LARGENT-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (1.196Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flesh Is Heir

cover story 125 Years of r e m o v i n g a n d Preventing t h e i l l s t o w h i c h fleSh is heiR b y b arbara I. Paull, e r I c a l l o y d , e d w I n K I ester Jr., J o e m ik s c h , e l a I n e v I t o n e , c h u c K s ta r e s I n I c , a n d sharon tregas ki s lthough the propriety of establishing a medical school here has been sharply questioned by some, “ we will not attempt to argue the question. Results will determine whether or not the promoters of the enterprise were mistaken in their judgment Aand action. The city, we think, offers ample opportunity for all that is desirable in a first-class medical school, and if you will permit me to say it, the trustees and faculty propose to make this a first-class school.” —John Milton Duff, MD Professor of Obstetrics, September 1886 More than three decades after the city’s first public hospital was established, after exhausting efforts toward a joint charter, Pittsburgh physicians founded an indepen- dent medical college, opening its doors in September 1886. This congested industrial city—whose public hospital then performed more amputations and saw more fatal typhoid-fever cases per capita than any other in the country—finally would have its own pipeline of new physicians for its rising tide of diseased and injured brakemen, domestics, laborers, machinists, miners, and steelworkers from around the world, as well as the families of its merchants, professionals, and industry giants. -

35Th Anniversary Vol

Published for Members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons 35th Anniversary Vol. XV, No. 1 Summer 2009 President’s Letter 4 Member News 6 Regulatory & Reimbursement 8 Legislative Report 10 OPTN/UNOS Corner 12 35th Anniversary of ASTS 14 Winter Symposium 18 Chimera Chronicles 19 American Transplant Congress 2009 20 Beyond the Award 23 ASTS Job Board 26 Corporate Support 27 Foundation 28 Calendar 29 New Members 30 www.asts.org ASTS Council May 2009–May 2010 PRESIDENT TREASURER Charles M. Miller, MD (2011) Robert M. Merion, MD (2010) Alan N. Langnas, DO (2012) Cleveland Clinic Foundation University of Michigan University of Nebraska Medical Center 9500 Euclid Avenue, Mail Code A-110 2922 Taubman Center PO Box 983280 Cleveland, OH 44195 1500 E. Medical Center Drive 600 South 42nd Street Phone: 216 445.2381 Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5331 Omaha, NE 68198-3280 Fax: 216 444.9375 Phone: 734 936.7336 Phone: 402 559.8390 Email: [email protected] Fax: 734 763.3187 Fax: 402 559.3434 Peter G. Stock, MD, PhD (2011) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] University of California San Francisco PRESIDENT -ELECT COUNCILORS -AT -LARGE Department of Surgery, Rm M-884 Michael M. Abecassis, MD, MBA (2010) Richard B. Freeman, Jr., MD (2010) 505 Parnassus Avenue Northwestern University Tufts University School of Medicine San Francisco, CA 94143-0780 Division of Transplantation New England Medical Center Phone: 415 353.1551 675 North St. Clair Street, #17-200 Department of Surgery Fax: 415 353.8974 Chicago, IL 60611 750 Washington Street, Box 40 Email: [email protected] Phone: 312 695.0359 Boston, MA 02111 R. -

Justice, Administrative Law, and the Transplant Clinician: the Ethical and Legislative Basis of a National Policy on Donor Liver Allocation

Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 2 2007 Justice, Administrative Law, and the Transplant Clinician: The Ethical and Legislative Basis of a National Policy on Donor Liver Allocation Neal R. Barshes Carl S. Hacker Richard B. Freeman Jr. John M. Vierling John A. Goss Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp Recommended Citation Neal R. Barshes, Carl S. Hacker, Richard B. Freeman Jr., John M. Vierling & John A. Goss, Justice, Administrative Law, and the Transplant Clinician: The Ethical and Legislative Basis of a National Policy on Donor Liver Allocation, 23 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol'y 200 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp/vol23/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, AND THE TRANSPLANT CLINICIAN: THE ETHICAL AND LEGISLATIVE BASIS OF A NATIONAL POLICY ON DONOR LIVER ALLOCATION Neal R. Barshes,* Carl S. Hacker,**Richard B. Freeman Jr.,**John M. Vierling,****& John A. Goss***** INTRODUCTION Like many other valuable health care resources, the supply of donor livers in the United States is inadequate for the number of patients with end-stage liver disease in need of a liver transplant. The supply- demand imbalance is most clearly demonstrated by the fact that each year approximately ten to twelve percent of liver transplant candidates die before a liver graft becomes available.1 When such an imbalance between the need for a given health care resource and the supply of that resource exists, some means of distributing the resource must be developed. -

St Med Ita.Pdf

Colophon Appunti dalle lezioni di Storia della Medicina tenute, per il Corso di Laurea in Medicina e Chirurgia dell'Università di Cagliari, dal Professor Alessandro Riva, Emerito di Anatomia Umana, Docente a contratto di Storia della Medicina, Fondatore e Responsabile del Museo delle Cere Anatomiche di Clemente Susini Edizione 2014 riveduta e aggiornata Redazione: Francesca Testa Riva Ebook a cura di: Attilio Baghino In copertina: Francesco Antonio Boi, acquerello di Gigi Camedda, 1978 per gentile concessione della Pinacoteca di Olzai Prima edizione online (2000) Redazione: Gabriele Conti Webmastering: Andrea Casanova, Beniamino Orrù, Barbara Spina Ringraziamenti Hanno collaborato all'editing delle precedenti edizioni Felice Loffredo, Marco Piludu Si ringraziano anche Francesca Spina (lez. 1); Lorenzo Fiorin (lez. 2), Rita Piana (lez. 3); Valentina Becciu (lez. 4); Mario D'Atri (lez. 5); Manuela Testa (lez. 6); Raffaele Orrù (lez. 7); Ramona Stara (lez. 8), studenti del corso di Storia della Medicina tenuto dal professor Alessandro Riva, nell'anno accademico 1997-1998. © Copyright 2014, Università di Cagliari Quest'opera è stata rilasciata con licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Condividi allo stesso modo 4.0 Internazionale. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Data la vastità della materia e il ridotto tempo previsto dagli attuali (2014) ordinamenti didattici, il profilo di Storia della medicina che risulta da queste note è, ovviamente, incompleto e basato su scelte personali. Per uno studio più approfondito si rimanda alle voci bibliografiche indicate al termine. Release: riva_24 I. La Medicina greca Capitolo 1 La Medicina greca Simbolo della medicina Nelle prime fasi, la medicina occidentale (non ci occuperemo della medicina orientale) era una medicina teurgica, in cui la malattia era considerata un castigo divino, concetto che si trova in moltissime opere greche, come l’Iliade, e che ancora oggi è connaturato nell’uomo. -

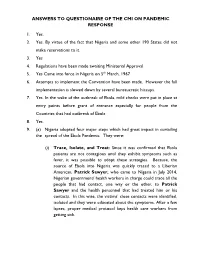

Nigeria MLA Replies to the Pandemic Response Questionnaire

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONAIRE OF THE CMI ON PANDEMIC RESPONSE 1. Yes. 2. Yes. By virtue of the fact that Nigeria and some other 190 States did not make reservations to it. 3. Yes 4. Regulations have been made awaiting Ministerial Approval 5. Yes Came into force in Nigeria on 5th March, 1967 6. Attempts to implement the Convention have been made. However the full implementation is slowed down by several bureaucratic hiccups. 7. Yes. In the wake of the outbreak of Ebola, mild checks were put in place at entry points before grant of entrance especially for people from the Countries that had outbreak of Ebola 8. Yes. 9. (a) Nigeria adopted four major steps which had great impact in curtailing the spread of the Ebola Pandemic. They were: (i) Trace, Isolate, and Treat: Since it was confirmed that Ebola patients are not contagious until they exhibit symptoms such as fever, it was possible to adopt these strategies. Because, the source of Ebola into Nigeria was quickly traced to a Liberian American, Patrick Sawyer, who came to Nigeria in July 2014, Nigerian government/ health workers in charge could trace all the people that had contact, one way or the other, to Patrick Sawyer and the health personnel that had treated him or his contacts. In this wise, the victims’ close contacts were identified, isolated and they were educated about the symptoms. After a few lapses, proper medical protocol kept health care workers from getting sick. (ii) Early Detection before many people could be exposed: It is generally believed that anyone with Ebola, typically, will infect about two more people, unless something is done to intervene. -

The Story of Organ Transplantation, 21 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1969 The tS ory of Organ Transplantation J. Englebert Dunphy Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation J. Englebert Dunphy, The Story of Organ Transplantation, 21 Hastings L.J. 67 (1969). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. The Story of Organ Transplantation By J. ENGLEBERT DUNmHY, M.D.* THE successful transplantation of a heart from one human being to another, by Dr. Christian Barnard of South Africa, hias occasioned an intense renewal of public interest in organ transplantation. The back- ground of transplantation, and its present status, with a note on certain ethical aspects are reviewed here with the interest of the lay reader in mind. History of Transplants Transplantation of tissues was performed over 5000 years ago. Both the Egyptians and Hindus transplanted skin to replace noses destroyed by syphilis. Between 53 B.C. and 210 A.D., both Celsus and Galen carried out successful transplantation of tissues from one part of the body to another. While reports of transplantation of tissues from one person to another were also recorded, accurate documentation of success was not established. John Hunter, the father of scientific surgery, practiced transplan- tation experimentally and clinically in the 1760's. Hunter, assisted by a dentist, transplanted teeth for distinguished ladies, usually taking them from their unfortunate maidservants. -

Advances and Controversies in an Era of Organ Shortages M I Prince, M Hudson

135 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.917.135 on 1 March 2002. Downloaded from REVIEW Liver transplantation for chronic liver disease: advances and controversies in an era of organ shortages M I Prince, M Hudson ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:135–141 Since liver transplantation was first performed in 1968 diminished (partially due to improvements in by Starzl et al, advances in case selection, liver surgery, road safety), resulting in the number of potential recipients for liver transplantation exceeding anaesthetics, and immunotherapy have significantly organ supply with attendant deaths of patients on increased the indications for and success of this waiting lists. We review areas of controversy and operation. Liver transplantation is now a standard new approaches developing in response to this mismatch. therapy for many end stage liver disorders as well as acute liver failure. However, while demand for IMPROVING THE RATIO OF TRANSPLANT SUPPLY AND DEMAND cadaveric organ grafts has increased, in recent years There are three approaches to improving the ratio the supply of organs has fallen. This review addresses of liver availability to potential recipients. First, to current controversies resulting from this mismatch. In maximise efficiency of liver distribution between centres; second, to examine ways of expanding particular, methods for increasing graft availability and the donor pool; and third, to impose limits on use difficulties arising from transplantation in the context of of livers for certain indications. Xenotransplanta- alcohol related cirrhosis, primary liver tumours, and tion is not currently an option for human liver transplantation. hepatitis C are reviewed. Together these three Organ distribution protocols minimise in- indications accounted for 42% of liver transplants equalities in supply and demand between regions performed for chronic liver disease in the UK in 2000. -

Impact of Ebola Virus Disease on School Administration in Nigeria

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 5, No. 3; June 2015 Impact of Ebola Virus Disease on School Administration in Nigeria Oladunjoye Patrick, PhD Major, Nanighe Baldwin, PhD Niger Delta University Educational Foundations Department Wilberforce Island Bayelsa State Nigeria Abstract This study is focused on the impact of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) on school administration in Nigeria. Two hypothesis were formulated to guide the study. A questionnaire titled Ebola Virus Disease and school administration (EVDSA) was used to collect data. The instrument was administered to one hundred and seventeen (117) teachers and eighty three (83) school administrators randomly selected from the three (3) regions in the federal republic of Nigeria. This instrument was however validated by experts and tested for reliability using the test re-test method and data analyzed using the Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient. The result shows that there is a significant difference between teachers and school heads in urban and rural areas on the outbreak of the EVD. However, there is no significant difference in the perception of teachers and school heads in both urban and rural areas on the effect of EVD on attendance and hygiene in schools. Based on these findings, recommendations were made which include a better information system to the rural areas and the sustenance of the present hygiene practices in schools by school administrators. Introduction The school and the society are knitted together in such a way that whatever affects the society will invariably affect the school. When there are social unrest in the society, the school attendance may be affected. -

Eunuchen Als Sklaven (Kordula Schnegg)

Inhaltsverzeichnis 7 Vorwort (Andreas Exenberger) 15 Körperliche Verstümmelung zur „Wertsteigerung“ – Eunuchen als Sklaven (Kordula Schnegg) 27 Mit Haut und Haar. Der menschliche Körper als Ware im Europa der Frühen Neuzeit (Valentin Gröbner) 39 Der Körper in der Psychiatrie: Psychiatrische Praxis in Tirol in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Maria Heidegger) 59 Zur Geschichte der Organtransplantation (Marlene Hopfgartner) 79 Menschliche Körperteile – Ein Monetarisierungsversuch mittels Schmerzensgeldentscheidungen (Andrea Leiter, Magdalena Thöni, Hannes Winner) 99 Menschliche Eizellen – ein kostbares Gut (Gabriele Werner- Felmayer) 119 Organknappheit? Wie lösen? Eine Zusammenfassung der Podiumsdiskussion am 15. Mai 2008 in Innsbruck (Matthias Stöckl) 133 ANHANG: Verwandlungen. Eine kleine statistische Auswahl, wie Menschen und Körperteile zu Geld werden (Josef Nussbaumer) 151 Die Autorinnen und Autoren Vorwort Einleitende Anmerkungen zum vorliegenden Band Andreas Exenberger Am 15. und 16. Mai 2008 fand in Innsbruck das 2. Wirtschaftshistorische Symposium zum Thema Von Körpermärkten statt. Diese Tagung schloss an die Vorjahresveranstaltung an, die das Thema Von Menschenhandel und Menschenpreisen behandelt hat.1 Während damals der Mensch als Ganzes in seiner Rolle als Sklave/Slavin, Gefangene(r), potentielles Unfallopfer oder Patient(in) im Mittelpunkt stand, ging es diesmal gezielt um den Körper oder Teile des- selben. Solche Körperteile waren immer schon begehrt, heute vielleicht am stärksten in der Medizin, wenn Organe oder Gewebe längst ganz real und teils sogar offen gehandelt werden, oder in der Versicherungswirtschaft, wo ganz natürlich und je nach Bedarf und Bewertung auch Teile von Menschen gegen Schäden versichert werden, wie z.B. die Stimmbänder von Opernsänger(inne)n, die Nasen von Weinkenner(inne)n, die Beine von Fußballern oder der Busen von Popsängerinnen. -

Order Paper 5 November, 2019

FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION NO. 54 237 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday 5 November, 2019 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Message from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Message from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation ______________________________________________________________ PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal College of Agriculture, Katcha, Niger State (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.403) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 2. Public Service Efficiency Bill, 2019 (HB.404) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 3. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.405) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 4. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 ((HB.406) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 5. National Rice Development Council Bill, 2019 (HB.407) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 238 Tuesday 5 November, 2019 No. 54 6. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.408) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 7. Counselling Practitioners Council of Nigeria (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.409) (Hon. Muhammad Ali Wudil) – First Reading. 8. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.410) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 9. Federal University of Medicine and Health Services, Bida, Niger State (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.411) (Hon. -

What We Can Learn from and About Africa in the Corona Crisis The

Pockets of effectiveness What we can learn from and about Africa in the corona crisis by Michael Roll, German Development Institute / D eutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) The Current Column of 2 April 2020 Pockets of effectiveness What we can learn from and about Africa in the corona crisis Is Africa defenceless in the face of the corona pandemic? This to a treatment centre. In total, 20 people became infected in would appear to be self-evident, as even health care systems Nigeria in 2014 and eight of them died. The WHO lauded the far better equipped than those of many African countries are successful contact-tracing work under very difficult condi- currently on the verge of collapse. Nonetheless, such a con- tions as a piece of “world-class epidemiological detective clusion is premature. In part, some African countries are work”. even better prepared for pandemics than Europe and the What does this mean for corona in Nigeria and in Africa? As a United States. Nigeria’s success in fighting its 2014 Ebola result of their experience with infectious diseases, many Afri- outbreak illustrates why that is the case and what lessons can countries have established structures for fighting epidem- wealthier countries and the development cooperation com- ics in recent years. These measures and the continent’s head munity can learn from it. start over other world regions are beneficial for tackling the Learning from experience corona pandemic. However, this will only help at an early stage when the chains of infection can still be broken by iden- Like other African countries, Nigeria has experience in deal- tifying and isolating infected individuals. -

BY the TIME YOU READ THIS, WE'll ALL BE DEAD: the Failures of History and Institutions Regarding the 2013-2015 West African Eb

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. George Denkey Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Denkey, George, "BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic.". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/517 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. By Georges Kankou Denkey A Thesis Submitted to the Department Of Urban Studies of Trinity College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts Degree 1 Table Of Contents For Ameyo ………………………………………………..………………………........ 3 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 6 Ebola: A Background …………………………………………………………………… 20 The Past is a foreign country: Historical variables behind the spread ……………… 39 Ebola: The Detailed Trajectory ………………………………………………………… 61 Why it spread: Cultural