Charnel Practices in Medieval England: New Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of George Wymant

Descendants of George Wymant Generation 1 1. GEORGE1 WYMANT . He met ANN. George Wymant and Ann had the following child: 2. i. GEORGE2 WIMAN was born on 15 Nov 1657 in Arthingworth, Northamptonshire, England. He married Elizabeth Philip on 22 Oct 1676 in Kettering, Northants. Generation 2 2. GEORGE2 WIMAN (George1 Wymant) was born on 15 Nov 1657 in Arthingworth, Northamptonshire, England. He married Elizabeth Philip on 22 Oct 1676 in Kettering, Northants. George Wiman and Elizabeth Philip had the following child: 3. i. JOHN3 WYMAN was born about 1677 in Kettering, Northants. He died on 01 Sep 1749 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. He married Elizabeth Curtis on 21 Feb 1699 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. Generation 3 3. JOHN3 WYMAN (George2 Wiman, George1 Wymant) was born about 1677 in Kettering, Northants. He died on 01 Sep 1749 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. He married Elizabeth Curtis on 21 Feb 1699 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. John Wyman and Elizabeth Curtis had the following children: i. MARY4 WYMAN was born in 1700 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. ii. JOHN WYMAN was born on 05 Sep 1703 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. He married Katherine Smith on 24 Sep 1727 in Stamford. 4. iii. ROBERT WYMAN was born in 1706 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. He died about May 1784 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. He married Anne Brown, daughter of John Brown and Mary Appleby, on 09 Oct 1732 in Thorpe Achurch, Northamptonshire, England. She was born in 1710 in Thorpe Achurch, Northamptonshire, England. iv. MATTHEW WYMAN was born in 1709 in Harringworth, Northamptonshire, England. He died about 1750. -

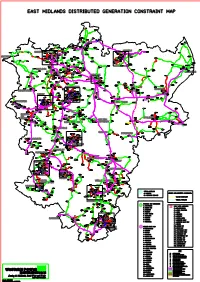

East Midlands Constraint Map-Default

EAST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP MISSON MISTERTON DANESHILL GENERATION NORTH WHEATLEY RETFOR ROAD SOLAR WEST GEN LOW FARM AD E BURTON MOAT HV FARM SOLAR DB TRUSTHORPE FARM TILN SOLAR GENERATION BAMBERS HALLCROFT FARM WIND RD GEN HVB HALFWAY RETFORD WORKSOP 1 HOLME CARR WEST WALKERS 33/11KV 33/11KV 29 ORDSALL RD WOOD SOLAR WESTHORPE FARM WEST END WORKSOPHVA FARM SOLAR KILTON RD CHECKERHOUSE GEN ECKINGTON LITTLE WOODBECK DB MORTON WRAGBY F16 F17 MANTON SOLAR FARM THE BRECK LINCOLN SOLAR FARM HATTON GAS CLOWNE CRAGGS SOUTH COMPRESSOR STAVELEY LANE CARLTON BUXTON EYAM CHESTERFIELD ALFORD WORKS WHITWELL NORTH SHEEPBRIDGE LEVERTON GREETWELL STAVELEY BATTERY SW STN 26ERIN STORAGE FISKERTON SOLAR ROAD BEVERCOTES ANDERSON FARM OXCROFT LANE 33KV CY SOLAR 23 LINCOLN SHEFFIELD ARKWRIGHT FARM 2 ROAD SOLAR CHAPEL ST ROBIN HOOD HX LINCOLN LEONARDS F20 WELBECK AX MAIN FISKERTON BUXTON SOLAR FARM RUSTON & LINCOLN LINCOLN BOLSOVER HORNSBY LOCAL MAIN NO4 QUEENS PARK 24 MOOR QUARY THORESBY TUXFORD 33/6.6KV LINCOLN BOLSOVER NO2 HORNCASTLE SOLAR WELBECK SOLAR FARM S/STN GOITSIDE ROBERT HYDE LODGE COLLERY BEEVOR SOLAR GEN STREET LINCOLN FARM MAIN NO1 SOLAR BUDBY DODDINGTON FLAGG CHESTERFIELD WALTON PARK WARSOP ROOKERY HINDLOW BAKEWELL COBB FARM LANE LINCOLN F15 SOLAR FARM EFW WINGERWORTH PAVING GRASSMOOR THORESBY ACREAGE WAY INGOLDMELLS SHIREBROOK LANE PC OLLERTON NORTH HYKEHAM BRANSTON SOUTH CS 16 SOLAR FARM SPILSBY MIDDLEMARSH WADDINGTON LITTLEWOOD SWINDERBY 33/11 KV BIWATER FARM PV CT CROFT END CLIPSTONE CARLTON ON SOLAR FARM TRENT WARTH -

Holy Trinity Church

Holy Trinity Church Ingham - Norfolk HOLY TRINITY CHURCH INGHAM Ingham, written as “Hincham” in the Domesday Book, means “seated in a meadow”. Nothing of this period survives in the church, the oldest part of which now seems the stretch of walling at the south west corner of the chancel. This is made of whole flints, as against the knapped flint of the rest of the building, and contains traces of a blocked priest’s doorway. In spite of the herringboning of some of the rows of flints, it is probably not older than the thirteenth century. The rest of the body of the church was rebuilt in the years leading up to 1360.Work would have started with the chancel, but it is uncertain when it was begun. The tomb of Sir Oliver de Ingham, who died in 1343, is in the founder’s position on the north side of the chancel, and since the posture of the effigy is, as we shall see, already old fashioned for the date of death, it seems most likely that it was commissioned during his life time and that he rebuilt the chancel (which is Pevsner’s view), or that work began immediately after his death by his daughter Joan and her husband, Sir Miles Stapleton, who also rebuilt the nave. The Stapletons established a College of Friars of the Order of Holy Trinity and St Victor to serve Ingham, and also Walcot. The friars were installed in 1360, and originally consisted of a prior, a sacrist, who also acted as vicar of the parish, and two more brethren. -

192 Finedon Road Irthlingborough | Wellingborough

192 Finedon Road Irthlingborough | Wellingborough | Northamptonshire | NN9 5UB 192 FINEDON ROAD A beautifully presented detached family house with integral double garage set in half an acre located on the outskirts of Irthlingborough. The house is set well back from the road and is very private with high screen hedging all around, it is approached through double gates to a long gravelled driveway with beautifully maintained mature gardens to the side and rear, there is ample parking to the front leading to the garage. Internally the house has a flexible layout and is arranged over three floors with scope if required to create a separate guest annexe. On entering you immediately appreciate the feeling of light and space; there is a bright entrance hall with wide stairs to the upper and lower floors. On the right is a study and the large reception room which opens to the conservatory with access to a sun terrace, the conservatory leads through to a further conservatory currently used as a dining room. To the rear of the house is a family kitchen breakfast room which also opens to the conservatory/dining room. On the upper floor are the bedrooms, the master bedroom is a great size with a dressing area and an en-suite shower room. There are a further two double bedrooms and a smart family bathroom. On the lower floor is a good size utility room and a further double bedroom which opens to the large decked terrace and garden, there is also a further shower room and a separate guest cloakroom. -

"Wherein Taylors May Finde out New Fashions"1

"Wherein Taylors may finde out new fashions"1 Constructing the Costume Research Image Library (CRIL) Dr Jane Malcolm-Davies Textile Conservation Centre, Winchester School of Art 1) Introduction The precise construction of 16th century dress in the British Isles remains something of a conundrum although there are clues to be found in contemporary evidence. Primary sources for the period fall into three main categories: pictorial (art works of the appropriate period), documentary (written works of the period such as wardrobe warrants, personal inventories, personal letters and financial accounts), and archaeological (extant garments in museum collections). Each has their limitations. These three sources provide a fragmentary picture of the garments worn by men and women in the 16th century. There is a need for further sources of evidence to add to the partial record of dress currently available to scholars and, increasingly, those who wish to reconstruct dress for display or wear, particularly for educational purposes. The need for accessible and accurate information on Tudor dress is therefore urgent. Sources which shed new light on the construction of historic dress and provide a comparison or contrast with extant research are invaluable. This paper reports a pilot project which attempted to link the dead, their dress and their documents to create a visual research resource for 16th century costume. 2) The research problem There is a fourth primary source of information that has considerable potential but as yet has been largely overlooked by costume historians. Church effigies are frequently life-size, detailed and dressed in contemporary clothes. They offer a further advantage in the portrayal of many middle class who do not appear in 1 pictorial sources in as great a number as aristocrats. -

08/09/2018 St Neots Mens Own 15:00:00 08/09/2018 Bletchley Northampton Old Scouts 15:00:00 08/09/2018 Bugbrooke Northampton Casu

08/09/2018 St Neots Mens Own 15:00:00 08/09/2018 Bletchley Northampton Old Scouts 15:00:00 08/09/2018 Bugbrooke Northampton Casuals 15:00:00 08/09/2018 Long Buckby Northampton BBOB 15:00:00 08/09/2018 Oundle no fixture 15:00:00 15/09/2018 Northampton BBOB Bugbrooke 15:00:00 15/09/2018 Northampton Casuals Bletchley 15:00:00 15/09/2018 Northampton Old Scouts St Neots 15:00:00 15/09/2018 Mens Own Oundle 15:00:00 15/09/2018 Long Buckby no fixture 15:00:00 22/09/2018 Bletchley Oundle 15:00:00 22/09/2018 Bugbrooke Mens Own 15:00:00 22/09/2018 Long Buckby Northampton Old Scouts 15:00:00 22/09/2018 Northampton BBOB Northampton Casuals 15:00:00 22/09/2018 St Neots no fixture 15:00:00 03/11/2018 Northampton Casuals Long Buckby 15:00:00 03/11/2018 Northampton Old Scouts Bugbrooke 15:00:00 03/11/2018 Mens Own Bletchley 15:00:00 03/11/2018 Oundle St Neots 15:00:00 03/11/2018 Northampton BBOB no fixture 15:00:00 24/11/2018 Bugbrooke St Neots 15:00:00 24/11/2018 Long Buckby Oundle 15:00:00 24/11/2018 Northampton BBOB Mens Own 15:00:00 24/11/2018 Northampton Casuals Northampton Old Scouts 15:00:00 24/11/2018 Bletchley no fixture 15:00:00 12/01/2019 Northampton Old Scouts Northampton BBOB 15:00:00 12/01/2019 Mens Own Long Buckby 15:00:00 12/01/2019 Oundle Bugbrooke 15:00:00 12/01/2019 St Neots Bletchley 15:00:00 12/01/2019 Northampton Casuals no fixture 15:00:00 26/01/2019 Long Buckby Bletchley 15:00:00 26/01/2019 Northampton BBOB St Neots 15:00:00 26/01/2019 Northampton Casuals Oundle 15:00:00 26/01/2019 Northampton Old Scouts Mens Own 15:00:00 26/01/2019 -

Oundle Church of England Primary School Enrichment and Extra-Curricular Sport and Physical Activity

Oundle Church of England Primary School Enrichment and Extra-Curricular Sport and Physical Activity Since the introduction of the sports premium we have greatly increased our participation in competitive activities across all levels of the school games. This increase has seen a wider range and increased number of pupils engaged in sport and physical activity throughout the year. School Games 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 Level 1 3 6 9 11 15 2 6 8 9 15 23 3 0 1 1 4 2 4 0 0 0 0 0 B Teams 3 4 2 7 12 C Teams 1 2 1 2 4 Participation in Competitive Sport since London 2012 Level 1: Intra School; Level 2: Inter-School; Level 3: County; Level 4: Regional/National competition Increased participation has had an impact on our school and our pupils beyond winning however. Our pupils are more engaged in class, display incredible sportsmanship, compassion and teamwork on and off the field, as well being healthier physically and emotionally. Additional programmes for pupils less inclined towards competitive sport on offer at Oundle Primary School include yoga, mindfulness, change 4 life sports clubs (Including Cookery and healthy Eating) and pupil leadership schemes. We are in regular contact with our local partners at Northamptonshire Sport to continue developing our provision, as well as working with colleagues at local amateur and professional sports clubs to ensure a high quality provision in as many sports as possible. We have also used our relationships to inspire our pupils through visits to Peterborough United (Y2) and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (Y4). -

Newsletter September 2011 Contents

PETERBOROUGH DIOCESAN GUILD OF CHURCH BELLRINGERS Newsletter September 2011 contents The President’s Piece 03 From The Master 04 News from the Branches Culworth 05 Daventry 07 Guilsborough 13 Kettering 14 Northampton 17 Peterborough 20 Rutland 26 Thrapston 27 Towcester 27 Wellingborough 28 Public Relations Officer’s Piece 30 100 Club 31 Guild Spring Meeting 31 AGM 33 Other News and Events 34 Guild Website 42 Guild Events 2009 43 It’s nice to see reports from so many contributors this time. Please keep this going by keeping notes of activities in your branch. The deadline for the next Newsletter is :28th February 2012 Please make a note of this date in your diary Please send your contribution either through your Branch Press Correspondent or direct to : e-mail : [email protected] or Tel : 01536 420822 the president’s piece Hello everyone, I hope you have had an enjoyable holiday with good ringing whether at home, on outings or on a ringing weekend or holiday. I went on a very good holiday to the vale of Glamorgan, an area I have never been to before, which had some interesting bells and churches and very varied scenery. Back to Easter Saturday and the sponsored walk and cycle ride. It was a beautiful warm sunny day with about 40 people walking and cycling. The cyclists went round Rutland Water with or without the peninsular and the walkers walked round the peninsular. The best part of the walk was the bluebell woods and at one place a whole field full of them. After we had finished the walk we met the cyclists at the Pub at Manton which was packed inside and out with everyone enjoying the lovely weather. -

G.F. Nuttall, "The State of Religion in Northamptonshire (1793) by Andrew Fuller,"

177 THE STATE OF RELIGION IN NORTHAMPTONSHIRE (1793) BY ANDREW FULLER The letter fr'om Andrew Fuller transcr ibed below is preserved in the Congregational Library, London (Box H d 9). With other documents, it appears to be part of the response to an inquiry concerning the state of religion in England and .Wales which the Board of Managers of the Evangelical Magazine instituted when the Magazine was established in 1793. The "Heads of EnqQiry" were approved and transcribed in their first Minute Book, which in 1974 came into the possession of the Library of the United Reformed Church History Society in London. John Eyre was given the title of "Final Editor". I have not succeeded in identifying Fuller's correspondent, Josiah Lewis. A copy of John Gill's The Watchman's Answer to the Question, What of the Night? (1792) is preserved in the Congregational Library, which was given to Lewis on 16th July 1801 by Dan Taylor, so possibly Lewis was a General Baptist of the New Connexion, and a layman. The names of the six forerunners to whose labours Fuller looks back with gratitude make an interesting list. Hervey, Doddridge, Ryland and Maurice are still remembered; Abraham Maddock was Thomas Jones' predecessor as curate-in-charge of Great Creaton; William Grant was pastor of the Independent church worshipping at West End, Wellihgborough. In square brackets I have inserted a number of Christian names, the Baptist names from the lists printed in the first two volumes of the Baptist Annual Register, the Independent from T. Coleman's Memorials of the Independent Churches in Northamptonshire (1853). -

NORTHAMPTONSHIRE. [ KELLY's Higgins Mrs

346 BIG NORTHAMPTONSHIRE. [ KELLY'S Higgins Mrs. The Cedars, Dogs- Holdich Rev. Charles WaIter M.A. Horn Joseph, Holmefield ho. IrthIing- thorpe, Peterborough Vicarage, Werrington, Peterborough boro', Higham Ferrers RS.O Higgins Mrs. WaIter B. Sibley house, Holdich F. White, Fengate house, Fen- Horn Miss, Wharf rd. Long Buckby, Long Buckby, Rugby gate, Peterborough Rugby Riggins 'l'.9Victoria prmnde.Nthmptn Holdich Harry, Winifred villa, Thorpe Hornby Frederick, 6 The Crescent, Higgins Thomas Henry, Rockcliffe, Lea road, Peterborough Phippsville, Northampton ~Iidland road, Wellingborough Holdich J. 273 Eastfield rd. Peterboro' Hornby Mrs. 3 St. George's place, Higgs Rev. Edward Hood,The Laurels, Holdich Mrs. Lillian villa, Granville Leicester road, Northampton O"erthorpe, Banbury street, Peterborough Hornby Mrs. The Grange, Earls Bar- Hi~s G. The Lawn, ""Vothorpe,Stmfrd Holdich T. 172 Lincoln rd. Peterboro' ton, Northampton Higgs ~Irs. 128 Abington av.Nrthmptn Holdich T. W. 34 Westgate, Peterboro' Horne 001. Henry, Priestwell house, Higgs William, 5 Birchfield rd.Phipps- Holdich W. 271 Eastfield rd.Peterboro' East Haddon, Northampton ville, Northampton Holding Rev. W., L.Th. Moulton, Bornsby James D.L., J.P. Laxton pk. Higgs Wm. 73 CoHvvn rd. Northamptn Northampton Stamford Higham William, High st. Towcester Holding Matthew Henry, 5 Spencer Hornsby Miss, YardIey Hastings, Hight ""Villiam, 26 Birchfield road, parade, Northampton Northampton Phippsville, Northampton Holiday John, Banksey villa, Wood- Hornsey Wm.36 Abington av.Kthmptn Hill Col. J., J.P. Wollaston hall, Wel- ford Halse, Byfield RS.O Hornstein J. G. Laxton house, Oundle lingborough Holland H.4 St.George's st.Northmptn Horrell Rev. Thomas H. 32 Watkin Hill Chas. -

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031 Regulation 19 consultation, February 2021 Contents Page Foreword 9 1.0 Introduction 11 2.0 Area Portrait 27 3.0 Vision and Outcomes 38 4.0 Spatial Development Strategy 46 EN1: Spatial development strategy EN2: Settlement boundary criteria – urban areas EN3: Settlement boundary criteria – freestanding villages EN4: Settlement boundary criteria – ribbon developments EN5: Development on the periphery of settlements and rural exceptions housing EN6: Replacement dwellings in the open countryside 5.0 Natural Capital – environment, Green Infrastructure, energy, 66 sport and recreation EN7: Green Infrastructure corridors EN8: The Greenway EN9: Designation of Local Green Space East Northamptonshire Council Page 1 of 225 East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2: Pre-Submission Draft (February 2021) EN10: Enhancement and provision of open space EN11: Enhancement and provision of sport and recreation facilities 6.0 Social Capital – design, culture, heritage, tourism, health 85 and wellbeing, community infrastructure EN12: Health and wellbeing EN13: Design of Buildings/ Extensions EN14: Designated Heritage Assets EN15: Non-Designated Heritage Assets EN16: Tourism, cultural developments and tourist accommodation EN17: Land south of Chelveston Road, Higham Ferrers 7.0 Economic Prosperity – employment, economy, town 105 centres/ retail EN18: Commercial space to support economic growth EN19: Protected Employment Areas EN20: Relocation and/ or expansion of existing businesses EN21: Town -

Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Revocation of the East

Appendix A – SEA of the Revocation of the East Midlands Regional Strategy Appendix A Policies in the East Midlands Regional Strategy This Appendix sets out the text of the policies that make up the Regional Strategy for the East Midlands. It comprises policies contained in The East Midlands Regional Plan published in March 2009. The East Midlands Regional Plan POLICY 1: Regional Core Objectives To secure the delivery of sustainable development within the East Midlands, all strategies, plans and programmes having a spatial impact should meet the following core objectives: a) To ensure that the existing housing stock and new affordable and market housing address need and extend choice in all communities in the region. b) To reduce social exclusion through: • the regeneration of disadvantaged areas, • the reduction of inequalities in the location and distribution of employment, housing, health and other community facilities and services, and by; • responding positively to the diverse needs of different communities. c) To protect and enhance the environmental quality of urban and rural settlements to make them safe, attractive, clean and crime free places to live, work and invest in, through promoting: • ‘green infrastructure’; • enhancement of the ‘urban fringe’; • involvement of Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships; and • high quality design which reflects local distinctiveness. d) To improve the health and mental, physical and spiritual well being of the Region's residents through improvements in: • air quality; • ‘affordable warmth’;