Augustus's Territorial Reform, Respectful Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pearl of Lake Como

A B C D E F G H I MAP 1 COMO LOC. RONCHI 1 1 VERGONESE LOC. CRELLA The Pearl of Lake Como LOC. CROTTO VILLA TROTTI S. GIOVANNI 2 P “The most exclusive 2 resort on Lake Como. GUGGIATE So beautiful, so breathtaking, VILLA TRIVULZIO GERLI so comfortable, so unique. MULINI DEL PERLO LOPPIA you’ll feel in heaven. 3 3 VILLA SUIRA MELZI LAGO DI COMO CIVENNA S. PRIMO That’s Bellagio!” MAGREGLIO P ERBA SCEGOLA LIDO TARONICO AUREGGIO CASATE 4 4 P BORGO VISGNOLA P REGATOLA BUS VILLA PARKING P SERBELLONI S. MARTINO VILLA GIULIA PESCALLO PUNTA SPARTIVENTO 5 OLIVERIO 5 S. VITO O ECC LAGO DI LECCO L A B C D E F G H I MAP OF THE CENTRE OF BELLAGIO Boat Terminal Letter Box Imbarcadero Buca delle lettere Car Ferry Terminal Autotraghetto Tourist Office / Ufficio Informazioni Tel. e Fax +39.031.950.204 Bus Terminal Fermata autobus PromoBellagio Office Public toilets Ufficio PromoBellagio Bagni pubblici Tel. e Fax +39.031.951.555 Pharmacy [email protected] Farmacia www.bellagiolakecomo.com T U V W X Y Z GIARDINI DI VILLA MELZI L I D O DI V I A BELLAGIO P . C A R C A N O 1 LAGO 1 LUNGOLA DI COMO R I O EU RO P A P L U N G O L A R IO M A R C O N I CAR FER RY TERMINAL TOURIST OFFICE / UFFICIO INFORMAZIONI BOAT TERMINAL / IMBARCADERO 2 P 2 I MAZZIN PIAZZA A M P O O I O A R I F R E A I F T N D A R A A O I S R N I R U L L V U E NG MANZONI A OLARIO A N A L O C I N R E V M L G O A M P PHARMACY A M C A T PARCO T FARMACIA I I L I C O MUNALE L E I A I A C E N T R A L A V N S N S I O I A A A D A T T T T N ELL A B R BIBLIOTECA ALI ALI ALI ALI G S S S S VIA ER A VIA E. -

XXX Coordinamento Brianza Sicura | Barlassina – Lunedì 28 Gennaio 2019

Report riunione di Coordinamento Brianza SiCura XXX Coordinamento Brianza SiCura | Barlassina – lunedì 28 gennaio 2019 In data 28 gennaio 2019 alle h 21 presso la Sala Consiliare del Comune di Barlassina (MB) si è svolta la trentesima riunione intercomunale di Brianza SiCura. Presenti alla riunione 27 persone, tra cui - i Sindaci di Barlassina, Cesano Maderno, Seveso - i delegati Bsc di Nova Milanese, Lissone, Cesano Maderno, Arcore - consiglieri comunali di Barlassina, Seveso, Bovisio Masciago. Desio, Lentate, Limbiate, Varedo, Cesano Maderno - cittadini di Desio, Barlassina, Lissone, Muggiò, Varedo, Cesano Maderno, Seveso. Assume la presidenza il vice-coordinatore Roberto Beretta 3. Varie ed eventuali Dopo l'introduzione e i saluti del Sindaco di Barlassina, Beretta chiede di invertire l’ordine del giorno per comunicare brevemente due “buone notizie”: - l'invito a partecipare a un incontro della Commissione consiliare Legalità del Comune di Seregno per spiegare le attività di Bsc in vista di una possibile prossima adesione del Comune stesso; - la richiesta, da parte della cooperativa sociale Atipica, di collaborare con una lezione a un corso di formazione per la legalità e la trasparenza dedicato ad insegnanti del Vimercatese. In progetto per il prossimo anno scolastico, con la stessa coop sociale, un corso di educazione alla legalità destinato agli alunni delle scuole superiori. 1. Discussione della bozza di Statuto di Brianza SiCura Beretta ricapitola le ragioni tecniche (nuova legge del Terzo settore, possibilità di agire economicamente) e legali (necessità di avere una personalità giuridica e di chiarire le responsabilità legali nell’associazione) per cui da qualche mese si è intrapresa la definizione di un nuovo statuto, la cui bozza – elaborata da uno Studio specializzato – è stata distribuita in precedenza ai delegati e agli aderenti di Bsc. -

Libretto Orari Linea Z315 in Vigore Dal 01-04-19

I I I LIBRETTO ORARI I LINEA Z315 IN VIGORE DAL 01-04-19 Per informazioni: NET NordEst Trasporti Num.Verde 800-90.51.50 ore 7.30-19.30 tutti i giorni Z315 Z315-As GORGONZOLA M2 - VIMERCATE .............................................. 4 Z315-Di VIMERCATE - GORGONZOLA M2 ................................................. Indice Fermate Via Giotto VIMERCATE AGRATE BRIANZA Autostazione Vimercate Dante Alighieri Burago De Gasperi Centro Omnicomprensivo Filzi Cremagnani Filzi Fermi Lecco Matteotti Stabilimento ST Milano Via Matteotti Monza ARCORE Ronchi (Ospedale) Battisti Via Galbussera Battisti Via Galbussera De Gasperi Monginevro Via San Carlo BURAGO DI MOLGORA 25 Aprile 25 Aprile Martiri della Liberta' Martiri della Liberta' CAPONAGO Via S. Pellico Via Senatore L. Simonetta Via V. Emanuele GORGONZOLA Stz Gorgonzola M2 PESSANO CON BORNAGO 1 Maggio Alighieri Castello Europa Manzoni Manzoni Monte Grappa Piave Porta Provinciale R. da Pessano Roma Strada Provinciale 120 Tobagi Z315-As GORGONZOLA M2 - VIMERCATE lunedì-venerdì Note z2 z2 z2 GORGONZOLA M2 06.15 06.35 06.45 07.00 07.10 07.15 07.40 08.15 08.50 09.25 10.00 11.05 12.10 PESSANO B. via_Pasubio 06.19 06.39 06.48 07.05 07.15 07.20 07.44 08.19 08.54 09.29 10.04 11.09 12.14 PESSANO B. Castello 06.24 06.44 07.12 07.22 07.27 07.49 08.24 09.34 10.09 12.19 PESSANO B. Tobagi 06.54 09.00 11.15 CAPONAGO Pellico 06.26 06.46 06.57 07.15 07.25 07.30 07.53 08.28 09.05 09.38 10.13 11.20 12.23 CAPONAGO Emanuele 06.30 06.50 07.00 07.20 07.30 07.35 07.59 08.34 09.10 09.44 10.19 11.25 12.29 AGRATE B. -

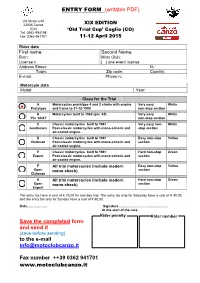

ENTRY FORM (Writable PDF) Save the Completed

ENTRY FORM (writable PDF) Via Meda n.40 22035 Canzo XIX EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-941701 11-12 April 2015 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles prototype 4 and 2 stroke with engine Very easy White Prototype and frame to 31-12-1990 non-stop section B Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T non-stop section C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Ver y easy non - White Gentlemen Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and stop section air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Easy non -stop Yellow Clubman Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. E Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Hard non -stop Green Expert Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. F All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non -stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman G All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non -stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 75,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 40,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 40,00. Data……………… Signature……………………………………… At the start of the race Rider penalty Rider number Save the completed form and send it (save before sending) to the e-mail [email protected] Fax number ++39 0362 941701 www.motoclubcanzo.it How reach the trial in Caglio (CO) From Turin : Highway Turin-Milan following on the west ring of Milan to direction Venice and exit to Cinisello Balsamo toward the highway Milan-Lecco direction Lecco. -

The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy

The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy RICERCA N°07/2016 Edited by Gruppo Chimici and Centro Studi The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy This Research has been carried out by: Centro Studi and Gruppo Chimici, Assolombarda Confindustria Milano Monza e Brianza Centro Studi, Farmindustria Centro Studi, Federchimica We thank Unioncamere Lombardia for industrial production data Contents 1. FOREWORD 5 2. THE CHEMICAL AND PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY IN LOMBARDY 6 Key figures 6 The size of the industry 9 Industrial production trends between 2007 and the second quarter of 2016 11 The international perspective 12 R&D activities 14 1. Foreword I am very pleased to disclose to you “The Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry in Lombardy”. This research is promoted by Gruppo Chimici Assolombarda, a group of firms associated to Assolombarda Confindustria Milano Monza e Brianza currently including about 680 companies and almost 50,000 employees, which I have the honour to represent. The aim is to provide an all-round analysis and work tool, acting as a basis for an industrial policy proposal that recognises the significance of those sectors, both at local and national level. Lombardy is particularly cut out for the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry, thanks to an efficient network of companies and industrial clients, universities and research centres, plant design companies and advanced services. The Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry means innovation. It stays ahead of the market and lays the basis for future Italian growth. The crisis has not left us unscathed, but the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industry is recovering from the crisis, with Lombardy giving a head start. -

Elezioni U.P.S. 2020 Elenco Alfabetico Pescatori Residenti Fuori Provincia Di Sondrio - Votanti/Eleggibili

ELEZIONI U.P.S. 2020 ELENCO ALFABETICO PESCATORI RESIDENTI FUORI PROVINCIA DI SONDRIO - VOTANTI/ELEGGIBILI Abbondi Italo Alberto Cabiate Aberle Ernst Crandola Valsassina Aberle Rudi Margno ACCONCIAGIOCO GIUSEPPE Rodano Aceto Alessio Brugherio Acquati Sergio Lentate sul Seveso Acquistapace Aldo Pessano Con Bornago Aili Lino Cadenazzo Aiolfi Antonio Bagnolo Cremasco Albini Fernando Bergamo Alietti Pierluigi Domaso Aliprandi Carlo Monza AMATI JACOPO PABLO Milano ANDREANA ANTONIO Seregno Angeleri Gabriele Milano Angeli Emilio Meda Angeli Luigi Meda Angioletti Giovanni Mandello Del Lario Anni Marco Verolavecchia Annoni Angelo Meda Antimiani Paolo Milano Antonielli Eugenio Cervignano D'adda Antonioli Roberto Abbiategrasso APPELLA ETTORE ANDREA Saronno Appennini Stefano Verano Brianza appiani luca Vimercate Ardigo' Antonio Dorio Arena Domenico Seregno Aresi Franco Cardano Al Campo Argenti Federico Milano Argenti Villiam Milano Arnaboldi Sergio Calco Arnoldi Danilo Sueglio Arnoldi Marco Dervio Arrigo Marco Montorfano ARRIGONI MATTEO Mandello Del Lario Arrigotti Carlo Attilio Antonio Milano ARZENI FABRIZIO Cadrezzate Ascorti Pietro Bregnano Asnaghi Danilo Giussano Auguadro Cesare Orsenigo auteri francesco Milano Avella Daniele Milano Azzoni Mauro Busto Arsizio Baccolo Giovanni Milano Baccolo Paolo Milano BAGGIO ALESSANDRO Masate Bailo Marco Monza Balconi Isidoro Renate Balducci Adriano Giussano Balice Claudio Lissone Ballabio Daniele Giussano Ballabio Dino Lentate Sul Seveso Ballabio Eugenio Giussano Ballabio Mauro Senna Comasco Ballabio Paolo -

Parere Vincolante Sulla Proposta Del Consiglio Di Amministrazione in Merito Alla Dichiarazione Di Non Salvaguardia Dell

Conferenza dei Comuni Parere reso ai sensi dell’art.49 N° 2 della Brianza L.R. 26/03 e s.m.i del 19.10.2016 Oggetto: Parere vincolante sulla proposta del Consiglio di Amministrazione in merito alla dichiarazione di non salvaguardia della gestione, da parte della Società 2I rete Gas S.p.A. del servizio di distribuzione dell’acqua potabile nel territorio del Comune di Villasanta Alle ore 17.30 del giorno 19 Ottobre 2016 presso la sede della Provincia di Monza e della Brianza, in Via Grigna n. 13 – Monza, si è riunita la Conferenza dei Comuni per l’Ambito Territoriale Ottimale del Servizio Idrico Integrato e all’appello sono risultati presenti i Sindaci, o loro delegati, dei Comuni di: Comune Sì/no Comune Sì/no Comune Sì/no Agrate Brianza Ceriano Laghetto Nova Milanese Aicurzio Cesano Maderno Ornago Albiate Cogliate Renate Arcore Concorezzo Roncello Barlassina Cornate D'Adda Ronco Briantino Bellusco Correzzana Seregno Bernareggio Desio Seveso Besana in Brianza Giussano Sovico Biassono Lazzate Sulbiate Bovisio Masciago Lentate sul Seveso Triuggio Briosco Lesmo Usmate Velate Brugherio Limbiate Varedo Burago Molgora Lissone Vedano al Lambro Busnago Macherio Veduggio con Colzano Camparada Meda Verano Brianza Caponago Mezzago Villasanta Carate Brianza Misinto Vimercate Carnate Monza Cavenago Brianza Muggiò TOTALE xx/55 La Presidenza della Conferenza viene assunta dal Sindaco di Monza Roberto Scanagatti. Assiste alla seduta il Presidente del Consiglio d’Amministrazione dell’ATO-MB Silverio Clerici. Assiste altresì il direttore di ATO-MB Egidio Ghezzi che redige il presente verbale, costituito da n. 6 pagine. Il Presidente della Conferenza, riscontrato la presenza del numero legale di componenti, dichiara aperta la riunione per la trattazione dell’argomento posto all’ordine del giorno, su richiesta del Presidente del C.d.A. -

Abano Terme Acerra Aci Castello Acqualagna Acquanegra

Abano Terme Alzano Scrivia Azzano San Paolo Belvedere Marittimo Acerra Amelia Azzate Benevento Aci Castello Anagni Bagnaria Benna Acqualagna Ancarano Bagnatica Bentivoglio Acquanegra Cremonese Ancona Bagno A Ripoli Berchidda Adro Andezeno Bagnoli Di Sopra Beregazzo Con Figliaro Affi Angiari Bagnolo Cremasco Bereguardo Afragola Anguillara Veneta Bagnolo Di Po Bergamo Agliana Annicco Bairo Bernareggio Agliano Annone Di Brianza Baone Bertinoro Agliè Antrodoco Baranzate Besana in Brianza Agna Anzola D’Ossola Barasso Besenello Agordo Aosta Barbarano Vicentino Besnate Agrate Brianza Appiano Gentile Barberino Di Mugello Besozzo Agugliano Appiano sulla strada del vino Barberino Val D’Elsa Biassono Agugliaro Aprilia Barbiano Biella Aicurzio Arce Barchi Bientina Ala Arcene Bardello Bigarello Alano Di Piave Arco Bareggio Binago Alba Arconate Bariano Bioglio Alba Adriatica Arcore Barlassina Boara Pisani Albairate Arcugnano Barone Canavese Bolgare Albano Laziale Ardara Barzago Bollate Albaredo Arnaboldi Ardea Barzanò Bollengo Albaredo D’Adige Arese Basaluzzo Bologna Albavilla Arezzo Baselga Di Pinè Bolsena Albese Con Cassano Argelato Basiano Boltiere Albettone Ariccia Basiliano Bolzano Albiano Arluno Bassano Bresciano Bolzano Vicentino Albiate Arquà Petrarca Bassano Del Grappa Bomporto Albignasego Arquà Polesine Bassano In Teverina Bonate Sotto Albino Arre Bastida Pancarana Bonemerse Albiolo Arsago Seprio Bastiglia Bonorva Albisola Superiore Artegna Battaglia Terme Borghetto S. Spirito Albuzzano Arzachena Battuda Borgo San Dalmazzo Aldeno Arzano Baveno -

Elenco Sedi E Orari Sportelli Di Prossimita'

ELENCO SEDI E ORARI SPORTELLI DI PROSSIMITA’ SPORTELLO DI MONZA SPORTELLO DI SEREGNO Serve i cittadini provenienti da: Serve i cittadini provenienti da: Monza, Villasanta, Brugherio. Seregno, Barlassina, Cogliate, Giussano, Lazzate, Lentate sul Seveso, Meda, Misinto, Seveso. Via E. Da Monza n. 4 presso il Servizio Territoriale Comunale Via Oliveti n° 17 - Seregno disabili adulti presso i Servizi Sociali del Comune Giorni e orari di apertura: Giorni e orari di apertura: lunedì dalle 14.00 alle 17.00 martedì dalle ore 09.00 alle ore 12.30 giovedì dalle 14.30 alle 17.00 giovedì dalle ore 16.00 alle ore 18.00 Riceve su appuntamento telefonando al n. Telefono: 0362 263401 039 – 3946138 [email protected] [email protected] Per le casistiche più complesse e strutturate è Per le casistiche più complesse e strutturate inoltre disponibile un servizio di consulenza è inoltre disponibile un servizio di consulenza esperta a cura di avvocati volontari. esperta a cura di avvocati volontari. Rivolgersi allo Sportello per fruire di questo Rivolgersi allo Sportello per fruire di questo servizio. servizio. SPORTELLO DI DESIO SPORTELLO DI LISSONE Serve i cittadini provenienti da: Serve i cittadini provenienti da: Desio, Muggiò, Nova Milanese, Varedo, Carate Brianza, Lissone, Vedano al Lambro, Bovisio Masciago, Cesano Maderno, Biassono, Macherio, Sovico, Albiate, Triuggio, Ceriano Laghetto,Solaro. Besana Brianza, Verano Brianza, Briosco, Renate, Veduggio con Colzano. Via Gramsci, 3 - Desio presso il Palazzo Comunale - piano terra Via Gramsci, 21 - -

Provincia Di Monza E Della Brianza Comune Di Busnago (MB) Avviso Ai Creditori Lavori Di Scarifica Ed Asfaltatura Pavimentazioni Stradali - Avviso Ai Creditori

– 352 – Bollettino Ufficiale Serie Avvisi e Concorsi n. 33 - Mercoledì 14 agosto 2019 Provincia di Monza e della Brianza Comune di Busnago (MB) Avviso ai creditori lavori di scarifica ed asfaltatura pavimentazioni stradali - Avviso ai creditori IL RESPONSABILE UNICO DEL PROCEDIMENTO Visto l’art. 216, comma 16, del d.lgs. 50/2016 e s.m.i.; In esecuzione del disposto dell’art. 218 del d.p.r. 5 ottobre 2010, n. 207 RENDE NOTO che in data 21 giugno 2019 sono ultimati i lavori di «Scarifica ed asfaltatura pavimentazioni stradali» di cui alla Scrittura Pubblica Amministrativa Rep. n. 174 del 24 aprile 2019, registrata presso l’A- genzia delle Entrate di Vimercate il 3 maggio 2019 l n. 11, serie I. INVITA tutti coloro che per indebite occupazioni di aree o di stabili e per danni arrecati nell’esecuzione dei lavori fossero ancora creditori verso l’impresa MALACRIDA A.V.C. s.r.l. – Via XXV Aprile, 18 – Lesmo (MB) – C.F. e P.IVA 073771130963, appaltatrice dei lavori di «Scarifica ed asfaltatura pavimentazioni stradali» – CUP B57H18004220004 – CIG 773809914E, a presentare presso l’Ufficio Protocollo del Comune di Busnago (MB) – Piazzetta Marconi n. 3, le domande ed i titoli a loro credito entro trenta giorni decorrenti dalla data di pubblicazione del presente avviso sul BURL e all’Al- bo Pretorio Comunale. Trascorso tale periodo non sarà più tenuto conto in via ammi- nistrativa dei titoli prodotti. Busnago, 1 agosto 2019 Il responsabile unico del procedimento Raffaele Manzo Comune di Lentate sul Seveso (MB) Piano attuativo di iniziativa privata in variante al vigente piano di governo del territorio (PGT) per la demolizione e ricostruzione di immobile ad uso commerciale – Ambito territoriale «Area ex Carrefour» via Nazionale – Proprietà Reale Immobili s.r.l. -

Disponibilità Primaria

PROSPETTO ORGANICO, TITOLARI E DISPONIBILITA' SCUOLA PRIMARIA ANNO SCOLASTICO DI RIFERIMENTO : 2021/22 - SITUAZIONE A PRIMA DEI MOVIMENTI UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE: LOMBARDIA UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE: MONZA E DELLA BRIANZA Codice Scuola Denominazione Scuola Codice Tipo Posto Denominazione Tipo Posto Tipo Scuola Comune Disponibilità MBCT701001 C.T.P. C/O S.M.S. "RODARI" DESIO ZJ CORSI DI ISTR. PER ADULTI SERALE DESIO 0 MBCT70400C C.T.P. C/O I.C. VIA EDISON ZJ CORSI DI ISTR. PER ADULTI SERALE ARCORE 0 MBCT705008 C.T.P. C/O S.M.S. "CONFALONIERI" MONZA ZJ CORSI DI ISTR. PER ADULTI SERALE MONZA 2 MBCT70700X C.T.P. C/O S.M.S."L.DA VINCI" LIMBIATE ZJ CORSI DI ISTR. PER ADULTI SERALE LIMBIATE 0 MBEE70502N CASA CIRCONDARIALE - MONZA QN CARCERARIA CARCERARIA MONZA 1 MBEE81201L RIMEMBRANZE - VEDANO AL LAMBRO AN COMUNE NORMALE VEDANO AL LAMBRO 2 MBEE81201L RIMEMBRANZE - VEDANO AL LAMBRO EH SOSTEGNO PSICOFISICO NORMALE VEDANO AL LAMBRO 3 MBEE81201L RIMEMBRANZE - VEDANO AL LAMBRO IL LINGUA INGLESE NORMALE VEDANO AL LAMBRO 0 MBEE82602G "S.ANDREA"- BIASSONO AN COMUNE NORMALE BIASSONO 1 MBEE82602G "S.ANDREA"- BIASSONO EH SOSTEGNO PSICOFISICO NORMALE BIASSONO 2 MBEE829012 G.UNGARETTI - ALBIATE AN COMUNE NORMALE ALBIATE 3 MBEE829012 G.UNGARETTI - ALBIATE EH SOSTEGNO PSICOFISICO NORMALE ALBIATE 8 MBEE830016 G.D.ROMAGNOSI - CARATE BRIANZA AN COMUNE NORMALE CARATE BRIANZA 4 MBEE830016 G.D.ROMAGNOSI - CARATE BRIANZA EH SOSTEGNO PSICOFISICO NORMALE CARATE BRIANZA 6 MBEE831045 ALFREDO SASSI - RENATE AN COMUNE NORMALE RENATE 5 MBEE831045 ALFREDO SASSI -

R.U. 66463 IL DIRETTORE Vista La Determinazione Prot. N. 2001/UD Del 30 Novembre 2007, Pubblicata Sulla G.U. Del 10 Dicembre

R.U. 66463 IL DIRETTORE Vista la determinazione prot. n. 2001/UD del 30 novembre 2007, pubblicata sulla G.U. del 10 dicembre 2007, n. 286 – serie generale -, con cui è stato istituito ed attivato, in via sperimentale, tra l’altro anche l’Ufficio delle dogane di Milano 2 con competenza sulla relativa provincia, ad esclusione del Comune di Milano, e sulla provincia di Lodi; Vista la nota n. 200/AA.GG./2009 del 16 febbraio 2009 con cui il Commissario Governativo della Provincia di Monza e Brianza ha comunicato che tale nuova provincia, istituita con la legge 11 giugno 2004, n. 146, con le prossime consultazioni elettorali del 6 e 7 giugno 2009 entrerà nel pieno della propria attività; Ritenuta la necessità di meglio specificare la competenza territoriale del citato Ufficio delle dogane di Milano 2, per renderlo più aderente alla nuova realtà dei locali enti autarchici territoriali; ADOTTA LA SEGUENTE DETERMINAZIONE Art. 1 Specificazione della competenza territoriale dell’Ufficio delle dogane di Milano 2. A parziale modifica dell’art. 1, comma 6, della determinazione direttoriale n. 2001/UD del 30 novembre 2007, l’Ufficio delle dogane di Milano 2 ha competenza territoriale sulla provincia di Milano, con esclusione del Comune di Milano, sulla provincia di Lodi e sulla nuova provincia di Monza e Brianza, comprendente i Comuni di: Agrate Brianza, Aicurzio, Albiate, Arcore, Barlassina, Bellusco, Bernareggio, Besana in Brianza, Biassono, Bovisio Masciago, Briosco, Brugherio, Burago di Molgora, Camparada, Carate Brianza, Carnate, Cavenago di Brianza, Ceriano Laghetto, Cesano Maderno, Cogliate, Concorezzo, Correzzana, Desio, Giussano, Lazzate, Lesmo, Limbiate, Lissone, Macherio, Meda, Mezzago, Misinto, Monza, Muggiò, Nova Milanese, Ornago, Renate, Ronco Briantino, Seregno, Seveso, Sovico, Sulbiate, Triuggio, Usmate Velate, Varedo, Vedano al Lambro, Veduggio con Colzano, Verano Bria nza, Villasanta, Vimercate.