Arxiv:1609.07486V1 [Cond-Mat.Mtrl-Sci] 23 Sep 2016 Tal Material of Ref

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dimerization of CO2 at High Pressure and Temperature

Dimerization of CO2 at High Pressure and Temperature Francesco Tassone,[a] Guido L. Chiarotti,[a] Roger Rousseau,[a] Sandro Scandolo,[b, c] and Erio Tosatti*[a, b, c] Dedicated to Professor Michele Parrinello on the occasion of his 60th birthday. Understanding the behavior of simple molecular systems under the combined effect of high pressure (P) and tempera- ture (T) has important implications in the modeling of planeta- ry interiors, in the chemistry of detonation, and in the synthe- sis of new materials. Extreme conditions of P and T can be par- tially accessed in the laboratory either in heated diamond-anvil cells or in shock wave experiments, where dramatic changes in the chemical and physical properties of simple molecules have been reported.[1] Depending on the detailed situation, com- pression may result in the formation of intermolecular bonds, or in disproportionation, or even in full dissociation into the constituent elements. In such a context, the theoretical predic- tion of stable or metastable structures and of their properties is highly desirable. However, this requires an accurate quantum description, capable of discriminating the often subtle changes in the nature of chemical bonds. First-principles molecular dy- namics methods with variable-cell, constant-pressure dynam- ics[2]—a natural derivation of the two revolutionary methods introduced more than 20 years ago by Michele Parrinello to- gether with Roberto Car[3] and Anees Rahman[4]—offer a unique tool for this kind of exploration. [5] Molecular CO2 was independently observed and predict- ed[6] to transform into extended quartz-like covalent solids at moderately high pressures (about 50 GPa). -

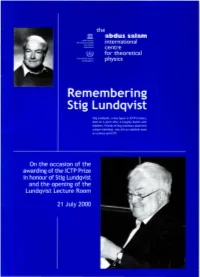

Remembering Stig Lundqvist

Remembering Stig Lundqvist Scientist Friend Among his many attributes, Stig Lundqvist was an Stig was a devoted friend and colleague, and a autstanding scientist . He conducted fundamental warm human being with a wide range of interests and studies of electron gas, particularly the role of many talents : He was a jazz musician with a deep collective plasmon excitations in spectroscopic appreciation of classical music - he played the properties. One particularly important study of trumpet and arranged music for a jazz group as an Stig's concentrated on particle spectroscopy. He undergraduate; he was a creative chef specializing found that a resonance occurs when the spectrum is in fish dishes but, as he often remarked, second in probed at an energy corresponding to the plasmeron culinary talent to his sister Kersti; he was a superb energy . The plasmeron is a bound state of a hole and theoretical condensed matter physicist well-versed a plasmon. These excitations were observed in other areas of physics, making him a particularly experimentally and provide a fundamental aspect of effective member and chairman of the Nobel Prize electron gas . Another important aspect of his work Committee in Physics; and he was a creative organiser concerned the electron tunnelling spectrum in metals. of international conferences, symposia and advanced He studied the single quasi particle and collective summer schools, enabling him to spark interactions mode spectrum of solids, again probing fundamental among physicists worldwide . In 1990, when Stig reached aspects of correlations in the electronic properties the age of 65, after a long and distinguished career of metal and superconductars. -

Erio TOSATTI Dati Personali

Erio TOSATTI Dati personali ________________________________________________________________ Nascita: 9 Novembre 1943, Nonantola (Modena) Nazionalita’: Italiana Stato civile: sposato, 3 figli Indirizzo: SISSA, via Bonomea 265, I-34136 Trieste; casa, Viale Miramare 41, I-34135 Trieste, Italy. Telefoni: +39-348-8606809 (cell); +39-040-43727 (casa) +39-040-3787-438 (SISSA); -437 segreteria; -528 fax E-mail : [email protected] Web: http://sites.google.com/site/tosattierio/ Studi ________________________________________________________________ 1967 Laurea in Fisica, Universita’ di Modena, cum Laude 1970 Perfezionamento in Fisica Teorica, Scuola Normale Superiore Pisa, magna cum Laude. Posizioni _______________________________________________________________ 1980-2014 Professore ordinario di Struttura della Materia, SISSA area Fisica Fondatore del Settore di Teoria degli Stati Condensati, SISSA 1977-2014 Co-fondatore e membro senior, Condensed Matter Group, International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) Trieste 2002-03 Direttore a.i,, ICTP, Trieste 2003-2014 Presidente, Ufficio Programmi Scientifici, ICTP 1970-71 Sottotenente GARF (compl.), Servizio Meteorologico, Aeronautica Militare Italiana 1971-76 Riceratore CNR, Istituto di Fisica “G. Marconi” Universita’ di Roma 1972-73 Royal Society/NATO Fellow, Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, GB 1974 DFG Stipendium, Universita’ di Stoccarda, Germania Ovest. 1977 Senior NATO Fellow, Universita’ di Stanford, USA 1977-80 Ricercatore Capo CNR, e Professore Incaricato di Fisica dei Solidi, Istituto -

INTRODUCTION SPEECH DIRAC MEDAL in HONOUR of ROBERTO CAR and MICHELE PARRINELLO

2145-6 Spring College on Computational Nanoscience 17 - 28 May 2010 INTRODUCTION SPEECH DIRAC MEDAL IN HONOUR OF ROBERTO CAR and MICHELE PARRINELLO Erio TOSATTI SISSA Trieste Italy circa 1980 “molecular dynamics” computer simulations Berni of condensed matter: solids, liquids, etc Alder Aneesur Rahman “density functional” electronic structure and Walter total energy calculations of solids, etc Kohn Lu Sham Marvin Cohen FRANCO BASSANI 1929-2008 ROBERTO CAR ROBERTO ALFONSO CAR BALDERESCHI Modena 18 Oct 1981 ROBERTO ANNABELLA… …HELPED YANKING BOTH OF THEM AWAY FROM IBM….. ….TO TRIESTE! MICHELE PARRINELLO 1970s: MICHELE PARRINELLO IN A TYPICAL COSTUME OF HIS NATIVE SICILY…. MICHELE AND I HAD A LOT OF COMMON INTERESTS… 1977--1980: all together in Miramare! ABDUS SALAM PAOLO BUDINICH Michele with Dirac, Kastler, Budinich, Hamende, et al. (1978) Simona Parrinello and Valentino Tosatti, Trieste, circa 1984 Roberto and Martina Car circa 1989 IN THE EARLY 80s…. MICHELE VISITS ANEES RAHMAN’S GROUP WHILE WE COLLABORATE…. ROBERTO GETS MORE AND MORE ENTANGLED WITH KOHN-SHAM DFT Yin Cohen PRL 1980 WINTER 1984-85: WORKING IN THE NIGHT… The mathematician plays a game in which he himself invents the rules while the physicist plays a game in which the rules are provided by nature, but as time goes on it becomes increasingly evident that the rules which the mathematician finds interesting are the same as those which nature has chosen. Paul A. M. Dirac In Ian Stewart, Why Beauty is Truth (2007), 279. 1985! “molecular dynamics” computer simulations of condensed matter: solids, liquids, etc Michele “density functional” electronic structure and total energy calculations of solids, etc Roberto IMPACT & CHALLENGES SOLIDS, LIQUIDS, SURFACES…. -

Finite Temperature Properties of Clusters by Replica Exchange Metadynamics: the Water Nonamer

Finite temperature properties of clusters by replica exchange metadynamics: the water nonamer ∗ Yingteng Zhai,† Alessandro Laio,‡ Erio Tosatti,‡ and Xin-Gao Gong ,† Key Laboratory for Computational Physical Sciences(MOE) and Surface Physics Laboratory & Department of Physics, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China, International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA), via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy., CNR-IOM Democritos National Simulation Centre, via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy., and Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), Strada Costiera 11, 34014 Trieste, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We introduce an approach for the accurate calculation of thermal properties of classical nanoclusters. Based on a recently developed enhanced sampling technique, replica exchange metadynamics, the method yields the true free energy of each relevant cluster structure, di- rectly sampling its basin and measuring its occupancy in full equilibrium. All entropy sources, whether vibrational, rotational anharmonic and especially configurational – the latter often for- gotten in many cluster studies – are automatically included. For the present demonstration we arXiv:1103.0972v1 [cond-mat.stat-mech] 4 Mar 2011 choose the water nonamer (H2O)9, an extremely simple cluster which nonetheless displays a sufficient complexity and interesting physics in its relevant structure spectrum. Within a stan- dard TIP4P potential description of water, we find that the nonamer second relevant structure ∗To whom correspondence should be addressed †Key Laboratory for Computational Physical Sciences(MOE) and Surface Physics Laboratory & Department of Physics, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China ‡International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA), via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy. ¶CNR-IOM Democritos National Simulation Centre, via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy. -

Ice and Victoria Buch: a Cold Surface and a Warm Heart Erio Tosatti SISSA, ICTP, and CNR/INFM Democritos, Trieste, Italy

Ice and Victoria Buch: a cold surface and a warm heart Erio Tosatti SISSA, ICTP, and CNR/INFM Democritos, Trieste, Italy Victoria Buch, who knew so much about ice and hydrogen bonds, was intrigued and fascinated by the possible physical states of the ice surface. She knew on one hand that it was only reasonable to expect the proton disorder of bulk ice to persist at the surface. She also on the other hand felt, or hoped, that the surface energetics should favor some new type of surface proton order, absent in bulk ice. To pursue this fragile dream, she stole time away from her heartier physico-chemical studies, and from her warm-hearted generous political battles within Israel, to collaborate with a surface theorist, whom she met by chance one summer in Lugano -- me. Me, who would contribute nothing more than some generic wisdom, and no actual hard calculations. Her own calculations, both Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo, eventually showed that in the cold ice surface not only the oxygen atoms would stay put and crystalline up until some 180 K, but showed that at low enough temperatures the protons too would order -- and that in spite of proton disorder in the underlying bulk! My own job ended up being to recognize that this surface order, 2x1 stripes formed by rows of "dangling hydrogens" and "dangling oxygens" (an old suggestion by Fletcher) could finally make sense of some unexplained helium scattering data obtained a decade earlier in Goettingen. Victoria and I were still collaborating, and spending hours on the phone at that, when her fatal disease came. -

![Arxiv:1608.08587V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 30 Aug 2016 PWA90 a Life Time of Emergence Editors: P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0771/arxiv-1608-08587v1-cond-mat-str-el-30-aug-2016-pwa90-a-life-time-of-emergence-editors-p-2820771.webp)

Arxiv:1608.08587V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 30 Aug 2016 PWA90 a Life Time of Emergence Editors: P

My Random Walks in Anderson's Garden ∗ G. Baskaran The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, C.I.T. Campus, Chennai 600 113, India & Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, ON, N2L 2Y6 Canada Abstract Anderson's Garden is a drawing presented to Philip W. Anderson on the eve of his 60th birthday celebration, in 1983. This cartoon (Fig. 1), whose author is unknown, succinctly depicts some of Andersons pre-1983 works, as a blooming garden. As an avid reader of Andersons papers, a random walk in Andersons garden had become a part of my routine since graduate school days. This was of immense help and prepared me for a wonderful collaboration with the gardener himself, on the resonating valence bond (RVB) theory of High Tc cuprates and quantum spin liquids, at Princeton. The result was bountiful - the first (RVB mean field) theory for i) quantum spin liquids, ii) emergent fermi surface in Mott insulators and iii) superconductivity in doped Mott insulators. Beyond mean field theory - i) emergent gauge fields, ii) Ginzburg Landau theory with RVB gauge fields, iii) prediction of superconducting dome, iv) an early identification and study of a non-fermi liquid normal state of cuprates and so on. Here I narrate this story, years of my gardening attempts and end with a brief summary of my theoretical efforts to extend RVB theory of superconductivity to encompass the recently observed very high Tc ∼ 203 K superconductivity in molecular solid H2S at high pressures ∼ 200 GPa. ∗ Closely follows an article published in arXiv:1608.08587v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 30 Aug 2016 PWA90 A Life Time of Emergence Editors: P. -

Glimpses of Greatness∗ a Personal View of P W Anderson (1923–2020)

GENERAL ARTICLE Glimpses of Greatness∗ A Personal View of P W Anderson (1923–2020) G Baskaran P W Anderson was a theoretical physicist. He won the No- bel Prize in 1977. He catalysed Nobel Prizes for several oth- ers. His career spanned 72 years of relentless research, filled with path-breaking contributions. He focussed on ‘here and now’ phenomena of inanimate materials and built theoreti- cal quantum models of lasting value. He communed with na- ture by contemplation and study of experimental results. As a G Baskaran is a theoretical founding father, he set agenda for the field of condensed mat- physicist. He studies a variety ter physics, for half a century. It is a growing fertile field now, of quantum phenomena, with a web of connection to different corners of science, tech- including theory and nology, and sometimes beyond. As a person, Anderson was mechanism of room-temperature remarkable. He was my long time collaborator since 1984. I superconductivity. He shares had a wonderful opportunity to join hands with him when he his time between The Institute initiated the resonating valence bond (RVB) theory of high- of Mathematical Sciences, temperature superconductivity in cuprates in early 1987. Chennai, Department of Physics of Indian Institute of It was 1986. I was talking to Anderson in his office at Prince- Technology Madras and ton. A young undergraduate walked in. Students knew that no Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, prior appointment was necessary to meet this Nobel Laureate in Waterloo, Canada. his office. The student elaborated on an idea he had. After a while I became impatient. -

Spin and Orbital Entanglement

Condensed Matter Physics in the City 2015 6th Hubbard Theory Consortium London Summer Programme in Condensed Matter Physics Week 2 (June 29 - July 2) Spin and orbital entanglement Monday, June 29: Senate House, Room 261, London, WC1E 7HU 09:30 - 10:00 Coffee/Tea 10:00 - 10:45 Peter Johnson (Brookhaven National Laboratory, US), title tbc 10:45 - 11:15 Discussion 11:15 - 11:30 Coffee/Tea 11:30 - 12:00 Yusuke Nomura (École Polytechnique, France), High-Tc s-wave superconductivity in fullerides induced by unusual synergy between strong correlations and phonons 12:00 - 12:15 Discussion Lunch Break 14:00 - 14:45 Gilbert Lonzarich (Cambridge, UK), Electron-electron and electron-hole pairing on the border of ferromagnetic and ferroelectric quantum phase transitions 14:45 - 15:00 Discussion 15:00 - 15:30 Hannah Irons (Kent University, UK), Neutron Scattering Signatures of the Entanglement Transition 15:30 - 15:45 Discussion 15:45 - 16:15 Coffee/Tea 16:15 - 16:45 Giacomo Mazza (SISSA, Italy), Electric-field driven insulator-to-metal transitions in orbitally polarized correlated systems 16:45 - 17:00 Discussion 17:00 - 17:30 Abolfazl Bayat (UCL, UK), Universal Single-Frequency Oscillations in a Quantum Impurity System After a Local Quench 17:30 - 17:45 Discussion ————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— Tuesday, June 30: Rutherford Appleton Laboratory 09:30 - 10:00 Coffee/Tea 10:00 - 10:45 Peter Johnson (Brookhaven National Laboratory, US), title tbc 10:45 - 11:15 Discussion 11:15 - 11:30 Coffee/Tea 11:30 - 12:00 Massimo Capone -

Kondo Conductance Across the Smallest Spin 1/2 Radical Molecule

Kondo conductance across the smallest spin 1/2 radical molecule Ryan Requista, Silvio Modestib, Pier Paolo Barusellia,c,d, Alexander Smogunove, Michele Fabrizioa,d, and Erio Tosattia,d,f,1 aCondensed Matter Sector, International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA), 34136 Trieste, Italy; bPhysics Department, University of Trieste, 34127 Trieste, Italy; cInstitute for Theoretical Physics, Technical University Dresden, 01069 Dresden, Germany; dNational Research Council (CNR-IOM Democritos), 34136 Trieste, Italy; eFrench Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), Saclay Institute of Matter and Radiation (IRAMIS), Laboratory of Physics and Chemistry of Surfaces and Interfaces (SPCSI), F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France; and fInternational Centre for Theoretical Physics, 34151 Trieste, Italy Contributed by Erio Tosatti, December 3, 2013 (sent for review October 3, 2013) Molecular contacts are generally poorly conducting because their quantitatively tested ab initio electronic structure-based approaches energy levels tend to lie far from the Fermi energy of the metal to Kondo conductance have so far restricted the theoretical work to contact, necessitating undesirably large gate and bias voltages the role of a posteriori support of STM and break junction zero bias in molecular electronics applications. Molecular radicals are an anomaly data. It is therefore important to achieve a first-principles exception because their partly filled orbitals undergo Kondo predictive capability of Kondo conductance anomalies across mo- screening, opening the way to electron passage even at zero bias. lecular radicals and ascertain its reliability. To that end, we put to Whereas that phenomenon has been experimentally demon- work a density functional theory and numerical renormalization strated for several complex organic radicals, quantitative theoret- group (DFT+NRG) method devised and implemented earlier in ical predictions have not been attempted so far. -

News from ICTP from the Efforts of Shobhana Narasimhan (JNCASR, Bangalore, India) and Elizabeth Simmons (Michigan State University, USA)

News from ICTP Beyond Bias: Women in Mathematical and Physical Sciences AUTUMN / WINTER 2013 / AUTUMN 136 2 Beyond Bias Women in Mathematical and Physical Sciences We have a hunger of the mind which asks for knowledge of all around us, and the more we gain, the more is our desire; the more we see, the more we are capable of seeing. Maria Mitchell (1818-1889), co-founder of the Amer- ican Association for the Advancement of Women and first woman to work as a professional astronomer. Taking Mitchell’s words to heart, ICTP offers you this newsletter issue of illuminating pieces on women in mathematical and physical sciences. Regardless of what country and culture they come from, these women share a hunger for knowledge and were kind enough to express how this hunger led them to pur- sue careers in physical or mathematical research, the scientific fields with the fewest women professionals. We were first inspired to dedicate this issue of News from ICTP from the efforts of Shobhana Narasimhan (JNCASR, Bangalore, India) and Elizabeth Simmons (Michigan State University, USA). They developed the idea for and organized the “Career Development Workshop for Women in Physics,” which ICTP hosted from 16 to 19 September (see story on page 4). The workshop addressed some of the obstacles wom- en in physics still battle today, despite the gradually growing number of professional women physicists around the world. The women in our newsletter pro- file articles—like Helen Quinn, Nana Shatashvili and Zohra Ben Lakhdar—reflect upon what some of these obstacles are and how to overcome them. -

Superconducting Chevrel Phase Pbmo $ {6} $ S $ {8} $ from First Principles

Superconducting Chevrel phase PbMo6S8 from first principles Giovanni Marini,1, 2 Antonio Sanna,3 Camilla Pellegrini,4 Christophe Bersier,5 Erio Tosatti,6, 7, 8 and Gianni Profeta9, 10 1Department of Physical and Chemical Sciences, University of L'Aquila, Via Vetoio 10, I-67100 L'Aquila Italy 2SPIN-CNR, University of L'Aquila, Via Vetoio 10, I-67100 L'Aquila Italy 3Max-Planck Institut f¨urMikrostrukturPhysik, Weinberg 2, 06120 Halle, Germany 4Department of Physics and Geology, University of Perugia, Via Pascoli 33, 06123 Perugia, Italy 5Max-Planck Institut f¨urMikrostrukturPhysik, Weinberg 2, 06120 Halle, (Germany) 6International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA), Via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy 7CNR-IOM Democritos National Simulation Center, Via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy 8The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), Strada Costiera 11, 34151 Trieste, Italy 9Department of Physical and Chemical Sciences, University of L'Aquila, Via Vetoio 10, I-67100 L'Aquila (Italy) 10SPIN-CNR, University of L'Aquila, Via Vetoio 10, I-67100 L'Aquila (Italy) Chevrel ternary superconductors show an intriguing coexistence of molecular aspects, large electron-phonon and electron-electron correlations, which to some extent still impedes their quan- titative understanding. We present a first principles study on the prototypical Chevrel compound PbMo6S8, including electronic, structural and vibrational properties at zero and high pressure. We confirm the presence of an extremely strong electron-phonon coupling, linked to the proximity to a R3-P1 structural phase transition, which weakens as the system, upon applied pressures, is driven away from the phase boundary. A detailed description of the superconducting state is obtained by means of fully ab initio superconducting density functional theory (SCDFT).