Red Grouse Species Action Plan 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunting and Game Preservation Act

HUNTING AND GAME PRESERVATION ACT Prom. SG. 78/26 Sep 2000, amend. SG. 26/20 Mar 2001, amend. SG. 77/9 Aug 2002, amend. SG. 79/16 Aug 2002, amend. SG. 88/4 Nov 2005, amend. SG. 82/10 Oct 2006, amend. SG. 108/29 Dec 2006, amend. SG. 64/7 Aug 2007, amend. SG. 43/29 Apr 2008, amend. SG. 67/29 Jul 2008, amend. SG. 69/5 Aug 2008, amend. SG. 91/21 Oct 2008, amend. SG. 6/23 Jan 2009, amend. SG. 80/9 Oct 2009, amend. SG. 92/20 Nov 2009, amend. SG. 73/17 Sep 2010, amend. SG. 89/12 Nov 2010, amend. SG. 8/25 Jan 2011, amend. SG. 19/8 Mar 2011, amend. SG. 39/20 May 2011, amend. SG. 77/4 Oct 2011, amend. SG. 38/18 May 2012, amend. SG. 60/7 Aug 2012, amend. SG. 77/9 Oct 2012, amend. SG. 102/21 Dec 2012, amend. SG. 15/15 Feb 2013, amend. SG. 62/12 Jul 2013, amend. SG. 60/7 Aug 2015, amend. SG. 14/19 Feb 2016, amend. SG. 58/18 Jul 2017, amend. SG. 63/4 Aug 2017, amend. and suppl. SG. 17/23 Feb 2018, suppl. SG. 61/24 Jul 2018, suppl. SG. 77/18 Sep 2018, amend. and suppl. SG. 37/7 May 2019, amend. and suppl. SG. 74/20 Sep 2019 Chapter one. GENERAL PROVISIONS Art. 1. The Act shall provide the relations connected with the ownership, preservation and management of the game, the organisation of hunting economy, the right to hunt and the trade with game and game products. -

Donegal Winter Climbing

1 A climbers guide to Donegal Winter Climbing By Iain Miller www.uniqueascent.ie 2 Crag Index Muckish Mountain 4 Mac Uchta 8 Errigal 10 Maumlack 13 Poison Glen 15 Slieve Snaght 17 Horseshoe Corrie (Lough Barra) 19 Bluestacks (N) 22 Bluestacks (S) 22 www.uniqueascent.ie 3 Winter Climbing in Donegal. Winter climbing in the County of Donegal in the North West of Ireland is quite simply outstanding, alas it has a very fleeting window of opportunity. Due to it’s coastal position and relatively low lying mountains good winter conditions in Donegal are a rare commodity indeed. Usually temperatures have to be below 0 for 5 days consecutively, and down to -5 at night, and an ill timed dump of snow can spoil it all. To take advantage of these fleeting conditions you have to drop everything, and brave the inevitably appalling road conditions to get there, for be assured, it won’t last! When Donegal does come into prime Winter condition the crux of your days climbing will without a doubt be travelling by road throughout the county. In this guide I have tried to only use National primary and secondary roads as a means to travel and access. There are of course many regional and third class roads which provide much closer access to the mountains but under winter conditions these can very quickly become unpassable. The first recorded winter climbing I am aware of, was done in the Horsehoe Corrie in the early seventies and since then barely a couple of new routes have been logged anywhere in Donegal each decade since that! It was the winter of 2009/2010 that one of the coldest and longest winters in recorded history occurred with over 6 weeks of minus temperatures and snowdrifts of up to 12m in the Donegal uplands. -

The Wild Rabbit: Plague, Polices and Pestilence in England and Wales, 1931–1955

The wild rabbit: plague, polices and pestilence in England and Wales, 1931–1955 by John Martin Abstract Since the eighteenth century the rabbit has occupied an ambivalent position in the countryside. Not only were they of sporting value but they were also valued for their meat and pelt. Attitudes to the rabbit altered though over the first half of the century, and this paper traces their redefinition as vermin. By the 1930s, it was appreciated that wild rabbits were Britain’s most serious vertebrate pest of cereal crops and grassland and that their numbers were having a significant effect on agricultural output. Government took steps to destroy rabbits from 1938 and launched campaigns against them during wartime, when rabbit was once again a form of meat. Thereafter government attitudes to the rabbit hardened, but it was not until the mid-1950s that pestilence in the form of a deadly virus, myxomatosis, precipitated an unprecedented decline in their population. The unprecedented decline in the European rabbit Oryctolagus( cuniculus) in the mid- twentieth century is one of the most remarkable ecological changes to have taken place in Britain. Following the introduction of myxomatosis into Britain in September 1953 at Bough Beech near Edenbridge in Kent, mortality rates in excess of 99.9 per cent were recorded in a number of affected areas.1 Indeed, in December 1954, the highly respected naturalist Robin Lockley speculated that 1955 would constitute ‘zero hour for the rabbit’, with numbers being lower by the end of the year than at any time since the eleventh century.2 In spite of the rapid increases in output and productivity which British agriculture experienced in the post-myxomatosis era, the importance of the disease as a causal factor in raising agricultural output has been largely ignored by agricultural historians.3 The academic neglect of the rabbit as a factor influencing productivity is even more apparent in respect of the pre-myxomatosis era, particularly the period before the Second World War. -

Driven Grouse Shooting

Driven grouse shooting RSPB Council updated our previous policy on driven grouse shooting in October 2020. Our policy is to support licensing of driven grouse shooting across the UK, following expected progress on this issue in Scotland in 2020. Unless substantial progress (including effective licensing, stopping raptor killing, cessation of burning on peat soils, and banning use of lead ammunition) is made in reforming driven grouse shooting by 2025 in line with RSPB principles for sustainable gamebird shooting, we will consequently call on governments to introduce a specific ban on driven grouse shooting. Background Driven grouse shooting is defined as where shooters sit in lines of grouse butts on open moorland, and red grouse are then driven by beaters and dogs over the guns to shoot. The activity usually involves shooting large grouse “bags” (where large numbers of grouse are shot in a day). It is a unique hunting type to the UK (mainly England and Scotland) and shooters will pay large sums of money for a day’s shooting. Typically, gamekeepers are employed to kill predators that eat grouse; heather is burned to create young heather (the main foodplant of red grouse); and other additional management techniques are employed to produce as many red grouse as possible for shooting. The red grouse shooting season opens on the 12 August (“the Glorious Twelfth”). The alternative walked up grouse shooting involves a small number of shooters accompanied by dogs. They generally take small and sustainable numbers of grouse, as walked up shooting is more about the hunting experience. This is much less of a conservation issue for us. -

NPWS Regional Contacts

National Parks & Wildlife Service LoCall 1890 383 000 90 King Street North Website www.npws.ie Smithfield Email [email protected] Dublin 7 D07 N7CV Contact Information National Parks and Nature Reserves Ballycroy National Park, [email protected] (098) 49 996 Lagduff More, Ballycroy, Westport, Co. Mayo Burren National Park, [email protected] (065) 682 7693 NEPS Building, St. Francis Street, Ennis, Co. Clare Connemara National Park, [email protected] (095) 41 054 Letterfrack, Co. Galway Coole Park Nature Reserve, [email protected] (091) 631 804 Gort, Co. Galway Glenveagh National Park, [email protected] (076) 100 2537 Church Hill, Letterkenny, Co. Donegal Killarney National Park, [email protected] (065) 663 1440 Muckross House, Killarney, Co. Kerry Wexford Wildfowl Reserve, [email protected] (076) 100 2660 North Slob, Wexford Wicklow Mountains National Park, [email protected] (0404) 45 425 Kilafin, Laragh, Co. Wicklow Last updated 11 May 2020 Page 1 Regional Offices Eastern Division Divisional Manager (076) 100 2654 Divisional Ecologist (076) 100 2622 North Eastern Region Areas covered Regional Manager (076) 100 2591 Dublin, Kildare, Laois, Louth, District Conservation Officer (Kildare, Laois, Offaly) (076) 100 2594 Meath, Offaly District Conservation Officer (Dublin, Louth, Meath) (076) 100 2593 South Eastern Region Areas covered Regional Office (076) 100 2667 Carlow, Kilkenny, Wexford, Regional Manager (076) 100 2671 Wicklow (including Wicklow -

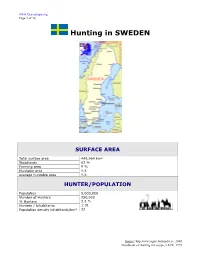

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Inspector's Report PL27.247982

Inspector’s Report PL27.247982 Development House, vehicular access, driveway & wastewater treatment plant. Location Barmamire, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow Planning Authority Wicklow Co. Council. Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 16/815 Applicant Mary King Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Refuse permission Type of Appeal First Party Appellant Mary King Observer None Date of Site Inspection 20/4/17 Inspector Siobhan Carroll PL27.247982 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 13 1.0 Site Location and Description 1.1. The appeal site is located in the townland of Barmamire, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow. It is situated circa 4.8km to the west of Enniskerry. It is accessed off the L1011 and then via the L5041 which forms part of the Wicklow Way. The site is located at circa the 250m contour at the eastern road side boundary. The site levels fall to circa 230m contour to the south-western corner. There are extensive views out over the Glencree River valley and towards Glencullen Mountain to the north, Powerscourt Mountain to the south and Glencree to the west. 1.2. The site has a stated area of 1.74 hectares and it comprises a grassed field. It contains sections of gorse. An area of semi-mature trees and saplings have been planted on the northern side of the site. The adjoining lands to the north and west are under forestry. 2.0 Proposed Development 2.1. Permission is sought for a house, vehicular access, driveway & wastewater treatment plant. The main features of the scheme are as follows; • Site area – 1.74 hectares • Dwelling with floor area of 249sq m • Ridge height of between 5m and 8.7m • Wasterwater treatment plant • Bored Well 3.0 Planning Authority Decision 3.1. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Listing and Index of Evening Herald Articles 1938 ~ 1975 by J

Listing and Index of Evening Herald Articles 1938 ~ 1975 by J. B. Malone on Walks ~ Cycles ~ Drives compiled by Frank Tracy SOUTH DUBLIN LIBRARIES - OCTOBER 2014 SOUTH DUBLIN LIBRARIES - OCTOBER 2014 Listing and Index of Evening Herald Articles 1938 ~ 1975 by J. B. Malone on Walks ~ Cycles ~ Drives compiled by Frank Tracy SOUTH DUBLIN LIBRARIES - OCTOBER 2014 Copyright 2014 Local Studies Section South Dublin Libraries ISBN 978-0-9575115-5-2 Design and Layout by Sinéad Rafferty Printed in Ireland by GRAPHPRINT LTD Unit A9 Calmount Business Park Dublin 12 Published October 2014 by: Local Studies Section South Dublin Libraries Headquarters Local Studies Section South Dublin Libraries Headquarters County Library Unit 1 County Hall Square Industrial Complex Town Centre Town Centre Tallaght Tallaght Dublin 24 Dublin 24 Phone 353 (0)1 462 0073 Phone 353 (0)1 459 7834 Email: [email protected] Fax 353 (0)1 459 7872 www.southdublin.ie www.southdublinlibraries.ie Contents Page Foreword from Mayor Fintan Warfield ..............................................................................5 Introduction .......................................................................................................................7 Listing of Evening Herald Articles 1938 – 1975 .......................................................9-133 Index - Mountains ..................................................................................................134-137 Index - Some Popular Locations .................................................................................. -

ECOS 37-2-60 Reintroductions and Releases on the Isle Of

ECOS 37(2) 2016 ECOS 37(2) 2016 Reintroductions and releases on the Isle of Man Lessons from recent retreats Recent proposals for the release of white-tailed sea eagles and red squirrels on the Isle of Man received very different treatment, perhaps reflecting public perception of the animals and the public profile of the proponents, but also the political landscape of the island. NICK PINDER The Manx legal context The Isle of Man is a Crown dependency outside the EU but inside a common customs union with the United Kingdom. The Island can request that Westminster’s laws are extended to it but usually the Island passes its own laws which it promulgates at the annual Tynwald ceremony. Since it has a special relationship with the European Union, under Protocol 3, EU legislation covering agricultural and other trade is Point of Ayre: The Ayres is a large area of coastal heath and dune grassland in the north of the Isle of Mann usually translated into Manx law, as is UK law affecting customs controls. The 1980 island and location of the only National Nature Reserve. Endangered Species Act was therefore swiftly adopted in the Isle of Man but the Photo: Nick Pinder Wildlife and Countryside Act of the same year was not. A test for the legislation came in the early 1990s when some fox carcases turned When I arrived on the Isle of Man in 1987, the only wildlife legislation was a up. One was allegedly run over and then someone came forward having shot two dated Protection of Birds Act (1932-1975) but the newly formed Department of adults at a den site and dug up several cubs. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

List of Irish Mountain Passes

List of Irish Mountain Passes The following document is a list of mountain passes and similar features extracted from the gazetteer, Irish Landscape Names. Please consult the full document (also available at Mountain Views) for the abbreviations of sources, symbols and conventions adopted. The list was compiled during the month of June 2020 and comprises more than eighty Irish passes and cols, including both vehicular passes and pedestrian saddles. There were thousands of features that could have been included, but since I intended this as part of a gazetteer of place-names in the Irish mountain landscape, I had to be selective and decided to focus on those which have names and are of importance to walkers, either as a starting point for a route or as a way of accessing summits. Some heights are approximate due to the lack of a spot height on maps. Certain features have not been categorised as passes, such as Barnesmore Gap, Doo Lough Pass and Ballaghaneary because they did not fulfil geographical criteria for various reasons which are explained under the entry for the individual feature. They have, however, been included in the list as important features in the mountain landscape. Paul Tempan, July 2020 Anglicised Name Irish Name Irish Name, Source and Notes on Feature and Place-Name Range / County Grid Ref. Heig OSI Meaning Region ht Disco very Map Sheet Ballaghbeama Bealach Béime Ir. Bealach Béime Ballaghbeama is one of Ireland’s wildest passes. It is Dunkerron Kerry V754 781 260 78 (pass, motor) [logainm.ie], ‘pass of the extremely steep on both sides, with barely any level Mountains ground to park a car at the summit.