Understanding Pre-Service Teachers' Motivations for Joining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

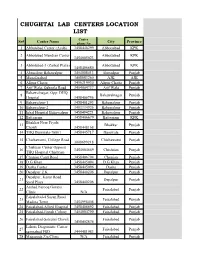

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017 Author: Muhammad Nafees Editor: Zeeshan Salahuddin Table of Contents Table of Contents ___________________________________ 3 Acronyms __________________________________________ 4 Executive Summary __________________________________ 6 Fatalities from Violence in Pakistan _____________________ 8 Victims of Violence in Pakistan________________________ 16 Fatalities of Civilians ................................................................ 16 Fatalities of Security Officials .................................................. 24 Fatalities of Militants, Insurgents and Criminals .................. 26 Nature and Methods of Violence Used _________________ 29 Key militants, criminals, politicians, foreign agents, and others arrested in 2017 ___________________________ 32 Regional Breakdown ________________________________ 33 Balochistan ................................................................................ 33 Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) ......................... 38 Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP) ....................................................... 42 Punjab ........................................................................................ 47 Sindh .......................................................................................... 52 Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), Islamabad, and Gilgit Baltistan (GB) ............................................................................ 59 Sectarian Violence .................................................................... 59 3 © Center -

Federal PSDP 2019-20 Authorization As on 17-Apr-20

Federal PSDP 2019-20 Authorization as on 17-Apr-20 (Million Rupees) Name of Project Cost Expenditure Throw- Allocation 2019-20 Authorization Upto June forward (Rupee Total Foreign Rupees Foreign Total 2019 Component) Aid Aid AVIATION DIVISION 1Construction of Airport Security 2,586.9 0.0 2,286.6 300.2 225.000 0.000 225.000 225.000 Force Camp (ASF) at IIAP 2Construction of Rain Water 2,629.4 0.0 1,638.9 990.5 100.000 0.000 100.000 100.000 Harvesting Kasana Dam 3Establishment of Specialized 2,502.5 0.0 2,446.1 56.4 3.532 20.000 23.532 3.532 Medium Range Weather Forecasting Center (SMRFC) and Strengthening of Weather Forecasting system in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 4Installation of Weather Surveillance 1,580.0 0.0 1,017.8 562.2 30.000 130.000 160.000 30.000 Radar at Karachi in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 5Installation of Weather Surveillance 1,848.7 0.0 9.0 1,839.7 30.000 20.000 50.000 30.000 Radar at Multan in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan 6New Gwadar International Airport 22,247.5 0.0 1,146.8 21,100.6 230.000 200.000 430.000 0.000 NGIA Project 7Reverse Linkage Project Between 101.0 0.0 20.0 81.0 20.500 19.500 40.000 10.250 Pakistan Meteorological Department and Marmara Research Centre (MRC), Turkey (IDB) 8Construction of Double Storey 86.9 0.0 0.0 86.9 25.000 0.000 25.000 10.000 Ladies Hostel/ Barrack with Provision of Third Storey alongwith Mess, Recreation Hall and Allied Facilities at AIIAP Lahore (53xladies staff) 9Construction of 2x Double Storey 167.6 0.0 0.0 167.6 30.000 0.000 30.000 12.000 Barrack with Provision of -

Initial Environmental Examination: Pakistan: Railway Development

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Final Project Number: TA 7528-PAK April 2011 Pakistan: Railway Development Investment Program Prepared by TERA International, Inc. The initial environmental assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 26 April 2011) Currency Unit – Rupees (PKR) PKR1.00 = $0.0118 $1.00 = PKR84.57 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biochemical oxygen demand CO – carbon monoxide COD – chemical oxygen demand dB – decibel EA – executing agency EMMP – Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan ENERCON – National Energy Conservation Center GDP – gross domestic product GoP – Government of Pakistan IEE – Initial Environmental Examination km -- kilometer m -- meter MFF – multitranche financing facility MoNP – Ministry of Nature Protection MoR – Ministry of Railways MPE – maximum permissible emissions MPL – maximum permissible loads NIDFF – National Institute of Desserts, Flora and Fauna NCCW – National Council for Conservation of Wildlife in Pakistan NEQS – National Environmental Quality Standards NOC – no-objection certificate NOx – nitrogen oxides NO2 – nitrogen dioxide PRS – Pakistan Rupees PEPO – Pakistan Environmental Protection Ordinance Pak EPA – Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency PFI – Pakistan Forest Institute QMMB – Quaid-I-Azam Mazar Management Board ROW – right-of-way RPM – respirable -

Development of High Speed Rail in Pakistan

TSC-MT 11-014 Development of High Speed Rail in Pakistan Stockholm, June 2011 Master Thesis Abdul Majeed Baloch KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 2 Foreword I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Anders Lindahl, Bo-Lennart Nelldal & Oskar Fröidh for their encouragement, patience, help, support at different stages & excellent guidance with Administration, unique ideas, feedback etc. Above all I would like to thank my beloved parents ’Shazia Hassan & Dr. Ali Hassan’ , my brothers, sisters from soul of my heart, for encouragement & support to me through my stay in Sweden, I wish to say my thanks to all my friends specially ‘ Christina Nilsson’ for her encouragement, and my Landlord ‘Mikeal & Ingmarie’ in Sweden . Finally I would like to say bundle of thanks from core of my Heart to KTH , who has given me a chance for higher education & all people who has been involved directly or in-directly with completion of my thesis work Stockholm, June 2011 Abdul Majeed Baloch [email protected] KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 3 KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 4 Summary Passenger Railway service are one of the key part of the Pakistan Railway system. Pakistan Railway has spent handsome amount of money on the Railway infrastructure, but unfortunately tracks could not be fully utilized. Since last many years due to the fall of the Pakistan railway, road transport has taken an advantage of this & promised to revenge. Finally road transport has increased progressive amount of share in his account. In order to get the share back, in 2006 Pakistan Railway decided to introduce High speed train between Rawalpindi-Lahore 1.According Pakistan Railway year book 2010, feasibility report for the high speed train between Rawalpindi-Lahore has been completed. -

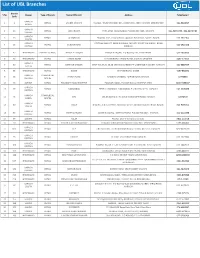

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

(Pvt) Ltd. Shop No. 01, Ground

Network Position of Exchange Companies and Exchange Companies of 'B' Category As on September 27, 2021 S# Name of Company Address Outlet Type City District Province Remarks Shop No. 01, Ground Floor, Opposite UBL, Mirpur Chowk, 1 Ravi Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Bhimber Bhimber AJK Active Mirpur Road, Bhimber, Azad Jammu & Kashmir Shop No. 01, Plot No. 67, Junaid Plaza, College Road, Near 2 Royal International Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Maqbool Butt Shaheed Chowk, Tehsil Dadyal, Distt. Mirpur Branch Dadyal Dadyal AJK Active Azad Kashmir Office No. 05, Lower Floor, Deen Trade Centre, Shaheed 3 Sky Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Kotli Kotli AJK Active Chowk, Kotli, AJK. Shop # 3&4 Gulistan Plaza Pindi Road Adjacent to NADRA 4 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Kotli Kotli AJK Active off AJK Shop # 1,2,3 Ch Sohbat Ali shopping center near NBP main 5 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Chaksawari Mirpur AJK Active bazar Chaksawari Azad Kashmir Shop No. 119-A/3, Sub Sector C/2, Quaid-e-Azam Chowk, 6 Pakistan Currency Exchange Company (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Dadyal Mirpur AJK Active Mirpur, District Mirpur, Azad Kashmir 7 Dollar East Exchange Company (Pvt.) Ltd. Shop # 39-40, Muhammadi Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Shop No. 1-A, Ground Floor, Kalyal Building, Naik Alam 8 HBL Currency Exchange (Pvt) Ltd. Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Road, Chowk Shaheedan, Mirpur, AJK Sector A-5, Opp. NBP Br., Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Azad 9 NBP Exchange Company Ltd. Branch Mirpur Mirpur AJK Active Kashmir. -

Pakistan Page 1 of 17

Pakistan Page 1 of 17 Pakistan Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 Pakistan is a federal republic. Chief of Army Staff Pervez Musharraf overthrew the elected civilian government in 1999. The Supreme Court later legitimized the overthrow, but ordered Musharraf to restore elected government within 3 years. Musharraf assumed the Presidency by decree in 2001. In 2002, a controversial national referendum affirmed Musharraf as President for 5 years. Elections for the National Assembly were held in 2002. Domestic and international observers termed the elections deeply flawed. Musharraf's Pakistan Muslim League (PML) won a plurality of seats and formed a governing coalition with several smaller parties. Indirect Senate elections in February 2003 gave the governing coalition 55 of 100 seats. In December 2003, the National and Provincial Assemblies passed the 17th Amendment to the Constitution. The Amendment transfers a number of powers from the Office of Prime Minister to the President, affirms Musharraf's presidency through 2007, sets the terms under which the President could dissolve the National Assembly, and exempts Musharraf from a prohibition on holding two offices of state until the end of the year, allowing him to remain as Chief of Army Staff. In October, over opposition protests, Parliament passed another bill that exploits a loophole in the Constitution to extend the exemption until 2007. The judiciary was nominally independent but remained subject to corruption and political pressure. Police have primary internal security responsibilities, although paramilitary forces, such as the Rangers and the Frontier Constabulary, provide support in areas where law and order problems are acute. -

Find Address of Your Nearest Loan Center and Phone Number of Concerned Focal Person

Find address of your nearest loan center and phone number of concerned focal person Loan Center/ S.No. Province District PO Name City / Tehsil Focal Person Contact No. Union Council/ Location Address Branch Name Akhuwat Islamic College Chowk Oppsite Boys College 1 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Bagh Bagh Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) Sudan Galli Road Baagh Akhuwat Islamic Muzaffarabad Road Near main bazar 2 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Dhir Kot Dhir Kot Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) dhir kot Akhuwat Islamic Mang bajri arja near chambar hotel 3 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Harighel Harighel Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) Harighel Akhuwat Islamic 4 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Bhimber Bhimber Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Kotli Mor Near Muslim & School Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 5 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Barnala Barnala Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Main Road Bimber & Barnala Road Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic Main choki Bazar near Sir Syed girls 6 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Samahni Samahni Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Microfinance (AIM) College choki Samahni Helping Hand for Adnan Anwar HHRD Distrcict Office Relief and Hattian,Near Smart Electronics,Choke 7 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Hattian Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 Development Bazar, PO, Tehsil and District (HHRD) Hattianbala. Helping Hand for Adnan Anwar HHRD Distrcict Office Relief and Hattian,Near Smart Electronics,Choke 8 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Langla Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 Development Bazar, PO, Tehsil and District (HHRD) Hattianbala. Helping Hand for Relief and Zahid Hussain HHRD Lamnian office 9 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Lamnian Zahid Hussain 0345-9071063 Development Main Lamnian Bazar Hattian Bala. -

Understanding North Punjab in the Context of Pakistani

Jan-Mar 2011 Understanding North Punjab in t he Context of Pakistani JAN -MAR 20 11 Report Understanding North Punjab in the Context of Pakistani 0 | P a g e Conflict and Peace Studies , Volume 4, Number 1 Jan-Mar 2011 Understanding North Punjab in t he Context of Pakistani Report Understanding North Punjab in the Context of Pakistani Pak Institute for Peace Studies 1. Introduction and Background 1 A census report by the Institute for Public Policy Research in London counted that 7.53 percent of Britain’s population in 2001 was born overseas. 2 Among the top non-UK birthplaces of Britain's population, Pakistan was ranked third after Republic of Ireland and India. 3 British Pakistanis mainly hail from three parts of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir: Mirpur, which has produced more than 42 percent of their over one million population in Britain, 4 and North and Central Punjab. Many British Pakistanis also belong to Peshawar, Karachi and interior Sindh. The large-scale immigration leads to various socio-cultural, religious-political and economic transformations in both the immigrants’ native areas and the host society. To understand their behaviors and interaction with the host societies, it is important to map some prevalent socio-cultural and ideological tendencies in their areas of origin, particularly the families they belong to. This exercise becomes even more pertinent where the immigrants have maintained strong links with their native towns and also feel reluctant to be fully assimilated into their host societies for one reason or another. The primary goal of this study is to measure the key religious, ideological and political trends among Pakistani immigrants hailing from North Punjab, and some adjacent parts of Central Punjab. -

List of UBL Ameen Branches to Be Opened on Saturday S

List of UBL Ameen Branches to be opened on Saturday S. No. Cluster Region District Branch Name Branch Code 1 Federal Islamabad Abbottabad District Ameen Mirpur 0355 2 Federal Islamabad North District -Islamabad Bhara Kau 1706 3 Federal Rawalpindi Chakwal District Talagang Road 0245 4 KP Azad Kashmir Mirpur District UBL Ameen MIRPUR AJK 0024 5 KP Mardan City District-Mardan KHWAJA GUNJ 0514 6 KP Mardan Timergara District BKP Batkhela 1808 7 KP Peshawar Dera Ismail Khan District Ameen daray Khan 0350 8 KP Peshawar Nowshera District UBL Ameen Akora Khattak 0290 9 KP Peshawar Cantt. District-Peshawar Ind. Estate 0042 10 KP Peshawar City District-Peshawar UBL Ameen Peshawar City 0872 11 KP Peshawar City District-Peshawar SHOBA BAZAR BRANCH, PESHAWAR 0963 12 KP Peshawar City District-Peshawar NEW FRUIT MARKET, PESHAWAR 1578 13 KP Peshawar City District-Peshawar UBL Ameen Peshawar City Sub-872 14 KP Peshawar Bannu Ameen Bannu 0515 15 Northern Punjab Gujranwala East District -Gujranwala Rail Bazar Gujranwala 0464 16 Northern Punjab Gujranwala West District -Gujranwala G. T. Road, Gujranwala 1679 17 Northern Punjab Lahore Allama Iqbal Town District -Lahore Pakki Thatti Ameen 0504 18 Northern Punjab Lahore Allama Iqbal Town District -Lahore Ichrra Ameen 0559 19 Northern Punjab Lahore Baghbanpura District -Lahore Ameen Circular Road 1275 20 Northern Punjab Lahore Bank Square District Lahore Azam Cloth 0295 21 Northern Punjab Lahore Gulberg District-Lahore UBL Ameen DHA Phase-I Lahore 0205 22 Northern Punjab Lahore Gulberg District-Lahore UBL Ameen -

To Download UBL Branch List

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI.