Irigaray and Politics a Critical Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversation with Rosi Braidotti 27/01/16 11:33

Conversation with Rosi Braidotti 27/01/16 11:33 nYwebsite en tijdschrift voor literatuur, kritiek & amusement, voorheen yang & freespace Nieuwzuid Nieuwste nummer > Transitzone/ RosiConversation Braidotti, Sarah Posman with Rosi Braidotti Published: 19/06/2013 Tags: litcrit interview philosophy psychoanalysis Sarah Posman (nY) in conversation with Rosi Braidotti on contemporary feminism and amor fati, in March 2012. Sarah Posman: In Metamorphosis: Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming you write that “time is on our side.” Do you still feel that way in the light of the present moments of crisis that we’re witnessing in society and academia – the lack of funding for Women’s Studies departments in the low countries is an urgent example. When there is revolt against these developments – the riots in cities across Europe, the academe-affiliated Occupy movements – it doesn’t seem to come in the Dionysian guise you promote. Rosi Braidotti: The phrase “time is on our side” is grounded both in an intellectual and institutional practice of feminism. For me feminist theory is transformative. This implies a debate with gender and gender mainstreaming, which is one of the great growth areas not only of the academe but of our society, and an area that will produce a great deal of employment for our students. Gender mainstreaming is egalitarian and terribly important. I support it completely, but it is not transformative, necessarily. I was watching TV last night, on the eve of international women’s day, and all the major international networks were doing features on the status of women. Al Jazeera had a wonderful set of interviews about women in the Arab world and women entrepreneurs in India. -

The Other Woman. Towards a Diffractive Rereading of the Oeuvres of Simone De Beauvoir and Luce Irigaray

Faculty of Humanities Research Institute for History and Culture (OGC) RMA Gender and Ethnicity, 2011-2012 The Other Woman. Towards a diffractive rereading of the oeuvres of Simone de Beauvoir and Luce Irigaray. Research master thesis, Gender and Ethnicity Written by Evelien Geerts, 3615170 Supervisor: dr. Iris van der Tuin (Utrecht University) Second reader: dr. Annemie Halsema (VU-University) Utrecht, 20/07/2012. Abstract. This thesis project –a project that has to be located in the domains of Continental philosophy, feminist theory, and gender studies– wishes to overcome the Oedipalized reception history, or the Oedipal feminist narratives that have been created and told about the oeuvres of feminist philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and Luce Irigaray. I claim that this Oedipalized reception history –which will be thoroughly reviewed in this thesis– put the works of Beauvoir and Irigaray against one another in an oppositional and hierarchic manner, by first of all examining the wide-spread assumption that Irigaray should be seen as Beauvoir’s rebellious daughter, and by critically looking at the idea that Irigaray’s sexual (now relabeled as sexuate) difference philosophy then must be a flat-out refusal of Beauvoir’s humanist, existentialist feminism. My project hopes to shed light on this paralyzing constructed opposition, and wishes to move towards a different kind of feminist rereading and story-telling: namely, a diffractive and explicitly an-Oedipal way of telling of stories that would look for the lines of continuity between these two philosophies, without reducing them to another; without, to put it differently, falling back into the phallogocentric, reflective logic of sameness. -

Reclaiming Luce Irigaray: Language and Space of the "Other"

Linguistics and Literature Studies 6(5): 250-258, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2018.060508 Reclaiming Luce Irigaray: Language and Space of the "Other" Zhang Pinggong The Faculty of English Language and Culture, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract French feminist Luce Irigaray takes up some and women’s meaning-making in language. She argues essential conceptions of post-structuralist thinkers as a that this difference is shaped by the female body and rests start-point, and advances arguments on the logical in women’s capacity for decentred, multiple sexuality and oppositions based on male and female dichotomy. women’s language. She contends that women’s identity According to Irigaray, this dichotomy is explicitly related can be autonomous and explorable only within a radically to language. In order to subvert discursive hegemony of separatist women’s movement. Some essential concepts of patriarchy, it is imperative for women to invent and utilize feminist theory advanced by Lucy Irigaray will shed light a language strikingly different from that of the male. This on the understanding and criticism of own feminist theory innovative language, also known as “parler femme” or and, more generally, of the French school of thought on space of the “other”, can be employed to construct gender politics. Focusing on Irigaray’s tenets about women’s subjectivity. Irigaray prioritizes language over sexuality and language, the author of this essay attempts to social conscious and ideologies, considering physical and discuss the essential themes of this “French side of the spiritual difference between women and men as divide”, indicating that although the theories of the French instrumental for women’s sovereignty and identity. -

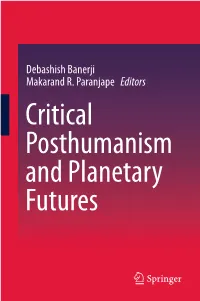

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures 123 Editors Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape California Institute of Integral Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University San Francisco, CA New Delhi USA India ISBN 978-81-322-3635-1 ISBN 978-81-322-3637-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947189 © Springer India 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer (India) Pvt. -

1 Essentialism and Anti-Essentialism in Feminist Philosophy Alison Stone

1 Essentialism and Anti-Essentialism in Feminist Philosophy Alison Stone The heated feminist debates over ‘essentialism’ of the 1980s and early 1990s have largely died away, yet they raised fundamental questions for feminist moral and political philosophy which have still to be fully explored. Centrally at issue in feminist controversies over essentialism was whether there are any shared characteristics common to all women, which unify them as a group. Many leading feminist thinkers of the 1970s and 1980s rejected essentialism, particularly on the grounds that universal claims about women are invariably false and effectively normalise and privilege specific forms of femininity. However, by the 1990s it had become apparent that the rejection of essentialism problematically undercut feminist politics, by denying that women have any shared characteristics which could motivate them to ask together as a collectivity. An ‘anti-anti-essentialist’ current therefore crystallised which sought to resuscitate some form of essentialism as a political necessity for feminism. i One particularly influential strand within this current has been ‘strategic’ essentialism, which defends essentialist claims just because they are politically useful. In this paper, I aim to challenge strategic essentialism, arguing that feminist philosophy cannot avoid enquiring into whether essentialism is true as a descriptive claim about social reality. I will argue that, in fact, essentialism is descriptively false, but that this need not undermine the possibility of feminist activism. This is because we can derive an alternative basis for feminist politics from the concept of ‘genealogy’ which features importantly within some recent theoretical understandings of gender, most notably Judith Butler’s ‘performative’ theory of gender. -

A Research Agenda for an Ecofeminist-Informed Ecological Economics

sustainability Article Transcending the Learned Ignorance of Predatory Ontologies: A Research Agenda for an Ecofeminist-Informed Ecological Economics Sarah-Louise Ruder † and Sophia Rose Sanniti *,† School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † All authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 6 January 2019; Accepted: 6 March 2019; Published: 11 March 2019 Abstract: As a necessarily political act, the theorizing, debating and enacting of ecological economies offer pathways to radical socio-economic transformations that emphasize the ecological and prioritize justice. In response to a research agenda call for ecological economics, we propose and employ an ecofeminist frame to demonstrate how the logics of extractivist capitalism, which justify gender biased and anti-ecological power structures inherent in the growth paradigm, also directly inform the theoretical basis of ecological economics and its subsequent post-growth proposals. We offer pathways to reconcile these epistemological limitations through a synthesis of ecofeminist ethics and distributive justice imperatives, proposing leading questions to further the field. Keywords: ecological economics; ecofeminism; gender; capitalist-patriarchy; intersectionality; post-growth; transformational change; systems thinking; complexity As white-settlers in the Region of Waterloo, we acknowledge that we live and work on the traditional territory of the Attawandaron (Neutral), Anishnawbe, and Haudenosaunee peoples. The University of Waterloo is also situated on the Haldimand Tract: land promised to the Six Nations that includes ten kilometres on each side of the Grand River. We make this statement to act against the erasure of ongoing colonial legacies across Turtle Island and to acknowledge that we contribute to and benefit from the expulsion, assimilation, and genocide of Indigenous Peoples. -

Writing As a Nomadic Subject

Comparative Critical Studies 11.2–3 (2014): 163–184 Edinburgh University Press DOI: 10.3366/ccs.2014.0122 C British Comparative Literature Association www.euppublishing.com/ccs Writing as a Nomadic Subject ROSI BRAIDOTTI I am rooted but I flow Virginia Woolf, The Waves1 My lifelong engagement in the project of nomadic subjectivity has been partly motivated by the conviction that, in these globalized times of accelerating technologically mediated changes, many traditional points of reference and age-old habits of thought are being re-composed, albeit in contradictory ways. Paradoxically, old power relations are not only confirmed but in many ways exacerbated in the new geo-political context.2 At such a time more conceptual creativity is necessary, and more theoretical courage is needed in order to bring about the leap across inertia, nostalgia, aporia and the other forms of critical stasis induced by our historical condition. It has become like a mantra to me: we need to learn to think differently about the kind of subjects we have already become and the processes of deep-seated transformation we are undergoing. The philosopher in me believes that a new alliance between philosophy, the arts and science is a crucial building block for this qualitative shift of perspective.3 The writer in me, on the other hand, continues to muse about the complex ways in which the imaginary both propels and resists in-depth transformations. A MATTER OF STYLE At the beginning of it all, for my generation, is the commitment to writing. Presented as a form of political and ethical engagement, it is essentially a visceral gesture. -

Histories of the Present and Future Feminism, Power, Bodies Elizabeth Grosz

1 Histories of the Present and Future Feminism, Power, Bodies Elizabeth Grosz There is much about feminist theory that is in a state of flux right now; major transformations are occurring regarding how feminist politics and its long- and short-term goals and methods are conceived. The debates about the place of identity in political struggle, attempts to make feminism more inclusive, the ways in which even the body is conceptualized, the impact of feminism on young women and men, have, instead of producing a new more focused and cohesive feminist movement, simply witnessed the growing fragmentation and division within its ranks. I would like to look at some of the effects that some key theoretical/political changes have on the ways in which feminist scholarship and theory have changed or should change. In particular, I want to look at two paradigm shifts—shifts that have affected the ways we understand knowledge and power—which have occurred over the last decade or so and have transformed, or hopefully will transform, the way feminist scholarship and politics is undertaken and what its basic goals are. The first consists in transformations in our understanding of knowledges, discourses, texts, and histories, which politicizes them not only in terms of their contents—that is, in terms of what they say—but also in terms of the positions from which they are articulated (their modes of address)—what they cannot say—and what their positions are within a network of other texts that constitute both their milieu and the means by which they become both comprehensible and tamed. -

Rosi Braidotti, the Posthuman

The Posthuman The Posthuman Rosi Braidotti polity Copyright © Rosi Braidotti 2013 The right of Rosi Braidotti to be identifi ed as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 2013 by Polity Press Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4157-7 ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4158-4 (pb) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Group Limited, Bodmin, Cornwall The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. -

A Cartography of Angry Indian Goddesses Towards Nomadic Affect

Indi@logs Vol 7 2020, pp 11-25, ISSN: 2339-8523 DOI https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.150 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ A CARTOGRAPHY OF ANGRY INDIAN GODDESSES TOWARDS NOMADIC AFFECT INDRANI MUKHERJEE Jawaharlal Nehru University [email protected] Received: 31-10-2019 Accepted: 17-12-2019 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to draw a cartography of becoming Angry Indian Goddesses as transnational nomadism towards an embodied and material rethinking of women’s friendships from outside the constraints of systemic binaries. The friends are all professional women who are globally wired, whose thinking minds and non-docile bodies detach themselves from any normative modes of belonging in their respective personal and professional realms. They map a post-humanist spatiality of rhizomic linkages with other animate and non-animate entities, throwing up a new ethics of nomadic affect and responsibility. The film begins with a panoramic gaze of the Goan landscape, overlapped with flash images of Hindu goddesses and their animal escorts framed within a power packed song “Kattey”, which intersects Bhanwari Devi’s powerful folk composition of Meera Bai’s 15th century mystic tradition with Haard Kaur’s rap. The crossing of the song and the violent events of rejection that the women face, unbridle a becoming angry goddesses through a pastiche of the anxious goddesses and women sited on an axis of re/de-valorised difference. Goa becomes a potential third space entangled with all of the above, as it dwells on the contemplative scope of this cartography as redemptive and suggests a re-humanization of schizophrenic splintered objects through love and affect. -

Virginia Woolf, the Problem of Language, and Feminist Aesthetics

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 A Voice of One's Own: Virginia Woolf, the Problem of Language, and Feminist Aesthetics Lisa Karin Levine College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Levine, Lisa Karin, "A Voice of One's Own: Virginia Woolf, the Problem of Language, and Feminist Aesthetics" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625831. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-fz2e-0q20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Voice of One's Own: Virginia Woolf, the Problem of Language, and Feminist Aesthetics A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Lisa Karin Levine 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Lisa Karin Levine Approved, May 1993 Esther Lanigan, Chair Elsa Nettels Deborah Morse DEDICATION The author wishes to dedicate this text to Drs. Arlene and Joel Levine, without whose love and support none of this would be possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express her appreciation to Professor Esther Lanigan for her many hours of reading and invaluable criticism of this text, and also to Professors Deborah Morse and Elsa Nettels for their time and instruction. -

Derridean Deconstruction and Feminism

DERRIDEAN DECONSTRUCTION AND FEMINISM: Exploring Aporias in Feminist Theory and Practice Pam Papadelos Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry Adelaide University December 2006 Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................III DECLARATION .....................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................V INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 THESIS STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW......................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS – FEMINISM AND DECONSTRUCTION ............................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 FEMINIST CRITIQUES OF PHILOSOPHY..................................................................... 10 Is Philosophy Inherently Masculine? ................................................................ 11 The Discipline of Philosophy Does Not Acknowledge Feminist Theories......... 13 The Concept of a Feminist Philosopher is Contradictory Given the Basic Premises of Philosophy.....................................................................................