Typography and Motion Graphics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing Glitch Procedures and Visualisation Workflows for Markerless Live Motion Capture of Contemporary Dance

Designing Glitch Procedures and Visualisation Workflows for Markerless Live Motion Capture of Contemporary Dance Stephan Jürgens Nuno N. Correia Raul Masu ITI/LARSyS University of Greenwich ITI/LARSyS Funchal, Portugal London, UK Funchal, Portugal [email protected] ITI/LARSyS FCT - NOVA University of Lisbon Funchal, Portugal Lisbon, Portugal [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT presence, not to mention the much lower price point of these sys- This paper presents a case study in the exploration and creative tems. To work with markerless live motion capture in contemporary usage of errors and glitches in the real-time markerless motion cap- dance, both in rehearsal and performance, provides exciting op- ture of contemporary dance. We developed a typology of MoCap portunities to explore real-time motion visualisations, combining failures comprised of seven categories, allowing the user to situate physical and virtual dimensions of reality. each distinct error in the respective stage of the motion capture In our paper we will use the term ‘mixed reality set-up’ in ac- pipeline. This way, glitch procedures for the creative use of ‘bad’ cordance with previous work in the field of Human-Computer MoCap data were designed, resulting in uncommon avatar visuali- Interaction (HCI) by Gagneré and Plessiet [4]. These authors’ use of sations. We propose an additional ‘re-visualisation’ module in our the term parallels media theorist Chris Salter’s definition of mixed motion capture pipeline and avatar staging approach, which enables reality: “Interdisciplinary research area examining the hybrid inter- choreographers and digital artists to rapidly prototype their ideas action of physical and virtual elements (e.g. -

C a N Y O N C I N E M a Z I N E I S S U E N O 3 2 0 1 4 2 0

CANYONCI NEMAZINE ISSUENO3 20142015 on sound Cover: hand-painted slide by Taryn CONTRIBUTORS ONLINE CONTRIBUTORS Jones, 2013 Inside Cover: collage by Linda Bruce Baillie Jaime Cleeland Scobie, 2014 Michael Betancourt D. Jesse Damazo Brian Darr Robert Edmondson MASTHEAD John Davis Trevor Jahner Michael Daye Philip Mantione Canyon Cinemazine Clint Enns Petri Kuljuntausta An assemblage of experimental Gerry Fialka Michael Reisinger for Sleeping film and video writing, Walter Forsberg Giant Glossolalia art, and ephemera. Paul Glabicki Ken Paul Rosenthal P.O. Box 16163 Max Goldberg Phil Solomon Oakland, CA 94610 Barbara Hammer Ashley Swendsen [email protected] Emma Hurst www.cinemazine.net Joey Izzo w/John Zorn Taryn Jones Editor/Design Courtney Fellion Janis Crystal Lipzin Sounds Editor A.G. Nigrin A Wyman Michael Walsh Screenings Roger D. Wilson Linda Scobie With assistance from ABOUT THE FLEXI-DISC INSERT Charlie Biando Laura Conway A flexi-disc is a phonograph record made of thin, flexible vinyl. The F. O’Neill Phaedra Restad flexi included in this issue plays on a standard record player at 33rpm. Hannah Schulman Designed for magazine promotions, this sound object is particularly Kel Shipley delicate and degrades after about 50 plays. Like the printed page and worn film reel, this object is made to disappear, and a fitting addition to Thanks to Craig Baldwin a publication devoted to transcient images (and sounds). This project would not be possible without a generous grant from Southern Exposure’s Alternative FLEXI-DISC TRACKS & CONTRIBUTORS Exposure program - www.soex.org. John Davis, “Wild Air Moon” This project is an entirely not-for- GX Jupitter Larsen, “A Noisy Delivery” profit art experiment - all funds Jodie Mack, “Let Your Light Shine (B-Side)” generated by sales and donations go directly into funding the next See last page for more information. -

Synchronization and Title Sequences: Audio-Visual Semiosis in Motion

Synchronization and Title Sequences Synchronization and Title Sequences proposes a semiotic analysis of the synchronization of image and sound in motion pictures using title sequences. It is the second volume in Michael Betancourt’s study of semiotics and cinema using the title sequence as a critical focus, allowing for a consideration of fundamental theoretical issues apart from both the issues of narrative and realism common to commercial media. Through detailed historical close readings of title designs that use either voice-over, an instrumental opening, or title song to organize their visuals—from Vertigo (1958) to The Player (1990) and X-Men: First Class (2011)— author Michael Betancourt develops a foundational framework for the critique and discussion of motion graphics’ use of synchronization and sound, as well as a theoretical description of how sound-image relation- ships develop on-screen. The resulting study of synchronization is both a critical analysis and a theory of visual music in cinema. Michael Betancourt is an artist/theorist concerned with digital technol- ogy and capitalist ideology. His writing has been translated into Chinese, French, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Persian, Portuguese, and Spanish, and been published in magazines such as The Atlantic, Make Magazine, Millennium Film Journal, Leonardo, Semiotica, and CTheory. He wrote The ____________ Manifesto, and other books such as The Critique of Digital Capitalism, The History of Motion Graphics, Glitch Art in Theory and Practice, and Beyond Spatial Montage: Windowing. These publica- tions complement his movies, which have screened internationally at the Black Maria Film Festival, Art Basel Miami Beach, Contemporary Art Ruhr, Athens Video Art Festival, Festival des Cinemas Differents de Paris, Anthology Film Archives, Millennium Film Workshop, the San Francisco Cinematheque’s Crossroads, and Experiments in Cinema, among many others. -

Cinema’ As a Modernist Conception of Motion Pictures

http://dx.doi.org/10.25038/am.v0i16.254 Michael Betancourt Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, Georgia, USA ‘Cinema’ as a Modernist Conception of Motion Pictures Abstract: In the 1960s and 1970s the Clement Greenberg’s Modernist ideology of ‘purity’ played a central role in the definition of ‘avant-garde cinema’ as a serious, major genre of film. This transfer between ‘fine art’ and ‘avant-garde film’ was articulated as ‘structural film’ by P. Adams Sitney. This heritage shapes contemporary debates over ‘postcinema’ as digital technol- ogy undermines the ontology and dispositive of historical cinema. Its discussion here is not meant to reanimate old debates, but to move past them. Keywords: avant-garde film; postcinema; film ontology; digital cinema This paper outlines the role played by Modernist ideology in the critical/his- torical discourse of ‘cinema,’ using the avant-garde film as a case study. In consid- ering the issues around this specific “dispositive of historical cinema”1 in the period between 1960 and 1980, the focus of the following discussion is on textual analysis of critical/historical writing and issues of the canon emergent from it, rather than on particular close readings of specific films or the parallel developments in commercial ‘art cinema’. This discourse-analysis follows from the critical emergence of ‘postcine- ma,’ and its problematics for established definitions of cinema-as-art. The conception of ‘cinema’ has always been linked to Modernist aesthetics of the twentieth century. The neglect of avant-garde film – which is still often excluded from the category of ‘art cinema,’ as well as the marginalization of animation, motion graphics and visual effects – reveals its continuing impact: in/as presumptive differences between com- mercial cinema, avant-garde film, and video art. -

Ebook Download the History of Motion Graphics 1St Edition Ebook

THE HISTORY OF MOTION GRAPHICS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Betancourt | --- | --- | --- | 9781434441508 | --- | --- The History of Motion Graphics 1st edition PDF Book More information about this seller Contact this seller 9. Greyscalegorilla greyscalegorilla. No Jacket. What is motion design? Ramsey and Harold R. The motion graphics we see today on the internet, featuring various digital applications and production techniques, are changing the way we create and interact with this medium. Minor wear to the extremities. Winning over 70 national and international awards, his work is featured in popular films such as Philadelphia, Beetlejuice, Men in Black, and A Clockwork Orange. Maya vs Cinema 4D: How to orient yourself in choosing the right software. Many years ago, there was a time when the only known graphic design was only that flat and static. Animations are a perfect way to promote blogs and other social media outlets. Contact Info Triplet 3D Inc. Our BookSleuth is specially designed for you. The film depicts the rotoreliefs alternated with spinning puns in French. Tightly bound. As an animator and filmmaker, Norman McLaren was a pioneer in a number of areas of animation and filmmaking, including drawn-on-film animation, visual music, abstract film, pixilation and graphical sound. Interiros clean. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. In this, bananas are used to symbolize life and the subconscious and conscious in this strange and quirky motion graphic. This perfectly addresses the gap in educational equality and provides useful information on how to close the access gap, making it one of those motion graphic examples that blends great design with educational content. -

Ideologies of the Real in Title Sequences, Motion Graphics and Cinema

Ideologies of the Real in Title Sequences, Motion Graphics and Cinema This book explores the question of realism in motion pictures. Specifically, it explores how understanding the role of realism in the history of title sequences in film and television can illuminate discussions raised by the advent of digital cinema. Ideologies of the Real in Title Sequences, Motion Graphics and Cinema fills a critical and theoretical void in the existing literature on motion graphics. Developed from careful analysis of André Bazin, Stanley Cavell, and Giles Deleuze’s approaches to cinematic realism, this analysis uses title sequences to engage the interface between narrative and non-narrative media to consider cinematic realism in depth through highly detailed close readings of the title sequences for Bullitt (1968), Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974), The Number 23 (2007), The Kingdom (2008), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), and the James Bond films. From this critique, author Michael Betancourt develops a modal approach to cinematic realism where ontology is irrelevant to indexicality. His analysis shows the continuity between historical analogue film and contemporary digital motion pictures by developing a framework for rethinking how realism shapes interpretation. Michael Betancourt is a critical theorist and research artist concerned with digital technology and capitalist ideology. His writing has been translated into Chinese, French, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Persian, Portuguese, and Spanish, and published in journals such as The Atlantic , Make Magazine , CTheory, and Leonardo. He is the author of The ____________ Manifesto , and many books, including The History of Motion Graphics and The Critique of Digital Capitalism , as well as four books on the semiotics of motion graphics: Semiotics and Title Sequences, Synchronization and Title Sequences , Title Sequences as Paratexts , and Typography and Motion Graphics . -

Beyond Spatial Montage

Beyond Spatial Montage Beyond Spatial Montage: Windowing, or the Cinematic Displacement of Time, Motion, and Space oers an extended discussion of the morphology and structure of compositing, graphic juxtaposition, and montage employed in both historical and contemporary motion pictures. Drawing from the history of avant-garde and commercial cinema, as well as studio-based research, media theorist/artist Michael Betancourt critiques cinematic realism and spatial montage in motion pictures. This new taxonomic framework for conceptualizing linkages between media art and narrative cinema opens new areas of experimentation for today’s lm editors, motion designers, and other media artists. Michael Betancourt is an internationally exhibiting artist/historian and critical theorist. His publications and books include The ____________ Manifesto, The History of Motion Graphics: From Avant-Garde to Industry in the United States and The Critique of Digital Capitalism. He has written for both scholarly and academic publications such as The Atlantic, CTheory, Leonardo, Make Magazine, Millennium Film Journal and Semiotica, and his writing has been translated into Chinese, French, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Persian, Portuguese, and Spanish. This page intentionally left blank Beyond Spatial Montage Windowing, or the Cinematic Displacement of Time, Motion, and Space Michael Betancourt First published 2016 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2016 Michael Betancourt The right of Michael Betancourt to be identied as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

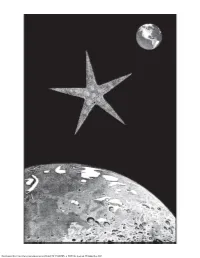

The Semiotics of the Moon As Fantasy and Destination

Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/LEON_a_00919 by guest on 30 September 2021 reimagining the moon a r t i s t ' s a r t i c l e The Semiotics of the Moon as Fantasy and Destination M i c h a e l B e T a n c o u r T T This essay surveys a 20-year period of the author’s studio-based Sitney’s discussion of “absolute animation” (a.k.a. abstract research into “spatial montage” and windowing, elaborating on his film/visual music) identifies this transcendent tradition RAC use of space imagery in a symbolic system describing the critique of through discussions of artists such as Len Lye, John Whit- BST fantasy::reality through symbols that are still used in the contemporary a ney and Harry E. Smith. The visionary iconography Sitney world---how the mythic dimensions of interpreting the “heavens” collide and contradict contemporary scientific interpretations. “Visionary” art discusses provides a way to address how our interpretations is the dynamic focus, with the Moon as the central icon, providing a unconsciously reiterate earlier symbols through forms with direct means for the author to consider ambiguities and complexities multiple meanings (Fig. 1). My imagery invokes, then cri- of symbolic transformation: earlier descriptions of heavens and tiques through conceptual dissonance, Sitney’s “visionary” Earth provide a visionary subtext to scientific exploration. The author tradition in both abstract art and visual music. These forms considers himself a “revisionary” artist whose work engages the implicit have a direct relationship to the esoteric ideas of Robert semiotics of visionary film/visual music to problematize the pseudo- scientific theories found there.