Forum Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Plants Society South Gippsland Newsletter April, 2017 We Are Proud to Acknowledge Aboriginal People As the Traditional Owners of These Lands and Waters

Australian Plants Society South Gippsland Newsletter April, 2017 We are proud to acknowledge Aboriginal people as the traditional owners of these lands and waters From the Great Southern Rail Trail. February 2017 Photo by Graeme Rowe Inside this Newsletter: Twenty-three people attended our Twilight Picnic and walk to the Black Spur Creek 2017 program and other events & news Wetlands. In Graeme’s photo from the most including : easterly rail trail trestle bridge can be seen the Results of the AGM Tarwin River West Branch in left foreground, Plans for September weekend away in the its meandering course through the goldfields area of Central Victoria. middle ground, a flood plain in the foreground Vale Graeme Desmond Tuff (Tuffy) and steep valley wall in A possible new initiative for rare plants the distance. See Graeme Rowe’s article on the geomorphology inside this newsletter . 2 AUSTRALIAN PLANTS SOCIETY SOUTH GIPPSLAND GROUP For club enquiries: President 5674 2864 or Secretary 5659 8187 Program for 2017 Wednesday April 12th : 7.30 pm Uniting Church, 16 Peart Street, LEONGATHA “Revegetation – Heart Morass and Black Spur Creek Wetlands” Matt Bowler, Project Delivery Team Leader, West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority. Wednesday May 10th : 7.30 pm Uniting Church, 16 Peart Street, LEONGATHA "Gardening for Wildlife using Australian natives" Amy Akers, Australian Plant Enthusiast, Horticulturalist. More information in this newsletter – email your seed orders for Amy to bring on the night. Wednesday June 14th : 7.30 pm Uniting Church, 16 Peart Street, LEONGATHA “Gardens, Gardeners and APS Vic” Chris Long, President, APS Victoria July and August activities to be confirmed. -

10/04/2021 Laharum

Round 1 10/04/2021 Round 5 15/05/2021 Edenhope Apsley Laharum Edenhope Pimpinio Rupanyup Natimuk United Rupanyup Laharum Swifts Kaniva Leeor United Kalkee Kalkee Taylors Lake Noradjuha Quantong Swifts Natimuk United Harrow Balmoral Harrow Balmoral Pimp Balmoral Noradjuha Quantong Jeparit Rainbow Jeparit Rainbow Taylors Lake Rainbow Edenhope Apsley Kaniva Leeor United Edenhope Round 2 17/04/2021 Laharum Noradjuha Quantong Round 6 22/05/2021 Kalkee Jeparit Rainbow Rupanyup Kalkee Swifts Kaniva Leeor United Taylors Lake Swfits Pimpinio Edenhope Apsley Pimpinio Laharum Rupanyup Harrow Balmoral Harrow Balmoral Noradjuha Quantong Harrow Taylors Lake Natimuk United Natimuk United Edenhope Apsley Jeparit Rainbow Kaniva Leeor United Rainbow Round 3 24/04/2021 Swfits Rupanyup Round 7 29/05/2021 Pimpinio Kalkee Edenhope Apsley Kalkee Apsley Taylors Lake Laharum Natimuk United Laharum Natimuk United Noradjuha Quantong Kaniva Leeor United Pimpinio Jeparit Rainbow Edenhope Apsley Jeparit Noradjuha Quantong Rupanyup Kaniva Leeor United Harrow Balmoral Harrow Balmoral Taylors Lake Balmoral Jeparit Rainbow Swifts Jeparit Round 4 1/05/2021 Laharum Kalkee Round 8 5/06/2021 Swifts Pimpinio Taylors Lake Pimpinio Rupanyup Taylors Lake Swifts kalkee Edenhope Apsley Noradjuha Quantong Apsley Rupanyup Laharum Kaniva Leeor United Natimuk United Jeparit Rainbow Natimuk United Rainbow Harrow Balmoral Jeparit Rainbow Harrow Harrow Balmoral Edenhope Apsley Harrow Noradjuha Quantong Kaniva Leeor United League Bye 8/05/2021 Queens B'day 12/06/2021 Round 12 17/07/2021 -

Mt Atkinson Precinct Structure Plan (PSP1082), Victoria: Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment

Final Report Mt Atkinson Precinct Structure Plan (PSP1082), Victoria: Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment Client Metropolitan Planning Authority (MPA) 20 October 2015 Ecology and Heritage Partners Pty Ltd Cultural Heritage Advisor Authors Terence MacManus Terence MacManus and Rachel Power HEAD OFFICE: 292 Mt Alexander Road Ascot Vale VIC 3056 GEELONG: PO Box 8048 Newtown VIC 3220 BRISBANE: Level 7 140 Ann Street Brisbane QLD 4000 ADELAIDE: 8 Greenhill Road Wayville SA 5034 www.ehpartners.com.au ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the following organisations for their contribution to the project: The Metropolitan Planning Authority for project and site information. Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation for assistance in the field and provision of cultural heritage information. Boon Wurrung Foundation Limited for assistance in the field and provision of cultural heritage information. Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc. for provision of cultural heritage information. Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Unless otherwise specified, all images used in this report were produced by Ecology and Heritage Partners. Cover Photo: View from crest of Mt. Atkinson, facing northwest from the northern side. (Photo by Ecology and Heritage Partners Pty Ltd) Mt Atkinson Precinct Structure Plan (PSP1082) Victoria: Aboriginal Heritage Impact Assessment, October 2015 ii DOCUMENT CONTROL Activity Mt Atkinson Precinct Structure Plan (PSP1082) Address Project number 5874 Project manager Terence MacManus Report author(s) Terence -

Streetscape Redevelopments

Case Study 45 Streetscape Redevelopments Nhill & Dimboola VIC Representing Australia’s clay brick and paver manufacturers Think Brick Australia PO Box 751, Willoughby NSW 2068 (1/156 Mowbray Road, Willoughby) Tel (02) 8962 9500 Fax (02) 9958 5941 [email protected] www.thinkbrick.com.au Copyright 2010 © Think Brick Australia ABN 30 003 873 309 Client: Hindmarsh Shire Council Landscape architecture & urban design: Mike Smith and Associates Pavement construction: JC Contracting Streetscape redevelopment Nhill and Dimboola VIC They may be small towns nestled in Victoria’s Melbourne and Adelaide, both towns are wheatbelt, but Nhill and Dimboola are stars in struggling to retain populations, and to attract their own right. One was the subject of a and keep higher-qualified staff. Hindmarsh quirky 1997 film “The Road to Nhill” and the Shire Council brought in landscape architects other the inspiration for the famous wedding and urban designers Mike Smith and reception play (later filmed in the town). Associates as part of an urban design frame- work to make the townships more tourist and Just 40 kilometres apart on the Western resident friendly. “They looked at everything Highway and roughly equidistant from that could be improved, to make these more feasible townships for people to want to stay instead of driving straight through,” explains Peter Dawson, the shire’s properties, purchasing and contracts manager. (Top) “We are very happy with the result,” says Peter Dawson, The Nhill (the “h” is silent) plan capitalises on Hindmarsh Shire Council. (From left) Paving around the the main street’s broad median strip. Every Nhill tourist information centre day, coaches on the Melbourne–Adelaide run complements the town’s handsome architecture. -

Regional Development Victoria Annual Report RDV Annual Report 2006/07

2006/07 Regional Development Victoria Annual Report RDV Annual Report 2006/07 Contents Section 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 1.1 Chief Executive Foreword ..............................................................................................................5 Section 2.0 Overview of Regional Development Victoria ....................................................................................8 2.1 Profi le of Regional Development Victoria .........................................................................................9 2.2 Structure of Regional Development Victoria ..................................................................................10 2.3 Regional Development Advisory Committee .................................................................................12 Section 3.0 Year In Review ............................................................................................................................14 3.1 Highlights 2006/07 .....................................................................................................................15 3.2 Case Studies 2006/07 ................................................................................................................31 3.3 Regional Infrastructure Development Fund projects in review .........................................................44 3.4 Small Towns Development Fund projects in review .......................................................................51 -

2 PAST EVENTS ...3 Library NEWS ...7

wendish news WENDISHW HERITAGE SOCIETY A USTRALIA NUMBER 57 SEPTEMBER 2016 C ONTENTS Clockwise from top: CALENDAR OF UPCOMING EVENTS ........ 2 1. Tour Group members at the Nhill Lutheran Church (see page 3). PAST EVENTS ..................... 3 2. Albacutya homestead in the Wimmera – Mallee Pioneer Museum at Jeparit. LIBRARY NEWS ................... 7 3. Headstone of Helene Hampe (1840–1907), widow of Pastor G.D. Hampe, at Lochiel Lutheran TOURS ......................... 8 Cemetery. 4. Peter Gebert in his Kumbala Native Garden, near RESEARCH ...................... 9 Jeparit. 5. Daryl Deutscher, at the entrance to his Turkey Farm FROM OTHER SOCIETEIS JOURNALS ..... .10 with Glenys Wollermann, at Dadswell’s Bridge. 6. Chemist display at the Dimboola Courthouse REUNIONS ..................... .11 Museum. DIRECTORY ..................... .12 PHOTOS SUPPLIED BY CLAY KRUGER AND BETTY HUF Calendar of upcoming events 30th Anniversary Luncheon, Labour Day Weekend Tour to Saturday 15 October 2016 Portland, 11-13 March 2017 We will celebrate a special milestone this year: the Our tour leader, Betty Huf, has graciously offered to 30th Anniversary of our Society. You are warmly lead us on a tour of historic Portland on Victoria’s invited, along with family and friends, to attend this south-west coast, on 11-13 March 2017. Please note special Anniversary Luncheon to be held at 12 noon that this is the Labour Day long weekend in Victoria on Saturday 15 October in the Community Room and accommodation will need to be booked early at St Paul’s Lutheran Church, 711 Station St, Box due to the popularity of the Port Fairy Folk Festival. Hill, Victoria. (Please note that the luncheon venue The Henty family were the first Europeans to set- has been changed from the German Club Tivoli.) tle within the Port Phillip district (now known as The Church is near the corner of Whitehorse Rd Victoria), arriving at Portland Bay in 1834. -

Attachments: 2 & 3

HINDMARSH SHIRE COUNCIL COUN CIL MEETING MINUTES 19 AUGUST 2020 MINUTES OF THE COUNCIL MEETING OF THE HINDMARSH SHIRE COUNCIL HELD 19 AUGUST 2020 AT THE NHILL MEMORIAL COMMUNITY CENTRE, 77-79 NELSON STREET, NHILL COMMENCING AT 3:00PM. AGENDA 1. Acknowledgement of the Indigenous Community and Opening Prayer 2. Apologies 3. Confirmation of Minutes 4. Declaration of Interests 5. Public Question Time 6. Correspondence 7. Assembly of Councillors 7.1 Record of Assembly 8. Planning Permit Reports 8.1 Application for Planning Permit PA1673-2020 – Two Lot Subdivision in a Farming Zone at 200 E Judds Road, Yanac VIC 3418 8.2 Application for Planning Permit PA1671-2020 – Use for a Place of Assembly (Silos Viewing Area, Car Park and Access Track) – Albacutya Road Rainbow VIC 3424 (Crown Allotment 3M, Parish of Albacutya) 9. Reports Requiring a Decision 9.1 Governance Rules 9.2 Draft Public Transparency Policy 9.3 Councillor Expense Entitlements Policy 9.4 Conflict of Interest Policy Page 1 of 69 HINDMARSH SHIRE COUNCIL COUN CIL MEETING MINUTES 19 AUGUST 2020 9.5 Section 86 Committee Transition 9.6 Delegations 9.7 Financial Report for the Period Ending 30 June 2020 9.8 Domestic Animal Management Plan 2017-2021 Annual Review 9.9 Planning Policy Framework Translation 10. Special Committees 10.1 COVID-19 Revitalization Reference Group Minutes 11. Late Reports 12. Urgent Business 13. Confidential Matters 13.1 Hardship Application 13.2 Contract No. 2020-2021-01 – Panel for the Provision of Town Planning and Associated Services 13.3 Chief Executive Officer Appraisal 2019/20 14. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Horsham Parish Will Be Merged with Nhill, Warracknabeal and PARISH CONTACTS Hopetoun Parishes Into One Ministry District

Horsham-Dimboola–Murtoa–Natimuk- Rupanyup- Nhill All Saints/Souls Day - 1st November 2020 Horsham Parish will be merged with Nhill, Warracknabeal and PARISH CONTACTS Hopetoun Parishes into one Ministry District. From January Parish Priest: Fr. Peter Hudson 15th 2021, in the first 6 months of 2021, Monsignor Murphy will Parish Secretary: Camille Del Castillo prepare our Parishes for the canonical transfer into the new 10 Roberts Ave Horsham 3400 Ministry District. To help our Parishes to prepare for this, myself PO Box 212, Horsham Vic 3402 Phone:5382 1155. and Monsignor Glynn Murphy, will meet with Horsham Email: Parishioners, this Friday November 6th, in the Parish [email protected] Centre from 6pm to 7.30pm. Diocesan Website: www.ballarat.catholic.org.au 20 Parishioners can attend. Please inform Camille in the SCHOOLS Office on 53821155 if you are coming, or leave a message. Ss Michael & John Primary Principal: Andrea Cox There will be a booklet presented to guide you Phone: 5382 3000 St Brigid’s College Covid Safe Plans for coming to Mass or Church include: Principal: Peter Gutteridge • Face masks must be worn. Legal requirements apply to these Phone: 5382 3545 • Social distancing is adhered to: 4 meter square rule. Our Lady Help of Christians Principal: Cathy Grace • Names, contact numbers, time attended, MUST be recorded. Phone: 5385 2526 • Maximum number of people permitted: 20 plus faith leader. Nhill: St Patrick’s • Hand sanitiser provided. Cleaning/Sanitising protocol displayed. Principal: Kingsley Dalgleish • Reminder if people are sick or unwell do not attend, get tested • To attend 6.30pm, Sunday 9 and 10.30 Masses, please book Fr Richard Leonard will come to our Parish for an in at the Office 53821155, leave a message or phone 0419323397 Advent Mission this year • If more than 20 turn up I will ask those who didn't book, to leave DECEMBER 5th to 9th November opens up a few more areas for us to gather. -

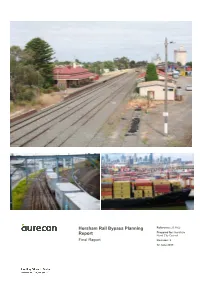

Horsham Rail Bypass Planning Report - Final Report

Horsham Rail Bypass Planning Reference: 233162 Prepared for: Horsham Report Rural City Council Final Report Revision: 3 12 June 2013 Document Control Record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Aurecon Centre Level 8, 850 Collins Street Docklands VIC 3008 PO Box 23061 Docklands VIC 8012 Australia T +61 3 9975 3000 F +61 3 9975 3444 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Document control Report Title Horsham Rail Bypass Planning Report - Final Report Document ID 233162-RPT-002 Project Number 233162 P:\RLS\233162 Horsham Rail Bypass Project\3. Project Delivery\340 File Path Deliverables\7. Final Report Rev 3\Horsham Rail Bypass Planning Report - Rev 3.docx Horsham Rural City Client Client Contact John Martin Council Rev Date Revision Details/Status Prepared by Author Verifier Approver 0 1 February 2013 Draft issued for client comment HR JPW / ST GCH JEB Final report incorporating HRCC 1 13 March 2013 HR JPW / ST GCH JEB and project team comments Revised final report expanded to include Road over Rail grade 2 17 May 2013 JPW JPW GCH JEB separation option, limited economic assessment Report updated to address HRCC comments including 3 12 June 2013 JPW JPW GCH JEB similar signalling costs for the passing loop for both options Current Revision 3 Approval Author Signature Approver Signature Name J Williams Name J Belcher Title Senior Rail Engineer Title Project Director Project 233162 File Horsham Rail Bypass Planning Report - Rev 3.docx 12 June 2013 Revision 3 Page 2 Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms 6 1. -

1 the Joint Select Committee on Future Gaming Marke

THE JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON FUTURE GAMING MARKETS MET IN COMMITTEE ROOM 2, PARLIAMENT HOUSE, HOBART ON FRIDAY, 18 AUGUST 2017 Ms LEANNE MINSHULL, DIRECTOR, THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE TASMANIA WAS CALLED VIA TELECONFERENCE AND WAS EXAMINED. CHAIR (Mr Gaffney) - Thank you, Leanne, for agreeing to discuss your paper and present to the committee. Ms MINSHULL - Thanks for the opportunity. CHAIR - We have received a copy of your report and have tabled that as part of our evidence. That is why it is important for us to speak to you, because then it can be used to help us with our report. Leanne, please give an introduction and overview of the report and how it came about. After that, members might like to ask questions about specifics within the report. Ms MINSHULL - Okay, great. I am sitting in an airport so occasionally there will get announcements in the background, but I will just plough on. The Australia Institute Tasmania is a national institute that has been in operation since about 1994. They have a long history in looking at economic policy issues, in particular jobs, unemployment and what direct and indirect jobs can be attributed to specific industries. We looked at the gaming industry, in particular, in Tasmania for two reasons. One is because we recently started a branch there. We've been open in Tasmania for about six months. It is obviously a contested issue in the community. As part of our national work we look at Australian Bureau of Statistics statistics every time the quarterly statistics come out. We noticed a few anomalies between what was being reported as direct and indirect employment in Tasmania in the gambling industry and what we would normally see using some of the ABS data. -

Mount Gambier Cemetery Aus Sa Cd-Rom G

STATE TITLE AUTHOR COUNTRY COUNTY GMD LOCATION CALL NUMBER "A SORROWFUL SPOT" - MOUNT GAMBIER CEMETERY AUS SA CD-ROM GENO 2 COMPUTER R 929.5.AUS.SA.MTGA "A SORROWFUL SPOT" PIONEER PARK 1854 - 1913: A SOUTHEE, CHRIS AUS SA BOOK BAY 7 SHELF 1 R 929.5.AUS.SA.MTGA HISTORY OF MOUNT GAMBIER'S FIRST TOWN CEMETERY "AT THE MOUNT" A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF EARLY WYCHEPROOF & AUS VIC BOOK BAY 10 SHELF 3 R 994.59.WYCH.WYCH WYCHEPROOF DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY "BY THE HAND OF DEATH": INQUESTS HELD FOR KRANJC, ELAINE AND AUS VIC BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 4 R 614.1.AUS.VIC.GEE GEELONG & DISTRICT VOL 1 1837 - 1850 JENNINGS, PAM "BY THE HAND OF DEATH": INQUESTS HELD FOR KRANJC, ELAINE AND AUS VIC BOOK BAY 14 SHELF 2 614.1.AUS.VIC.GEE GEELONG & DISTRICT VOL.1 1837 - 1850 JENNINGS, PAM "HARMONY" INTO TASMANIAN 1829 & ORPHANAGE AUS TAS BOOK BAY 2 SHELF 2 R 362.732.AUS.TAS.HOB INFORMATION "LADY ABBERTON" 1849: DIARY OF GEORGE PARK PARK, GEORGE AUS ENG VIC BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 2 R 387.542.AUS.VIC "POPPA'S CRICKET TEAM OF COCKATOO VALLEY": A KURTZE, W. J. AUS VIC BOOK BAY 6 SHELF 2 R 929.29.KURT.KUR FACUTAL AND HUMOROUS TALE OF PIONEER LIFE ON THE LAND "RESUME" PASSENGER VESSEL "WANERA" AUS ALL BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 2 R 386.WAN "THE PATHS OF GLORY LEAD BUT TO THE GRAVE": TILBROOK, ERIC H. H. AUS SA BOOK BAY 7 SHELF 1 R 929.5.AUS.SA.CLA EARLY HISTORY OF THE CEMETERIES OF CLARE AND DISTRICT "WARROCK" CASTERTON 1843 NATIONAL TRUST OF AUS VIC BOOK BAY 16 SHELF 1 994.57.WARR VICTORIA "WHEN I WAS AT NED'S CORNER…": THE KIDMAN YEARS KING, CATHERINE ALL ALL BOOK BAY 10 SHELF 3 R 994.59.MILL.NED