Bird Observer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lotic Volunteer Temperature, Electrical Conductivity, and Stage Sensing Network

NOVEMBER 2012, NO 1 The Lotic Volunteer Temperature, Electrical Conductivity, and Stage Sensing Network A LoVoTECS Newsletter by Mark Green Welcome to our newsletter! This is the first in what will become quarterly updates about the happen- ings in our Lotic Volunteer Temperature, Elec- trical Conductivity, and Stage Sensing network (LoVoTECS). We will use this forum to update our partners on activities within the network and provide statewide syntheses of the the data you are collecting. But first, a little bit about who we are. LoVoTECS is funded by the National Sci- ence Foundation through a cooperative agreement to the New Hampshire Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) pro- gram. The network is being coordinated by a group of researchers, staff, and students at Plymouth State University – and implemented by our broad group of partners, including educa- tors, researchers, government agencies, non-profit organizations, and citizen scientists. Our goal is to improve our understanding of New Hampshire’s water resources and help develop a technically advanced workforce by providing educational opportunities to in- teract with large data sets. We will accomplish this by building a state-of-the-art, broad scale and high-frequency hydrologic sensing network using simple sensors operated by a diverse group of partners. We are grateful for your collaboration and are excited to improve hydrologic knowledge and scientific training in New Hampshire. Mark is an Assistant Professor of Hydrology at Plymouth State University’s Center for the Environment. September K-12 Teacher Workshop of data, and an overview of the research scope of the by Doug Earick LoVoTECS project. -

Summer 2004 Vol. 23 No. 2

Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Summer 2004 Vol. 23, No. 2 Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page ii New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 23, Number 2 Summer 2004 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309 [email protected] Text Editor: Dorothy Fitch Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; William Taffe, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Production Assistants: Kathie Palfy, Diane Parsons Assistants: Marie Anne, Jeannine Ayer, Julie Chapin, Margot Johnson, Janet Lathrop, Susan MacLeod, Dot Soule, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano, Robert Vernon Volunteer Opportunities and Birding Research: Susan Story Galt Photo Quiz: David Donsker Where to Bird Feature Coordinator: William Taffe Maps: William Taffe Cover Photo: Juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owl, by Paul Knight, June, 2004, Francestown, NH. Paul watched as it flew up with a mole in its talons. New Hampshire Bird Records (NHBR) is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon (NHA). Bird sightings are submitted to NHA and are edited for publication. A computerized print- out of all sightings in a season is available for a fee. To order a printout, purchase back issues, or volunteer your observations for NHBR, please contact the Managing Editor at 224-9909. Published by New Hampshire Audubon New Hampshire Bird Records © NHA April, 2005 Printed on Recycled Paper Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page 1 Table of Contents In This Issue Volunteer Request . .2 A Checklist of the Birds of New Hampshire—Revised! . -

DRAFT June 18, 2003, 2003 of STATE/LYME AGREED-TO VERSION

Return to: Office of the Attorney General Civil Bureau 33 Capitol Street Concord, New Hampshire 03301-6397 GRANT OF CONSERVATION EASEMENT KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS, that THE TRUST FOR PUBLIC LAND d/b/a TPL-NEW HAMPSHIRE, a California public benefit corporation with a place of business at 54 Portsmouth Street, Concord, New Hampshire 03301 (the “Fee Owner” which word shall, unless the context clearly indicates otherwise, include the Fee Owner’s legal representatives, successors and assigns), hereby grants to the STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, acting by and through the Department of Resources and Economic Development with an address of 172 Pembroke Road, P.O. Box 1856, Concord, New Hampshire 03302-1856 (the “Easement Holder” which word shall, unless the context clearly indicates otherwise, include the Easement Holder's legal representatives, successors and assigns), with quitclaim covenants, in perpetuity, the Conservation Easement (the “Easement”) hereinafter described with respect to that certain parcel of land (the “Property”), being primarily unimproved land and one hundred seasonal recreational camps, situated in the Towns of Pittsburg, Clarksville and Stewartstown, Coos County, State of New Hampshire, more particularly described in Exhibit A attached hereto and made a part hereof, subject to the matters set forth on Exhibit B attached hereto and made a part hereof. The underlying fee interest in the Property will be held and conveyed subject and subordinate to this Easement. PREAMBLE The Property is located in the Northern Forest, a 26 million acre area stretching from Maine through New Hampshire and Vermont across northern New York almost to Lake Ontario that is the subject of the Congressionally funded report entitled “Finding Common Ground: Conserving the Northern Forest” (September, 1994) prepared by the Northern Forest Lands Council and as such has strong regional and multi-state significance. -

New Hampshire River Protection and Energy Development Project Final

..... ~ • ••. "'-" .... - , ... =-· : ·: .• .,,./.. ,.• •.... · .. ~=·: ·~ ·:·r:. · · :_ J · :- .. · .... - • N:·E·. ·w··. .· H: ·AM·.-·. "p• . ·s;. ~:H·1· ··RE.;·.· . ·,;<::)::_) •, ·~•.'.'."'~._;...... · ..., ' ...· . , ·....... ' · .. , -. ' .., .- .. ·.~ ···•: ':.,.." ·~,.· 1:·:,//:,:: ,::, ·: :;,:. .:. /~-':. ·,_. •-': }·; >: .. :. ' ::,· ;(:·:· '5: ,:: ·>"·.:'. :- .·.. :.. ·.·.···.•. '.1.. ·.•·.·. ·.··.:.:._.._ ·..:· _, .... · -RIVER~-PR.OT-E,CT.10-N--AND . ·,,:·_.. ·•.,·• -~-.-.. :. ·. .. :: :·: .. _.. .· ·<··~-,: :-:··•:;·: ::··· ._ _;· , . ·ENER(3Y~EVELOP~.ENT.PROJ~~T. 1 .. .. .. .. i 1·· . ·. _:_. ~- FINAL REPORT··. .. : .. \j . :.> ·;' .'·' ··.·.· ·/··,. /-. '.'_\:: ..:· ..:"i•;. ·.. :-·: :···0:. ·;, - ·:··•,. ·/\·· :" ::;:·.-:'. J .. ;, . · · .. · · . ·: . Prepared by ~ . · . .-~- '·· )/i<·.(:'. '.·}, •.. --··.<. :{ .--. :o_:··.:"' .\.• .-:;: ,· :;:· ·_.:; ·< ·.<. (i'·. ;.: \ i:) ·::' .::··::i.:•.>\ I ··· ·. ··: · ..:_ · · New England ·Rtvers Center · ·. ··· r "., .f.·. ~ ..... .. ' . ~ "' .. ,:·1· ,; : ._.i ..... ... ; . .. ~- .. ·· .. -,• ~- • . .. r·· . , . : . L L 'I L t. ': ... r ........ ·.· . ---- - ,, ·· ·.·NE New England Rivers Center · !RC 3Jo,Shet ·Boston.Massachusetts 02108 - 117. 742-4134 NEW HAMPSHIRE RIVER PRO'l'ECTION J\ND ENERGY !)EVELOPMENT PBOJECT . -· . .. .. .. .. ., ,· . ' ··- .. ... : . •• ••• \ ·* ... ' ,· FINAL. REPORT February 22, 1983 New·England.Rivers Center Staff: 'l'bomas B. Arnold Drew o·. Parkin f . ..... - - . • I -1- . TABLE OF CONTENTS. ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS . ~ . • • . .. • .ii EXECUTIVE -

Stream Crossings Like Habitat Connectivity, Streams Require Continuity to Support the Movement of Aquatic Organisms

MANAGING STATE LANDS FOR WILDLIFE Stream Crossings Like habitat connectivity, streams require continuity to support the movement of aquatic organisms. Many species need different habitats for feeding, breeding, and shelter. The ability to move up or down stream is required for the natural dispersal of individuals. Disruption of stream continuity can result in the loss and degradation of habitat, block wildlife movement, and disrupt the ecological processes that occur in streams over time. Intersections of streams and roads—or stream crossings—have been historically designed to pass water under a road without consideration of stream continuity. Flow variability, natural sediment transport, and aquatic organism passage are overlooked. Characteristic problems of culverts include undersized, shallow, or perched crossings resulting in low or high flow, unnatural bed materials, scouring, erosion, clogging, and ponding. Bridges generally have a lesser impact on streams but, if improperly designed, can still result in sediment deposition and/or streambed degradation. Good stream crossing for wildlife are also good for people. Proper design and placement reduce erosion and damage to roads, infrastructure, and personal property. Click here for more information on Fish and Game’s Fish Habitat Program. Click here for New Hampshire’s Stream Crossing Guidelines and related resources from New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services. Mascoma WMA (Canaan) This property contained a 15 foot culvert used to cross the 60-80 foot wide Mascoma River that bisects the property. The culvert was installed by the former landowner. The constriction caused by the culvert led to significant riverbank erosion both up and downstream, forced the river to change course, and deterred fish passage. -

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed Alphabetically by Last Name Of

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed alphabetically by last name of presenting author AOS 2019 Meeting 24-28 June 2019 ORAL PRESENTATIONS Variability in the Use of Acoustic Space Between propensity, renesting intervals, and renest reproductive Two Tropical Forest Bird Communities success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) by fol- lowing 1,922 nests and 1,785 unique breeding adults Patrick J Hart, Kristina L Paxton, Grace Tredinnick from 2014 2016 in North and South Dakota, USA. The apparent renesting rate was 20%. Renesting propen- When acoustic signals sent from individuals overlap sity declined if reproductive attempts failed during the in frequency or time, acoustic interference and signal brood-rearing stage, nests were depredated, reproduc- masking occurs, which may reduce the receiver’s abil- tive failure occurred later in the breeding season, or ity to discriminate information from the signal. Under individuals had previously renested that year. Addi- the acoustic niche hypothesis (ANH), acoustic space is tionally, plovers were less likely to renest on reservoirs a resource that organisms may compete for, and sig- compared to other habitats. Renesting intervals de- naling behavior has evolved to minimize overlap with clined when individuals had not already renested, were heterospecific calling individuals. Because tropical after second-year adults without prior breeding experi- wet forests have such high bird species diversity and ence, and moved short distances between nest attempts. abundance, and thus high potential for competition for Renesting intervals also decreased if the attempt failed acoustic niche space, they are good places to examine later in the season. Lastly, overall reproductive success the way acoustic space is partitioned. -

COMPARING HUMANS and BIRDS by Daniel C. Mann a Dissertation

STABILIZING FORCES IN ACOUSTIC CULTURAL EVOLUTION: COMPARING HUMANS AND BIRDS by Daniel C. Mann A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 2019 DANIEL C. MANN All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JULIETTE BLEVINS Date Chair of the Examining Committee GITA MARTOHARDJONO Date Executive Officer MARISA HOESCHELE DAVID C. LAHTI MICHAEL I. MANDEL Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract STABILIZING FORCES IN ACOUSTIC CULTURAL EVOLUTION: COMPARING HUMANS AND BIRDS By Daniel C. Mann Advisor: Professor Juliette Blevins Learned acoustic communication systems, like birdsong and spoken human language, can be described from two seemingly contradictory perspectives. On one hand, learned acoustic communication systems can be remarkably consistent. Substantive and descriptive generalizations can be made which hold for a majority of populations within a species. On the other hand, learned acoustic communication systems are often highly variable. The degree of variation is often so great that few, if any, substantive generalizations hold for all populations in a species. Within my dissertation, I explore the interplay of variation and uniformity in three vocal learning species: budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus), house finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), and humans (Homo sapiens). Budgerigars are well-known for their versatile mimicry skills, house finch song organization is uniform across populations, and human language has been described as the prime example of variability by some while others see only subtle variations of largely uniform system. -

Bush Shrikes to Old World Sparrows

15_123(3)BookReviews.qxd:CFN_123(3) 1/26/11 11:42 AM Page 271 2009 BOOK REVIEWS 271 Handbook of Birds of the World. Volume 14: Bush Shrikes to Old World Sparrows Edited by Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott, and David Christie. Lynx Edicions, Montseny, 8, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain. 896 pages, 335 CAD Cloth. I normally jump to the species plates and descrip- I think, as they have shown these birds sitting on a tions, but this time I stopped at the foreword . This branch [a logical choice] and have foregone the magic essay on birding is dedicated to Max Nicholson, the of their display. There are wonderful photographs of man who took us from bird collecting to bird watching. birds in display, but you really need to be there or at Nicholson was also instrumental in the creation and least watch a video to see these spectacles in their growth of many initiatives like the British Trust for true, shimmering glory. There are about 80 photos of Ornithology, the World Wildlife Fund, and the Royal birds-of-paradise, 40% of which were contributed by Society for the Protection of Birds. The essay “Bird- two men, Tim Lehman and Brian Coates. These photos ing Past, Present and Future: a Global View ” by show almost 90% of the species . Stephen Moss is an overview history of birdwatching The second family is the crows. These birds are from the pre-binocular era to the present. It gives a easier to depict , as many are black, sometimes with fascinating look at our cherished hobby [or is that reli- white or grey, although the jays can be remarkably col- gion?] using a broad frame of reference. -

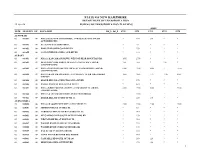

STATE of NEW HAMPSHIRE DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION 19-Apr-04 BUREAU of TRANSPORTATION PLANNING AADT TYPE STATION FC LOCATION Int 1 Int 2 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 19-Apr-04 BUREAU OF TRANSPORTATION PLANNING AADT TYPE STATION FC LOCATION Int_1 Int_2 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 ACWORTH 82 001051 08 NH 123A EAST OF COLD RIVER (.75 MILES EAST OF SOUTH * 390 280 * * ACWORTH CTR) 82 001052 08 ALLEN RD AT LEMPSTER TL * 70 * * * 82 001053 09 FOREST RD OVER COLD RIVER * 190 * * * 82 001055 08 COLD RIVER RD OVER COLD RIVER * 110 * * * ALBANY 82 003051 07 NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) WEST OF BEAR MOUNTAIN RD 1500 2700 * * * 82 003052 07 BEAR NOTCH RD NORTH OF KANCAMAGUS HWY (SB/NB) 700 750 * 970 * (81003045-003046) 62 003053 02 NH 16 (CONTOOCOOK MTN HWY) AT TAMWORTH TL (SB/NB) 6200 7200 6600 * 7500 (61003047-003048) 02 003054 07 NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) AT CONWAY TL (EB-WB)(01003062- 1956 1685 1791 1715 2063 01003063) 82 003055 09 DRAKE HILL RD OVER CHOCORUA RIVER * 270 * * * 82 003056 08 PASSACONAWAY RD EAST OF NH 112 * 420 * * * 82 003058 02 NH 16 (WHITE MOUNTAIN HWY) AT MADISON TL (SB/NB) 8200 7500 6800 * 9300 (81003049-003050) 82 003060 07 NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) OVER TWIN BROOK * 2200 * * * 82 003061 09 DRAKE HILL RD SOUTH OF NH 16 * 120 140 * * ALEXANDRIA 22 005050 06 NH 104 (RAGGED MTN HWY) AT DANBURY TL 2300 2300 2100 * 2500 82 005051 09 SMITH RIVER RD AT HILL TL * 50 * * * 82 005052 08 CARDIGAN MOUNTAIN RD AT BRISTOL TL * 940 * * * 82 005053 09 MT CARDIGAN RD SOUTH OF WADHAMS RD * 130 * * * 82 005056 08 WEST SHORE RD AT BRISTOL TL * 720 * * * 82 005057 09 WASHBURN RD OVER PATTEN BROOK * 220 * * * 82 005058 08 WASHBURN RD OVER PATTEN BROOK * 430 * * * 82 -

New Hampshire!

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department NEW HAMPSHIRE FRESHWATER FISHING 2021 DIGEST Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2021 Go Fish New Hampshire! Nearly 1,000 fishable lakes and 12,000 miles of rivers and streams… The Official New Hampshire fishnh.com Digest of Regulations Why Smoker Craft? It takes a true fisherman to know what makes a better fishing experience. That’s why we’re constantly taking things to the next level with design, engineering and construction that deliver best-in-class aluminum fishing boats for every budget. \\Pro Angler: \\Voyager: Grab Your Friends and Head for the Water Years of Worry-Free Reliability More boat for your bucks. The Smoker Craft Pro Angler The Voyager is perfect for the no-nonsense angler. aluminum fishing boat series leads the way with This spacious and deep boat is perfect for the first feature-packed value. time boat buyer or a seasoned veteran who is looking for a solid utility boat. Laconia Alton Bay Hudson 958 Union Ave., PO Box 6145, 396 Main Street 261 Derry Road Route 102 Laconia, NH 03246 Alton Bay, NH 03810 Hudson, NH 03051 603-524-6661 603-875-8848 603-595-7995 www.irwinmarine.com Jan. 1–Dec. 31, 2021 NEW HAMPSHIRE Fish and Game Department FRESHWATER FISHING 2021 DIGEST Lakes and Rivers Galore I am new to Fish and Game, but I was born and raised in New Hampshire and have spent a lifetime working in the outdoors of our Granite State. I grew up with my friends ice fishing for lake trout and cusk on the hard waters of Lake Winnipesaukee and Lake Winnisquam with my father and his friends. -

Public Access and Recreation & Road Management Plans

Connecticut Lakes Headwaters Working Forest Recreation Program Public Access and Recreation & Road Management Plans -Volume 1- For the property owned by the Connecticut Lakes Timber Company and State of New Hampshire Department of Resources and Economic Development Initial Plan Issued: July 3, 2007 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................................2 1.1. What are the purpose and scope of the plan? .....................................................................2 1.2. What is the Connecticut Lakes Headwaters Working Forest Recreation Program and how was it created? ............................................................................................................3 1.3. How is the Initial Plan different from the Interim Plan? ....................................................6 1.4. What substantive requirements must the Plans meet?........................................................6 1.5. What was the planning process?.........................................................................................7 1.5.1. Organizational Meetings ................................................................................................7 1.5.2. Visioning Sessions .........................................................................................................8 1.5.3. Issues and Management Alternatives.............................................................................9 1.6. How did the public influence -

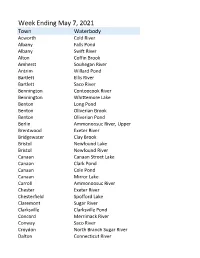

Week Ending May 7, 2021

Week Ending May 7, 2021 Town Waterbody Acworth Cold River Albany Falls Pond Albany Swift River Alton Coffin Brook Amherst Souhegan River Antrim Willard Pond Bartlett Ellis River Bartlett Saco River Bennington Contoocook River Bennington Whittemore Lake Benton Long Pond Benton Oliverian Brook Benton Oliverian Pond Berlin Ammonoosuc River, Upper Brentwood Exeter River Bridgewater Clay Brook Bristol Newfound Lake Bristol Newfound River Canaan Canaan Street Lake Canaan Clark Pond Canaan Cole Pond Canaan Mirror Lake Carroll Ammonoosuc River Chester Exeter River Chesterfield Spofford Lake Claremont Sugar River Clarksville Clarksville Pond Concord Merrimack River Conway Saco River Croydon North Branch Sugar River Dalton Connecticut River Week Ending May 7, 2021 Town Waterbody Dalton Moore Reservoir Deerfield Hartford Brook Deerfield Lamprey River Dover Cocheco River Dublin Stanley Brook Durham Lamprey River Enfield Crystal Lake Enfield Mascoma Lake Errol Akers Pond Exeter Exeter Reservoir Exeter Exeter River Farmington Cocheco River Farmington Ela River Farmington Mad River Franklin Webster Lake Freedom Ossipee Lake Fremont Exeter River Gilford Winnipesaukee Lake Gilmanton Kids Pond Gilmanton Nighthawk Hollow Brook Gilmanton Suncook River Gorham Peabody River Grafton Tewksbury Pond Greenland Winnicut River Hancock Moose Brook Harrisville Nubanusit Brook Harrisville Silver Lake Haverhill Oliverian Brook Henniker French Pond Hillsborough Contoocook River Hillsborough Gould Pond Week Ending May 7, 2021 Town Waterbody Jackson Ellis River Jaffrey