View the Redbank Creek Watershed Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 2 Markings Colonial -1865, Which, While Not Comprehen- Sive, Has the Advantage of Including Postal Markings As by Len Mcmaster Well As Early Postmasters6

38 Whole Number 242 Hampshire County West Virginia Post Offices Part 2 Markings Colonial -1865, which, while not comprehen- sive, has the advantage of including postal markings as By Len McMaster well as early postmasters6. Previously I discussed a little of the history of Hamp- Thus I have attempted to identify the approximate shire County, described the source of the data and the location and dates of operation of the post offices es- conventions used in the listings, and began the listing of tablished in Hampshire County, explaining, where pos- the post offices from Augusta through Green Valley sible, the discrepancies or possible confusion that ex- Depot. The introduction is repeated here. ists in the other listings. Because of the length of the material, it has been broken up into three parts. This Introduction part will include the balance of the Hampshire county Several people have previously cataloged the Hamp- post office descriptions starting with Hainesville, and shire County West Virginia post offices, generally as the third part will include descriptions of the post of- part of a larger effort to list all the post offices of West fices in Mineral County today that were established in Virginia. Examples include Helbock’s United States Post Hampshire County before Mineral County was split off, Offices1 and Small’s The Post Offices of West Vir- and tables of all the post offices established in Hamp- ginia, 1792-19772. Confusing this study is that Hamp- shire County. shire County was initially split off from Virginia with Individual Post Office Location the establishment of many early post offices appearing in studies of Virginia post offices such as Abelson’s and History of Name Changes 3 Virginia Postmasters and Post Offices, 1789-1832 Hainesville (Haines Store) and Hall’s “Virginia Post Offices, 1798-1859”4; and that Hampshire County was itself eventually split into all or Hainesville was located near the crossroads of Old parts of five West Virginia counties, including its present Martinsburg Road (County Route 45/9) and Kedron day boundaries. -

Hampshire Country Club Planned Residential Development Village of Mamaroneck, Westchester County, New York

Final Environmental Impact Statement Hampshire Country Club Planned Residential Development Village of Mamaroneck, Westchester County, New York LEAD AGENCY Village of Mamaroneck Planning Board 169 Mt Pleasant Avenue, Third Floor Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Contact: Village of Mamaroneck Planning Department 914.825.8758 PREPARED BY VHB Engineering, Surveying, and Landscape Architecture, P.C. 50 Main Street Suite 360 White Plains, NY 10606 914.617.6600 The Chazen Companies 1 North Broadway, Suite 803 White Plains, New York 10601 845-454-3980 Abrams Fensterman, LLP 81 Main Street, Suite 306 White Plains, New York 10601 914-607-7010 Village of Mamaroneck Planning Board 169 Mount Pleasant Avenue Mamaroneck, New York 10543 914-825-8757 Date of Adoption April 6, 2020 Lead Agency: Village of Mamaroneck Planning Board 169 Mount Pleasant Avenue Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Contact: Betty-Ann Sherer, Land Use Coordinator (914) 825-8758 [email protected] Applicant: Hampshire Recreation, LLC c/o New World Realty Advisors, LLC 60 Cutter Mill Road, Ste. 513 Great Neck, NY 11021 Contact: Dan Pfeffer (646) 723-4750 [email protected] Consultants that contributed to this document include: Project Attorney: Zarin & Steinmetz 81 Main Street, Suite 415 White Plains, NY 10601 Contact: David J. Cooper, Esq. (914) 682-7800 [email protected] Planning/EIS Preparation/Traffic Engineering/Natural Resources/Cultural Resources, Site Engineering, Architecture Landscape Design: VHB Engineering, Surveying, and Landscape Architecture, P.C. 50 Main Street, Suite 360 White Plains, NY 10606 Contact: Valerie Monastra, AICP (914) 467-6600 [email protected] Site Engineering, Traffic Engineering: Kimley-Horn 1 North Lexington Avenue, Suite 1575 White Plains, NY 10601 Contact: Michael Junghans, PE (914) 368-9200 [email protected] Geotechnical Engineering, Environmental Services: GZA 104 West 29th Street, 10th Floor New York, NY 10001 Contact: Stephen M. -

Ordinance 16267

I KING COUNTY 1200 King County Courthouse 516 Third Avenue tl Seattle, WA 98104 King County Signature Report October 9, 2008 Ordinance 16267 Proposed No. 2008-0128.2 Sponsors Gossett AN ORDINANCE relating to zoning and development. 2 regulations; amending Ordinance 1488, Section 2, as 3 amended, and K.C.C. 16.82.010, Ordinance 1488, Section 4 5, as amended, and K.C.C. 16.82.020, Ordinance 15053, 5 Section 3, and K.C.C. 16.82.051, Ordinance 14259, Section 6 4, and K.C.C. 16.82.052, Ordinance 1488, Section 11, as 7 amended, and K.C.C. 16.82.100, Ordinance 9614, Section 8 103, as amended, and K.C.C. 16.82.150, Ordinance 15053, 9 Section 15, and K.C.C. 16.82.152, Ordinance 13694, 10 Section 51, and K.C.C. 19A.08.160, Ordinance 13694, 11 Section 52, and K.C.C. 19A.08.170, Ordinance 10870, 12 Section 138, as amended, and K.C.C. 21A.06.490, 13 Ordinance 15051, Section 64, and K.C.C. 21A.06.578, 14 Ordinance 10870, Section 259, and K.C.C. 21A.06.1095, 15 Ordinance 15051, Section 86, and K.C.C. 21A.06.942, 16 Ordinance 15051, Section 100, and K.C.C. 21A.06.1182, 17 Ordinance 10870, Section 297, and K.C.C. 21A.06.1285, Ordinance 16267 18 Ordinance 10870, Section 330, as amended, and K.C.C. 19 21A.08.030, Ordinance 10870, Section 331, as amended, 20 and K.C.C. 21A.08.040, Ordinance 10870, Section 332, as 21 amended, and K.C.C. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

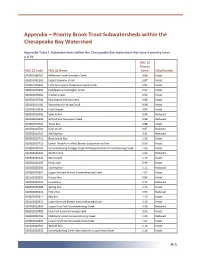

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Armstrong County.Indd

COMPREHENSIVE RECREATION, PARK, OPEN SPACE & GREENWAY PLAN Conservation andNatural Resources,Bureau ofRecreation andConservation. Keystone Recreation, ParkandConservationFund underadministrationofthe PennsylvaniaDepartmentof This projectwas June 2009 BRC-TAG-12-222 fi nanced inpartbyagrantfrom theCommunityConservation PartnershipsProgram, The contributions of the following agencies, groups, and individuals were vital to the successful development of this Comprehensive Recreation, Parks, Open Space, and Greenway Plan. They are commended for their interest in the project and for the input they provided throughout the planning process. Armstrong County Commissioners Patricia L. Kirkpatrick, Chairman Richard L. Fink, Vice-Chairman James V. Scahill, Secretary Armstrong County Department of Planning and Development Richard L. Palilla, Executive Director Michael P. Coonley, AICP - Assistant Director Sally L. Conklin, Planning Coordinator Project Study Committee David Rupert, Armstrong County Conservation District Brian Sterner, Armstrong County Planning Commission/Kiski Area Soccer League Larry Lizik, Apollo Ridge School District Athletic Department Robert Conklin, Kittanning Township/Kittanning Township Recreation Authority James Seagriff, Freeport Borough Jessica Coil, Tourist Bureau Ron Steffey, Allegheny Valley Land Trust Gary Montebell, Belmont Complex Rocco Aly, PA Federation of Sportsman’s Association County Representative David Brestensky, South Buffalo Township/Little League Rex Barnhart, ATV Trails Pamela Meade, Crooked Creek Watershed -

Legal Notice

Ticket Taxpayer(s) Legal Description Sold To Amount LEGAL NOTICE List of tax liens sold in the County of HAMPSHIRE on the 10th day of November, 2015 for the nonpayment of taxes thereon for the year 2014, and purchased by individuals or certified to the Auditor of the State of West Virginia: 01-BLOOMERY 143 BAKER DONALD & N RIVER DRS 5.645 AC ROBERT & LOIS GROVES 9,400.00 HOLLIDAY DELLA MAXINE ON REDSTONE RD NEAR VA LINE PO BOX 308 ROMNEY WV 26757-0308 529 CHUN PYONG HUI 5.00 AC LOT 22 FAT KITTY PROPERTIES, LLC 2,600.00 OAK FOREST SD 709 N EDGEWOOD ST ARLINGTON VA 22201-1933 627 COWGILL DELILAH E (RAIGNER) .09 AC CAPON DRS 3700 SQ FT LAG REALTY DEVELOPMENT & HOLDING LLC 92.38 5823 CARPERS PIKE YELLOW SPRING WV 26865 774 DEWEIN CHRISTOPHER E & LOT 34 2.023 AC HARDY COUNTY HOLDINGS 600.00 JERAVEE H DEWEIN STAGECOACH STOP @ CAPON BRIDGE 145 CYPRESS POINT PKY UNIT 202 PALM COAST FL 32164-8427 794 DOLBY LAWRENCE B & COLLEEN D .856AC LOT 83-84-85 FAT KITTY PROPERTIES, LLC 2,500.00 CACAPON RIVER RECREATION AREA 709 N EDGEWOOD ST ARLINGTON VA 22201-1933 795 DOLBY LAWRENCE B & COLLEEN D .858AC LOT 86-87 FAT KITTY PROPERTIES, LLC 3,000.00 CACAPON RIVER RECREATION AREA 709 N EDGEWOOD ST ARLINGTON VA 22201-1933 903 EWING EUGENE W & ROSE M & EAGLE MOUNTAIN SD 10.50 AC FAT KITTY PROPERTIES, LLC 4,200.00 WALTER ARTHUR EWING LOT 10-B 709 N EDGEWOOD ST ARLINGTON VA 22201-1933 1040 GABRIEL WALTER C 1.14 AC OWL HOLLOW RD ROBERT & LOIS GROVES 1,100.00 CCC W/PCL 118 PO BOX 308 ROMNEY WV 26757-0308 1060 GAUG ROBERT A & JOAN SPRING GAP SD 5.09 AC HARDY COUNTY -

Commutation Tickets New Register Members, South

•V S BANK! REGISTER; T1 VfVti ' lllusd W««kl>' EnUred as aVond-Glass ttaittr *<• Iba Post- ij ALV11, oOct il B«r] Bink, N K uDder tb* Act ol^larob Id. 1«1». RED %%W, N,,,J., WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 14,1925, • $1.50 PER.YEAR. PAGES 1 TO 8$ HIGH SCHOOL RECEPTION. HOLMDEL SLED COASTERS. COMMUTATION TICKETS NEW REGISTER MEMBERS, ieventh Grade Pupilt to bs Cuette SOUTH RED BANK-PARTY. [0T£ MADE FOR $40,01)0 un and Curioui Miihapi on Koer.t A BIGGER SHOW IN 1925. FIGURING OUT WORDSJI • of Senior Clan. Heyer'i Hill. SUMMEft RESIDENTS ASK FOR IN REG- EW PART OF TOWN HAS COM- IDDLETOWN TOWNSHIP RUN- HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY IS •IFTY TAKE PART IN CROSS*' ISTER'S OFFICIAL FAMILY. The senior class of the lied Bank MUNITY, DANCE. NING SHORT OF MONEY. flld' folks as well as young folks MAKING PLANS ALREADY. •"- LOWER RA;LROAD RATES. igh school will hold its annual re- iavo been enjoying sled coasting at ORD CONTEST AT tlNCROFT* -Say It Would Be Ruin- hay Art John S. Valentine, Carl ;ption for the members, of the Matthew Shnota Wa» the Host and The School Board Applied for lolmdel on . the "hill' on Koert The Newly-Elected Officer* of tie Thli Wat tha Main Fe.tur. 'Voui (or Them 'to laiui Short Tarm H. Winters and Cecil R. Mae- eventh gr&do on Friday night of He Played the; Part to "the $45,000 and the Township Com- Jeyor's farm. Tho sport goes on Society Were Installed Lait Community Gathering at tho| '•' 7 Commutation TlelceM at the Same Clone!, Each of Whom Ha* hit week at the junior high school Queen'* Taiie" in Hit Bit New mittee Provided $40,009 by Put- lay afid night. -

Total Employment by State, Class of Employer and Last Railroad Employer Calendar Year 2014

Statistical Notes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | U.S. Railroad Retirement Board Bureau of the Actuary www.rrb.gov No. 3 - 2016 May 2016 Total Employment by State, Class of Employer and Last Railroad Employer Calendar Year 2014 The attached table shows total employment by State, class of employer and last railroad employer in the year. Total employment includes all employees covered by the Railroad Retirement and Railroad Unemployment Insurance Acts who worked at least one day during calendar year 2014. For employees shown under Unknown for State, either no address is on file (0.7 percent of all employees) or the employee has a foreign address such as Canada (0.2 percent). TOTAL EMPLOYMENT BY STATE, CLASS OF EMPLOYER AND LAST RAILROAD EMPLOYER CALENDAR YEAR 2014 CLASS OF STATE EMPLOYER1 RAILROAD EMPLOYER NUMBER Unknown 1 BNSF RAILWAY COMPANY 4 Unknown 1 CSX TRANSPORTATION INC 2 Unknown 1 DAKOTA MINNESOTA & EASTERN RAILROAD CORPORATION 1 Unknown 1 DELAWARE AND HUDSON RAILWAY COMPANY INC 1 Unknown 1 GRAND TRUNK WESTERN RAILROAD COMPANY 1 Unknown 1 ILLINOIS CENTRAL RR CO 8 Unknown 1 NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORP (AMTRAK) 375 Unknown 1 NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION 9 Unknown 1 SOO LINE RAILROAD COMPANY 2 Unknown 1 UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMPANY 3 Unknown 1 WISCONSIN CENTRAL TRANSPORTATION CORP 1 Unknown 2 CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY COMPANY 66 Unknown 2 IOWA INTERSTATE RAILROAD LTD 64 Unknown 2 MONTANA RAIL LINK INC 117 Unknown 2 RAPID CITY, PIERRE & EASTERN RAILROAD, INC 21 Unknown 2 -

Potomac Basin Comprehensive Water Resources Plan

One Basin, One Future Potomac River Basin Comprehensive Water Resources Plan Prepared by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin - 2018 - Dedication i VISION This plan provides a roadmap to achieving our shared vision that the Potomac River basin will serve as a national model for water resources management that fulfills human and ecological needs for current and future generations. The plan will focus on sustainable water resources management that provides the water quantity and quality needed for the protection and enhancement of public health, the environment, all sectors of the economy, and quality of life in the basin. The plan will be based on the best available science and data. The ICPRB will serve as the catalyst for the plan's implementation through an adaptive process in collaboration with partner agencies, institutions, organizations, and the public. Dedication ii DEDICATION This plan is dedicated to Herbert M. Sachs, an ICPRB Maryland Commissioner and Executive Director. He also served for decades with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the Department of the Environment. He passed away in 2017. During his nearly 30-year tenure of service to ICPRB, Sachs led the agency’s efforts in supporting the regional Chesapeake Bay Program; reallocation of water supplies, cooperative law enforcement, and water quality efforts at Jennings Randolph Reservoir; and establishment of the North Brach Potomac Task Force, a group of stakeholders and officials facilitated by ICPRB that gives stakeholders a voice in management decisions. He also was at the helm when ICPRB embarked on its successful effort to restore American shad to the Potomac River. -

Trains 2015 Index

INDEX TO VOLUME 75 Reproduction of any part of this volume for commercial pur poses is not allowed without the specific permission of the publishers. All contents © 2014 and 2015 by Kalmbach Publishing Co., Wau kesha, Wis. JANUARY 2015 THROUGH DECEMBER 2015 – 946 PAGES HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article are not separately indexed. Brief news items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category; news stories are indexed under the appro- priate railroad and/or category and under the author’s last name. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are easily identified; if there is no easy identification, they may be indexed under the person’s last name (for deaths, see “Obit uaries”). Maps, museums, radio frequencies, railroad historical societies, rosters of locomotives and equipment, product reviews, and stations are indexed under these categories. Items from countries other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country. A Amtrak reaffirms late 2015 PTC completion date, Abbe, Elfrieda, articles by: Aug 7 Lincoln Funeral Car revival, Jun 50-55 Amtrak revises Guest Rewards in 2016, Passenger, Lincoln Funeral Train project is on track for national Nov 34-35 tour in 2015, Preservation, Feb -

Armstrong County Comprehensive Plan

ARMSTRONG COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN APRIL 2005 Armstrong County Comprehensive Plan ARMSTRONG COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................1 A. Housing .....................................................................................................................1 B. Economic Development ............................................................................................2 C. Transportation...........................................................................................................3 D. Recreation / Open Space / Natural Resources.........................................................4 E. Public Utilities / Services / Facilities..........................................................................4 F. Land Use...................................................................................................................5 G. References................................................................................................................5 2. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................9 3. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................11 A. What is the Purpose of a Comprehensive Plan ......................................................11 B. Planning Process and Citizen Participation ............................................................11 C. Statement of Objectives..........................................................................................13