The Annual of the British School at Athens the Tsakonian Dialect.—I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KARYES Lakonia

KARYES Lakonia The Caryatides Monument full of snow News Bulletin Number 20 Spring 2019 KARYATES ASSOCIATION: THE ANNUAL “PITA” DANCE THE BULLETIN’S SPECIAL FEATURES The 2019 Association’s Annual Dance was successfully organized. One more time many compartiots not only from Athens, but also from other CONTINUE cities and towns of Greece gathered together. On Sunday February 10th Karyates enjoyed a tasteful meal and danced at the “CAPETANIOS” hall. Following the positive response that our The Sparta mayor mr Evagellos first special publication of the history of Valliotis was also present and Education in Karyes had in our previous he addressed to the Karyates issue, this issue continues the series of congratulating the Association tributes to the history of our country. for its efforts. On the occasion of the Greek National After that, the president of the Independence Day on March 25th, we Association mr Michael publish a new tribute to the Repoulis welcome all the participation of Arachovitians/Karyates compatriots and present a brief in the struggle of the Greek Nation to report for the year 2018 and win its freedom from the Ottoman the new year’s action plan. slavery. The board members of the Karyates Association Mr. Valliotis, Sparta Mayor At the same time, with the help of Mr. The Vice President of the Association Ms Annita Gleka-Prekezes presented her new book “20th Century Stories, Traditions, Narratives from the Theodoros Mentis, we publish a second villages of Northern Lacedaemon” mentioning that all the revenues from its sells will contribute for the Association’s actions. special reference to the Karyes Dance Group. -

Νέες Προσεγγίσεις Στην Αποκατάσταση Δασών Μαύρης Πεύκης» Σπάρτη, 15-16 Οκτωβρίου 2009

ΠΡΑΚΤΙΚΑ Διεθνές Συνέδριο «Νέες προσεγγίσεις στην αποκατάσταση δασών μαύρης πεύκης» Σπάρτη, 15-16 Οκτωβρίου 2009 PROCEEDINGS International Conference "New approaches to the restoration of black pine forests" Sparti, 15 - 16 October 2009 EPrO: LIFE07 NAT/GR/00286 NATURA 2 0 0 0 ΠΡΑΚΤΙΚΑ Διεθνές Συνέδριο «Νέες προσεγγίσεις στην αποκατάσταση δασών* "» Α μαύρηςΛ πευκης»Λ Σπάρτη, 15-16 Οκτωβρίου 2009 PROCEEDINGS International Conference "New approaches to the restoration of black pine forests" Sparti, 15 - 16 October 2009 Η παρούσα έκδοση έγινε στο πλαίσιο του έργου Life07 NAT/GR/000286 «Αποκατάσταση των δασών Pinus nigra στον Πάρνωνα (GR2520006) μέσω μίας δομημένης προσέγγισης» (www.parnonaslife.gr) που υλοποιείται από το Ελληνικό Κέντρο Βιοτόπων - Υγροτόπων (Δικαιούχος), την Περιφέρεια Πε- λοποννήσου, τον Φορέα Διαχείρισης Όρους Πάρνωνα και Υγροτόπου Μουστου και την Περιφέρεια Ανατολικής Μακεδονίας και Θράκης (Εταίροι). To έργο χρηματοδοτείται από τη ΓΔ Περιβάλλον της Ευρωπαϊκής Επιτροπής, τη Γενική Διευθυνση Ανάπτυξης και Προστασίας Δασών και Φυσικου Περι βάλλοντος, τον Δικαιούχο και τους Εταίρους. The present publication has been prepared in the framework of the Life07 NAT/GR/000286 «Restoration of Pinus nigra forests on Mount Parnonas (GR2520006) through a structured approach» (www.parnonaslife.gr) which is implemented by the Greek Biotope - Wetland Centre (Coordinating Beneficiary), the Region of Peloponnisos, the Management Body of mount Parnonas and Moustos wetland and the Region of Eastern Macedonia - Thrace (Associated Beneficiaries). -

Diplopoda) of Twelve Caves in Western Mecsek, Southwest Hungary

Opusc. Zool. Budapest, 2013, 44(2): 99–106 Millipedes (Diplopoda) of twelve caves in Western Mecsek, Southwest Hungary D. ANGYAL & Z. KORSÓS Dorottya Angyal and Dr. Zoltán Korsós, Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-1088 Budapest, Baross u. 13., E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Twelve caves of Western Mecsek, Southwest Hungary were examined between September 2010 and April 2013 from the millipede (Diplopoda) faunistical point of view. Ten species were found in eight caves, which consisted eutroglophile and troglobiont elements as well. The cave with the most diverse fauna was the Törökpince Sinkhole, while the two previously also investigated caves, the Abaligeti Cave and the Mánfai-kőlyuk Cave provided less species, which could be related to their advanced touristic and industrial utilization. Keywords. Diplopoda, Mecsek Mts., caves, faunistics INTRODUCTION proved to be rather widespread in the karstic regions of the former Yugoslavia (Mršić 1998, lthough more than 220 caves are known 1994, Ćurčić & Makarov 1998), the species was A from the Mecsek Mts., our knowledge on the not yet found in other Hungarian caves. invertebrate fauna of the caves in the region is rather poor. Only two caves, the Abaligeti Cave All the six millipede species of the Mánfai- and the Mánfai-kőlyuk Cave have previously been kőlyuk Cave (Polyxenus lagurus (Linnaeus, examined in speleozoological studies which in- 1758), Glomeris hexasticha Brandt, 1833, Hap- cludeed the investigation of the diplopod fauna as loporatia sp., Polydesmus collaris C. L. Koch, well (Bokor 1924, Verhoeff 1928, Gebhardt 1847, Ommatoiulus sabulosus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Leptoiulus sp.) were found in the entrance 1933a, 1933b, 1934, 1963, 1966, Farkas 1957). -

VENETIANS and OTTOMANS in the SOUTHEAST PELOPONNESE (15Th-18Th Century)

VENETIANS AND OTTOMANS IN THE SOUTHEAST PELOPONNESE (15th-18th century) Evangelia Balta* The study gives an insight into the historical and economic geography of the Southeast Peloponnese frorm the mid- fifteenth century until the morrow of the second Ottoma ill conquest in 1715. It necessarily covers also the period of Venetialll rule, whiciL was the intermezzo between the first and second perio.ds of Ottoman rule. By utilizing the data of an Ottoman archivrul material, I try to compose, as far as possible, the picture ())f that part of the Peloponnese occupied by Mount Pamon, which begins to t he south of the District of Mantineia, extends througlhout the D:istrict of Kynouria (in the Prefecture of Arcadia), includes the east poart of the District of Lacedaimon and the entire District of Epidavros Limira . Or. Evangelia Balta, Director of Studies (Institute for N1eohellenic Resea rch/ National Hellenic Research Foundation). Venetians and Oltomans in the Southeast Peloponnese 169 (in the Prefecture of Laconia), and ends at Cape Malea. 1 The Ottoman archival material available to me for this particular area comprises certain unpublished fiscal registers of the Morea, deposited in the Ba§bakal1lIk Osmal1lI Al"§ivi in Istanbul, which I have gathered together over the last decade, in the course of collecting testimonies on the Ottoman Peloponnese. The material r have gleaned is very fragmentary in relation to what exists and I therefore wish to stress that th e information presented here for the first time does not derive from an exhaustive archival study for the area. Nonetheless, despite the fact that the material at my disposal covers the region neither spatially nor temporarily, in regard to the protracted period of Ottoman rule, J have decided to discuss it here for two reasons: I. -

First Announcement

FIRST ANNOUNCEMENT SUMMER UNIVERSITY “Integrated Approaches for Sustainable Development Management, Tourism and Local Products in Biosphere Reserves (BRs)” Sunday 8 July to Sunday 15 July 2018, Parnon, Greece The current call concerns the organisation of a Summer University around the themes of designation and functioning of Biosphere Reserves (BR) / within the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) programme of UNESCO. It will be held from July 8 th to July 15 th 2018 in the important and beautiful area of Parnon, Greece. It is addressed to post graduate students, young researchers and managers. Following the successful Summer Universities in Amfissa (2014), Samothraki (2016) and Sardinia (2017), the 4 th Summer University will provide capacity building around a series of topics includin g management, local development, protection and conservation. THE IDENTITY OF THE PARNON REGION The proposal for the designation of a new Biosphere Reserve in SE Peloponnese (Parnon) is based on the coexistence of very significant cultural and environmental characteristics of the area. The region has important high quality agricultural production, se aborne trade and some particular intangible heritage (language and customs) in which tourism is a fast growing activity. All the above provide ideal conditions for the development of educational prospects, particularly through Education for Sustainable Dev elopment (ESD). The region is sparsely populated : its 75 ,000 inhabitants are scattered in small towns and villages, both mountainous and coastal. The BR reference area is spread over 6 municipalities (Voria Kynouria, Notia Kynouria, Sparta, Evrota, Monemvasia, Elafonisos), including: Areas of agricultural production (farming and fishing) Areas of cultural interest e.g. -

Landscapes of the Ancient Peloponnese. a Humangeographical Approach Shipley, Graham

Landscapes of the ancient Peloponnese. A humangeographical approach Shipley, Graham Citation Shipley, G. (2006). Landscapes of the ancient Peloponnese. A humangeographical approach. Leidschrift : Cultuur En Natuur, 21(April), 27-44. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/72722 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/72722 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Landscapes of the ancient Peloponnese. A human- geographical approach Graham Shipley Landscape and environment are currently of compelling cultural significance, as fields of scholarly research, sites of artistic creativity and arenas of public concern. As both imaginative representations and material realities, landscape and environment matter as a medium for the expression of complex ideas and feelings, about beauty, belonging, access to resources, relations with nature, the past and the future, making sense of the world and people’s place in it.1 This paper suggests new approaches to the ancient history of the Peloponnese, Greece. It is intended as a spur to discussion rather than the consolidated result of complete work. It proposes that ancient historians could now go further than before in adopting ideas from geographical approaches, which may allow us to investigate – in greater depth than before – aspects such as the meanings and emotions attached to landscapes, the nature of regionalism, and the extent and nature of connections and interactions between regions and smaller units. This suggestion arises from the author’s current work on Macedonian power in the Peloponnese. The period this article deals with approximately runs from the defeat of the southern Greeks by Philip II of Macedonia in 338 BC to the Roman intervention in the Peloponnese during the 190s BC. -

FINAL Report Covering the Project Activities from 01/01/2009 to 30/06/2013

LIFE Project Number LIFE07 NAT/GR/000286 FINAL Report Covering the project activities from 01/01/2009 to 30/06/2013 Reporting Date 25/09/2013 LIFE+ PROJECT NAME or Acronym Restoration of the Pinus nigra Forests on Mount Parnonas (GR 2520006) through a structured approach (PINUS) Data Project Project location Parnonas mountain, Peloponissos, Greece Project start date: 01/01/2009 Project end date: 30/06/2013 Extension date: Total Project duration 54 months Extension months: 0 (in months) Total budget 3,035,791.00 € EC contribution: 2,270,468.09 € (%) of total costs 74.79 (%) of eligible costs 74.79 Data Beneficiary Name Beneficiary The Goulandris Natural History Museum/Greek Biotope Wetland Centre Contact person Mrs Vasiliki Tsiaoussi Postal address 14th km Thessaloniki- Mihaniona, 57001, Thermi, Greece Visit address 14th km Thessaloniki- Mihaniona, 57001, Thermi, Greece Telephone +30-2310-473320 + direct n°121 Fax: +30-2310-471795 E-mail [email protected] Project Website www.parnonaslife.gr 1 List of content 1. List of key-words and abbreviations. ................................................................................. 3 2. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4 3. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 9 4. Administrative part ............................................................................................................. 9 4.1 Description -

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY EDITED BY RICHARD J.A.TALBERT London and New York First published 1985 by Croom Helm Ltd Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 1985 Richard J.A.Talbert and contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Atlas of classical history. 1. History, Ancient—Maps I. Talbert, Richard J.A. 911.3 G3201.S2 ISBN 0-203-40535-8 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-71359-1 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-03463-9 (pbk) Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Also available CONTENTS Preface v Northern Greece, Macedonia and Thrace 32 Contributors vi The Eastern Aegean and the Asia Minor Equivalent Measurements vi Hinterland 33 Attica 34–5, 181 Maps: map and text page reference placed first, Classical Athens 35–6, 181 further reading reference second Roman Athens 35–6, 181 Halicarnassus 36, 181 The Mediterranean World: Physical 1 Miletus 37, 181 The Aegean in the Bronze Age 2–5, 179 Priene 37, 181 Troy 3, 179 Greek Sicily 38–9, 181 Knossos 3, 179 Syracuse 39, 181 Minoan Crete 4–5, 179 Akragas 40, 181 Mycenae 5, 179 Cyrene 40, 182 Mycenaean Greece 4–6, 179 Olympia 41, 182 Mainland Greece in the Homeric Poems 7–8, Greek Dialects c. -

Myth – Religion in Ancient Greece

Potsdamer Altertumswissenschaftliche Beiträge – Band 67 Franz Steiner Verlag Sonderdruck aus: Natur – Mythos – Religion im antiken Griechenland Nature – Myth – Religion in Ancient Greece Herausgegeben von Tanja Susanne Scheer Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2019 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Allgemeines Abkürzungsverzeichnis ................................................................. 9 I BEGRIFFE, KONZEPTE, METHODEN Tanja S. Scheer Natur – Mythos – Religion im antiken Griechenland: Eine Einleitung ............. 13 Katja Sporn Natural Features in Greek Cult Places: The Case of Athens .............................. 29 Richard Gordon The Greeks, Religion and Nature in German Neo-humanist Discourse from Romanticism to Early Industrialisation ..................................................... 49 Jennifer Larson Nature Gods, Nymphs and the Cognitive Science of Religion .......................... 71 II DIE VEREHRUNG DER ‚NATUR‘ BEI DEN GRIECHEN? Jan N. Bremmer Rivers and River Gods in Ancient Greek Religion and Culture ........................ 89 Esther Eidinow “They Blow Now One Way, Now Another” (Hes. Theog. 875): Winds in the Ancient Greek Imaginary .............................................................. 113 Renate Schlesier Sapphos aphrodisische Fauna und Flora ............................................................ 133 Julia Kindt Animals in Ancient Greek Religion: Divine Zoomorphism and the Anthropomorphic Divine Body ............................................................. 155 Dorit Engster Von Delphinen und ihren Reitern: -

L a K O N I A

KARYES L a k o n i a KARYATES ASSOCIATION NEWS BULETTIN Issue number 28 Spring 2021 PROGRAM "OUR ANCESTORS’ ROOTS" An initiative of the Karyates Association in view of the Karyes Laconia Memory and Culture Centre completion and operation The Karyates Association on the occasion of the creation of the Karyes Laconia Memory and Culture Center inaugurates the program "OUR ANCESTORS ROOTS". The Program’s purpose is to collect data and information on the large migration flow of our compatriots during the 20th century from their homeland, Karyes Laconia to the U.S.A., Canada, Australia, etc. Our hope is with this program to record the historical path of the Arachovites / Caryates and their families over the last 150years, so that through it the third and fourth generation descendants will be able to reconnect with the place of origin of their ancestors and come in contact with modern Greece and more specifically with the beautiful place of Karyes, Laconia, their ancestors homeland. For this purpose, the Association appeals to all compatriots, wherever they are, to reminisce about their historical family memories, to record and send us a brief history of their family. This story will start from the their first Arachovite / Caryatian ancestor who emigrated, will narrate his own course in the new place he settled and will continue unfolding the story of his descendants in the new homelands. Furthermore the description of events or incidents that highlight the social contribution of the ancestors in the new homelands, but also in Karyes will have an additional historical value. These recordings can be sent to the email address [email protected] in order to be recorded by the Association and used for the purpose of the vision of the Karyes Laconia Memory and Culture Centre. -

Optimal Utilization of Water Resources for Local Communities in Mainland

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Available online at www.sciencedirect.com AvailableScienceDirect online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Manufacturing 00 (2019) 000–000 Procedia Manufacturing 00 (2019) 000–000 www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia Procedia Manufacturing 44 (2020) 253–260 1st International Conference on Optimization-Driven Architectural Design (OPTARCH 2019) 1st International Conference on Optimization-Driven Architectural Design (OPTARCH 2019) Optimal utilization of water resources for local communities in mainland Greece (case study of Karyes, Peloponnese) a a a a G.-Fivos Sargentisa*, Panayiotis Dimitriadisa, Romanos Ioannidisa, Theano Iliopouloua, G.-Fivos Sargentis *, Panayiotis Dimitriadisb , Romanos Ioannidis , Theanoa Iliopoulou , Evangelia Frangedakib and Demetris Koutsoyiannisa Evangelia Frangedaki and Demetris Koutsoyiannis aSchool of Civil Engineering, Laboratory of Hydrology and Water Resources Development, National Technical University of Athens, Heroon a School of Civil Engineering, Laboratory of HydrologyPolytechneiou and Water 9, 157 Resources 80 Zographou, Development, Greece National Technical University of Athens, Heroon bSchool of Architecture, NationalPolytechneiou Technical 9,Unive 157 rsity80 Zographou, of Athens, PatissionGreece 42, 106 82 Athens, Greece bSchool of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens, Patission 42, 106 82 Athens, Greece Abstract Abstract Water is the basis of our civilization and the development of society is intertwined with the exploitation of water resources in variousWater is scales, the basis from of aour well civilization dug to irrigate and the a garden, development to a larg of esociety dam providing is intertwined water withand energythe exploitation for a large of area.water However, resources for in remotevarious mountainousscales, from aareas, well intermittentdug to irrigate natural a garden, water toresources a large damand highproviding seasonal water demand and energy the above for atasks large become area. -

Print Sheet Remote1

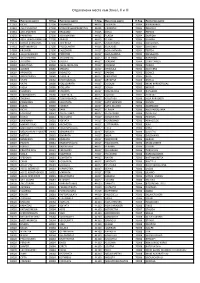

Отдалечени места към Зона I, II и III П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място 11361 KICELI 27100 KERAMIDIA 44015 LAGKADA 70004 KSEROKABOS 12351 AGIA VARVARA 27100 MONI FRAGKOPIDIMATOS 44015 LIKORRAXI 70004 PERVOLA 13561 AGII ANARGIRI 27100 TRAGANO 44015 OKSIA 70004 PEFKOS 13672 PARNITHA 27200 AGIA MARINA 44015 PLAGIA 70004 SKAFIDIA 13679 AGIA TRIADA PARNITHAS 27200 ANALICI 44015 PLIKATI 70004 STAFRIA 13679 KSENIA PARNITHAS 27200 ASTEREIKA 44015 PIRSOGIANNI 70004 SIKOLOGOS 14451 METAMORFOSI 27200 PALEOLANTHI 44015 XIONADES 70004 SINDONIA 14568 KRIONERI 27200 PALEOXORI 44017 AGIA VARVARA 70004 TERTSA 15342 AGIA PARASKEFI 27200 PERISTERI 44017 AGIA MARINA 70004 FAFLAGKOS 18010 AGIA MARINA 27300 AGIA MAFRA 44017 VEDERIKOS 70004 XONDROS 18010 AGKISTRI 27300 KALIVIA 44017 VERENIKI 70004 CARI FORADA 18010 EGINITISSA 28080 AGIOS NIKOLAOS 44017 VROSINA 70005 AVDOU 18010 ALONES 28080 GRIZATA 44017 VRISOULA 70005 ANO KERA 18010 APONISOS 28080 DIGALETO 44017 GARDIKI 70005 GONIES 18010 APOSPORIDES 28080 ZERVATA 44017 GKRIBOVO 70005 KERA 18010 VATHI 28080 KARAVOMILOS 44017 GRANITSA 70005 KRASIO 18010 VATHI 28080 KOULOURATA 44017 DIXOUNI 70005 MONI KARDIOTISSAS 18010 VIGLA 28080 POULATA 44017 DOVLA 70005 MOXOS 18010 VLAXIDES 28080 STAVERIS 44017 DOMOLESSA 70005 POTAMIES 18010 GIANNAKIDES 28080 TZANEKATA 44017 ZALOGO 70005 SFENDILI 18010 THERMA 28080 TSAKARISIANOS 44017 KALLITHEA 70006 AGIA PARASKEFI 18010 KANAKIDES 28080 XALIOTATA 44017 KATO VERENIKI 70006 AGNOS 18010 KLIMA 28080 XARAKTI 44017 KATO ZALOGO