Aphra Behn and Susanna Centlivre: a Materialist- Feminist Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aphra Behn: Libertine? Or Marital Reformer?

Aphra Behn: Libertine? Or Marital Reformer? A History, with an Examination of Several Plays and Fictions By Florence Irene Munson Rouse in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master ofArts in English May 12, 1998 Thesis Adviser: Iit. William C. Home Aphra Behn: Libertine? Or Marital Refiormer? A Histqry with an Examinjation ofSeveral Prays and Fictions This Thesis for the M.A. degree in English by Florence Irene Munson Rouse has been approved for the Graduate Faculty by Supervisor: Reader: Date: Aphra Behn was an important female vliter in the Restoration era. She wrote twenty or more plays which were produced on the London stage, as well as a dozen or more novels, several volumes ofpoetry, and numerous translations. She was the flrSt WOman VIiter tO Cam her living byher pen. After she became successful, a concerted attack was made on her, alleging a libertine life and inmoral behavior. Gradually, her life work was expunged from the seventeenth-century literary canon based on this alleged lifestyle. Since little factual information is available about her her life, critics have been happyto invent various scenarios. The only true understanding ofher attitudes is found in the reading ofher plays, not to establish autobiographical facts, but to understandher attitudes. Based on the evidence inher many depictions oflibertine men in her satirical comedies, she disliked male libertines and foundtheir behavior deplorable. in plays and poetry, her longing for a new social order in which men and women micht love andrespect one another in freely chosen wedlock is the dominant theme. Far from being libertine, Aphra Behn is an early pioneer for companionate marriage. -

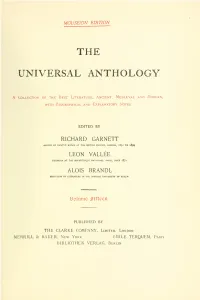

The Universal Anthology

MOUSEION EDITION THE UNIVERSAL ANTHOLOGY A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Medieval and Modern, WITH Biographical and Explanatory Notes EDITED BY RICHARD GARNETT KEEPER OF PRINTED BOOKS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, 185I TO 1899 LEON VALLEE LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQJJE NATIONALE, PARIS, SINCE I87I ALOIS BRANDL PKOFESSOR OF LITERATURE IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OP BERLIN IDoluine ififteen PUBLISHED BY THE CLARKE COMPANY, Limited, London MERRILL & BAKER. New York EMILE TERQUEM. Paris BIBLIOTHEK VERLAG, Berlin Entered at Stationers' Hall London, 1899 Droits de reproduction et da traduction reserve Paris, 1899 Alle rechte, insbesondere das der Ubersetzung, vorbehalten Berlin, 1899 Proprieta Letieraria, Riservate tutti i divitti Rome, 1899 Copyright 1899 by Richard Garnett IMMORALITY OF THE ENGLISH STAGE. 347 Young Fashion — Hell and Furies, is this to be borne ? Lory — Faith, sir, I cou'd almost have given him a knock o' th' pate myself. A Shoet View of the IMMORALITY AND PROFANENESS OF THE ENG- LISH STAGE. By JEREMY COLLIER. [Jeremy Collier, reformer, was bom in Cambridgeshire, England, in 1650. He was educated at Cambridge, became a clergyman, and was a " nonjuror" after the Revolution ; not only refusing the oath, but twice imprisoned, once for a pamphlet denying that James had abdicated, and once for treasonable corre- spondence. In 1696 he was outlawed for absolving on the scaffold two conspira- tors hanged for attempting William's life ; and though he returned later and lived unmolested in London, the sentence was never rescinded. Besides polemics and moral essays, he wrote a cyclopedia and an " Ecclesiastical IILstory of Great Britain," and translated Moreri's Dictionary. -

FRENCH INFLUENCES on ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE a Thesis

FRENCH INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of A the requirements for the Degree 2oK A A Master of Arts * In Drama by Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California Spring 2016 Copyright by Anne Melissa Potter 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read French Influences on English Restoration Theatre by Anne Melissa Potter, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: Drama at San Francisco State University. Bruce Avery, Ph.D. < —•— Professor of Drama "'"-J FRENCH INFLUENCES ON RESTORATION THEATRE Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California 2016 This project will examine a small group of Restoration plays based on French sources. It will examine how and why the English plays differ from their French sources. This project will pay special attention to the role that women played in the development of the Restoration theatre both as playwrights and actresses. It will also examine to what extent French influences were instrumental in how women develop English drama. I certify that the abstract rrect representation of the content of this thesis PREFACE In this thesis all of the translations are my own and are located in the footnote preceding the reference. I have cited plays in the way that is most helpful as regards each play. In plays for which I have act, scene and line numbers I have cited them, using that information. For example: I.ii.241-244. -

Studies in the Work of Colley Cibber

BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS HUMANISTIC STUDIES Vol. 1 October 1, 1912 No. 1 STUDIES IN THE WORK OF COLLEY CIBBER BY DE WITT C.:'CROISSANT, PH.D. A ssistant Professor of English Language in the University of Kansas LAWRENCE, OCTOBER. 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CONTENTS I Notes on Cibber's Plays II Cibber and the Development of Sentimental Comedy Bibliography PREFACE The following studies are extracts from a longer paper on the life and work of Cibber. No extended investigation concerning the life or the literary activity of Cibber has recently appeared, and certain misconceptions concerning his personal character, as well as his importance in the development of English literature and the literary merit of his plays, have been becoming more and more firmly fixed in the minds of students. Cibber was neither so much of a fool nor so great a knave as is generally supposed. The estimate and the judgment of two of his contemporaries, Pope and Dennis, have been far too widely accepted. The only one of the above topics that this paper deals with, otherwise than incidentally, is his place in the development of a literary mode. While Cibber was the most prominent and influential of the innovators among the writers of comedy of his time, he was not the only one who indicated the change toward sentimental comedy in his work. This subject, too, needs fuller investigation. I hope, at some future time, to continue my studies in this field. This work was suggested as a subject for a doctor's thesis, by Professor John Matthews Manly, while I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago a number of years ago, and was con• tinued later under the direction of Professor Thomas Marc Par- rott at Princeton. -

I the POLITICS of DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS

THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 by Loring Pfeiffer B. A., Swarthmore College, 2002 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Loring Pfeiffer It was defended on May 1, 2015 and approved by Kristina Straub, Professor, English, Carnegie Mellon University John Twyning, Professor, English, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, Courtney Weikle-Mills, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Loring Pfeiffer 2015 iii THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 Loring Pfeiffer, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The Politics of Desire argues that late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women playwrights make key interventions into period politics through comedic representations of sexualized female characters. During the Restoration and the early eighteenth century in England, partisan goings-on were repeatedly refracted through the prism of female sexuality. Charles II asserted his right to the throne by hanging portraits of his courtesans at Whitehall, while Whigs avoided blame for the volatility of the early eighteenth-century stock market by foisting fault for financial instability onto female gamblers. The discourses of sexuality and politics were imbricated in the texts of this period; however, scholars have not fully appreciated how female dramatists’ treatment of desiring female characters reflects their partisan investments. -

Moral Intent in the Plays and Dramatic Criticism of Richard Steele

Moral intent in the plays and dramatic criticism of Richard Steele Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Feldman, Donna Rose, 1925- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 01:14:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318914 MORAL INTENT IN THE PLAYS AND DRAMATIC CRITICISM OF RICHARD STEELE by Donna Feldman A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 19^8 Approved» - Director of Thesis mm SiVsoO- TABLE OF COUTEiTS CHAPTER,: ' ■ : . ■ ; : : ; ' PAGE ' lo. IITRQDHCTIOI . , . = . = . o'-.o . 1 : II. EIGLISH DRAMA TO THE TIME OP STEELE, 8 III. STEELE'S EARLY PLAYS o o o o o o o o o 31 Introduction to the Study 31 The Funeral o o o o o o 0 o o d „o/ e 32 : Plot synopsis.' , o o o o <y o o o 32 Theme,o » o o o o o o o o o o o o o 3% Moral intent . » . .. N-0 o o o o o hh General effectiveness.>0.0 P o o O hS The Lying Lover' O O 0,00 O O 6 46 Plot synopsis. O .O 9 0 o o o o > ? Tlfe^ie. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

The Rover by Aphra Behn

By Shailesh Ranjan Assistant Professor Dept. of English, Maharaja College, Ara. About the Author Aphra Behn was one of the first English professional writers wrote plays, poetry, short stories and novels. Little information is known about her early life. She was born in about 1640 near Canterbury, England.Her family were Royalists, connected with powerful catholic families and the court. She may have been raised Catholic and educated in a convent abroad. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barriers and served as a literary role model for later generations of women authors. Rising from obscurity, she came to the notice of Charles II , who employed her as a spy in Antwerp. •After her return to London she started her writings. •She wrote under the pastrol pseudonym Astrea. •A staunch supporter of the Stuart Line, she declined an invitation from Bishop Burnet to write a welcoming poem to the new king William III. •She died shortly after. Her grave is not included in the Poets Corner but lies in the East Cloister near the steps to the church. •Virginia Woolf writes about her in her famous work ‘A Room of One’s Own’ - “ All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn which is , most scandalously but rather appropriately, in Westminster Abbey, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.” • She challenged with expressing herself in a patriarchal system that generally refused to grant merit to women’s views.Women who went against were in risk of being exiled from their communities and targeted to be involved in witch hunts. -

Mask, Mirror, and Weapon:Pope's Versatile Satire

Grant 1 Mask, Mirror, and Weapon: Pope’s Versatile Satire Nina Grant The history and life of a writer are often a monumental influence on their works and opinions. Alexander Pope is no exception, and he had a great deal of experience to draw from. Pope was a person closely acquainted with hardship from a multitude of sources, including reli- gious discrimination, harsh critiques of his writing, and an extreme physical disability. Instead of dwelling on miserable events and pouring his suffering into his work emotionally, Pope uses his poetry to correct the prejudice thrown his way through calculated vocabulary choices and direct analogies of those for whom he had ample distaste. Pope elevates his most desirable qualities while simultaneously criticizing and pushing down his rivals and enemies, all under the cover of satire and fiction. Through his writing, Pope reverses the multitude of prejudices that he has ex- perienced through judgement of his faith, his writing, and his physicality, both to preserve his dignity and status as well as to pursue the contentedness that he was never able to obtain. From a young age, Pope endured a physical disability that left him at under five feet in height. This is something that was clearly a struggle for him both as a label and a physical com- plication, because he experienced several severe health conditions as a result (Deutsch 2). He also expressed his pain, both physical and emotional, in several letters to the close people in his life. Damrosch examines these correspondences with special attention to one addressed to Bath- urst, in which Pope lamentingly describes his body as a burden to himself and others, claiming it is as useless as dead weight (21). -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOCIAL CRITICISM in the ENGLISH NOVEL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-8810 CLEMENTS, Frances Marion, 1927- SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE ENGLISH NOVEL: 1740-1754. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE ENGLISH NOVEL 1740- 175^ DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Frances Marion Clements, B.A., M.A. * # * * # * The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by (L_Lji.b A< i W L _ Adviser Department of English ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the Library of Congress and the Folger Shakespeare Library for allowing me to use their resources. I also owe a large debt to the Newberry Library, the State Library of Ohio and the university libraries of Yale, Miami of Ohio, Ohio Wesleyan, Chicago, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Wisconsin for their generosity in lending books. Their willingness to entrust precious eighteenth-century volumes to the postal service greatly facilitated my research. My largest debt, however, is to my adviser, Professor Richard D. Altick, who placed his extensive knowledge of British social history and of the British novel at my disposal, and who patiently read my manuscript more times than either of us likes to remember. Both his criticism and his praise were indispensable. VITA October 17, 1927 Born - Lynchburg, Virginia 1950 .......... A. B., Randolph-Macon Women's College, Lynchburg, Virginia 1950-1959• • • • United States Foreign Service 1962-1967. • • • Teaching Assistant, Department of English, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1962 ..... -

Drama Co- Productions at the BBC and the Trade Relationship with America from the 1970S to the 1990S

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co- productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/56/ Version: Full Version Citation: Das Neves, Sheron Helena Martins (2013) ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co-productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s. MPhil thesis, Birkbeck, University of Lon- don. c 2013 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email BIRKBECK, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND SCREEN MEDIA MPHIL VISUAL ARTS AND MEDIA ‘RUNNING A BROTHEL FROM INSIDE A MONASTERY’: DRAMA CO-PRODUCTIONS AT THE BBC AND THE TRADE RELATIONSHIP WITH AMERICA FROM THE 1970s TO THE 1990s SHERON HELENA MARTINS DAS NEVES I hereby declare that this is my own original work. August 2013 ABSTRACT From the late 1970s on, as competition intensified, British broadcasters searched for new ways to cover the escalating budgets for top-end drama. A common industry practice, overseas co-productions seems the fitting answer for most broadcasters; for the BBC, however, creating programmes that appeal to both national and international markets could mean being in conflict with its public service ethos. Paradoxes will always be at the heart of an institution that, while pressured to be profitable, also carries a deep-rooted disapproval of commercialism. -

Print This Article

JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES – VOLUME 17 (2019), 127-147. http://doi.org/10.18172/jes.3565 “DWINDLING DOWN TO FARCE”?: APHRA BEHN’S APPROACH TO FARCE IN THE LATE 1670S AND 80S JORGE FIGUEROA DORREGO1 Universidade de Vigo [email protected] ABSTRACT. In spite of her criticism against farce in the paratexts of The Emperor of the Moon (1687), Aphra Behn makes an extensive use of farcical elements not only in that play and The False Count (1681), which are actually described as farces in their title pages, but also in Sir Patient Fancy (1678), The Feign’d Curtizans (1679), and The Second Part of The Rover (1681). This article contends that Behn adapts French farce and Italian commedia dell’arte to the English Restoration stage mostly resorting to deception farce in order to trick old husbands or fathers, or else foolish, hypocritical coxcombs, and displaying an impressive, skilful use of disguise and impersonation. Behn also turns widely to physical comedy, which is described in detail in stage directions. She appropriates farce in an attempt to please the audience, but also in the service of her own interests as a Tory woman writer. Keywords: Aphra Behn, farce, commedia dell’arte, Restoration England, deception, physical comedy. 1 The author wishes to acknowledge funding for his research from the Spanish government (MINECO project ref. FFI2015-68376-P), the Junta de Andalucía (project ref. P11-HUM-7761) and the Xunta de Galicia (Rede de Lingua e Literatura Inglesa e Identidade III, ref. ED431D2017/17). 127 Journal of English Studies, vol. 17 (2019) 127-147 Jorge Figueroa DORREGO “DWINDLING DOWN TO FARCE”?: LA APROXIMACIÓN DE APHRA BEHN A LA FARSA EN LAS DÉCADAS DE 1670 Y 1680 RESUMEN.