A Psychometrics of Individual Differences in Experimental Tasks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSU Department of Psychology First-Tier Journals List

OSU Department of Psychology First-Tier Journals List To search for a journal not listed here, visit the Journal Citation Reports website by clicking here FIRST TIER - GENERAL 2015 2015 Journal 2016 2016 Journal 2017 2017 Journal Impact Ranking Impact Ranking Impact Ranking Rating Rating Rating American Psychologist 5.454 10/129 (Psychology, 6.681 7/128 (Psychology, 4.856 9/135 (Psychology, Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Annual Review of Psychology 19.085 2/129 (Psychology, 19.950 1/128 (Psychology, 22.774 2/135 (Psychology, Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Psychological Bulletin 14.839 3/129 (Psychology, 16.793 2/128 (Psychology, 13.250 4/135 (Psychology, Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Psychological Methods 5.000 11/129 (Psychology, 4.667 10/128 (Psychology, 6.485 7/135 (Psychology, Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Psychological Review 7.581 5/129 (Psychology, 7.638 5/128 (Psychology, 7.230 6/135 (Psychology, Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Psychological Science 5.476 9/129 (Psychology, 5.667 8/128 (Psychology, 6.128 8/135 (Psychology, Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) Multidisciplinary) 2015 2015 Journal 2016 2016 Journal 2017 2017 Journal FIRST TIER SPECIALTY Impact Ranking Impact Ranking Impact Ranking Area Other Rating Rating Rating 3.268 9/51 (Behavioral 2.385 29/51 (Behavioral 2.036 34/51 (Behavioral Behavior Genetics Sciences) Sciences) Sciences) BN 3.048 3/13 (Psychology, 3.623 1/13 (Psychology, 3.597 -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology -

Experimental Psychology Programs Handbook

Experimental Psychology Programs Handbook Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology M.A. in Experimental Psychology Cognition & Cognitive Neuroscience Area Human Factors Area Social Psychology Area Edition: 2019-2020 Last Revision: 8/23/19 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Practical Issues ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Department & Program Structure ........................................................................................................... 2 Advisors .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Registration and Enrollment ................................................................................................................... 3 Performance Requirements .................................................................................................................... 3 Course Withdrawals ............................................................................................................................... 4 Second Year Project Timeline ................................................................................................................ 4 Recommended Timeline of Major Milestones ....................................................................................... -

Introduction to Psychology Historical Timeline Of

Kumar Hritwik E- Content material ANS College, Nabinagar Assistant Professor Psychology INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGY HISTORICAL TIMELINE OF MODERN PSYCHOLOGY AND HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY IN INDIA Prepared by: Kumar Hritwik Assistant Professor Department of Psychology ANS College, Nabinagar Magadh University, Bodh Gaya This e-content has been designed for the B.A. Part-I Psychology Students. This e-content must be read in continuation to the previously drafted content on Introduction to Psychology for better understanding. This E-content material designed by Kumar Hritwik is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. 1 Page Kumar Hritwik E- Content material ANS College, Nabinagar Assistant Professor Psychology Historical Timeline of Modern Psychology The timeline of Psychology spans centuries, with the earliest known mention of clinical depression in 1500 BCE on an ancient Egyptian manuscript known as the Ebers Papyrus. However, it was not until the 11th century that the Persian physician Avicenna attributed a connection between emotions and physical responses in a practice roughly dubbed "physiological psychology." Some consider the 17th and 18th centuries the birth of modern psychology (largely characterized by the publication of William Battie's "Treatise on Madness" in 1758). Others consider the mid- 19th century experiments done in Hermann von Helmholtz's lab to be the start of modern psychology. Many say that 1879, when Wilhelm Wundt established the first experimental psychology lab, was the true beginning of psychology as we know it. From that moment forward, the study of psychology would continue to evolve as it does today. Highlighting that transformation were a number of important, landmark events. -

Perception and Identification of Random Events

Journal of Experimental Psychology: © 2014 American Psychological Association Human Perception and Performance 0096-1523/14/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0036816 2014, Vol. 40, No. 4, 1358–1371 Perception and Identification of Random Events Jiaying Zhao Ulrike Hahn University of British Columbia Birkbeck College, University of London Daniel Osherson Princeton University The cognition of randomness consists of perceptual and conceptual components. One might be able to discriminate random from nonrandom stimuli, yet be unable to identify which is which. In a series of experiments, we compare the ability to distinguish random from nonrandom stimuli to the accuracy with which given stimuli are identified as “random.” In a further experiment, we also evaluate the encoding hypothesis according to which the tendency of a stimulus to be labeled random varies with the cognitive difficulty of encoding it (Falk & Konold, 1997). In our experiments, the ability to distinguish random from nonrandom stimuli is superior to the ability to correctly label them. Moreover, for at least 1 class of stimuli, difficulty of encoding fails to predict the probability of being labeled random, providing evidence against the encoding hypothesis. Keywords: randomness, perception, texture, alternation bias How people understand randomness has been a question of bling (e.g., Dreman, 1977; Ladouceur, Sylvain, Letarte, Giroux, & longstanding interest in psychology. The ability to apprehend Jacques, 1998; Manski, 2006; Michalczuk, Bowden-Jones, randomness is fundamental to cognition since it involves noticing Verdejo-Garcia, & Clark, 2011). Experience with randomness may structure, or the lack thereof, in the environment (Bar-Hillel & also influence religious beliefs (Kay, Moscovitch, & Laurin, Wagenaar, 1991). -

University of Rhode Island School Psychology Graduate Programs Adopted May 4, 2015

University of Rhode Island School Psychology Graduate Program Handbook Ph.D. Program in School Psychology 2017-2018 URI School Psychology Ph.D. Program Handbook, 2017-2018, p.2 Table of Contents 1. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 4 2. URI’S SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY PROGRAM................................................................................................... 5 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 MISSION .................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 PROGRAM PHILOSOPHY AND MODEL .................................................................................................................................. 6 PROGRAM EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY, GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND COMPETENCIES................................................... 7 Educational Philosophy ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Relationships between Program Goals, Curriculum Objectives, and Student Competencies ............... 8 MULTICULTURAL EMPHASIS .............................................................................................................................................. -

Experimental Psychology: Cognition and Decision Making PSYC UN1490 Preliminary Syllabus for Fall 2018 Course Information Points

Experimental Psychology: Cognition and Decision Making PSYC UN1490 Preliminary Syllabus for Fall 2018 Course Information Points: 4 Students must register for both UN1490 and one of the lab sections of UN1491. Lecture time: Monday 4:10-6pm Lecture location: 614 Schermerhorn Lab 1: Monday 6:10-8pm (200b Schermerhorn) Lab 2: Monday 6:10-8pm (200c Schermerhorn) Lab 3: Tuesday 4:10-6pm (200b Schermerhorn) Lab 4: Monday 8:10-10pm (200b Schermerhorn)* Lab 5: Tuesday 6:10-8pm (200b Schermerhorn)* *note: Lab sections 4 & 5 will not open until the others are full and TAs have been assigned Instructor Information Katherine Fox-Glassman Office: 314 Schermerhorn Fall Office Hours: TBD email: [email protected] TA Information Please check our Canvas homepage for the most updated list of TA contact info and office hours. Grad TAs: TBD Bulletin Description Introduces research methods employed in the study of the cognitive and social determinants of thinking and decision making. Students gain experience in the conduct of research, including: design of simple experiments; observation and preference elicitation techniques; the analysis of behavioral data, considerations of validity, reliability, and research ethics; and preparation of written and oral reports. Note: Fee: $70. Attendance at the first class is essential. Prerequisites • Science of Psychology (PSYC 1001) or Mind, Brain, & Behavior (PSYC 1010), or equivalent intro psych course.* • An introductory statistics course (e.g., PSYC 1610, or STAT 1001, 1111, or 1211).* • Students are not required to have taken PSYC 2235 (Thinking & Decision Making), but as we will draw many examples from the field of judgment and decision making, you will find advantages to having taken either PSYC 2235 or another 2000-level psychology lecture course that introduces related topic areas (e.g., PSYC 2220 or PSYC 2640). -

Psychology and Its History

2 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCING PSYCHOLOGY'S HISTORY • Distinguish between primary and secondary sources of historical information and describe the kinds of primary source information typically found by historians in archives • Explain how the process of doing history can produce some degree of confidence that truth has been attained PSYCHOLOGY AND ITS HISTORY One hundred is a nice round number and a one-hundredth anniversary is ample cause for celebration. In recent years, psychologists with a sense of history have celebrated often. The festivities began back in 1979, with the centennial of the founding of Wilhelm Wundt's laboratory at Leipzig, Germany. In 1992, the American Psychological Associ ation (APA) created a yearlong series of events to commemorate the centennial of its founding in G. Stanley Hall's study at Clark University on July 8, 1892. During the cen tennial year, historical articles appeared in all of the APA's journals and a special issue of American Psychologist focused on history; several books dealing with APA's history were commissioned (e.g., Evans, Sexton, & Cadwallader, 1992); regional conventions had historical themes; and the annual convention in Washington featured events ranging from the usual symposia and invited addresses on history to a fancy dress ball at Union Station featuring period (1892) costumes and a huge APA birthday cake. Interest in psychology's history has not been limited to centennial celebrations, of course. Histories of psychology were written soon after psychology itself appeared on the academic scene (e.g., Baldwin, 1913), and at least two of psychology's most famous books, E. G. -

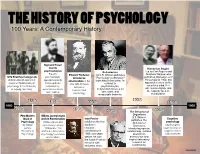

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

Experimental Psychology Program Sheet

EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY FPU BRINGS A TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE INTO THE EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY MINOR Experimental psychology is the scientific investigation of human behavior and thought through research studies using human participants. The Experimental Psychology minor prepares you to design and conduct robust human- participants research studies, following ethical guidelines and rules. You will frame your research questions, collect and analyze data, and write research manuscripts that share the results of your work. Studies may explore a wide variety of topics including cognition, memory, learning, neuroscience, social behavior, abnormal behavior, and human development issues. This program provides a strong foundation for graduate school in psychology or health-related fields. To earn the Experimental Psychology minor, you must complete a 24-credit course of study. 40 University Drive, Rindge, NH 03461 | (800) 437-0048 | franklinpierce.edu/experimentalpsych EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY ADVANTAGES OF AN EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY MINOR Experimental psychologists use scientific methods to collect data and perform research. They can work in varied settings, including universities, research centers, government and business. The Experimental Psychology minor is a good option for anyone considering graduate school, especially if you plan to pursue a Ph.D. in psychology or health- related fields. This minor will teach you how to do many of the human-participants research studies that will be conducted in graduate school. Undergraduate experience -

Goals Psychometric Theory: Goals II 4

Psychometric Theory • ‘The character which shapes our conduct is Psychology 405: a definite and durable ‘something’, and Psychometric Theory therefore! ... it is reasonable to attempt to measure it. (Galton, 1884) William Revelle • “Whatever exists at all exists in some amount. To know it thoroughly involves knowing its Northwestern University quantity as well as its!quality” (E.L. Thorndike, 1918) Spring, 2003 http://pmc.psych.nwu.edu/revelle/syllabi/405.html Psychometric Theory: Goals Psychometric Theory: Goals II 4. To instill an appreciation of and an interest 1. To acquire the fundamental vocabulary and in the principles and methods of logic of psychometric theory. psychometric theory. 2. To develop your capacity for critical 5. This course is not designed to make you judgment of the adequacy of measures into an accomplished psychometist (one purported to assess psychological constructs. who gives tests) nor is it designed to make 3. To acquaint you with some of the relevant you a skilled psychometrician (one who literature in personality assessment, constructs tests), nor will it give you "hands psychometric theory and practice, and on" experience with psychometric methods of observing and measuring affect, computer programs. behavior, cognition and motivation. Psychometric Theory: Text and Syllabus Requirements • Objective Midterm exam • Nunnally, Jum & Bernstein, Ira (1994) • Objective Final exam Psychometric Theory New York: • Final paper applying principles from the McGraw Hill, 3rd ed.(required: available course to a problem of interest to you. at Norris) • Sporadic applied homework and data sets • Loehlin, John (1998) Latent Variable Models: an introduction to factor, path, and structural analysis . Hillsdale, N.J.: LEA. -

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General Washing Away Your (Good or Bad) Luck: Physical Cleansing Affects Risk-Taking Behavior Alison Jing Xu, Rami Zwick, and Norbert Schwarz Online First Publication, June 27, 2011. doi: 10.1037/a0023997 CITATION Xu, A. J., Zwick, R., & Schwarz, N. (2011, June 27). Washing Away Your (Good or Bad) Luck: Physical Cleansing Affects Risk-Taking Behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0023997 Journal of Experimental Psychology: General © 2011 American Psychological Association 2011, Vol. ●●, No. ●, 000–000 0096-3445/11/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0023997 BRIEF REPORT Washing Away Your (Good or Bad) Luck: Physical Cleansing Affects Risk-Taking Behavior Alison Jing Xu Rami Zwick University of Toronto University of California, Riverside Norbert Schwarz University of Michigan Many superstitious practices entail the belief that good or bad luck can be “washed away.” Consistent with this belief, participants who recalled (Experiment 1) or experienced (Experiment 2) an episode of bad luck were more willing to take risk after having as opposed to not having washed their hands, whereas participants who recalled or experienced an episode of good luck were less willing to take risk after having as opposed to not having washed their hands. Thus, the psychological effects of physical cleansings extend beyond the domain of moral judgment and are independent of people’s motivation: incidental washing not only removes undesirable traces of the past (such as bad luck) but also desirable ones (such as good luck), which people would rather preserve. Keywords: Embodiment, superstition, risk taking, washing, sympathetic magic Superstitious attempts to control one’s luck often follow the inants, such as open wounds or spoiled food.