Dmitri Tymoczko Princeton University [email protected] June 20, 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day 17 AP Music Handout, Scale Degress.Mus

Scale Degrees, Chord Quality, & Roman Numeral Analysis There are a total of seven scale degrees in both major and minor scales. Each of these degrees has a name which you are required to memorize tonight. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 & w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic A triad can be built upon each scale degree. w w w w & w w w w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic The quality and scale degree of the triads is shown by Roman numerals. Captial numerals are used to indicate major triads with lowercase numerals used to show minor triads. Diminished triads are lowercase with a "degree" ( °) symbol following and augmented triads are capital followed by a "plus" ( +) symbol. Roman numerals written for a major key look as follows: w w w w & w w w w w w w w CM: wI (M) iiw (m) wiii (m) IV (M) V (M) vi (m) vii° (dim) I (M) EVERY MAJOR KEY FOLLOWS THE PATTERN ABOVE FOR ITS ROMAN NUMERALS! Because the seventh scale degree in a natural minor scale is a whole step below tonic instead of a half step, the name is changed to subtonic, rather than leading tone. Leading tone ALWAYS indicates a half step below tonic. Notice the change in the qualities and therefore Roman numerals when in the natural minor scale. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

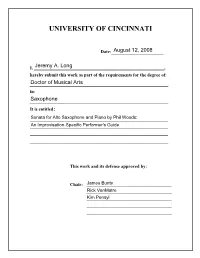

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods. -

The Romantext Format: a Flexible and Standard Method for Representing Roman Numeral Analyses

THE ROMANTEXT FORMAT: A FLEXIBLE AND STANDARD METHOD FOR REPRESENTING ROMAN NUMERAL ANALYSES Dmitri Tymoczko1 Mark Gotham2 Michael Scott Cuthbert3 Christopher Ariza4 1 Princeton University, NJ 2 Cornell University, NY 3 M.I.T., MA 4 Independent [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Absolute chord labels are performer-oriented in the sense that they specify which notes should be played, but Roman numeral analysis has been central to the West- do not provide any information about their function or ern musician’s toolkit since its emergence in the early meaning: thus one and the same symbol can represent nineteenth century: it is an extremely popular method for a tonic, dominant, or subdominant chord. Accordingly, recording subjective analytical decisions about the chords these labels obscure a good deal of musical structure: a and keys implied by a passage of music. Disagreements dominant-functioned G major chord (i.e. G major in the about these judgments have led to extensive theoretical de- local key of C) is considerably more likely to descend by bates and ongoing controversies. Such debates are exac- perfect fifth than a subdominant-functioned G major (i.e. G erbated by the absence of a public corpus of expert Ro- major in the key of D major). This sort of contextual in- man numeral analyses, and by the more fundamental lack formation is readily available to both trained and untrained of an agreed-upon, computer-readable syntax in which listeners, who are typically more sensitive to relative scale those analyses might be expressed. This paper specifies degrees than absolute pitches. -

Graduate Music Theory Exam Preparation Guidelines

Graduate Theory Entrance Exam Information and Practice Materials 2016 Summer Update Purpose The AU Graduate Theory Entrance Exam assesses student mastery of the undergraduate core curriculum in theory. The purpose of the exam is to ensure that incoming graduate students are well prepared for advanced studies in theory. If students do not take and pass all portions of the exam with a 70% or higher, they must satisfactorily complete remedial coursework before enrolling in any graduate-level theory class. Scheduling The exam is typically held 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m. on the Thursday just prior to the start of fall semester classes. Check with the Music Department Office for confirmation of exact dates/times. Exam format The written exam will begin at 8:00 with aural skills (intervals, sonorities, melodic and harmonic dictation) You will have until 10:30 to complete the remainder of the written exam (including four- part realization, harmonization, analysis, etc.) You will sign up for individual sight-singing tests, to begin directly after the written exam Activities and Skills Aural identification of intervals and sonorities Dictation and sight-singing of tonal melodies (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate both pitch and rhythm. Dictation of tonal harmonic progressions (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate soprano, bass, and roman numerals. Multiple choice Short answer Realization of a figured bass (four-part voice leading) Harmonization of a given melody (four-part voice leading) Harmonic analysis using roman numerals 1 Content -

Affordant Chord Transitions in Selected Guitar-Driven Popular Music

Affordant Chord Transitions in Selected Guitar-Driven Popular Music Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gary Yim, B.Mus. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: David Huron, Advisor Marc Ainger Graeme Boone Copyright by Gary Yim 2011 Abstract It is proposed that two different harmonic systems govern the sequences of chords in popular music: affordant harmony and functional harmony. Affordant chord transitions favor chords and chord transitions that minimize technical difficulty when performed on the guitar, while functional chord transitions favor chords and chord transitions based on a chord's harmonic function within a key. A corpus analysis is used to compare the two harmonic systems in influencing chord transitions, by encoding each song in two different ways. Songs in the corpus are encoded with their absolute chord names (such as “Cm”) to best represent affordant factors in the chord transitions. These same songs are also encoded with their Roman numerals to represent functional factors in the chord transitions. The total entropy within the corpus for both encodings are calculated, and it is argued that the encoding with the lower entropy value corresponds with a harmonic system that more greatly influences the chord transitions. It is predicted that affordant chord transitions play a greater role than functional harmony, and therefore a lower entropy value for the letter-name encoding is expected. But, contrary to expectations, a lower entropy value for the Roman numeral encoding was found. Thus, the results are not consistent with the hypothesis that affordant chord transitions play a greater role than functional chord transitions. -

Choir I: Diatonic Chords in Major and Minor Keys May 4 – May 8 Time Allotment: 20 Minutes Per Day

10th Grade Music – Choir I: Diatonic Chords in Major and Minor Keys May 4 – May 8 Time Allotment: 20 minutes per day Student Name: ________________________________ Teacher Name: ________________________________ Academic Honesty I certify that I completed this assignment I certify that my student completed this independently in accordance with the GHNO assignment independently in accordance with Academy Honor Code. the GHNO Academy Honor Code. Student signature: Parent signature: ___________________________ ___________________________ Music – Choir I: Diatonic Chords in Major and Minor Keys May 4 – May 8 Packet Overview Date Objective(s) Page Number Monday, May 4 1. Review Roman numeral identification of triads 2 2. Identify diatonic seventh chords in major Tuesday, May 5 1. Identify diatonic seventh chords in minor 4 Wednesday, May 6 1. Decode inversion symbols for diatonic triads 5 Thursday, May 7 1. Decode inversion symbols for diatonic seventh 7 chords Friday, May 8 1. Demonstrate understanding of diatonic chord 9 identification and Roman numeral analysis by taking a written assessment. Additional Notes: In order to complete the tasks within the following packet, it would be helpful for students to have a piece of manuscript paper to write out triads; I have included a blank sheet of manuscript paper to be printed off as needed, though in the event that this is not feasible students are free to use lined paper to hand draw a music staff. I have also included answer keys to the exercises at the end of the packet. Parents, please facilitate the proper use of these answer documents (i.e. have students work through the exercises for each day before supplying the answers so that they can self-check for comprehension.) As always, will be available to provide support via email, and I will be checking my inbox regularly. -

AP Music Theory Student Sample (2016) – Question 4

AP® MUSIC THEORY 2016 SCORING GUIDELINES Question 4 0–24 points I. Pitches (16 points) A. Award 1 point for each correctly notated pitch. Do not consider duration. (An accidental placed after the notehead is not considered correct notation.) B. Award full credit for octave transpositions of the correct bass pitch. (Octave transpositions of soprano pitches are not allowed.) C. No enharmonic equivalents are allowed. II. Chord Symbols (8 points) A. Award 1 point for each chord symbol correct in both Roman and Arabic numerals. B. Award ½ point for each correct Roman numeral that has incorrect or missing Arabic numerals. C. Accept the correct Roman numeral regardless of its case. (Exception: See II.E.) D. Accept any symbol that means “of” or “applied” at Chord Four (e.g., Ⅴ/iv, [Ⅴ], Ⅴ→iv, Ⅴ of iv, etc.). E. Accept a capital I for the Roman numeral of Chord Four. F. The cadential six-four may be correctly notated as shown above. Also, give full credit for the labels 6 6 “Cad 4 ” or “C 4 ” for the antepenultimate chord. If the Roman numeral of the antepenultimate chord is V, the space below the penultimate chord should contain a figure, be blank or contain a dash, or contain a V in order for the antepenultimate chord to receive any credit. However, if the space below the penultimate chord is blank, the penultimate chord will receive no credit. (8) 7 6 (5) 6 5 6 7 6 I I 6 6 6 Ⅴ Ⅴ 4 3 Ⅴ 4 Ⅴ Ⅴ Ⅴ 4 4 Ⅳ Ⅴ Ⅴ Ⅴ — Ⅴ 4 Ⅴ 4 Ex.→ 4 (3) Pts.→ 1 1 1 ½ 1 0 ½ 1 0 0 1 0 ½ ½ ½ ½ 1 ½ III. -

ANALYZING the ART SONGS of FLORENCE B. PRICE By

THE POET AND HER SONGS: ANALYZING THE ART SONGS OF FLORENCE B. PRICE by Marquese Carter Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ___________________________________________ Ayana Smith, Research Director ___________________________________________ Brian Horne, Chair ___________________________________________ Mary Ann Hart ___________________________________________ Gary Arvin November 26, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Marquese Carter iii This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my dearly departed grandmother Connie Dye and my late father Larry Carroll, Sr. I mourn that you both cannot witness this work, but rejoice that you may enjoy it from beyond a purer Veil. iv Acknowledgements I owe my gratitude to a great number of people, without whom this publication would not be possible. Firstly, I must thank the American Musicological Society for awarding me $1,200 from the Thomas Hampson Fund to support my trip to the University of Arkansas Special Collections Library. Thank you for choosing to support my early scholarly career. I must also thank the wonderful research librarians at the Special Collections for assisting me in person and through email. Without your expert guidance, Price’s unpublished works and diaries would not be available to an eager public. My sincerest gratitude to established musicologists who have strategized, encouraged, and pushed me to excel as a scholar. Chief among these is Ayana Smith, who has been an invaluable mentor since meeting at AMS Convention in 2013. -

The Death and Resurrection of Function

THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF FUNCTION A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Gabriel Miller, B.A., M.C.M., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Gregory Proctor, Advisor Dr. Graeme Boone ________________________ Dr. Lora Gingerich Dobos Advisor Graduate Program in Music Copyright by John Gabriel Miller 2008 ABSTRACT Function is one of those words that everyone understands, yet everyone understands a little differently. Although the impact and pervasiveness of function in tonal theory today is undeniable, a single, unambiguous definition of the term has yet to be agreed upon. So many theorists—Daniel Harrison, Joel Lester, Eytan Agmon, Charles Smith, William Caplin, and Gregory Proctor, to name a few—have so many different nuanced understandings of function that it is nearly impossible for conversations on the subject to be completely understood by all parties. This is because function comprises at least four distinct aspects, which, when all called by the same name, function , create ambiguity, confusion, and contradiction. Part I of the dissertation first illuminates this ambiguity in the term function by giving a historical basis for four different aspects of function, three of which are traced to Riemann, and one of which is traced all the way back to Rameau. A solution to the problem of ambiguity is then proposed: the elimination of the term function . In place of function , four new terms—behavior , kinship , province , and quality —are invoked, each uniquely corresponding to one of the four aspects of function identified. -

10Th Grade Music – Choir I: Harmonic Function May 11 – May 15 Time Allotment: 20 Minutes Per Day

10th Grade Music – Choir I: Harmonic Function May 11 – May 15 Time Allotment: 20 minutes per day Student Name: ________________________________ Teacher Name: ________________________________ Academic Honesty I certify that I completed this assignment I certify that my student completed this independently in accordance with the GHNO assignment independently in accordance with Academy Honor Code. the GHNO Academy Honor Code. Student signature: Parent signature: ___________________________ ___________________________ Music – Choir I: Harmonic Function May 11 – May 15 Packet Overview Date Objective(s) Page Number Monday, May 11 1. Review Roman numeral identification of chords 2 2. Introduce chord voicing (expanded form) Tuesday, May 12 1. Introduce harmonic function and chord 6 substitution Wednesday, May 13 1. Decode tonic/dominant relationship and define 9 goal of motion within the context of analysis Thursday, May 14 1. Discern predominant function within chorale 12 analysis Friday, May 15 1. Demonstrate understanding of harmonic function 13 by taking a written assessment. Additional Notes: In order to complete the tasks within the following packet, it would be helpful for students to have a piece of manuscript paper to write out triads; I have included a blank sheet of manuscript paper to be printed off as needed, though in the event that this is not feasible students are free to use lined paper to hand draw a music staff. I have also included answer keys to the exercises at the end of the packet. Parents, please facilitate the proper use of these answer documents (i.e. have students work through the exercises for each day before supplying the answers so that they can self-check for comprehension.) As always, will be available to provide support via email, and I will be checking my inbox regularly. -

AP Music Theory: Unit 5

AP Music Theory: Unit 5 From Simple Studies, https://simplestudies.edublogs.org & @simplestudiesinc on Instagram Harmony and Voice Leading II: Chord Progressions and Predominant Functions Harmony and Voice Leading II Predominants usually precede the dominant and are independent chords that link the harmonies between the tonic and dominant. The main examples of predominants are IV and ii. ● IV: the subdominant is used a lot by composers because it can create a smooth transition from the tonic to dominant. In the excerpt below, which is in the key of E flat Major, the bass section ascends a step, and the upper voices go from A to G. This helps steer from voice-leading issues. ○ Going from 퐼푉6to V is another pre- dominant progression. It is very useful because it creates an intensified tonal motion to the dominant. 푖푣6to V in minor form is a type of half cadence known as phrygian cadence. ● II (major), ii° (minor): The supertonic is the most common type, and it is an effective pre-dominant due to 3 reasons: ○ When the progression ii-V continues by a descending fifth (or ascending fourth) format, it is the strongest tonal root motion. ○ It introduces strong timbre and modal contrast during progressions. ○ In the image, the 2-7-1 in the soprano (ii- V-I) is a better scale degree pattern because it produces a stronger cadence in comparison to the original 1-7-1. Keep in mind.. ● The predominant model is tonic→ predominant→ dominant ● When the bass of a predominant transitions to the dominant by (4 to 5) or (6 to 5), the soprano moves in the opposite motion of the bass.