Turkish Language As a Politicized Element: the Case of Turkish Nation-Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

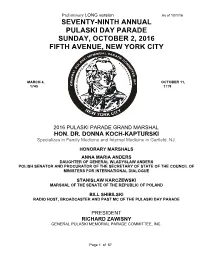

Seventy-Ninth Annual Pulaski Day Parade Sunday, October 2, 2016 Fifth Avenue, New York City

Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 SEVENTY-NINTH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY MARCH 4, OCTOBER 11, 1745 1779 2016 PULASKI PARADE GRAND MARSHAL HON. DR. DONNA KOCH-KAPTURSKI Specializes in Family Medicine and Internal Medicine in Garfield, NJ. HONORARY MARSHALS ANNA MARIA ANDERS DAUGHTER OF GENERAL WLADYSLAW ANDERS POLISH SENATOR AND PROCURATOR OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS FOR INTERNATIONAL DIALOGUE STANISLAW KARCZEWSKI MARSHAL OF THE SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND BILL SHIBILSKI RADIO HOST, BROADCASTER AND PAST MC OF THE PULASKI DAY PARADE PRESIDENT RICHARD ZAWISNY GENERAL PULASKI MEMORIAL PARADE COMMITTEE, INC. Page 1 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 ASSEMBLY STREETS 39A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. M A 38 FLOATS 21-30 38C FLOATS 11-20 38B 38A FLOATS 1 - 10 D I S O N 37 37C 37B 37A A V E 36 36C 36B 36A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. Page 2 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE 79TH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE COMMEMORATING THE SACRIFICE OF OUR HERO, GENERAL CASIMIR PULASKI, FATHER OF THE AMERICAN CAVALRY, IN THE WAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE BEGINS ON FIFTH AVENUE AT 12:30 PM ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016. THIS YEAR WE ARE CELEBRATING “POLISH- AMERICAN YOUTH, IN HONOR OF WORLD YOUTH DAY, KRAKOW, POLAND” IN 2016. THE ‘GREATEST MANIFESTATION OF POLISH PRIDE IN AMERICA’ THE PULASKI PARADE, WILL BE LED BY THE HONORABLE DR. DONNA KOCH- KAPTURSKI, A PROMINENT PHYSICIAN FROM THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY. -

An Etymological and Lexicological Note on the Words for Some Ancient Eurasian Grain Legume Crops in Turkic Languages

Turkish Journal of Field Crops, 2011, 16(2): 179-182 AN ETYMOLOGICAL AND LEXICOLOGICAL NOTE ON THE WORDS FOR SOME ANCIENT EURASIAN GRAIN LEGUME CROPS IN TURKIC LANGUAGES Aleksandar MIKIĆ1* Vesna PERIĆ2 1Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops, Serbia 2Maize Research Institute Zemun Polje, Serbia *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Received: 06.07.2011 ABSTRACT On their way to both Europe and Caucasus, during the 7th and 6th millennia BC, the most ancient Old World grain legume crops, such as pea (Pisum sativum L.), lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) and faba bean (Vicia faba L.), passed through the region of modern Turkey but also spread towards the original Altaic, and then, Turkic homeland. The assumption that at least some of these crops were known to the ancestors of the modern Turkic nations is confirmed by attesting the Proto-Altaic *bŭkrV, denoting pea and its descendant the Proto-Turkic *burčak, being responsible for all the words denoting pea in the majority of the modern Turkic languages and the borrowed Hungarian borsó. The Proto-Altaic root *zịăbsa, denoting lentil, gave the Proto-Turkic, *jasi-muk, with the same meaning and with numerous, morphologically well-preserved descendants in modern Turkic languages. Key words: Etymology, grain legumes, lexicology, Turkic languages. INTRODUCTION uncertain origin (Georg et al. 1999) and still disputed by some as being true Altaic languages. Majority of the traditional Eurasian grain legume crops, such as pea (Pisum sativum L.) and lentil (Lens culinaris The supporters of the existence of the Altaic language Medik.) originated in the Near Eastern centre of diversity, family assumed that its five branches had a common ancestor while faba bean (Vicia faba L.) originated in the central referred to as Proto-Altaic, although the written records on its Asian centre of diversity (Zeven and Zhukovsky 1975). -

Social Engineering’

European Journal of Turkish Studies Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey 7 | 2008 Demographic Engineering - Part I Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk ‘Social Engineering’ Uğur Ümit Üngör Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejts/2583 DOI: 10.4000/ejts.2583 ISSN: 1773-0546 Publisher EJTS Electronic reference Uğur Ümit Üngör, « Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk ‘Social Engineering’ », European Journal of Turkish Studies [Online], 7 | 2008, Online since 05 March 2015, connection on 16 February 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejts/2583 ; DOI : 10.4000/ejts. 2583 © Some rights reserved / Creative Commons license Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2008) 'Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk ‘Social Engineering’', European Journal of Turkish Studies, Thematic Issue N° 7 , No. 7 | Demographic Engineering - part I, URL : http://www.ejts.org/document2583.html To quote a passage, use paragraph (§). Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk ‘Social Engineering’ Uğur Ümit Üngör Abstract. This article addresses population politics in the broader Young Turk era (1913-1950), which included genocide, deportation, and forced assimilation of various minority populations. The article opens with an account of the genesis of the concept ‘social engineering’ and provides a synopsis of the literature in the field of Young Turk population politics. It then focuses on the implementation of these nationalist population politics in the eastern provinces to exemplify these policies in detail. The article aims to clarify that the Armenian genocide cannot be understood in isolation from broader Young Turk population politics and argues that a generation of traumatized Young Turk politicians launched and perpetuated this violent project of societal transformation in order to secure the existence of a Turkish nation-state. -

The Launching of the Turkish Thesis of History: a Close Textual Analysis

THE LAUNCHING OF THE TURKISH THESIS OF HISTORY: A CLOSE TEXTUAL ANALYSIS by CEREN ARKMAN SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY SABANCI UNIVERSITY FEBRUARY 2006 THE LAUNCHING OF THE TURKISH THESIS OF HISTORY: A CLOSE TEXTUAL ANALYSIS MEMBERS OF THE EXAMINATION COMMITEE: Prof. Halil Berktay (Thesis Supervisor) Assistant Prof. Ali Çarko ğlu Assistant Prof. Yusuf Hakan Erdem DATE OF APPROVAL: © CEREN ARKMAN February 2006 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT THE LAUNCHING OF THE TURKISH THESIS OF HISTORY: A CLOSE TEXTUAL ANALYSIS CEREN ARKMAN M.A. in History February 2006 Thesis Supervisor: Prof Halil Berktay Keywords: nationalism, history, Turkey The following is a dissertation on the Turkish Thesis of History, focusing specifically on a certain instant in its development, namely the First Turkish History Congress in which the Thesis was fully formulated. Taking its lead from the ideas of Benedict Anderson, the dissertation is based on the assumption that the nations are imagined cultural constructs; and that it is primarily the style in which it is imagined that gives a nation its distinctive character. Developing these ideas, the work turns its attention to the methods of such imagination and incorporating the ideas of Anthony D. Smith on national myths, devises a conceptual framework for making sense of the interrelations among the formation of nations, the writing of national histories and the creation of national myths. In light of this theoretical framework, the papers of the Congress are analyzed in detail in order to trace clues of the distinctive characteristics of Turkish nationalism –its peculiarities which were to a large extent dictated by the limits (real or imagined) in reaction to which Turkish nationalism developed. -

Atatürk and Turkish Language Reform

ATATÜRK AND TURKISH LANGUAGE REFORM F A H İR İZ* Language Reform is one of the most controversial issues of contem- porary Turkey. Essentially a cultural even a scientifıc problem which, one vvould ex- pect, to be handled or studied only by experts, it tended in recent deca- des, to become increasingly involved vvith political issues. So much so that almost anyone who is interested in the problems of Modem Turkey in general, is tempted to join the controversy, often with emotional partisan- ship. Although its origins are rooted, as we shall see, in the fundamental cultural cahange of a thousand years ago and remained alive through the centuries of the evolution of the Turkish language, some Turkish vvriters and quite a few foreign scholars (turcologists or others) surprisingly consi- der this movement just as anyone of the series of Reforms of the Repub- lican era. Some even go so far as believing it to be nothing but a “capri- cious” enterprise of Atatürk or a nevv-fangled idea put forvvard by the Turkish Linguistic Society founded by him. It is also true that some vvri ters change their approach to the problem according to the political cli- mate, proving further that it is not easy for them to be unbiased on this issue. This is most unfortunate, because Turkish Language Reform is essen tially a cultural phenomenon vvhich should have nothing to do vvith con- temporary politics. The need for a reform in a language may have many diverse causes. But the classical example of language reform, as vvitnessed in the histories of the German, Hungarian, Finnish and Norvvegian languages for instan- ce, appear to be the result of a reaction againts an unreasonable overflovv of foreign elements in the vvritten language, making it virtually unintelli- gible to ordinary speakers of that language. -

Kurdish Language Rights and Mother Tounge in Education

KURDISH LANGUAGE RIGHTS AND MOTHER TONGUE IN EDUCATION Esra Çevik Language In his 1985 work '' Anathemas and Admirations'', Emil Cioran, a Romanian philosopher and essayist, wrote that ''one does inhabit a country; one inhabits a language. That is our country, our fatherland and no other.'' For Kurds - as many other nations – language is one of the most important points for both individuals and society. Language plays a major role in the shaping of an individual’s identity and its social integration. Throughout history, languages have been used for political purposes, most often as a tool used to build identities and bring together a group of people. As language has both a symbolic and instrumental value, nation-states intervene [in its development] in order to ensure that [social integration] takes place along the desired path. Languages are managed, guided and even re-created. And a number of mechanisms are employed to ensure that the national language is spread. With this aim, tate activities are often held in a single language and the chosen language is imposed to the people of that country who speak different languages. When looking at languages, language policies and rights should be addressed together, because they interact with each other both on a national and international level and they also influence individuals’ language behaviour.1 1 Virtanen, Dil Politikalarının Milliyetçilik Hareketlerindeki Tarihsel Kökenleri, 18. Language policies can be defined as a totality of principles, decisions and practices concerning the languages used within a particular political unit, their areas and regions, their development and the rights to their use.2 Turkey was never an ethnically homogenous country, but leaderships developed definition for the nation that excluded multi-ethnicity. -

Lilo Linke a 'Spirit of Insubordination' Autobiography As Emancipatory

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ autobiography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/177/ Version: Full Version Citation: Ogurla, Anita Judith (2016) Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ auto- biography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Lilo Linke: A ‘Spirit of Insubordination’ Autobiography as Emancipatory Pedagogy; A Turkish Case Study Anita Judith Ogurlu Humanities & Cultural Studies Birkbeck College, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, February 2016 I hereby declare that the thesis is my own work. Anita Judith Ogurlu 16 February 2016 2 Abstract This thesis examines the life and work of a little-known interwar period German writer Lilo Linke. Documenting individual and social evolution across three continents, her self-reflexive and autobiographical narratives are like conversations with readers in the hope of facilitating progressive change. With little tertiary education, as a self-fashioned practitioner prior to the emergence of cultural studies, Linke’s everyday experiences constitute ‘experiential learning’ (John Dewey). Rejecting her Nazi-leaning family, through ‘fortunate encounter[s]’ (Goethe) she became critical of Weimar and cultivated hope by imagining and working to become a better person, what Ernst Bloch called Vor-Schein. Linke’s ‘instinct of workmanship’, ‘parental bent’ and ‘idle curiosity’ was grounded in her inherent ‘spirit of insubordination’, terms borrowed from Thorstein Veblen. -

Turkish Nationalism and Turkish Islam: a New Balance

TURKISH NATIONALISM AND TURKISH ISLAM: A NEW BALANCE Nationalism and Islam have widely tended to be viewed as separate elements in the Turkish context. However, Islam has, in fact, been a foundational part of Turkish identity since the establishment of the Turkish Republic; and, on the popular level, Islam cannot actually be separated from nationalism. The equation of Turkish with Muslim identity was always tacitly understood; now it is explicit. Previous Turkish governments have, at times, won support by ap- pealing to both nationalist and religious sentiments as well but none has done this so successfully as the AKP… The current Turkish government’s rhetoric manages to appeal to both impulses, and that is why it is such a powerful brew. The AKP has been able to achieve what no other government has be- fore: wedding popular religious nationalism to the levers of government and remaining in power whilst doing so. William Armstrong* * William Armstrong is a freelance journalist and editor, currently working in İstanbul. 133 VOLUME 10 NUMBER 4 WILLIAM ARMSTRONG ince the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, received wisdom has tended to consider nationalism and Islam as mutually incompatible forces in the Turkish context. Turkish nationalism – S so this narrative goes - is defined by the secularizing, modernizing example of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a positivist, military man with an almost religious faith in the ability of science to reshape society. Islam, with its appeals to multinational, multiracial unity, inevitably stood in the way of the “pure”, homogenous nation-state. Such an understanding was propagated by those early secularizing elites within Turkey itself, and largely accepted by observers outside the country for the better part of the past hundred years. -

11 Lewis 1749.Indd

GEOFFREY LEWIS Geoffrey Lewis Lewis 1920–2008 I. Life PROFESSOR GEOFFREY LEWIS LEWIS, a pioneer in Turkish Studies in Britain and an internationally admired scholar in the fi eld, was born in London on 19 June 1920. He received his schooling at University College School in Hampstead, following which, in 1938, he went up to St John’s College Oxford to read Classics. Having sat Honour Moderations in the spring of 1940, he joined the Royal Air Force in September of that year and served until 1945: he qualifi ed for his BA by War Decree and subsequently received his MA in 1945. At some point during his study for Honour Mods, his Latin tutor, sensing that he was getting stale, suggested that he take up Turkish as a hobby—it seems that the choice of Turkish came to him on the spur of the moment. Geoffrey took it seriously, however, and the opportunity to act on it came when he was posted to Egypt as a radar operator. He made contact with an elderly Turk in Alexandria, through whom, and through the painstaking comparison of classic English texts with their Turkish translations—these culled from the bookshops of London and sent to him by his wife, Raphaela, whom he had married in 1941—he taught him- self Turkish. Returning to Oxford in 1945, and by now wholly won over to Turkish, he consulted the Laudian Professor of Arabic, [Sir] Hamilton Gibb, FBA, who welcomed the prospect of expanding the curriculum in Oriental Studies to include Turkish but recommended that Geoffrey read for the BA in Arabic and Persian as essential background to the serious study of Turkish historically as well as in its modern form. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator. -

52927457.Pdf

THE CULTURAL POLICIES OF THE TURKISH REPUBLIC DURING THE ESTABLISHMENT OF NATION STATE (1923- 1938) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by iPEK KAMACI Io Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of MASTER OF ARTS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION in THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February,2000 The.sis bf )30 , K.3' .2t;oo .E,c50.c;\O I certify that l have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a th~sis for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science and Public Administrati n. Assistant Professor Orhan Tekelioglu l certify that l have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science and Public Administration. I certify that I have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science and Public Administration. Dr.Me Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Ali Karaosmanoglu ABSTRACT THE CULTURAL POLICIES OF THE TURKISH REPUBLIC DURING THE ESTABLISHMENT OF NATION STA TE (1923 - 1938) ipek KAMACI Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor: Asst. Prof Orhan TEKEUOGLU February, 2000 This study aims to analyse the understanding of cultural politics during the establishment period of Turkish Republic. It is argued that this understanding of culturai politics is ideologically shaped by Kemalism that maintains Ziya Gokalp's separation of culture and civilization. -

Capital Flows and Reversals in Europe, 1919-32 Olivier Accominotti and Barry Eichengreen NBER Working Paper No

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE MOTHER OF ALL SUDDEN STOPS: CAPITAL FLOWS AND REVERSALS IN EUROPE, 1919-32 Olivier Accominotti Barry Eichengreen Working Paper 19580 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19580 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2013 Olivier Accominotti thanks the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University for hosting him during the preliminary phase of this project and the librarians at the Mudd Manuscript Library for their support. The authors thank Stefano Battilossi, Vincent Bignon, Rui Esteves, Marc Flandreau, Harold James, Leandro Prados de la Escosura, Albrecht Ritschl, Peter Temin, Stefano Ugolini, Jeff Williamson, participants at the CEPR Economic History Symposium in Perugia, at the Monetary History Group seminar at Rothschild and at seminars at Universidad Carlos III Madrid and Australian National University for helpful comments. We also thank Jef Boeckx and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti for sharing data and advice on Eurozone countries’ balance of payment statistics, and Marc Flandreau and Norbert Gaillard for sharing the ratings data. All remaining errors are ours. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2013 by Olivier Accominotti and Barry Eichengreen. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source.