New Method of Rhythmic Improvisation for the Jazz Bassist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vut 20140303 – Big Bands

JAMU 20140305 – BIG BANDS (2) 10. Chicago Serenade (Eddie Harris) 3:55 Lalo Schifrin Orchestra: Ernie Royal, Bernie Glow, Jimmy Maxwell, Marky Markowitz, Snooky Young, Thad Jones-tp; Billy Byers, Jimmy Cleveland, Urbie Green-tb; Tony Studd-btb; Ray Alonge, Jim Buffington, Earl Chapin, Bill Correa-h; Don Butterfield-tu; Jimmy Smith-org; Kenny Burrell-g; George Duvivier-b; Grady Tate-dr; Phil Kraus-perc; Lalo Schifrin-arr,cond. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, April 27/29, 1964. Verve V6-8587. 11. A Genuine Tong Funeral – The Opening (Carla Bley) 2:14 Gary Burton Quartet with Orchestra: Gary Burton-vib; Larry Coryell-g; Steve Swallow-b; Bobby Moses-dr; Mike Mantler-tp; Jimmy Knepper-tb,btb; Howard Johnson-tu,bs; Leandro “Gato” Barbieri-ts; Steve Lacy-ss; Carla Bley-p,org,cond. New York, July 1967. RCA Victor LSP 3901. 12. Escalator Over the Hill (Carla Bley) 4:57 Michael Mantler-tp; Sam Burtis, Jimmy Knepper, Roswell Rudd-tb; Jack Jeffers-btb; Bob Carlisle, Sharon Freeman-h; John Buckingham-tu; Jimmy Lyons-as; Gato Barbieri-ts; Chris Woods-bs; Perry Robinson-cl; Nancy Newton-vla; Charlie Haden-b; Paul Motian-dr; Tod Papageorge, Bob Stewart, Rosalind Hupp, Karen Mantler, Jack Jeffers, Howard Johnson, Timothy Marquand, Jane Blackstone, Sheila Jordan, Phyllis Schneider, Pat Stewart-voc; Bill Leonard, Don Preston, Viva, Carla Bley- narrators. November 1968-June 1971, various places. JCOA 839310-2. 13. Adventures in Time – 3x3x2x2x2=72 (Johnny Richards) 4:29 Stan Kenton Orchestra: Dalton Smith, Bob Behrendt, Marvin Stamm, Keith Lamotte, Gary Slavo- tp; Bob Fitzpatrick, Bud Parker, Tom Ringo-tb; Jim Amlotte-btb; Ray Starlihg, Dwight Carver, Lou Gasca, Joe Burnett-mell; Dave Wheeler-tu,btb; Gabe Baltazar-as, Don Menza, Ray Florian-ts; Allan Beutler-bs; Joel Kaye-bass,bs; Stan Kenton-p; Bucky Calabrese-b; Dee Barton-dr; Steve Dweck- tympani,perc. -

A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988)

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Reynolds, Lyndon. 1975. ‘Miles et Alia’. Contact, 11. pp. 23-26. ISSN 0308-5066. ! [I] LYNDON REYNOLDS Ill Miles et Alia The list of musicians who have played with Miles Davis since 1966 contains a remarkable number of big names, including Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul, Jack de Johnette, Dave Hol l and, John McLaughlin and Miroslav Vitous. All of these have worked success fully without Miles, and most have made a name for themselves whilst or since working with him. Who can say whether this is due to the limelight given them by playing alongside , Miles, the musical rewards of working with him, or Miles's talent-spotting abili- ties? Presumably the truth is a mixture of all these. What does Miles's music owe to the creative personalities of the musicians working with him? This question is unanswerable in practice, for one cannot quan- tify individual responsibility for a group product - assuming that is what Miles's music is. It is obvious that he has chosen very creative musicians with which to work, and yet there has often been an absence of conspicuous, individual, free solo playing in his music since about 1967. It would appear that Miles can absorb musical influences without losing his balance. What we find then, is a nexus of interacting musicians, centring on Miles; that is, musicians who not only play together in various other combinations, but influence each other as well. Even if the web could be disentangled (I know not how, save with a God's-eye-view), a systematic review of all the music that lies within it would be a task both vast and boring. -

ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999) Interviewee: Art Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown Dates: June 29-30, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 96 pp. Brown: Today is June 29, 1995. This is the Jazz Oral History Program interview for the Smithsonian Institution with Art Farmer in one of his homes, at least his New York based apartment, conducted by Anthony Brown. Mr. Farmer, if I can call you Art, would you please state your full name? Farmer: My full name is Arthur Stewart Farmer. Brown: And your date and place of birth? Farmer: The date of birth is August 21, 1928, and I was born in a town called Council Bluffs, Iowa. Brown: What is that near? Farmer: It across the Mississippi River from Omaha. It’s like a suburb of Omaha. Brown: Do you know the circumstances that brought your family there? Farmer: No idea. In fact, when my brother and I were four years old, we moved Arizona. Brown: Could you talk about Addison please? Farmer: Addison, yes well, we were twin brothers. I was born one hour in front of him, and he was larger than me, a bit. And we were very close. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Brown: So, you were fraternal twins? As opposed to identical twins? Farmer: Yes. Right. -

Phil Sumpter Dir

Contact: Phil Sumpter Dir. of Marketing & Communications 215.925.9914 ext. 15 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: November 19, 2010 JAZZ GIANT DAVE HOLLAND DEBUTS 2 TIME GRAMMY-AWARD WINNING BIG BAND PROJECT AT PAINTED BRIDE DEC. 11, BAR NONE ROSTER OF TALENT TO PERFORM TWO SHOWS HOLLAND “PASSES IT ON” TO NEXT GENERATION DURING 3-DAY RESIDENCY ON AVENUE OF THE ARTS WITH CAPA HIGH SCHOOL BIG BAND MADE POSSIBLE THROUGH SUPPORT FROM PHILADELPHIA MUSIC PROJECT PHILADELPHIA – Painted Bride Art Center proudly presents the Philadelphia debut of Dave Holland’s Big Band as part of Jazz on Vine, Philadelphia’s longest continuing jazz series. Double-bassist-composer-arranger Holland leads his 13 piece all-star ensemble in two full-length shows (7pm and 9pm) on Saturday, December 11, 2010. Tickets are $25. For tickets and show info, visit paintedbride.org, call the Box Office at 215- 925-9914 or visit the Painted Bride Art Center, located at 230 Vine Street in Philadelphia. The box office is open Tuesday through Saturday, 12pm until 6pm. Crush Card holders receive a 20% discount. Students and seniors receive a 25% discount on tickets. Three days leading up to his concerts at the Bride, Mr. Holland arrives as artist-in- residence at the High School for the Creative Arts and Performing (CAPA). Using newly written charts created specifically for this special residency, Holland will lead rehearsals while discussing his creative process and approaches to arrangement and orchestration. 17 students, including one standout freshman, will work with the jazz icon for three days straight. A culminating performance will take place in CAPA’s auditorium on Friday, December 10 at 7pm. -

Jazzweek with Airplay Data Powered by Jazzweek.Com • June 8, 2009 Volume 5, Number 28 • $7.95

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • June 8, 2009 Volume 5, Number 28 • $7.95 Jazz Album No. 1: One For All, Return Of The Smooth Album No. 1: Jackiem Joyner, Lil’ Lineup (Sharp Nine) Man Soul (Artistry/Mack Avenue) World Music No. 1: Zap Mama ReCreation Smooth Single No. 1: Jackiem Joyner, “I’m (Heads Up/Concord) Waiting For You” (Artistry/Mack Avenue) Jazz Album Chart . 3 Jazz Radio Currents . 8 Smooth Jazz Album Chart . 4 Jazz Radio Panel . 11 Smooth Singles Chart . 5 Key Non-Monitored Jazz Stations . 12 World Music Album Chart. 6 Smooth Jazz Current Tracks. 13 Jazz Add Dates. 7 Smooth Jazz Station Panel. 14 Jazz Birthdays June 8 June 16 June 27 Bill Watrous (1939) Joe Thomas (1933) Elmo Hope (1923) Julie Tippett (1947) Albert Dailey (1938) June 28 June 9 Tom Harrell (1946) Jimmy Mundy (1907) Javon Jackson (1965) Cole Porter (1891) June 29 Kenny Barron (1943) June 17 Julian Priester (1935) Mick Goodrick (1945) Tony Scott (1921) June 30 Joe Thomas (1933) June 10 Lena Horne (1917) Chuck Rainey (1940) Dicky Wells (1907) Andrew Hill (1937) Gary Thomas (1961) June 20 Stanley Clarke (1951) Charnett Moffett (1967) Eric Dolphy (1928) July 1 June 11 June 21 Earle Warren (1914) Shelly Manne (1920) Jamil Nasser (1932) Leon “Ndugu” Chancler (1952) Hazel Scott (1920) June 23 July 2 Bernard Purdie (1939) Milt Hinton (1910) Herbie Harper (1920) Jamaaladeen Tacuma (1956) Helen Humes (1913) Richard Wyands (1928) June 12 George Russell (1923) Ahmad Jamal (1930) Marcus Belgrave (1936) Sahib Shihab (1925) July 3 Chick Corea (1941) Donald -

Chick Corea Bio 2015 Chick Corea Has Attained Iconic Status in Music

Chick Corea Bio 2015 Chick Corea has attained iconic status in music. The keyboardist, composer and bandleader is a DownBeat Hall of Famer and NEA Jazz Master, as well as the fourth- most nominated artist in Grammy Awards history with 63 nods – and 22 wins, in addition to a number of Latin Grammys. From straight-ahead to avant-garde, bebop to jazz-rock fusion, children’s songs to chamber and symphonic works, Chick has touched an astonishing number of musical bases in his career since playing with the genre-shattering bands of Miles Davis in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Yet Chick has never been more productive than in the 21st century, whether playing acoustic piano or electric keyboards, leading multiple bands, performing solo or collaborating with a who’s who of music. Underscoring this, he has been named Artist of the Year twice this decade in the DownBeat Readers Poll. Born in 1941 in Massachusetts, Chick remains a tireless creative spirit, continually reinventing himself through his art. As The New York Times has said, he is “a luminary, ebullient and eternally youthful.” Chick’s classic albums as a leader or co-leader include Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (with Miroslav Vitous and Roy Haynes; Blue Note, 1968), Paris Concert (with Circle: Anthony Braxton, Dave Holland and Barry Altschul; ECM, 1971) and Return to Forever (with Return to Forever: Joe Farrell, Stanley Clarke, Airto Moreria and Flora Purim; ECM, 1972), as well as Crystal Silence(with Gary Burton; ECM, 1973), My Spanish Heart (Polydor/Verve, 1976), Remembering Bud Powell (Stretch, 1997) and Further Explorations (with Eddie Gomez and Paul Motian; Concord, 2012). -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

General Catalog 2019–2020 / Edition 19 Academic Calendar 2019–2020

BERKELEY GENERAL CATALOG 2019–2020 / EDITION 19 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2019–2020 Spring Semester 2019 Auditions for Spring 2019 By Appointment Academic and Administrative Holiday Jan 21 First Day of Spring Instruction Jan 22 Last Day to Add / Drop a Class Feb 5 Academic and Administrative Holiday Feb 18 Spring Recess Mar 25 – 31 Last Day of Instruction May 10 Final Examinations and Juries May 13 – 17 Commencement May 19 Fall Enrollment Deposit Due on or before June 1 Fall Registration Jul 29 – Aug 2 Fall Semester 2019 Auditions for Fall 2019 By May 15 New Student Orientation Aug 15 First Day of Fall Instruction Aug 19 Last Day to Add/Drop a Class Sep 1 Academic and Administrative Holiday Sep 2 Academic and Administrative Holiday Nov 25 – Dec 1 Spring 2020 Enrollment Deposit Dec 2 Last Day of Instruction Dec 7 Final Examinations and Juries Dec 9 – 13 Winter Recess Dec 16 – Jan 21, 2020 Spring Registration Jan 6 – 10, 2020 Spring Semester 2020 Auditions for Spring 2020 By Oct 15 First Day of Spring Instruction Jan 21 Last Day to Add / Drop a Class Feb 3 Academic and Administrative Holiday Feb 17 Spring Recess Mar 23 – 27 Last Day of Instruction May 8 Final Examinations and Juries May 11 – 15 Commencement May 17 Fall 2020 Enrollment Deposit Due on or before June 1 Fall 2020 Registration July 27 – 31 Please note: Edition 19 of the CJC 2019 – 2020 General Catalog covers the time period of July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020. B 1 CONTENTS ACADEMIC CALENDAR ............... Inside Front Cover The Bachelor of Music Degree in Jazz Studies Juries .............................................................. -

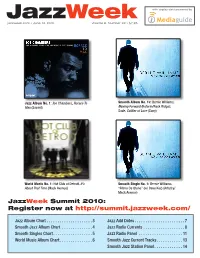

Jazzweek with Airplay Data Powered by Jazzweek.Com • June 14, 2010 Volume 6, Number 29 • $7.95

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • June 14, 2010 Volume 6, Number 29 • $7.95 Jazz Album No. 1: Joe Chambers, Horace To Smooth Album No. 1s: Bernie Williams, Max (Savant) Moving Forward (Reform/Rock Ridge); Sade, Soldier of Love (Sony) World Music No. 1: Hot Club of Detroit, It’s Smooth Single No. 1: Bernie Williams, About That Time (Mack Avenue) “Ritmo De Otono” (w/ Dave Koz) (Artistry/ Mack Avenue) JazzWeek Summit 2010: Register now at http://summit.jazzweek.com/ Jazz Album Chart .................... 3 Jazz Add Dates ...................... 7 Smooth Jazz Album Chart ............. 4 Jazz Radio Currents .................. 8 Smooth Singles Chart ................. 5 Jazz Radio Panel ................... 11 World Music Album Chart.............. 6 Smooth Jazz Current Tracks........... 13 Smooth Jazz Station Panel............ 14 Jazz Birthdays June 14 June 25 July 7 Lucky Thompson (1924) Joe Chambers (1942) Tiny Grimes (1916) June 15 June 26 Doc Severinsen (1927) Erroll Garner (1921) Dave Grusin (1934) Hank Mobley (1930) Jaki Byard (1922) Reggie Workman (1937) Joe Zawinul (1932) Tony Oxley (1938) Joey Baron (1955) July 8 June 16 June 27 Louis Jordan (1908) Joe Thomas (1933) Elmo Hope (1923) Billy Eckstine (1914) Albert Dailey (1938) June 28 July 9 Tom Harrell (1946) Jimmy Mundy (1907) Frank Wright (1935) Javon Jackson (1965) June 29 July 10 June 17 Julian Priester (1935) Noble Sissle (1899) Tony Scott (1921) Ivie Anderson (1905) June 30 Joe Thomas (1933) Cootie Williams (1911) Lena Horne (1917) Chuck Rainey (1940) Milt Buckner -

An In-Depth Analysis of Classic Jazz Compositions for a Graduate Jazz Guitar Recital Derick Cordoba Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 7-20-2007 An in-depth analysis of classic jazz compositions for a graduate jazz guitar recital Derick Cordoba Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14061511 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cordoba, Derick, "An in-depth analysis of classic jazz compositions for a graduate jazz guitar recital" (2007). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2495. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2495 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF CLASSIC JAZZ COMPOSITIONS FOR A GRADUATE JAZZ GUITAR RECITAL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by Derick Cordoba 2007 To: Dean Juan Antonio Bueno College of Architecture and the Arts This thesis, written by Derick Cordoba, and entitled An In-depth Analysis of Classic Jazz Compositions for a Graduate Jazz Guitar Recital, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Sam Lussier Gary Campbell Michael Orta, Major Professor Date of Defense: July 20, 2007 The thesis of Derick Cordoba is approved. Dean Juan Antonio Bueno College of Architecture and the Arts Dean George Walker University Graduate School Florida International University, 2007 •• 11 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS AN IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF CLASSIC JAZZ COMPOSITIONS FOR A GRADUATE JAZZ GUITAR RECITAL by Derick Cordoba Florida International University, 2007 Miami, Florida Professor Michael Orta, Major Professor The purpose of this thesis was to analyze jazz compositions by several great composers. -

The Role of the Bass in Pianoless Jazz Ensembles: 1952-2014

The Role of the Bass in Pianoless Jazz Ensembles: 1952-2014 Volume One Nikki Joanna Stedman B.Mus. (Hons) 2010 (The University of Adelaide) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide June 2016 ! !!!! TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... xii Abstract ............................................................................................................................ xxv Declaration ...................................................................................................................... xxvi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ xxvii Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Thesis Structure ................................................................................................................. 4 Conceptual Framework ..................................................................................................... 9 1) Pianoless Ensembles ................................................................................................. 9 2) Accompaniment Techniques .................................................................................. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana