Downward Trends in the Prevalence of Childhood Overweight in the Setting of 12-Year School- and Community-Based Programmes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs

PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS RECUEIL n° 23 du 5 avril 2019 Le Recueil des Actes Administratifs sous sa forme intégrale est consultable en Préfecture, dans les Sous-Préfectures, ainsi que sur le site Internet de la Préfecture (www.pas-de-calais.gouv.fr) rue Ferdinand BUISSON - 62020 ARRAS CEDEX 9 tél. 03.21.21.20.00 fax 03.21.55.30.30 PREFECTURE DU PAS-DE-CALAIS.......................................................................................3 - Arrêté préfectoral accordant la médaille d’honneur communale, départementale et régionale..........................................3 - Arrêté préfectoral accordant la médaille d’honneur agricole............................................................................................53 MINISTERE DE LA JUSTICE-DIRECTION INTERREGIONALE DES SERVICES PENITENTIAIRES...................................................................................................................61 Maison d’arrêt d’Arras........................................................................................................................................................61 Décision du 2 avril 2019 portant délégation de signature...................................................................................................61 DIRECCTE HAUTS-DE-FRANCE..........................................................................................62 - Modifications apportées à la décision du 30 novembre 2018 portant affectation des agents de contrôle dans les unités de contrôle et organisation -

Annuaire Médiation Familiale 2016.Pdf

Qu’est-ceQu que la médiation familiale ? La médiation familiale est un temps d’écoute, d’échanges et de négociation qui vous permet : • d’aborder les problèmes liés à un conflit familial, • de prendre en compte de manière très concrète les besoins de chacun, notamment ceux des enfants, avec un tiers qualifié et impartial : le médiateur familial. Son rôle est de rétablir la communication et de créer un climat de confiance propice à la recherche d’accords entre les personnes. Qui est concerné ? La médiation familiale, pour quoi ? • Vous êtes en couple ou parents en situation de rupture, Pour vous permettre : séparation, divorce, • d’établir une communication constructive, • Vous êtes jeunes adultes en rupture de liens avec votre • d’identifier au mieux la source du conflit, famille, • d’organiser vos droits et devoirs de parents, de grands • Vous êtes grands parents et souhaitez garder des liens parents, avec vos petits enfants, • d’aborder les questions financières. • Vous devez régler une succession conflictuelle… Qui est le médiateur familial ? Quand s’adresser au médiateur ? Le médiateur familial est un professionnel qualifié. Vous pouvez faire appel à un médiateur familial : Doté de compétences en psychologie et en droit, il est • Avant ou pendant la séparation : « faire le point » et notamment formé à l’écoute et à la négociation entre préparer ses conséquences, les personnes. Il respecte des principes déontologiques • Après la séparation : lorsque les décisions prises ne et observe une stricte confidentialité. Il ne prend parti correspondent plus à vos besoins actuels et ceux de pour personne et ne vous juge pas. Son rôle est de vous vos enfants, aider à trouver une solution concrète à votre conflit ou • A tout moment d’un conflit familial susceptible d’en- à votre situation. -

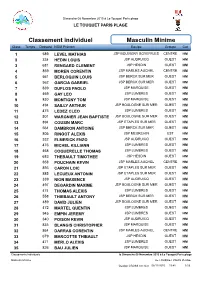

Classement Individuel Masculin Minime

Dimanche 11 Octobre 2015 à LAVENTIE LAVENTIE Classement individuel Masculin Minime Class Temps Dossard NOM Prénom Equipe Groupe Cat 1 589 LEVEL MATHIAS JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES CENTRE HM 2 365 PEREL LUCAS JSP SAINT VENANT CENTRE HM 3 501 WARGNIER JEAN BAPTISTE JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 4 494 SAILLY ARTHUR JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 5 629 GUEANT MATTEO JSP HENIN CARVIN EST HM 6 643 RASSON ALESSANDRO JSP HENIN CARVIN EST HM 7 468 COQUERELLE THOMAS JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 8 475 LEDEZ CLEO JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 9 805 RINGOT ALEXIS JSP MEURCHIN EST HM 10 640 DEVILLERS FABIEN JSP HENIN CARVIN EST HM 11 297 SOUILLART LEO JSP BRUAY HOUDAIN CENTRE HM 12 323 BLONDEL LOUIS JSP WINGLES EST HM 13 474 THOMAS ALEXIS JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 14 315 OURDOUILLIE LOUIS JSP WINGLES EST HM 15 477 LAURENCE DAVID JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 16 576 DUPLESSY THEO JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES CENTRE HM 17 363 DIMPRE AXEL JSP SAINT VENANT CENTRE HM 18 364 WILLEMS NICOLAS JSP SAINT VENANT CENTRE HM 19 717 PETIPREZ PAUL JSP LILLERS CENTRE HM 20 582 WISATZKE ILARIO JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES CENTRE HM 21 476 MICHEL KILLIANN JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 22 628 GENSE LEO JSP HENIN CARVIN EST HM 23 880 PRUVOST LUCAS JSP WINGLES EST HM 24 579 TEMPEZ THOMAS JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES CENTRE HM 25 820 GUILLEMANT TOM JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES CENTRE HM 26 716 MENTEAU CLEMENT JSP LILLERS CENTRE HM 27 469 GAY LEO JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 28 314 PETIT ALEXIS JSP WINGLES EST HM 29 471 MERLO ALEXIS JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 30 497 DEGARDIN MAXIME JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 31 584 BOULON VIANNEY JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES -

RÉFÉRENDUM DE 1958 Constitution De La Vème République Préfecture

RÉFÉRENDUMS - 1 RÉFÉRENDUM DE 1958 Constitution de la V ème République Préfecture. Cabinet du préfet • Déroulement de la campagne électorale 1W45524/2 Prévisions des résultats : rapports des sous-préfets et du préfet au ministre de l’Intérieur. 1W45524/3 Propagande communiste : rapports des Renseignements généraux. 1W45524/4 Propagande socialiste : rapports des Renseignements généraux. 1W45524/7 Note sur la présence de ressortissants marocains sur certaines listes électorales. • Résultats 1W45524/6 Déroulement du référendum : rapport du préfet au ministre de l’Intérieur. 1W45524/5 Suivi des résultats. Sous-préfecture de Lens 1724W41/1 Activité politique et presse : rapports des Renseignements généraux antérieurs et postérieurs à la consultation. Coupures de presse. RÉFÉRENDUMS - 2 RÉFÉRENDUM DE 1961 Autodétermination de l’Algérie Préfecture. Cabinet du préfet • Déroulement de la campagne électorale 1W45524/8 Organisation matérielle du scrutin : circulaire ministérielle. Allocution prononcée le 20 décembre 1960 par le général de Gaulle. 1W45524/8 Prévisions : rapport du 23 décembre 1960. 1W45524/8 Position des organisations politiques : rapport des Renseignements généraux. • Résultats 1W45524/8 Rapport post-électoral du préfet au ministre de l’Intérieur. Sous-préfecture de Lens 1724W41/2 Affiche de l’allocution du général de Gaulle. Affiche reproduisant l’arrêté de convocation des électeurs. 1724W41/3 Activité politique et presse : rapports des Renseignements généraux. Coupures de presse et tracts de propagande. RÉFÉRENDUMS - 3 RÉFÉRENDUM DU 8 AVRIL 1962 Accords d’Évian Préfecture. Cabinet du préfet • Instructions 1W45528/1 Instructions ministérielles et préfectorales. • Résultats 1W45528/3 Prévisions sur les résultats, exposé et appréciations sur les résultats du référendum : rapport du préfet au ministre de l’Intérieur. 1W45528/2 Résultats par circonscription, par canton et par commune. -

Pharmacies HDF Enregistrées Vaccination

Département Commune Dénomination de la pharmacie Adresse 02 - Aisne AMBLENY PHARMACIE CORROYER-CHAUVIN ET MARLIÈRE-FOLLET 5 Rue DANTALE 02 - Aisne ANIZY-LE-GRAND PHARMACIE HAMM 4 Place Rochechouard 02 - Aisne ATHIES-SOUS-LAON PHARMACIE MAES 64 TER Rue DES ÉCOLES 02 - Aisne AULNOIS-SOUS-LAON PHARMACIE BLANCHE 10 Rue DE CHAMBRY 02 - Aisne BEAUREVOIR PHARMACIE RODRIGUES 2 Place CHARLES DE GAULLE 02 - Aisne BEAURIEUX PHARMACIE GRUMELART-BOUVIER 4 D Rue ernest rousselot 02 - Aisne BEAUTOR PHARMACIE SEIGNEZ 54 Rue DE TERGNIER 02 - Aisne BELLEU PHARMACIE DELHORBE-LE ROUX RES DE LA PRAIRIE 5 Rue LEON BLUM 02 - Aisne BELLEU PHARMACIE MARLIERE 67 Avenue CHATEAU THIERRY 02 - Aisne BLERANCOURT PHARMACIE BLEUSE-BOUTAINE 8 Place DE L'HOTEL DE VILLE 02 - Aisne BOHAIN-EN-VERMANDOIS PHARMACIE GUYOT-RACOUSSOT 28 Rue FRANCIS DE PRESSENSÉ 02 - Aisne BOHAIN-EN-VERMANDOIS PHARMACIE IDEE Rue 33 RUE JEAN JAURÈS 02 - Aisne BOHAIN-EN-VERMANDOIS PHARMACIE LEVEAUX-DELANNOY 3 Place DU GENERAL DE GAULLE 02 - Aisne BOUE PHARMACIE CAMUT-CONNART 47 Rue DE LA GARE 02 - Aisne BOURG-ET-COMIN PHARMACIE CAILLIEZ 1 Place DU MARCHÉ 02 - Aisne BRAINE PHARMACIE DEREGNAUCOURT ET HAUTUS-DUPUIT 49 Place CHARLES DE GAULLE 02 - Aisne BRAINE PHARMACIE RAMPELBERG-LEMESTRE 68 Rue DU MARTROY 02 - Aisne BRUNEHAMEL PHARMACIE SARAZIN 14 Place DE MAI 1940 02 - Aisne BRUYERES-ET-MONTBERAULT PHARMACIE PICARD-CLOUX 2 Place DU GENERAL DE GAULLE 02 - Aisne BUCY-LE-LONG PHARMACIE GAILLARD Place DE LA MAIRIE 02 - Aisne BUIRONFOSSE PHARMACIE FOSSAERT 8 Rue DU 11 NOVEMBRE 02 - Aisne CHARLY-SUR-MARNE -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

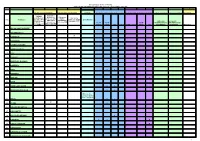

Classements Individuels Par Cate?

Dimanche 08 Novembre 2015 à Le Touquet Paris plage LE TOUQUET PARIS PLAGE Classement individuel Masculin Minime Class Temps Dossard NOM Prénom Equipe Groupe Cat 1 589 LEVEL MATHIAS JSP BOUVIGNY BOYEFFLES CENTRE HM 2 334 HEDIN LOUIS JSP AUDRUICQ OUEST HM 3 681 RENGARD CLEMENT JSP HESDIN OUEST HM 4 859 MOREN CORENTIN JSP MARLES AUCHEL CENTRE HM 5 561 BERLOQUIN LOUIS JSP BERCK SUR MER OUEST HM 6 562 GARCIA GABRIEL JSP BERCK SUR MER OUEST HM 7 839 DUFLOS PAOLO JSP MARQUISE OUEST HM 8 469 GAY LEO JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 9 830 MONTIGNY TOM JSP MARQUISE OUEST HM 10 494 SAILLY ARTHUR JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 11 475 LEDEZ CLEO JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 12 501 WARGNIER JEAN BAPTISTE JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 13 894 COUSIN MARC JSP ETAPLES SUR MER OUEST HM 14 564 DAMBRON ANTOINE JSP BERCK SUR MER OUEST HM 15 805 RINGOT ALEXIS JSP MEURCHIN EST HM 16 332 ELMERICK ENZO JSP AUDRUICQ OUEST HM 17 476 MICHEL KILLIANN JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 18 468 COQUERELLE THOMAS JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 19 683 THEBAULT TIMOTHEE JSP HESDIN OUEST HM 20 858 POUCHAIN KEVIN JSP MARLES AUCHEL CENTRE HM 21 893 CARON LOIC JSP ETAPLES SUR MER OUEST HM 22 885 LECUEUX ANTONIN JSP ETAPLES SUR MER OUEST HM 23 339 NION MAXENCE JSP AUDRUICQ OUEST HM 24 497 DEGARDIN MAXIME JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 25 474 THOMAS ALEXIS JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 26 558 THIEBAULT ANTONY JSP BERCK SUR MER OUEST HM 27 489 DAVID JULIEN JSP BOULOGNE SUR MER OUEST HM 28 472 MARTEL QUENTIN JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 29 945 EMPIN JEREMY JSP LUMBRES OUEST HM 30 340 POISON KEVIN JSP AUDRUICQ OUEST HM 31 835 BLANGIS CHRISTOPHER -

Les AFR Et ZFU En 2007

ARRONDISSEMENT D'ARRAS ZONAGE ET DELIBERATIONS DANS LES COLLECTIVITES LOCALES Jeunes Entrep AFR 2007/2013 PERMANENT AFR 2007/2008 TRANSITOIRE ZONAGE DELIBERATIONS AU NIVEAU DE L EPCI DELIBERATIONS AU NIVEAU COMMUNAL ZONES FRANCHES ZONES FRANCHES Innovantes Communes Communes éligibles éligibles en Communes partiellement Communes totalité aux aides éligibles Code Communes aux aides AFR éligibles en totalité ZFU-ZRU-ZRR AFR à taux partiellement à taux normal, aux aides AFR 1383 B (TF) 1466 A (TP) normal, non aux aides AFR non limitées aux 1464B- 1464B- 1464B- DELIBERTATIONS (DELIBERATIONS limitées aux PME PME création reprise 1465 1383 A 1464B-création reprise 1465 CONTRAIRES CONTRAIRES 1466 D (TP) 1 ABLAIN SAINT NAZAIRE 2 ABLAINZEVELLE X 3 ACHEVILLE 4 ACHICOURT 5 ACHIET LE GRAND 6 ACHIET LE PETIT 7 ACQ 9 ADINFER 11 AGNEZ LES DUISANS 12 AGNIERES 13 AGNY X X 27 AMBRINES 30 AMPLIER X 36 ANVIN 37 ANZIN SAINT AUBIN X X X 39 ARLEUX EN GOHELLE X X ZRU-(Quartiers : rés. St-Pol, Blancs Monts, Baudimont) 41 ARRAS X X X 42 ATHIES X X 45 AUBIGNY EN ARTOIS 47 AUBROMETZ 50 AUCHY LES HESDIN X 58 AUMERVAL X X X 60 AUXI LE CHATEAU X 61 AVERDOINGT 63 AVESNES LE COMTE 64 AVESNES LES BAPAUME 1 ARRONDISSEMENT D'ARRAS ZONAGE ET DELIBERATIONS DANS LES COLLECTIVITES LOCALES AFR 2007/2013 PERMANENT AFR 2007/2008 TRANSITOIRE ZONAGE DELIBERATIONS AU NIVEAU DE L EPCI DELIBERATIONS AU NIVEAU COMMUNAL ZONES FRANCHES ZONES FRANCHES Innovantes Communes Communes éligibles éligibles en Communes partiellement Communes totalité aux aides éligibles Code Communes aux aides -

Télécharger Le Rapport

CommunautéCommunauté dede communescommunes FlandreFlandre LysLys RapportRapport d’activitéd’activité 2019 Organisation de la structure Créée en décembre 1992, la Communauté de communes Flandre Lys regroupe 8 communes pour un total de 40 239 habitants. 4 communes du Nord : Estaires, Haverskerque, La Gorgue, Merville 4 communes du Pas-de-Calais : Fleurbaix, Laventie, Lestrem, Sailly-sur-la-Lys Le Président À la suite des élections municipales de mars 2014, Bruno FICHEUX, Maire d’Estaires a été élu Président. Les vice-présidents Joseph CATTEAU, Maire de Fleurbaix : Finances Joël DUYCK, Maire de Merville : Emploi, développement économique et touristique Philippe MAHIEU, Maire de La Gorgue : Aménagement de l’espace Jean-Claude THOREZ, Maire de Sailly-sur-la-Lys : Mutualisation des compétences, transfert de compétences, juridique Geneviève FERMENTEL, Adjointe au maire de Laventie : Logement et Affaires sociales Anne HIEL, Conseillère municipale à Lestrem : Santé et Petite Enfance Michel DEHAENE, Adjoint au maire d’Estaires : Jeunesse, sport, culture et animation Pierre-Luc RAVET, Adjoint au maire de Sailly-sur-la-Lys : Mobilité, développement durable et digital Les membres du bureau Le bureau est composé du Président, des vice-présidents ainsi que de 7 autres membres titulaires : Pascale ALGOET, Adjointe au Maire d'Estaires Jean-Philippe BOONAERT, Maire de Laventie Bernard COTTIGNY, Adjoint au Maire de Fleurbaix Michel DUPAS, Adjoint au Maire de La Gorgue Philippe KUJAWA, Adjoint au Maire de Merville Jacques HURLUS, Maire de Lestrem Jean-Michel LAROYE, Maire d’Haverskerque (à compter de septembre 2016) L’équipe administrative 2019 Au 31 décembre 2019, l’effectif de la CCFL s’élève à 33 agents permanents et 6 non permanents. -

Civilité Nom De Naissance 2Ème Nom Prénom Ville

Civilité Nom de naissance 2ème nom Prénom Ville Madame ALLAIS Juliette Beaurains Madame BAILLET Alexe Merlimont Madame BARA Coline Liévin Madame BARBENSON Laurina Violaines Monsieur BARBIER Corentin Hames-Boucres Madame BAUDELET Emma Calonne-Ricouart Madame BAZET Maryam Hénin-Beaumont Madame BEAUCHENE Nathalie Vitry-en-Artois Madame BEGUE Amélie Bainghen Madame BELLOY Flora Samer Monsieur BENCTEUX Adrien Ruitz Madame BENS Lea Sangatte Monsieur BIGAND Benoît Hucqueliers Madame BLANCHARD Margot Beaurains Madame BONGE Charlotte Lillers Monsieur BOUKHATEB Nasrédine Courrières Madame BOUKHENFOUF Léa Coquelles Madame BOURDON Charlotte Saint-Venant Monsieur BOUTEILLE Pascal Oye-Plage Madame BOUZIN Mary Carvin Madame BURGI Romane Dainville Madame CALOIN Gabrielle Étaples Hesdigneul-lès- Madame CANESSE Marie Béthune Madame CARLIER Blanche Calais Madame CARPE Laura Wimereux Madame CARRE Amélie Harnes Madame CASTELLE Cindy Calais Monsieur CAUX Astrid-Edda Condette Madame CHAMBAULT Lohan Berck Madame CHARLEMAGNE Suzie Rinxent Madame CIESIELSKI Léa Labourse Madame CIURLIK Pauline Herbelles Madame CLIPET Typhaine Marconnelle Madame COLLÉ Sandrine Arras Madame CORBANESI Salomé Baincthun Madame COULOMBEL Alizée Samer Madame COULPIER Chloé Berck Madame COUSIN Emelie Samer Madame DACQUIN Constance Questrecques Madame DANHIEZ Léa Courrières Madame DARCHEVILLE Romane Nielles-lès-Ardres Madame DARIO DELPLANQUE Elodie Grenay Madame DE CONCEICAO Norma Béthune Madame DE DECKER Anaïs Wingles Monsieur DEBETTE Loic Auchy-lès-Hesdin Madame DEBILLIO RICHARD Geovanna -

SIP De Lens Par Fusion Des SIP De Lens Nord Et Lens Sud

Nouveau réseau de proximité du Pas-de-Calais Projet de calendrier des opérations Document de travail soumis à la réflexion 1 Présentation de la démarche La démarche a été initiée le 6 juin 2019 par le Ministre à Montreuil- sur-Mer devant les maires du Pas-de-Calais La concertation a été engagée aux côtés du Préfet depuis juin 2019 avec les personnels, les élus et les partenaires de la DGFiP. Elle a permis d’ajuster le projet initial de cartographie du nouveau réseau des finances publiques du Pas-de-Calais. A ce stade, les principales évolutions portent sur : - la création de SGC à Bapaume et Fruges, ainsi que 2 antennes SGC à Fauquembergues et St-Venant ; - le maintien d'une antenne à Saint-Pol du SIP d'Arras, d'une antenne à Saint-Omer du SIE de Calais et d'une antenne à Montreuil-sur-Mer, du SIE de Boulogne-sur-Mer ; - le maintien de la localisation de la BDV et de la BCR à Arras. La mise en place de cette nouvelle cartographie d’ici 2023 implique d’organiser et de planifier les transferts d’activité nécessaires. Le projet de calendrier communiqué permet d’atteindre cet objectif. 2 Les principes retenus pour établir le calendrier . Les contraintes actuelles des systèmes informatiques (SPL notamment) ne permettent de mener des opérations qu’aux 1er janvier ou 1er septembre de chaque année. Des points de contacts et des conseillers aux décideurs locaux (CDL) seront implantés dès que nos propres services quitteront une commune. La continuité des services offerts à nos usagers (élus et particuliers) sera ainsi assurée.