The Symbolism of the Lycurgus Cup1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflecting Antiquity Explores the Rediscovery of Roman Glass and Its Influence on Modern Glass Production

Reflecting Antiquity explores the rediscovery of Roman glass and its influence on modern glass production. It brings together 112 objects from more than 24 lenders, featuring ancient Roman originals as well as the modern replicas they inspired. Following are some of the highlights on view in the exhibition. Portland Vase Base Disk The Portland Vase is the most important and famous work of cameo glass to have survived from ancient Rome. Modern analysis of the vase, with special attention to the elongation of the bubbles preserved in the lower body, suggest that it was originally shaped as an amphora (storage vessel) with a pointed base. At some point in antiquity, the vessel suffered some damage and acquired this replacement disk. The male figure and the foliage on the disk were not carved by the same Unknown artist that created the mythological frieze on the vase. Wearing a Phrygian cap Portland Vase Base Disk Roman, 25 B.C.–A.D. 25 and pointing to his mouth in a gesture of uncertainty, the young man is Paris, a Glass Object: Diam.: 12.2 cm (4 13/16 in.) prince of Troy who chose Aphrodite over Hera and Athena as the most beautiful British Museum. London, England GR1945.9-27.2 goddess on Mount Olympus. It is clear from the way the image is truncated that VEX.2007.3.1 it was cut from a larger composition, presumably depicting the Judgment of Paris. The Great Tazza A masterpiece of cameo-glass carving, this footed bowl (tazza) consists of five layers of glass: semiopaque green encased in opaque white, green, a second white, and pink. -

A View of the Horse from the Classical Perspective the Penn Museum Collection by Donald White

A View of the Horse from the Classical Perspective The Penn Museum Collection by donald white quus caballus is handsomely stabled in tive how-to manual On Horsemanship (“The tail and mane the University of Pennsylvania Museum of should be washed, to keep the hairs growing, as the tail is used Archaeology and Anthropology. From the to swat insects and the mane may be grabbed by the rider Chinese Rotunda’s masterpiece reliefs portray- more easily if long.”) all the way down to the 9th century AD ing two horses of the Chinese emperor Taizong Corpus of Greek Horse Veterinarians, which itemizes drugs for Eto Edward S. Curtis’s iconic American Indian photographs curing equine ailments as well as listing vets by name, Greek housed in the Museum’s Archives, horses stand with man and Roman literature is filled with equine references. One in nearly every culture and time-frame represented in the recalls the cynical utterance of the 5th century BC lyric poet Museum’s Collection (pre-Columbian America and the Xenophanes from the Asia Minor city of Colophon: “But if northern polar region being perhaps the two most obvious cattle and horses and lions had hands, or were able to do the exceptions). Examples drawn from the more than 30,000 work that men can, horses would draw the forms of the gods like Greek, Roman, and Etruscan vases, sculptures, and other horses” (emphasis added by author). objects in the Museum’s Mediterranean Section serve here as The partnership between horse and master in antiquity rested a lens through which to view some of the notable roles the on many factors; perhaps the most important was that the horse horse played in the classical Mediterranean world. -

Chapter Five: Cupid and Psyche

Chapter Five: Cupid and Psyche (from Mythology for Today Hamilton’s Mythology) 1. Venus becomes jealous because Psyche’s surpassing beauty has transfixed all the mortals, so that they forget Venus, and neglect her temples and altars. 2. Venus plans to have her son, Cupid, shoot Psyche with a love arrow, so that Psyche will fall in love with a hideous creature. Venus’ plan fails because Cupid himself falls in love with the beautiful Psyche. 3. Psyche’s father believes that he must leave her on the summit to be claimed by her serpent‐husband, for this is what he has been told by the Oracle of Apollo. However, the truth is that Cupid has arranged this himself, so that he can carry Psyche away as his own bride. 4. Her sisters become jealous of Psyche’s superior riches and treasures. 5. Psyche is torn between her love for and her faith in her husband, and the doubt and fear her sisters cause her to feel. She is unable to live with the uncertainty of not knowing the truth. 6. When Psyche sees that her husband is a beautiful youth, she feels too ashamed of her suspicion that she is about to plunge the knife intended for him into her own breast. However, her hand trembles and the knife falls. This faltering saves her own life, but also causes her to drip some lamp oil on Cupid, who sees that she has betrayed him and runs away. 7. Psyche is made to separate by kind a huge mixed mass of tiny grains; ants separate them for her. -

Names of Botanical Genera Inspired by Mythology

Names of botanical genera inspired by mythology Iliana Ilieva * University of Forestry, Sofia, Bulgaria. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2021, 14(03), 008–018 Publication history: Received on 16 January 2021; revised on 15 February 2021; accepted on 17 February 2021 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2021.14.3.0050 Abstract The present article is a part of the project "Linguistic structure of binomial botanical denominations". It explores the denominations of botanical genera that originate from the names of different mythological characters – deities, heroes as well as some gods’ attributes. The examined names are picked based on “Conspectus of the Bulgarian vascular flora”, Sofia, 2012. The names of the plants are arranged in alphabetical order. Beside each Latin name is indicated its English common name and the family that the particular genus belongs to. The article examines the etymology of each name, adding a short account of the myth based on which the name itself is created. An index of ancient authors at the end of the article includes the writers whose works have been used to clarify the etymology of botanical genera names. Keywords: Botanical genera names; Etymology; Mythology 1. Introduction The present research is a part of the larger project "Linguistic structure of binomial botanical denominations", based on “Conspectus of the Bulgarian vascular flora”, Sofia, 2012 [1]. The article deals with the botanical genera appellations that originate from the names of different mythological figures – deities, heroes as well as some gods’ attributes. According to ICBN (International Code of Botanical Nomenclature), "The name of a genus is a noun in the nominative singular, or a word treated as such, and is written with an initial capital letter (see Art. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Nautilus-Cup

Minneapolis Institute of Arts Accessions Proposal Curator: Eike D. Schmidt Department: DATS Date: 6/2/2011 1. Description and Summary of Object or Group of Objects: Loan Number: L2011.52 Artist/Maker: Unknown (Northern Germany, c. 1660-1680) Title/Object: Nautilus Cup Date: circa 1660-1680 Medium: nautilus shell; silver, parcel-gilt Dimensions: 15 x 7 ¼ x 4 ¼ in. (38 x 18.5 x 11 cm) Signed, marked or inscribed: Unmarked. Country of manufacture: Germany Vendor/Donor: Galerie J. Kugel, Paris Credit Line: Gift of funds from Mary Agnes and Al McQuinn Present Location: With the dealer in Maastricht, The Netherlands 2. Artist, Style, and explanation of the proposed object: From the end of the 16th century, Nautilus shells from the Indo-Pacific Ocean were imported into Europe on a regular basis, where they were admired for their exotic origins and geometric perfection. The fact that their interior chambers follow a logarithmic spiral was interpreted in early modern thought as evidence for the theory that nature from its greatest manifestations (macrocosm) to its smallest details (microcosm) follows a thorough plan. They were seen as proof of the convergence of the bodily and spiritual worlds (here: invertebrate zoology and mathmatics), and often ultimately of the existence of God. Whereas a few nautilus shells were made into liturgical objects (incense burners), the vast majority were mounted as secular drinking vessels by, generally, outfitting them with mounts of silver, gilt silver and gold figures alluding to the Sea or the element of water (as the nautilus’s original habitat). Silver-mounted nautilus shells were among the most characteristic products of the famous gold- and silversmithing workshops of Augsburg and Nuremberg in Southern Germany and were sought after by collector all over Europe. -

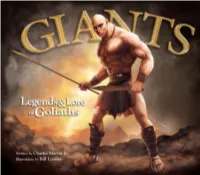

Giants: Legends & Lore of Goliaths

PERHAPS MYTHOLOGY CONTAINS MORE TRUTH THAN WE REALIZE! The word “myth” has come to mean “fiction” in our minds, and so some people take Bible accounts, Aesop’s fables, and Greek myths and place them all in the same category. But what if some of the old legends are true? Rather than dismiss these narratives, perhaps we should investigate them. In this case, the world is filled with giant legends that speak of heroes and wars. In this highly engaging book of giants you will discover ? Unique glimpses into the ancient accounts of giants from around the world @ What does the Bible say about giants? ? Full-color artistry developed in an interactive format with fold outs and flaps, booklets, and more! @ A spectacular center spread stretching 4-feet across! It is fascinating that the ancient world agreed on many aspects of the Martin Bible, one of these being that early in the history of mankind, a race of violent, yet intelligent giants walked the earth, were destroyed by the Flood. Through historical records, the pre-Flood and post-Flood worlds are reconstructed, with giants re-emerging in and around Israel, and you’ll see one more reason that the Bible can be trusted. RELIGION/Biblical Studies/General JUVENILE NONFICTION/Religious/ Christian/General $18.99 U.S. ISBN-13: 978-0-89051-864-9 EAN First printing: June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Master Books. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used Odysseus Blinds Polyphemus or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews. -

Roman Coins – Mass Media for Image Cultivation

Roman Coins – Mass Media for Image Cultivation Unlike modern coins, Roman money was characterized by an enormous diversity of coin images. This reflected not so much the desire for change, however, but rather an often very purposeful policy of concrete self-interests. At the time of the Roman Republic, coins were issued on behalf of the senate by a committee of moneyers. These men decided independently what motifs their coins were to bear, and, from the late 2nd century BC, used this liberty often for family propaganda. Later, during the time of the Firs and second triumvirate (60 to 32 BC), coins were issued by several powerful Romans or their adherents. These pieces were not republican any more, but imperatorial, and used mainly for the representation of political dispositions and ambitions. In imperial times finally (from 27 BC), the rulers of Rome were in charge of the issuance of money. Naturally, they used the large Roman coins for the artful conversion of political propaganda and self-manifestation as well. 1 von 20 www.sunflower.ch Roman Republic, L. Caecilius Metellus Diadematur (or Delmaticus), Denarius, 128 BC Denomination: Denarius Mint Authority: Moneyer Lucius Caecilius Metellus Diadematus (?) Mint: Rome Year of Issue: -128 Weight (g): 3.94 Diameter (mm): 18.0 Material: Silver Owner: Sunflower Foundation This denarius bears on the obverse a traditional motif, the head of Roma, the goddess and personification of Rome, wearing a winged attic helmet; behind her is the mark XVI for the value of 16 asses. The reverse depicts a goddess driving a biga, a two-horse racing chariot. -

Roman Art Kindle

ROMAN ART PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Zanker | 216 pages | 10 Jan 2012 | Getty Trust Publications | 9781606061015 | English | Santa Monica CA, United States Roman Art PDF Book If you don't know about Paracas textiles Construction of the Baths of Diocletian , for instance, monopolised the entire brick industry of Rome, for several years. Roman aqueducts , also based on the arch, were commonplace in the empire and essential transporters of water to large urban areas. The Romans also made frequent use of the semicircular arch, typically without resorting to mortar: relying instead on the precision of their stonework. The heads of the Marcus Aurelius figures are larger than normal, to show off their facial expressions. However it never lost its distinctive character, especially notable in such fields as architecture, portraiture, and historical relief. This led to a popular trend among the ancient Romans of including one or more such statues in the gardens and houses of wealthier patrons. With the authenticity of the medallion more firmly established, Joseph Breck was prepared to propose a late 3rd to early 4th century date for all of the brushed technique cobalt blue-backed portrait medallions, some of which also had Greek inscriptions in the Alexandrian dialect. They also served an important unifying force. Useing vivid colours it simulates the appearance of marble. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Sculpture: Types and Characteristics. A higher relief is used, permitting greater contrast between light and shadow. Further information: Roman portraiture. As another example of the lost "Golden Age", he singled out Peiraikos , "whose artistry is surpassed by only a very few But flagship buildings with domes were far from being the only architectural masterpieces built by Ancient Rome. -

Contextualizing the Archaeometric Analysis of Roman Glass

Contextualizing the Archaeometric Analysis of Roman Glass A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati Department of Classics McMicken College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts August 2015 by Christopher J. Hayward BA, BSc University of Auckland 2012 Committee: Dr. Barbara Burrell (Chair) Dr. Kathleen Lynch 1 Abstract This thesis is a review of recent archaeometric studies on glass of the Roman Empire, intended for an audience of classical archaeologists. It discusses the physical and chemical properties of glass, and the way these define both its use in ancient times and the analytical options available to us today. It also discusses Roman glass as a class of artifacts, the product of technological developments in glassmaking with their ultimate roots in the Bronze Age, and of the particular socioeconomic conditions created by Roman political dominance in the classical Mediterranean. The principal aim of this thesis is to contextualize archaeometric analyses of Roman glass in a way that will make plain, to an archaeologically trained audience that does not necessarily have a history of close involvement with archaeometric work, the importance of recent results for our understanding of the Roman world, and the potential of future studies to add to this. 2 3 Acknowledgements This thesis, like any, has been something of an ordeal. For my continued life and sanity throughout the writing process, I am eternally grateful to my family, and to friends both near and far. Particular thanks are owed to my supervisors, Barbara Burrell and Kathleen Lynch, for their unending patience, insightful comments, and keen-eyed proofreading; to my parents, Julie and Greg Hayward, for their absolute faith in my abilities; to my colleagues, Kyle Helms and Carol Hershenson, for their constant support and encouragement; and to my best friend, James Crooks, for his willingness to endure the brunt of my every breakdown, great or small. -

Soup in a Cup/Bowl Served with Crackers Made from Meadowlark Organics 4.5/6.5

Soup in a Cup/Bowl Served with Crackers made from Meadowlark Organics 4.5/6.5 Wisconsin Driftless Cheese Plate for Two 16 A selection of Upland’s Pleasant Ridge Reserve, Billy Blue and Benedictine Mixed-Milk cheese, both from Carr Valley. Served with Crackers made from Meadowlark Organic Grains, Apricot-Cherry Compote, and Toasted Pecans Corned Beef and Kimchi Cabbage 14 House-Cured Cates Beef Brisket served with Spicy Kimchi, and served over Taliesin Estate Smashed Potatoes laced with a hint of Marieke Gouda. Entrée Salad of the Moment Can be prepared Vegetarian / Vegan 12 Estate Greens and Herbs, local Wheatberries, Vegetables, and DreamFarm Chevre Cheese dressed with our Seasonal Pesto and Vinaigrette of the Moment Cates Farm Beef Cheeseburger* Nowhere near Vegetarian 12 Third-Pound Ground Beef grilled and served on a toasted Brioche Roll with Red Onion Jam and Marieke Gouda Cheese with Foenegreek Seed and served with choice of Russet Fries, Leafy Greens with an Herb Vinaigrette, or our Seasonal Side Grilled Cheese Vegetarian 10 Hook’s Aged Cheddar Cheese on Multi-grain Bread with a Seasonal Dipping Sauce, served with choice of Russet Fries, Leafy Greens with an Herb Vinaigrette, or our Seasonal Side Uplands Cheese Puff Salad Vegetarian 10 Pleasant Ridge Reserve Cheese Baked into a crispy Popover with Spring Lettuces and Whole Herbs, lightly dressed with Lemon Vinaigrette House-Cut Russet Fries with Seasonal Dipping Sauce 5 Side Salad with Herb Vinaigrette 4 Seasonal Side Dish 4 Add Seven Seeds Farm Chicken Spring Green, WI 5 Split Plate Charge 2 House Baked Cookies 1 Chocolate Chip, Oatmeal Raisin, Mixed Nut, or Sorghum Cookies Chocolate Pot de Crème Gluten Free 6 Belgian Milk Chocolate melted with Creamy Coconut Crème and infused with Spring Green’s Brewhaha Coffee Lemon Posset Gluten Free 4 Sweet Clotted Cream Infused with Lemon and topped with Berries Harvest Fruit Tartlette Vegetarian 4 Sweetened Quark Cheese whipped with Coriander and nested in a flaky crust and topped with seasonal fruit and a Rosemary Infused Honey Drizzle . -

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique Copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS

FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS VARVAKEION STATUETTE Antique copy of the Athena of Phidias National Museum, Athens FAVORITE GREEK MYTHS BY LILIAN STOUGHTON HYDE YESTERDAY’S CLASSICS CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA Cover and arrangement © 2008 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC. Th is edition, fi rst published in 2008 by Yesterday’s Classics, an imprint of Yesterday’s Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by D. C. Heath and Company in 1904. For the complete listing of the books that are published by Yesterday’s Classics, please visit www.yesterdaysclassics.com. Yesterday’s Classics is the publishing arm of the Baldwin Online Children’s Literature Project which presents the complete text of hundreds of classic books for children at www.mainlesson.com. ISBN-10: 1-59915-261-4 ISBN-13: 978-1-59915-261-5 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC PO Box 3418 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 PREFACE In the preparation of this book, the aim has been to present in a manner suited to young readers the Greek myths that have been world favorites through the centuries, and that have in some measure exercised a formative infl uence on literature and the fi ne arts in many countries. While a knowledge of these myths is undoubtedly necessary to a clear understanding of much in literature and the arts, yet it is not for this reason alone that they have been selected; the myths that have appealed to the poets, the painters, and the sculptors for so many ages are the very ones that have the greatest depth of meaning, and that are the most beautiful and the best worth telling.