of three types which can be considered as; Transitions involving p-, s-, and n-electrons. Transitions involving charge-transfer electrons. Transitions involving d- and f-electrons in metal complexes. Most absorption spectroscopy of organic molecules is based on transitions of n- or -electrons to the *-excited state. These transitions fall in an experimentally convenient region of the spectrum (200 - 700 nm), and need an unsaturated group in the molecule to provide the -electrons. In vacuum UV or far UV (λ<190 nm ) In UV/VIS For formaldehyde molecule; Selection Rules of electronic transitions Electronic transitions may be allowed or forbidden transitions, as reflected by appearance of an intense or weak band according to the magnitude of εmax, and is governed by the following selection rules : 1. Spin selection rule (△S = 0 for the transition to be allowed): there should be no change in spin orientation i. -

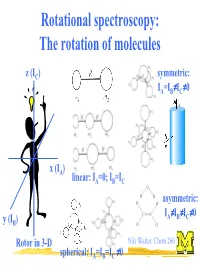

Rotational Spectroscopy: the Rotation of Molecules

Rotational spectroscopy: The rotation of molecules z (IC) symmetric: ≠ ≠ IA=IB IC 0 x (IA) linear: IA=0; IB=IC asymmetric: ≠ ≠ ≠ IA IB IC 0 y (IB) Rotor in 3-D Nils Walter: Chem 260 ≠ spherical: IA=IB=IC 0 The moment of inertia for a diatomic (linear) rigid rotor r definition: r = r1 + r2 m1 m2 C(enter of mass) r1 r2 Moment of inertia: Balancing equation: m1r1 = m2r2 2 2 I = m1r1 + m2r2 m m ⇒ I = 1 2 r 2 = µr 2 µ = reduced mass + m1 m2 Nils Walter: Chem 260 Solution of the Schrödinger equation for the rigid diatomic rotor h2 (No potential, − V 2Ψ = EΨ µ only kinetic 2 energy) ⇒ EJ = hBJ(J+1); rot. quantum number J = 0,1,2,... h B = [Hz] 4πI ⇒ EJ+1 -EJ = 2hB(J+1) Nils Walter: Chem 260 Selection rules for the diatomic rotor: 1. Gross selection rule Light is a transversal electromagnetic wave a polar rotor appears to have an oscillating ⇒ a molecule must be polar to electric dipole Nils Walter: Chem 260 be able to interact with light Selection rules for the diatomic rotor: 2. Specific selection rule rotational quantum number J = 0,1,2,… describes the angular momentum of a molecule (just like electronic orbital quantum number l=0,1,2,...) and light behaves as a particle: photons have a spin of 1, i.e., an angular momentum of one unit and the total angular momentum upon absorption or emission of a photon has to be preserved ⇒⇒∆∆J = ± 1 Nils Walter: Chem 260 Okay, I know you are dying for it: Schrödinger also can explain the ∆J = ± 1 selection rule Transition dipole µ = Ψ µΨ dτ moment fi ∫ f i initial state final state ⇒ only if this integral -

Shaping Polaritons to Reshape Selection Rules

Shaping Polaritons to Reshape Selection Rules 1,2 2 3 2 2,4 Francisco Machado∗ , Nicholas Rivera∗ , Hrvoje Buljan , Marin Soljaˇci´c , Ido Kaminer 1Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 97420, USA 2Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 3Department of Physics, University of Zagreb, Zagreb 10000, Croatia. 4Department of Electrical Engineering, Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel. The discovery of orbital angular momentum (OAM) in light established a new degree of freedom by which to control not only its flow but also its interaction with matter. Here, we show that by shaping extremely sub-wavelength polariton modes, for example by imbuing plasmon and phonon polariton with OAM, we engineer which transitions are allowed or forbidden in electronic systems such as atoms, molecules, and artificial atoms. Crucial to the feasibility of these engineered selection rules is the access to conventionally forbidden transitions afforded by sub-wavelength polaritons. We also find that the position of the absorbing atom provides a surprisingly rich parameter for controlling which absorption processes dominate over others. Additional tunability can be achieved by altering the polaritonic properties of the substrate, for example by tuning the carrier density in graphene, potentially enabling electronic control over selection rules. Our findings are best suited to OAM-carrying polaritonic modes that can be created in graphene, monolayer conductors, thin metallic films, and thin films of polar dielectrics such as boron nitride. By building on these findings we foresee the complete engineering of spectroscopic selection rules through the many degrees of freedom in the shape of optical fields. -

Laporte Selection Rule (Only for Systems with Inversion Symmetry)

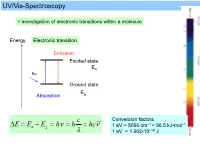

UV/Vis-Spectroscopy = investigation of electronic transitions within a molecule Energy Electronic transition Emission Excited state Ea hn Ground state E Absorption g c Conversion factors ~ –1 –1 E Ea Eg hn h hcn 1 eV = 8066 cm = 96.5 kJ•mol 1 eV = 1.602•10–19 J n+ UV/Vis spectra of the [M(H2O)6] cations general observation: d1, d4, d6, d9 (one band) d2, d3, d7, d8 (three bands) d5 (several sharp, relatively weak bands) (only high-spin compounds) d0, d10: no absorption bands Intensities of absorption bands –1 –1 emax (extinction coefficient), dimension M cm SiO2 cuvette Lambert-Beer law: emax = E / (c·l) 5 –1 –1 range: emax = 0 to > 10 M cm l = diameter e of cuvette emax 1 n n~ c 400 nm = 25000 cm-1 200 nm = 50000 cm-1 max Selection rules* spin multiplicity MS = 2S+1 S = Ss = n/2 (total spin quantum 1. Spin selection rule S = 0 or MS = 0 number) (Transition between same spin states allowed: singlet -> singlet, triplet -> triplet, others are forbidden: singlet -> triplet, doublet -> singlet, etc.) 2+ [Mn(H2O)6] Pauli-Principle not obeyed hn S = 5/2 S = 5/2 S = 3/2 S = 1, forbidden e < 1 M‒1cm‒1 .. only one electron is involved in any transition max * were developed for metal atoms and ions (where they are rigorously obeyed), not complexes Spin selection rule 2+ [Co(H2O)6] 3+ Pauli Prinziple [Cr(NH3)6] obeyed hn S = 3/2 S = 3/2 S = 0, allowed ‒1 ‒1 emax = 1-10 M cm In the case of spin orbit coupling (as is the case for trans.-metal complexes), the spin-selection rule is partially lifted (=> weak, so-called inter-combination bands arise with e = 0.01 – 1.0 M‒1cm‒1) 4 2 III III II (example: A2g→ Eg- transition, in the case of Cr , l.s.-Co , or Mn ) an e ~ 0.01 M‒1cm‒1 is hardly detectable Orbital selection rule L = 1 2. -

CHAPTER 12 Molecular Spectroscopy 1: Rotational and Vibrational Spectra

CHAPTER 12 Molecular Spectroscopy 1: Rotational and Vibrational Spectra I. General Features of Spectroscopy. A. Overview. 1. Bohr frequency rule: hc Ephoton = hν = = hcν˜ = Eupper −Elower λ 1 Also remember ν˜ = (usually in cm-1) λ € 2. Types of spectroscopy (three broad types): -emission € -absorption -scattering Rayleigh Stokes Anti-Stokes CHAPTER 12 1 3. The electromagnetic spectrum: Region λ Processes gamma <10 pm nuclear state changes x-ray 10 pm – 10 nm inner shell e- transition UV 10 nm – 400 nm electronic trans in valence shell VIS 400 – 750 nm electronic trans in valence shell IR 750 nm – 1 mm Vibrational state changes microwave 1 mm – 10 cm Rotational state changes radio 10 cm – 10 km NMR - spin state changes 4. Classical picture of light absorption – since light is oscillating electric and magnetic field, interaction with matter depends on interaction with fluctuating dipole moments, either permanent or temporary. Discuss vibrational, rotational, electronic 5. Quantum picture: Einstein identified three contributions to transitions between states: a. stimulated absorption b. stimulated emission c. spontaneous emission Stimulated absorption transition probability w is proportional to the energy density ρ of radiation through a proportionality constant B w=B ρ The total rate of absorption W depends on how many molecules N in the light path, so: W = w N = N B ρ CHAPTER 12 2 Now what is B? Consider plane-polarized light (along z-axis), can cause transition if the Q.M. transition dipole moment is non-zero. µ = ψ *µˆ ψdτ ij ∫ j z i Where µˆ z = z-component of electric dipole operator of atom or molecule Example: H-atom € € - e r + µˆ z = −er Coefficient of absorption B (intrinsic ability to absorb light) 2 µij B = 6ε 2€ Einstein B-coefficient of stimulated absorption o if 0, transition i j is allowed µ ij ≠ → µ = 0 forbidden € ij € 6. -

Wls-76/42-Ph

WlS-76/42-Ph A KlfO UNDERSTANDS THE IhCIG-IIZUKA RULE? H.J. Lipkin The Kctzsann Institute of Science Rchovot, Israel Abstract: The theoretical basis of the Zweig-Iizuka Rule is discussed *ith the emphasis on puzzles and . paradoxes which remain open problems. Detailed analysis of Zl-violating transitions arising from successive Zl-allowcd transitions shows that ideal mixing and additional degeneracies in the particle spectrum are required to enable cancellation of these higher order violations. A quantitative estimate of the observed Zl-violating f •* 2ff decay be second order transitions via the intermediate KK state agrees with experiment when only on-shell contributions are included. This suggests that Zl-violations for old particles are determined completely by on-shell contributions and cannot be used as input to estimate Zl-violation for new particle decays where no on-shell intermediate states exist. t INTRODUCTION - SOMli BASIC QULSHONS The Zwcig-Iituka rule has entered the folklore of particle physics without any clear theoretical understanding or justification. At the present time nobody really understands it, and anyone who clliis to should not be believed. Investigating the ZI rule for the old particles raises many interesting questions which say lead to a better understanding of strong interactions as well as giving additional insight into the experiocntally observed suppression of new particle decays attributed to the ZI rule. This talk follows an iconoclastic approach emphasizing embarrassing questions with no simple answers which Bight lead to fruitful lines of investigation. Both theoretical and experimental questions were presented in the talk. However, 2 the experimental side is covered in a recent paper and is not duplicated here. -

Diatomic Vibrational Spectra

Diatomic vibrational spectra Molecular vibrations Typical potential energy curve of a diatomic molecule: Parabolic approximation close to Re: 1 V kx2 x R R 2 e k = force constant of the bond. The steeper the walls of the potential, the stiffer the bond, the greater the force constant. Connection between the shape of molecular potential energy curve and k: we expand V(x) around R = Re by a Taylor series: 2 2 dV 1 d V 2 1 d V 2 Vx V0 x x ... x dx 2 2 2 2 0 dx 0 dx 0 V(0) = constant set arbitrarily to zero. first derivative of V is 0 at the minimum. for small displacements we ignore all high terms. Hence, the first approximation to a molecular potential energy curve is a parabolic potential with: d2V k 2 dx 0 if V(x) is sharply curved, k is large. if V(x) is wide and shallow, k is small. Schrödinger equation for the relative motion of two atoms of masses m1 and m2 with a parabolic potential energy: 2 d2 1 kx2 E 2 2meff dx 2 m1m2 where meff = effective (or reduced) mass: meff m1 m2 Use of meff to consider the problem from the perspective of the motion of molecule as a whole. Example: homonuclear diatomic m1 = m2 = m: meff m / 2. XH, where mX >> mH: meff mH. Same Schrödinger equation as for the particle of mass m undergoing harmonic motion. Therefore, the permitted vibrational energy levels are: 1 k En n with: and: n = 0, 1, 2, … 2 meff The vibrational wavefunctions are the same as those discussed for the harmonic oscillator.