Cesar Cornejo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE for IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 12, 2016

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 12, 2016 Contact: Laura Carpenter (907) 929-9227 [email protected] High-resolution images available at the museum’s online media room, www.anchoragemuseum.org/media Artistic and insider look at the North reveals complex and changing place ‘View From Up Here’ on view May 6 through Oct. 2 at the Anchorage Museum ANCHORAGE, Alaska – Home to four million people, the Arctic has also long drawn explorers, artists and other investigators, and that fascination with the North continues today. “View From Up Here: The Arctic at the Center of the World” is an international contemporary art exhibition at the Anchorage Museum that highlights contemporary investigations into the Arctic through the perspective of artists. The exhibition conveys a complexity of place and people through film, photographs, installations and sculptures that highlight Arctic landscape and culture. “View From Up Here” also offers glimpses into the future of the Arctic within the context of great environmental and cultural change. The artworks in the exhibition offer insights into the North, presenting the North from a broader perspective. Participating artists range from Indigenous artists from Alaska offering an insider view of the North to international contemporary artists who have visited and studied the Arctic. The exhibition will have components throughout the museum, from formal galleries to an informal "living room" that offers gathering space for investigation and conversation, as well as installations in common spaces and outdoors. It is accompanied by public programs, including performances, in the museum and out in the community. A corresponding publication supports examination of the North beyond black-and-white perspectives. -

Exhibition Booklet

EXTRACTED Mary Mattingly | Otobong Nkanga | Claire Pentecost | David Zink Yi | Marina Zurkow August 22–December 10, 2016, USF Contemporary Art Museum CURATOR’S INTRODUCTION Megan Voeller In 2000, Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen organize us, and it is, finally, a way to understand our set off a chain reaction when he called for our current geological organization and, inevitably, to reorganize ourselves,” writes epoch to be labeled “the Anthropocene” as a reflection of Alva Noë in his book Strange Tools: Art and Human Nature. changes wrought by humans on the environment. The concept In the Anthropocene, we need the strange tools of art more of christening a new epoch during our lifetimes—the most than ever. recent, the Holocene, has lasted for 11,700 years since the last ice age—is mind-bending. Rarely is such obscure bureaucratic In Extracted, Mary Mattingly models the perspective of business freighted with such outsized existential consequence. a critical participant in global capitalism. She binds her Appropriately, debate about the concept has been rigorous personal possessions—books, clothing, even electronics within the scientific community at large and the Anthropocene and furniture—into sculptural bundles that invite viewers to Working Group of the International Commission on Stratigraphy, consider everyday objects, their lives and their entwinement which is expected to issue a proposal on how the term should with ours. Mattingly incorporates these sculptures into be used scientifically (namely, whether it should indicate a new performances and photographs that draw connections epoch or a lesser “age,” and when the period began) in 2016. between our belongings and the materials and labor used to produce them. -

Sustainability

Queens Museum 2018 SUSTAINABILITY Open Engagement Table of Contents A note about this program: This document, just like the conference itself, is a Front and back cover: 4 Director’s Welcome Jökulsárlón Glacial Lagoon, Iceland, 2017 labor of love split between a tiny part-time staff and a Program Design: 5 Acknowledgments few interns. Please be kind and gentle with us if Lauren Meranda, Andrés Alejandro Chavez, 6 Curatorial Statement you see an error, omission, typo, or any other human Kate Heard mistake while reading this document. 7 OE 2018 Team 8 Locations Social Media 10 Queens Info Follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook Schedule @openengagement 12 Overviews Share your posts from this year with #OE2018 18 Featured Presentations #OpenEngagement 19 Pre-Conference Find further details at 20 Open House www.openengagement.info 23 Saturday Parallel Sessions 26 Conversational Dinners OEHQ 28 Sunday Parallel Sessions OEHQ (information and registration) is our conference 31 Parties & Projects hub! OEHQ is the place for the most up-to-date 33 Open Platform information about the conference throughout the weekend, including any schedule or location changes. 36 Trainings Bronx Museum of the Arts Friday, May 11th: 6:00pm - 7:30pm 37 Featured Presenters 38 Contributor Bios Werwaiss Family Gallery, 2nd Floor, Queens Museum Saturday, May 12th: 9:00am – 5:00pm 42 Schedule at a Glance Sunday, May 13th: 9:00am – 4:00pm 2 3 Director’s Welcome Acknowledgements It is 6:12am and I have been in bed thinking about writing this I wish I could talk to Ted about where we are now. -

Catalog for Overview Effect

2 3 overview effect. Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade project and curatorial direction: October 2nd, 2020 – September 20th, 2021 Blanca de la Torre and Zoran Erić overview effect. The term Overview Effect was coined by Frank White in 1987 to describe the cognitive shift reported by a number of astronauts on having looked back from Space at their home planet Earth. The question is, do we need such a distant point of view of the planet we occupy, as a “crew of the Spaceship Earth” to use Buckminster Fuller’s 4 metaphor, to realize that this “spaceship” is slowly running out of “fuel” and that the 5 crew is in need of “oxygen”? This project seeks to address the issue of the environmental justice that can only be approached through an analysis of the inseparable links between climate change and other forms of injustice related to gender, race, corporate imperialism, indigenous sovereignty, and the importance of decolonising and de-anthropocentrizing the planet in order to reshape an inclusive mindset akin to a multispecies world. The curatorial strategy will explore alternative exhibition-making formats and responds to the rhizomatic idea of ECO_LABS where six realms represent distinct sub-themes, all of them interconnected: 1 — GENDER, RACE AND THE COLONIAL TRACE 2 — WATERTOPIAS 3 — THERE IS NO EDGE! (LAND ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMATICS) 4 — LEARNING FROM INDIGENISM 5 — BEYOND ANTHROPOCENE (POST-HUMANISM, ANIMISM AND MULTISPECIES WORLD) 6 — BACK TO THE FUTURE (FUTUROLOGY AND SPECULATIVE REALISM) Each ECO_LAB will take on the role of a think-thank for art and knowledge production related to the sub-themes we derived from the overall concept, within the whole methodological approach to the development of the exhibition. -

DAVID BROOKS Born 1975 – Brazil, Indiana EDUCATION 2009 MFA

DAVID BROOKS Born 1975 – Brazil, Indiana EDUCATION 2009 MFA, Columbia University, School of the Arts, New York 2000 BFA, The Cooper Union, School of Art, New York 1998 Städelschule, Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Frankfurt am Main, Germany SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 The Great Bird Blind Debate, (with Mark Dion), Planting Fields Foundation, Oyster Bay, NY (book) 2019 Umwelts 2019 (As the Crow Flies), Cheekwood Museum of Art, Nashville, TN 2018 Rock, Mosquito and Hummingbird (A Prehistory of Governors Island), Season Two, commissioned by the Trust for Governors Island, NYC (book) 2017 Continuous Service Altered Daily, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE Case Study: Weld County, Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, Fort Collins, CO Rock, Mosquito and Hummingbird (A Prehistory of Governors Island), Preview, commissioned by the Trust for Governors Island, NYC 2016 Continuous Service Altered Daily, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT (catalog) 2015 A Day in The Life of The Coral (as seen at Brewster Reef), Fringe Projects, Museum Park, Miami, FL 2014 Repositioned Core, Visual Arts Center, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX Lonely Loricariidae, Art Basel Statements, Basel, Switzerland 2013 A Proverbial Machine in the Garden, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, NY Gap Ecology (Three Still Lives with Cherry Picker and Palms, Socrates Sculpture Park, with "Marfa Dialogues/NY" walk following the Florence city boundary line (by Daniel Maier-Reimer), CLAGES, Cologne, Germany 2012 Notes On Structure [imbroglios, heaps and myopias], American Contemporary, New York Picnic Grove, Cass Sculpture Foundation, West Sussex, UK Sketch of a Blue Whale (enlarged to scale 23m, 154 tons), Cass Sculpture Foundation, West Sussex, UK 2011 Desert Rooftops, Art Production Fund, Last Lot, New York 2010 Terra Firma, Centro Medico Santagostino, Milan, Italy Trophic Pyramids and their Producers, Armory, New York 2009 Naturae Vulgaris, Museum 52, New York 2008 Quick Millions, Museum 52, New York SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 Cinque Mostre. -

Our 2009 WATERPOD™ PRESS RELEASE Is Available to Download

INTRODUCTION While living on and navigating an inland deck barge surmounted by futuristic architectural structures in the resurgent waters of NYC, 5 International artists will live, work, and hold events in order to further the public-centered artistic, ecological, scientific, and cultural richness of New York's 5 boroughs and the surrounding waterways. Water, and how we manage our water resources, is going to define this Century. Designed with the rising tides in mind, Waterpod™ seeks to address a future of warming driven human displacement, compounded by an influx of climate refugees in need of insightful technology created with attainable materials. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION Waterpod™ is a floating sculptural living structure designed as a new eco-habitat for the global warming epoch and for local, national, and international awareness of water. It will launch in New York in summer of 2009, navigate the East and Hudson Rivers, stopping at each of the five boroughs. Waterpod™ demonstrates future pathways for nomadic/mobile structures and water-based communities, docked and roaming. Built from recycled materials and eco-friendly products, Waterpod™ is structured as a space for community and artist activity, eco-initiatives and living space. As a sustainable, navigable living space, Waterpod™ showcases the critical importance of the environment and serves as a model for new living technologies. Waterpod™ strives to educate and motivate the public with environmental awareness and a "you can do it yourself" attitude. Waterpod™ is structured with space for: (i) community and artistic activity; (ii) eco- initiatives including food grown with collected rainwater, gray water recycling with energy provided from environmental and human sources; and (iii) living. -

Performing for Cyclops, an Exhibition of Contemporary Video Art, Opens at the Pitch Project July 12, 2014 from 59PM

Performing for Cyclops, an Exhibition of Contemporary Video Art, Opens at The Pitch Project July 12, 2014 from 59PM. The Pitch Project (706 S. 5th St., Milwaukee, WI 53204, USA), is proud to present Performing for Cyclops, a group exhibition of contemporary video art. Five internationally exhibited artists, Jonathan Gitelson, William Lamson, Julie Lequin, Mary Mattingly, and Kambui Olujimi, will be featured in the show. Work ranges in scale from room size projection to intimate encounters with personalsized screens. Many of the works center on the artist performing for the camera using humor and ingenuity to explore narratives from the commonplace routine to playful and absurd rituals. The performances in this exhibition blur the line between the fictional and personal, inviting perspectives on the how the human force contends with courageousness, woe, and error in real time. In both of her videos, Lequin constructs personas and language to investigate her art practice. Gitelson’s wry work documents/performs his last cigarette accompanied by an original banjo score by Nils d’ Aularie. Lamson’s videos push at machismo while shooting at balloons or hunting sneakers hanging from Brooklyn electrical wires. Mattingly’s sculptural boulders of excess stimulate thoughts about consumer culture and mobility in the global economy. Kambui Olujimi’s 2014 film “Not Now Nor Then” will be featured in The Pitch Project Media Gallery. His film inspired from the missing Malaysian Flight MH 370 asks “If our perceptions of total connectivity are wrong and the world is not in fact flat, then I ask you, what is on the other side?” Performing for Cyclops will run July 12 October 12, 2014. -

Mary Mattingly. Bottom: Mary Mattingly

Top: Mary Mattingly. The Waterpod , 2009. Photo: Mary Mattingly. Bottom: Mary Mattingly. The Waterpod , 2009. Concrete Plant Park, the Bronx, New York. Photos: Eva Díaz. 80 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00020 by guest on 27 September 2021 Dome Culture in the Twenty-first Century EVA DÍAZ In September 2009 I spent a night on the Waterpod , a river barge project undertaken by artist Mary Mattingly that made various stops around the New York City harbor that summer. When Sara Reisman and I—the pod’s two overnight guests that evening—arrived, its half-dozen residents had secured permission only a day or two before to be towed to the newly opened Concrete Plant Park in the Bronx. 1 We embarked late on a Friday night, greeted on the main deck by a dinner for eight prepared from produce and herbs grown in the on- board garden. The following morning Alison Ward, one of the ship’s full-timers and the master of the ship’s mess, scrambled eggs freshly laid by chickens kept on the barge, cooking like a frontierswoman in a cast-iron skillet over an oil drum repurposed as a stove, all the while stoking a temperamental fire belching acrid clouds of smoke. Then Sara and I, with resident Ian Daniel’s coaxing, pushed off in one of the pod’s kayaks for a tour of the Bronx River (a waterway I never knew existed), heading toward LaGuardia Airport. Afterward we stuck around the pod for part of a workshop on worm composting by artist Tattfoo Tan, who rolled on board with extensive gear—soil samples, worms, and whatnot—wearing a park ranger getup tessellated with patches proclaiming him a “Citizen Pruner” and “Certified Master Composter,” among other seemingly ersatz designations. -

Annual Report 2013

Cover Back Spine: (TBA) Front PMS 1505 Knock out Annual Report 2013 LETTER FROM THE MAYOR, FIRST DEPUTY MAYOR & COMMISSIONER 4 PART I: FISCAL YEAR 2013 INTRODUCTION 8 PROGRAM SERVICES 15 CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS GROUP 18 CAPITAL PROJECTS 22 GROUNDBREAKINGS & RIBBON CUTTINGS 24 31st ANNUAL AWARDS FOR EXCELLENCE IN DESIGN RECIPIENTS 26 PERCENT FOR ART 28 COMPLETED PROJECTS & NEW COMMISSIONS 29 COMMUNITY ARTS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 30 MATERIALS FOR THE ARTS 32 SPECIAL INITIATIVES 34 CULTURAL AFTER-SCHOOL ADVENTURES (CASA) 34 SENIORS PARTNERING WITH ARTISTS CITYWIDE (SPARC) 35 RESEARCH & TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE 36 TEMPORARY PUBLIC ART INSTALLATIONS & PERFORMANCES 38 CULTURAL AFFAIRS ADVISORY COMMISSION 42 MAYOR’S AWARDS FOR ARTS AND CULTURE 43 NYC LITERARY HONORS 44 PART II: AGENCY PORTFOLIO, FY13 CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT FUND AWARD RECIPIENTS 48 CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT FUND PANELISTS 53 NEW CAPITAL ALLOCATIONS: CONSTRUCTION & EQUIPMENT PURCHASES 54 SENIORS PARTNERING WITH ARTISTS CITYWIDE (SPARC) RESIDENCIES 57 CULTURAL AFTER-SCHOOL ADVENTURES (CASA) AWARD RECIPIENTS 58 MATERIALS FOR THE ARTS RECIPIENTS OF DONATED GOODS 60 DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS STAFF 74 PHOTO CREDITS 76 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 77 4 Letter from The Mayor, First Deputy Mayor & Commissioner Culture is one of New York City’s signature industries, Tobacco Warehouse, Theatre for a New Audience, and present in every neighborhood of all five boroughs. It Urban Glass, as well as Culture Shed and the Whitney supports our economic vitality, generates excitement, Museum of American Art on Manhattan’s West Side. and enhances quality of life, in turn making New York The City also maintained its record-high funding levels City a world-class destination. That’s why we are proud for arts and culture in FY13, the results of which can be to be the nation’s largest single arts funder, supporting seen in the exceptional work produced by the cultural programming, operations, and construction projects at sector. -

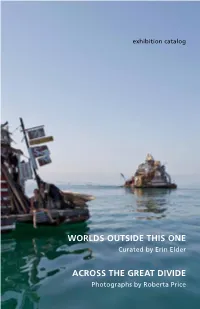

WORLDS OUTSIDE THIS ONE Across the GREAT Divide

exhibition catalog WORLDS OUTSIDE THIS ONE Curated by Erin Elder ACross the Great DIVide Photographs by Roberta Price WORLDS OUTSIDE THIS ONE Curated by Erin Elder ACross the Great DIVide Photographs by Roberta Price June 4 – August 27, 2011 In conjunction with the unCOMMON GROUND collaboration organized by 516 ARTS with the Alvarado Urban Farm 516 Central Avenue SW Downtown Albuquerque, New Mexico www.516arts.org 516 ARTS is an independent, nonprofit arts and education organization, with a museum-style gallery in Downtown Albuquerque. We offer programs that inspire curiosity, dialogue, risk-taking and creative experimentation, showcasing a mix of established, emerging, local, national and international artists from a variety of cultural backgrounds. Our mission is to forge connections between art and audiences, and our vision is to be an active partner in developing the cultural landscape of Albuquerque CONTENTS and New Mexico. Our values are inquiry, diversity, collaboration and accessibility. Introduction 4 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY BOARD by Suzanne Sbarge Arturo Sandoval, Chair Frieda Arth Suzanne Sbarge, President/Founder Hakim Bellamy David Vogel, Vice President Michael Berman Kathryn Kaminsky, Secretary Sherri Brueggemann WORLDS OUTSIDE THIS ONE: Joni Thompson, Treasurer Christopher Burmeister Dr. Marta Weber, Fundraising Chair David Campbell Fort-Building or the Path to Radical Social Change 5 Clint Wells Andrew Connors by Erin Elder Debi Dodge STAFF & CONSULTANTS Miguel Gandert Lisa Gill Artists 11 Suzanne Sbarge, Executive -

Flock House Project Consists of Three Sculptural Ecosys- Tems and Modular Habitats Choreographed Throughout Urban Centers

MaryFLOCK Mattingly HOUSE Contents: Introduction Design Prototypes Permits Locations and Inhabitants A Rooftop in Brooklyn Eyebeam Center for Art and Technology Clocktower Gallery Battery Park, Lower Manhattan Flushing Meadows Corona Park, Queens Pearl Street Triangle, DUMBO Lower East Side, Chinatown 125 Maiden Lane, Lower Manhattan Van Cortlandt Park, the Bronx The Bronx Museum Parking Lot, the Bronx Collaborators and Sponsors Introduction The Flock House Project consists of three sculptural ecosys- tems and modular habitats choreographed throughout urban centers. During the spring of 2011 and the summer of 2012, Flock Houses were located in New York City, with sites includ- ing: Battery Park in Lower Manhattan; an atrium of an office building in Manhattan; a public square in DUMBO, Brooklyn; Flushing Meadows Corona Park, Queens; a parking lot in the Bronx; and a rooftop in Downtown Brooklyn. As I have witnessed urban populations faced with environ- Distilled data-visualization of migration patterns of mental, political, and economic instability, I propose the Flock people, 2011 House Project as a bridge across sociopolitical boundaries of perimeter, property, and polity. Flock Houses suggest migra- tory structures as part of a city’s ecology, and their shape and form visualize patterns of current global human migration and immigration. Tested by temporary residents and fabricated with open source plans, the units were built using reclaimed materials acquired through local barter networks. They promote wider adoption of natural systems such as rainwater capture, inner- city agriculture, and solar energy technologies. The building and installation methods for these living systems were made in collaboration with Appropedia.org, a collective group dedi- cated to Appropriate Technologies. -

City of Syracuse Public Art Application

Application #: SPAC 16-01 CITY OF SYRACUSE PUBLIC ART APPLICATION All applications for the installation of public art will be evaluated based on the seven (7) criteria enumerated below. It is understood that some criteria will have more relevance than others depending on the proposed artwork. This will be taken into account and the criteria weighted accordingly. ■ Artistic merit and quality, as substantiated by an artist’s past history of exhibitions or sales, awards or other recognition, or an outstanding first work, as well as the inherent quality in terms of timelessness of vision, design, aesthetics and excellence; ■ Intentionality of the artist, concerning the meaning and proposed or desired effect of the work as Public Art upon the viewing public, as rationalized and elaborated upon in the project description; ■ Local significance, creating a sense of excitement in public spaces and presenting fresh ways of seeing the community and city reflected; ■ Representation of styles and tastes within the public art collection, acknowledging existing works in the public art collection and striving for diversity of style, scale and media; ■ Safety and durability, including the ability of the artwork to withstand weather conditions, as well as structural and surface integrity; ■ Unrestricted public viewing, primarily the opportunity for public access, but also suitability for public participation, social and political attitudes, and functional considerations; and ■ Installation and maintenance of the work, from practicality of fabrication and