Population Trends of Spectacled Petrels Procellaria Conspicillata and Other Seabirds at Inaccessible Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S41467-020-18361-4.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18361-4 OPEN Seafloor evidence for pre-shield volcanism above the Tristan da Cunha mantle plume ✉ Wolfram H. Geissler 1 , Paul Wintersteller 2,3, Marcia Maia4, Anne Strack3, Janina Kammann5, Graeme Eagles 1, Marion Jegen6, Antje Schloemer1,7 & Wilfried Jokat 1,2 Tristan da Cunha is assumed to be the youngest subaerial expression of the Walvis Ridge hot spot. Based on new hydroacoustic data, we propose that the most recent hot spot volcanic 1234567890():,; activity occurs west of the island. We surveyed relatively young intraplate volcanic fields and scattered, probably monogenetic, submarine volcanoes with multibeam echosounders and sub-bottom profilers. Structural and zonal GIS analysis of bathymetric and backscatter results, based on habitat mapping algorithms to discriminate seafloor features, revealed numerous previously-unknown volcanic structures. South of Tristan da Cunha, we discovered two large seamounts. One of them, Isolde Seamount, is most likely the source of a 2004 submarine eruption known from a pumice stranding event and seismological analysis. An oceanic core complex, identified at the intersection of the Tristan da Cunha Transform and Fracture Zone System with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, might indicate reduced magma supply and, therefore, weak plume-ridge interaction at present times. 1 Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Am Alten Hafen 26, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany. 2 Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, Klagenfurter Str. 4, 28359 Bremen, Germany. 3 MARUM—Center of Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Leobener Str. 8, 28359 Bremen, Germany. 4 CNRS-UBO Laboratoire Domaines Océaniques, Institut Universitaire Européen de la Mer, 29280 Plouzané, France. -

Beetles of the Tristan Da Cunha Islands

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Koleopterologische Rundschau Jahr/Year: 2013 Band/Volume: 83_2013 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hänel Christine, Jäch Manfred A. Artikel/Article: Beetles of the Tristan da Cunha Islands: Poignant new findings, and checklist of the archipelagos species, mapping an exponential increase in alien composition (Coleoptera). 257-282 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Koleopterologische Rundschau 83 257–282 Wien, September 2013 Beetles of the Tristan da Cunha Islands: Dr. Hildegard Winkler Poignant new findings, and checklist of the archipelagos species, mapping an exponential Fachgeschäft & Buchhandlung für Entomologie increase in alien composition (Coleoptera) C. HÄNEL & M.A. JÄCH Abstract Results of a Coleoptera collection from the Tristan da Cunha Islands (Tristan and Nightingale) made in 2005 are presented, revealing 16 new records: Eleven species from eight families are new records for Tristan Island, and five species from four families are new records for Nightingale Island. Two families (Anthribidae, Corylophidae), five genera (Bisnius STEPHENS, Bledius LEACH, Homoe- odera WOLLASTON, Micrambe THOMSON, Sericoderus STEPHENS) and seven species Homoeodera pumilio WOLLASTON, 1877 (Anthribidae), Sericoderus sp. (Corylophidae), Micrambe gracilipes WOLLASTON, 1871 (Cryptophagidae), Cryptolestes ferrugineus (STEPHENS, 1831) (Laemophloeidae), Cartodere ? constricta (GYLLENHAL, -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Bugoni 2008 Phd Thesis

ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS AT SEA OFF BRAZIL Leandro Bugoni Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, at the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow. July 2008 DECLARATION I declare that the work described in this thesis has been conducted independently by myself under he supervision of Professor Robert W. Furness, except where specifically acknowledged, and has not been submitted for any other degree. This study was carried out according to permits No. 0128931BR, No. 203/2006, No. 02001.005981/2005, No. 023/2006, No. 040/2006 and No. 1282/1, all granted by the Brazilian Environmental Agency (IBAMA), and International Animal Health Certificate No. 0975-06, issued by the Brazilian Government. The Scottish Executive - Rural Affairs Directorate provided the permit POAO 2007/91 to import samples into Scotland. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was very lucky in having Prof. Bob Furness as my supervisor. He has been very supportive since before I had arrived in Glasgow, greatly encouraged me in new initiatives I constantly brought him (and still bring), gave me the freedom I needed and reviewed chapters astonishingly fast. It was a very productive professional relationship for which I express my gratitude. Thanks are also due to Rona McGill who did a great job in analyzing stable isotopes and teaching me about mass spectrometry and isotopes. Kate Griffiths was superb in sexing birds and explaining molecular methods again and again. Many people contributed to the original project with comments, suggestions for the chapters, providing samples or unpublished information, identifyiyng fish and squids, reviewing parts of the thesis or helping in analysing samples or data. -

UK Overseas Territories

INFORMATION PAPER United Kingdom Overseas Territories - Toponymic Information United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), also known as British Overseas Territories (BOTs), have constitutional and historical links with the United Kingdom, but do not form part of the United Kingdom itself. The Queen is the Head of State of all the UKOTs, and she is represented by a Governor or Commissioner (apart from the UK Sovereign Base Areas that are administered by MOD). Each Territory has its own Constitution, its own Government and its own local laws. The 14 territories are: Anguilla; Bermuda; British Antarctic Territory (BAT); British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT); British Virgin Islands; Cayman Islands; Falkland Islands; Gibraltar; Montserrat; Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands; Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands; Turks and Caicos Islands; UK Sovereign Base Areas. PCGN recommend the term ‘British Overseas Territory Capital’ for the administrative centres of UKOTs. Production of mapping over the UKOTs does not take place systematically in the UK. Maps produced by the relevant territory, preferably by official bodies such as the local government or tourism authority, should be used for current geographical names. National government websites could also be used as an additional reference. Additionally, FCDO and MOD briefing maps may be used as a source for names in UKOTs. See the FCDO White Paper for more information about the UKOTs. ANGUILLA The territory, situated in the Caribbean, consists of the main island of Anguilla plus some smaller, mostly uninhabited islands. It is separated from the island of Saint Martin (split between Saint-Martin (France) and Sint Maarten (Netherlands)), 17km to the south, by the Anguilla Channel. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Petrelsrefs V1.1.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2017 & 2018 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Killian Mullarney and Tom Shevlin (www.irishbirds.ie) for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.1 (August 2017). Cover Main image: Bulwer’s Petrel. At sea off Madeira, North Atlantic. 14th May 2012. Picture by Killian Mullarney. Vignette: Northern Fulmar. Great Saltee Island, Co. Wexford, Ireland. 5th May 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. Antarctic Petrel [Thalassoica antarctica] 12 Beck's Petrel [Pseudobulweria becki] 18 Blue Petrel [Halobaena caerulea] 15 Bulwer's Petrel [Bulweria bulweri] 24 Cape Petrel [Daption capense] 13 Fiji Petrel [Pseudobulweria macgillivrayi] 19 Fulmar [Fulmarus glacialis] 8 Giant Petrels [Macronectes giganteus & halli] 4 Grey Petrel [Procellaria cinerea] 19 Jouanin's Petrel [Bulweria fallax] 27 Kerguelen Petrel [Aphrodroma brevirostris] 16 Mascarene Petrel [Pseudobulweria aterrima] 17 Parkinson’s Petrel [Procellaria parkinsoni] 23 Southern Fulmar [Fulmarus glacialoides] 11 Spectacled Petrel [Procellaria conspicillata] 22 Snow Petrel [Pagodroma nivea] 14 Tahiti Petrel [Pseudobulweria rostrata] 18 Westland Petrel [Procellaria westlandica] 23 White-chinned Petrel [Procellaria aequinoctialis] 20 1 Relevant Publications Beaman, M. -

Threatened Species PROGRAMME Threatened Species: a Guide to Red Lists and Their Use in Conservation LIST of ABBREVIATIONS

Threatened Species PROGRAMME Threatened Species: A guide to Red Lists and their use in conservation LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AOO Area of Occupancy BMP Biodiversity Management Plan CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species DAFF Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EOO Extent of Occurrence IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature NEMA National Environmental Management Act NEMBA National Environmental Management Biodiversity Act NGO Non-governmental Organization NSBA National Spatial Biodiversity Assessment PVA Population Viability Analysis SANBI South African National Biodiversity Institute SANSA South African National Survey of Arachnida SIBIS SANBI's Integrated Biodiversity Information System SRLI Sampled Red List Index SSC Species Survival Commission TSP Threatened Species Programme Threatened Species: A guide to Red Lists and their use in conservation OVERVIEW The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List is a world standard for evaluating the conservation status of plant and animal species. The IUCN Red List, which determines the risks of extinction to species, plays an important role in guiding conservation activities of governments, NGOs and scientific institutions, and is recognized worldwide for its objective approach. In order to produce the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™, the IUCN Species Programme, working together with the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and members of IUCN, draw on and mobilize a network of partner organizations and scientists worldwide. One such partner organization is the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), who, through the Threatened Species Programme (TSP), contributes information on the conservation status and biology of threatened species in southern Africa. -

Tristan Da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha Biodiversity Action Plan Enquiries relating to this plan: Simon Glass Conservation Officer Tristan [email protected] James Glass Head of Tristan Natural Resources Department Tristan [email protected] Sarah Sanders Country Programmes Manager UK Overseas Territories RSPB [email protected] Cover photograph: Atlantic Yellow-nosed albatross on Nightingale Island with Tristan in the background All photos by: Paul Tyler, Alison Rothwell, Erica Sommer and James Glass Foreword by Lewis Glass Acting Administrator, Tristan da Cunha From the moment Tristão d’Acunha first sighted the islands in 1506, Tristan da Cunha has been recognised as a unique place, with an assemblage of wildlife found nowhere else on the globe. Our very way of life on Tristan has always been dependant on the sustainable harvest of the natural resources of the island, and careful management has protected this resource for future generations. For the first time the Tristan islanders are now fully involved in the conservation of our unique natural heritage, not only for the economy of the islands, but also for the enlightenment and enjoyment of current and future generations. This plan will guide and encourage our efforts to protect our unique islands. Lewis Glass Acting Administrator Tristan da Cunha October 2005 2 By Mike Hentley Administrator, Tristan da Cunha Residents on Tristan, the world’s most isolated island community, well understand the need to live in harmony with nature. Their livelihoods depend on using natural resources wisely, and they take seriously their responsibilities for preserving a healthy environment on Tristan and it’s neighbouring islands. -

Rep Octs South Atlantic 2007.Pdf 732.41 KB

European Commission EuropeAid Cooperation Office Framework contract Beneficiaries LOT 6 - Environment Country: Overseas Countries and Territories Project title: OCT Environmental Profiles Request for services no. 2006/12146 Final Report Part 2 - Detailed Report Section E - South Atlantic Region January 2007 Consulting Engineers and Planners A/S, Denmark PINSISI Consortium Partners PA Consulting Group, UK IIDMA, Spain ICON Institute, Germany Scanagri, Denmark NEPCon, Denmark INVESTprojekt NNC, Czech SOFRECO, France OVERSEAS COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE PART 2 - Detailed Report Section A - South Atlantic region This study was financed by the European Commission and executed by the Joint-Venture of NIRAS PINSISI Consortium partners. The opinions expressed are those of the consultants and do not represent any official view of the European Commission nor the Governments of any of the overseas countries and territories or associated member states of the European Union. Prepared by: Jonathan Pearse Helena Berends Page 2 / 74 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS USED ACAP Agreement on Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels ACOR Association Française pour les Récifs Coralliens ACS Association of Caribbean States AEPS Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy AFL Aruba guilders AI Ascension Island AIG Ascension Island Government AIWSA Ascension Island Works & Services Agency AMAP Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme ANG Anguilla ANRD Agricultural & Natural Resources Department AOSIS Alliance of Small Island States APEC Asia–Pacific -

UK Overseas Territories

Whale shark off St Helena Credit EMD August 2014 Newsletter: UK Overseas Territories The Darwin Initiative supports developing countries to conserve biodiversity and reduce poverty. The Darwin Initiative (funded by DEFRA, DFID and FCO), provides grants for projects working in developing countries and UK Overseas Territories (OTs). Projects support: • the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) • the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) • the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) • the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) darwininitiative.org.uk @Darwin_Defra Facebook page LinkedIn Alumni page Dr Tom Hart and Dr Ben Collen in a colony of king penguin (Aptenodytes) Credit IoZ Contents A word from Defra Page 3 Newsletter contacts Page 4 The Darwin Expert Committee - an insider’s perspective Page 5 Protecting St Helena Island’s marine biodiversity Page 7 Coral nursery project in Little Cayman: enhancing resilience and natural Page 8 capacity of coral reefs in the UKOTs Multi-disciplinary research and international collaboration to rescue the Caicos Page 9 pine forests Bermuda Invasive Lionfish Control Initiative Page 10 Bugs on the Brink– Invertebrate conservation on St Helena Page 11 British Virgin Islands Marine Protected Areas & hydrographic survey capacity Page 12 building Marine monitoring around the world’s most remote inhabited island Page 13 Ensuring engagement in Cayman’s enhanced marine protected area system Page 14 Initial findings of underwater video of reef fishes at Pitcairn Page 15 Darwin Initiative to strengthen the World’s largest Marine Protected Area, Page 16 Chagos Archipelago Clown fish and anemone Credit J Turner A word from the Darwin Initiative UKOTs Edition of the newsletter these applications and will have the hard job of recommending who gets funding. -

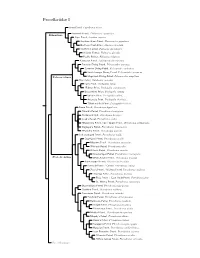

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma