(Intro) Layla: I'm Layla Saad, and My Life Is Driven by One Burning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wish You All a Very Happy Diwali Page 2

Hindu Samaj Temple of Minnesota Oct, 2012 President’s Note Dear Community Members, Namaste! Deepavali Greetings to You and Your Family! I am very happy to see that Samarpan, the Hindu Samaj Temple and Cultural Center’s Newslet- ter/magazine is being revived. Samarpan will help facilitate the accomplishment of the Temple and Cultural Center’s stated threefold goals: a) To enhance knowledge of Hindu Religion and Indian Cul- ture. b) To make the practice of Hindu Religion and Culture accessible to all in the community. c) To advance the appreciation of Indian culture in the larger community. We thank the team for taking up this important initiative and wish them and the magazine the Very Best! The coming year promises to be an exciting one for the Temple. We look forward to greater and expand- ed religious and cultural activities and most importantly, the prospect of buying land for building a for- mal Hindu Temple! Yes, we are very close to signing a purchase agreement with Bank to purchase ~8 acres of land in NE Rochester! It has required time, patience and perseverance, but we strongly believe it will be well worth the wait. As soon as we have the made the purchase we will call a meeting of the community to discuss our vision for future and how we can collectively get there. We would greatly welcome your feedback. So stay tuned… Best wishes for the festive season! Sincerely, Suresh Chari President, Hindu Samaj Temple Wish you all a Very Happy Diwali Page 2 Editor’s Note By Rajani Sohni Welcome back to all our readers! After a long hiatus, we are bringing Samarpan back to life. -

Devotional Practices (Part -1)

Devotional Practices (Part -1) Hare Krishna Sunday School International Society for Krishna Consciousness Founder Acarya : His Divine Grace AC. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Price : $4 Name _ Class _ Devotional Practices ( Part - 1) Compiled By : Tapasvini devi dasi Vasantaranjani devi dasi Vishnu das Art Work By: Mahahari das & Jay Baldeva das Hare Krishna Sunday School , , ,-:: . :', . • '> ,'';- ',' "j",.v'. "'.~~ " ""'... ,. A." \'" , ."" ~ .. This book is dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder acarya ofthe Hare Krishna Movement. He taught /IS how to perform pure devotional service unto the lotus feet of Sri Sri Radha & Krishna. Contents Lesson Page No. l. Chanting Hare Krishna 1 2. Wearing Tilak 13 3. Vaisnava Dress and Appearance 28 4. Deity Worship 32 5. Offering Arati 41 6. Offering Obeisances 46 Lesson 1 Chanting Hare Krishna A. Introduction Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu, an incarnation ofKrishna who appeared 500 years ago, taught the easiest method for self-realization - chanting the Hare Krishna Maha-mantra. Hare Krishna Hare Krishna '. Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rams Rams Rama Hare Hare if' ,. These sixteen words make up the Maha-mantra. Maha means "great." Mantra means "a sound vibration that relieves the mind of all anxieties". We chant this mantra every day, but why? B. Chanting is the recommended process for this age. As you know, there are four different ages: Satya-yuga, Treta-yuga, Dvapara-yuga and Kali-yuga. People in Satya yuga lived for almost 100,000 years whereas in Kali-yuga they live for 100 years at best. In each age there is a different process for self realization or understanding God . -

Namaste: the Significance of a Yogic Greeting

Newsletter Archives Namaste: The Significance of a Yogic Greeting The material contained in this newsletter/article is owned by ExoticIndiaArt Pvt Ltd. Reproduction of any part of the contents of this document, by any means, needs the prior permission of the owners. Copyright C 2000, ExoticIndiaArt Namaste: The Significance of a Yogic Greeting Article of the Month - November 2001 In a well-known episode it so transpired that the great lover god Krishna made away with the clothes of unmarried maidens, fourteen to seventeen years of age, bathing in the river Yamuna. Their fervent entreaties to him proved of no avail. It was only after they performed before him the eternal gesture of namaste was he satisfied, and agreed to hand back their garments so that they could recover their modesty. The gesture (or mudra) of namaste is a simple act made by bringing together both palms of the hands before the heart, and lightly bowing the head. In the simplest of terms it is accepted as a humble greeting straight from the heart and reciprocated accordingly. Namaste is a composite of the two Sanskrit words, nama, and te. Te means you, and nama has the following connotations: To bend To bow To sink To incline To stoop All these suggestions point to a sense of submitting oneself to another, with complete humility. Significantly the word 'nama' has parallels in other ancient languages also. It is cognate with the Greek nemo, nemos and nosmos; to the Latin nemus, the Old Saxon niman, and the German neman and nehman. All these expressions have the general sense of obeisance, homage and veneration. -

President's Message

APRIL-MAY- JUNE-2011 Vol. 24 No. 2 OM NAMAH SHIVAYA OM NAMO NARAYANAYA President’s Message Dear Devotees, Namaste, We are proud to report another important milestone in HCCC’s history - the approval of the Master Plan Phase-1 Construction Plan. We are also glad to inform you that the City of Livermore has approved the renovation plan for the Goddess Kanaka Durga Devi facility. These achievements were possible with the efforts of many talented pro-bono volunteers, HCCC management, HCCC staff, and many generous donors. The new modern facility is designed to improve devotee convenience and comfort. The Temple Construction Committee, in association with Master Plan Committee, is in the process of selecting the general contractor and the construction will start in the next few months. To construct these (Phase I) facilities, we need to raise $4,000,000. We humbly request you all to make generous donations to help complete these facilities. Please see Appeal to Donors section in the newsletter from treasurer for sponsorship and donor recognition details. This year, due to a shortage of elected Executive Committee members, we brought in dedicated members from our diversified community, to various EC functional Chair positions. My EC team, with the help from BOD and HCCC employees, made significant achievements in the past year. Some key achievements are: • Compliance to city zoning, CUP conditions, and county health codes • Streamlining of the administration and operations • Keeping of facilities clean • Compliance with federal, state, and local -

About the Author S

About the Author S. Swaminathan, was born in Pudukottai, Tamilnadu in 1940. After professionally qualifying in Mechanical Engineering, he worked in Indian Institute of Technology - Delhi for more than 30 years and retired as Professor of Mechanical Engineering,. As a serious teacher he has attempted a number of experiments in teaching, like no-classroom teaching and holistic approach to engineering disciplines. In his view the thrust of the science and technology establishment should be towards helping the ‘poorest of the poor’. His research and development activities were primarily in this direction. He is also a social activist and participates in socially relevant projects. He worked in Centre for Rural Development in IIT Madras, Bharath Gyan Vigyan Samithy, Delhi as the National Coordinator for watershed development and Integrated Rural Technology Centre, Palakkad, Kerala. Holding to his belief that technology must be human-centred and that there exists a cultural route to development, he even taught a course titled ‘Art and Technology’ at Indian Institute of Technology-Delhi along with a colleague of his. Realising that Indian youth have an inadequate understanding of our heritage, and consequently lack a sense of identity, Prof Swaminathan decided to acquaint the students of IIT Delhi with various aspects of our culture. Not being an expert in the field, he found, may sometimes be an advantage, as audience are not put off by jargon, and interact with the speaker in an uninhibited manner. The topics included Indian music, Sanskrit, ancient Tamil literature, Tamil prosody, development of scripts, Gandhian philosophy, etc. He has made a very detailed study of Ajanta paintings. -

Namaste - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Namaste - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Namaste Namaste From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Namaste (/ˈnɑː məsteɪ/, Ⱦȱȸ -m əs-tay ; Sanskrit: नमते; Hindi: [n əməste ː]), sometimes expressed as Namaskar or Namaskaram , is a customary greeting when people meet or depart. [1][2] It is commonly found among Hindus of the Indian Subcontinent, in some Southeast Asian countries, and diaspora from these regions. [3][4] Namaste is spoken with a slight bow and hands pressed together, palms touching and fingers pointing upwards, thumbs close to the chest. This gesture is called Añjali Mudr ā or Pranamasana .[5] In Hinduism it means "I bow to the divine in you". [3][6] Namaste or namaskar is used as a respectful form of greeting, acknowledging and welcoming a relative, guest or stranger. It is used with goodbyes as well. It is typically spoken and simultaneously performed with the palms touching gesture, but it may also be spoken without acting it out or performed wordlessly; all three carry the same meaning. This cultural practice of salutation and valediction originated in the Indian A Mohiniattam dancer making a subcontinent.[7] Namaste gesture Contents 1 Etymology, meaning and origins 2 Uses 2.1 Regional variations 3 See also 4 References 5 External links Etymology, meaning and origins Namaste (Namas + te, Devanagari: नमः + ते = नमे) is derived from Sanskrit and is a combination of the word "Nama ḥa " and the enclitic 2nd person singular pronoun " te ".[8] The word " Nama ḥa " takes the Sandhi form "Namas " before the sound " t ".[9][10] Nama ḥa means 'bow', 'obeisance', 'reverential salutation' or 'adoration' [11] and te means 'to you' (dative case). -

“SALAM NAMASTE” SEBAGAI PENGUATAN IDENTITAS SOSIAL BERBASIS KEARIFAN LOKAL Yovita Arie Mangesti1

Mimbar Keadilan Volume 14 Nomor 1 Februari 2021 Yovita Arie Mangesti PERLINDUNGAN HUKUM PEMBERIAN HAK CIPTA ATAS “SALAM NAMASTE” SEBAGAI PENGUATAN IDENTITAS SOSIAL BERBASIS KEARIFAN LOKAL Yovita Arie Mangesti1 Abstract "Salam Namaste" is a gesture of placing your palms together on your chest and bending your body slightly, which is commonly practiced by Indonesians as a symbol of respect for someone they meet. This body gesture is a safe way of interacting during a pandemic, because it can minimize virus transmission through body contact without losing the noble meaning of human interaction with each other. "Salam Namaste" is a means of communication that unites the diversity of Indonesian cultures. This paper uses a conceptual, statutory and eclectic approach to "Salam Namaste" which is a form of traditional cultural expression. Indonesian culture is full of wisdom, so that "Salam Namaste" deserves legal protection in the form of State-owned Intellectual Property Rights as regulated in Article 38 of Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 28 of 2014 concerning Copyright. Keywords: copyright; local wisdom "Salam Namaste"; strengthening of social identity Abstrak “Salam Namaste” merupakan gestur tubuh mengatupkan kedua telapak tangan di dada dan sedikit membungkukkan badan, yang lazim dilakukan oleh masyarakat Indonesia sebagai simbol penghormatan terhadap seseorang yang dijumpai. Gestur tubuh ini menjadi cara berinteraksi yang aman di masa pandemi, karena dapat meminimalisir penularan virus lewat kontak tubuh tanpa kehilangan makna luhur interaksi manusia dengan sesamanya. “Salam Namaste” menjadi sarana komunikasi yang menyatukan keragaman budaya Indonesia. Tulisan ini menggunakan pendekatan konseptua, perundang-undangan serta eklektik terhadap “Salam Namaste” yang merupakan suatu bentuk ekspresi budaya tradisional. -

Dhananjay-Celibacy-Questions-And

http://en.allexperts.com/q/CelibacyAbstinence3564/ *** Question Hello Sir, Suppose an adolescent gets caught in pornography's trap and gets addicted to mas turbation in his late teens and early twenties. Does his continued indulgence in troduce demoniac entities into his gross body? Also, when he hugs his parents, d oes the bad karma get transferred to parents (or anyone else he interacts with) also? How can one develop sufficient strength and will power to completely eliminate s uch tendencies, which are deep rooted in one's consciousness ? Answer Hello Amit, Hope you are keeping well. Coming to the answers, Demonic entities are astral in nature and hence invade the astral body. Indulgin g in pornography and masturbation drains the body of positive Prana and thus att racts decay, degeneration and negative energies. This results in corrupting the mind, body and the psyche and thus leads to overall downfall in every sphere of life. Since negative entities associate themselves with negative acts, long indu lgence in porn related activities does make one come under the influence of nega tive tendencies and entities. Hugging a person cannot transfer one's karma to the other under normal circumsta nces. However, as in the case of constant association, the vibrations given out by a person affect the minds of those around him or her. We feel positive and di vine in the company of the pious and virtuous and become negative in the company of wicked and evil people. Success in attaining a pure state of mind comes after a long time based on one's past karma further to constant efforts, determination and honesty in the practi ce of virtue and purity. -

Shiva-Vishnu Temple

JUL-AUG-SEP-2006 Vol.19 No.3 PLEASE NOTE THE SCHEDULES DIRECTIONS From Freeway 580 in Livermore: Monday Through Thursday: 9 am to 12 noon Exit North Vasco Road, left on Scenic Ave, and 6 pm to 8 pm Left on Arrowhead Avenue F r i d a y, Weekends & Holidays: 9 am to 8 pm NEWS FROM THE HINDU COMMUNITY AND CULTURAL CENTER, LIVERMORE VISIT OUR WEB SITE AT http://www.livermoretemple.org SHIVA-VISHNU TEMPLE OM NAMAH SHIVAYA TELEPHONE (925) 449-6255 FAX (925) 455-0404 OM NAMO NARAYA N AYA ASHTOTHARA ARCHANA SCHEDULE FOR PLEASE NOTE SATURDAYS & SUNDAYS Shiva Ganesha Balaji Other Deities If you would like to receive a copy of this newsletter free of charge to your home address in USA, please ask for a card at the main office, fill it up and return. 10:45 am 10:15 am 10:30 am All the past issues of this newsletter are available at the Temple Website in PDF format. (Saturdays only) If you would like to be informed of all Temple Events, you can receive a weekly email 11:30 am 11:15 am 11:00 am 11:45 am with links to Temple web pages. To subscribe to this, visit the Temple website 12:30 pm 12:15 pm 12 noon 12:45 pm w w w. L i v e r m o r e Temple.org and enter your email address in the box provided at the left hand side 1:15 pm 1:30 pm 1:45 pm of the page and click on “Join Mailing List” button that is right below the box. -

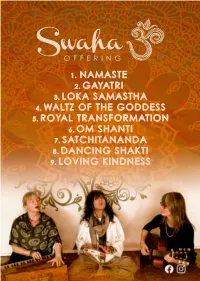

SWAHA-CD-Lyrics.Pdf

1. NAMASTE 2. GAYATRI 3. LOKA SAMASTHA 4. WALTZ OF THE GODDESS 5. ROYAL TRANSFORMATION 6. OM SHANTI 7. SATCHITANANDA 8. DANCING SHAKTI 9. LOVING KINDNESS NAMASTE Namaste, Namaste, I bow, to the soul within. When I rest in my heart, and you rest in yours, we are one, we are one. Hari Om In yoga we greet each other with the auspicious salutation, “Namaste”. Instead of simply saying “hello” to the physical form of another, the word “Namaste” acknowledges that the spirit/soul/light within me, honours that same spirit/soul/light within you. The heart is where we most easily feel connection to this inner space, therefore when we say “Namaste” we also place the hands into prayer mudra (anjali) at the centre of the chest. From our hearts to yours….Namaste. GAYATRI Om Bhur Bhuvah Swaha Tat Savitur Varenyam Bhargo Devasya Dimahi Diyoyonah Prachodayat Gayatri Mantra is an ancient mantra from the Rig Veda and it honours and appreciate the sun, not just as the earth’s source of light, heat and nourishment, but also as a symbol of the light that lives within us all. A translation of this mantra is: “The eternal earth, air and heaven. That glory, the resplendence of the sun. May we contemplate the brilliance of that light. May the sun inspire our minds.” LOKA SAMASTHA Loka Samastha Loka Samastha Sukino Bhavantu May all beings everywhere in the world x2 May all beings be happy and free. There is no better sentiment than to wish all beings everywhere to be well. The beauty of reciting this mantra is that we cultivate compassion within ourselves and we become less selfish and self-absorbed. -

Resource Guide for Recruiting Excellent and Diverse Faculty

RESOURCE GUIDE FOR RECRUITING EXCELLENT AND DIVERSE FACULTY Community Resource Guide Black Faculty and Staff Association The city of Ames is a medium sized college This FSA has an active Diversity and Inclusion town just 30 minutes north of Iowa’s largest website and an active Facebook page. metropolitan area, Des Moines. Although the State of Iowa is commonly regarded otherwise, Facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/ Iowa has been on the forefront of social justice IsuBlackFacultyStaffAssociation and equal rights issues throughout most of its Website: https://www.diversity.iastate.edu/ history. Iowa State University (“ISU”) works connect/fsa/bfsa tirelessly to continue this tradition forward in building an environment of cultural competence with its annual Thomas L. Hill Iowa State Colegas, Building Community Conference on Race and Ethnicity (“ISCORE”). Colegas is ISU’s Hispanic and Latinx Faculty The following are community resources both on and Staff Association. Although this group campus and in the surrounding community of has a website on the Diversity and Inclusion Ames, Iowa: webpage, it uses a Facebook page for most of its activities. Faculty and Staff Associations ISU has several groups right on campus. ISU Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/ calls its groups Faculty and Staff Associations IowaStateUniversityColegas. (“FSAs”). Website: https://www.diversity.iastate.edu/ connect/fsa/colegas American Indian Faculty and Staff Council This FSA does not have a Facebook group and Iowa State Christian Faculty and Staff Association does not appear to have regularly scheduled This FSA is active on Facebook. It does not events on the Diversity and Inclusion have a corresponding FSA page on the webpage. -

HINDUISM Part 1 Unit 2: Living As a Hindu

HINDUISM Part 1 Unit 2: Living as a Hindu What this unit contains What does it mean to be a Hindu? Respect for other people (shown through namaste) and respect for all living things because God is in everything. Understanding more about God and Hindu values through the stories of the birth of Krishna, Krishna and Sudhama and Murugan and Ganesh. Values: The importance of caring for others and respect for parents. Belief that God is seen in different ways and represented through different forms. Worship in the home: The shrine; The Arti ceremony; Prasad (food offered, blessed and served after prayer). Where the unit fits and how it builds This is the second Unit of Hinduism in the Primary phase. It develops pupils' knowledge and upon previous learning understanding of Hindu beliefs about God from unit 1 by introducing them to a second avatar of Vishnu. Extension activities and further thinking Think of a time when you won a competition and how you behaved towards the losers. Vocabulary SMSC/Citizenship Hinduism Shiva worship prasad Worship of God Hindu Murugan shrine prayer Sportsmanship God Ganesh adoption respect Respect for all people. belonging Krishna foster honesty Respect for all living things. namaste Sudhama Arti truthfulness Concept of God being in all creation. Agreed Syllabus for Religious Education Teaching unit HINDUISM Part 1 Unit 2:1 HINDUISM Part 1 Unit 2: Living as a Hindu Unit 2 Session 1 A A Learning objectives T T Suggested teaching activities Sensitivities, points to 1 2 note, resources Pupils should: √ Explore & demonstrate greetings known by the class, celebrating the languages Resources and cultures represented.