Climate Sensitive Design Principles in Municipal Processes: a Case Study of Edmonton’S Winter Patios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Jersey Symphony Orchestra Presents Beethoven's Violin Concerto with Pinchas Zukerman

New Jersey Symphony Orchestra Press Contact: Victoria McCabe, NJSO Senior Manager of Public Relations & Communications 973.735.1715 | [email protected] www.njsymphony.org/pressroom FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE New Jersey Symphony Orchestra presents Beethoven’s Violin Concerto with Pinchas Zukerman Part of the 2017 NJSO Winter Festival Zukerman—Artistic Director of three-week Winter Festival—solos in Beethoven’s sole violin concerto Concerts also feature Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3, “Organ,” Barber’s Overture to The School for Scandal Christian Vásquez conducts NJSO Accents: Organ tour and recital at Newark’s Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Classical Conversations, mentoring talkback Fri, Jan 20, at Richardson Auditorium in Princeton Sat, Jan 21, at NJPAC in Newark Sun, Jan 22, at Mayo Performing Arts Center in Morristown NEWARK, NJ (December 13, 2016)—The New Jersey Symphony Orchestra presents Beethoven’s Violin Concerto with Pinchas Zukerman, the second program of the three-weekend 2017 Winter Festival, January 20–22 in Princeton, Newark and Morristown. Christian Vásquez conducts a program that also features Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3, “Organ,” and Barber’s Overture to The School for Scandal. Performances take place on Friday, January 20, at 8 pm at the Richardson Auditorium in Princeton; Saturday, January 21, at 8 pm at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark; and Sunday, January 22, at 3 pm at the Mayo Performing Arts Center in Morristown. In a preview of the 2017 Winter Festival crafted around Zukerman, The Asbury Park Press anticipates the performances by the “violinist extraordinaire,” writing: “Zukerman is something of a legend in the classical music world, with a nearly 2017 NJSO Winter Festival: Zukerman & Beethoven’s Violin Concerto – Page 2 half-century career as soloist and conductor. -

Sámi Heritage at the Winter Festival in Jokkmokk, Sweden

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232910710 Sámi Heritage at the Winter Festival in Jokkmokk, Sweden Article in Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism · May 2006 DOI: 10.1080/15022250600560489 CITATIONS READS 44 403 2 authors, including: Robert Pettersson Mid Sweden University 24 PUBLICATIONS 605 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Robert Pettersson on 01 June 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Sámi Heritage at the Winter Festival in Jokkmokk, Sweden Dieter K. Müller a; Robert Pettersson b Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp.54-69 Abstract Indigenous tourism is an expansive sector in the growing tourism industry. However, the tourist experience of the indigenous heritage is often delimited to staged culture in museums, exhibitions and festivals. In this paper, focus is put on the annual Sámi winter festival in Jokkmokk, Sweden. It is discussed to what extent this festival truly is an indigenous event. This is accomplished by scrutinizing the Sámi representation at the festival regarding its content and its spatial location. It is argued that the available indigenous heritage is highly staged, although backstage experiences are available for the Sámi and for the curious tourists. Keywords: Cultural event; indigenous festival; Sámi tourism; Sápmi; Jokkmokk Introduction Indigenous experiences are coveted, but often hard to catch. Thanks to a growing industry of indigenous tourism the accessibility increases. According to Smith (1996) there are four different elements which are influential in the development of indigenous tourism, and can be a part of the tourist experience: habitat, history, handicrafts and heritage. -

Jauary 12, 2021 Winter Carnival Trivia Q&A Slides

About Historic Saint Paul Historic Saint Paul is a nonprofit working tostrengthen Saint Paul neighborhoods by preserving and promoting their cultural heritage and character. We have been around more than twenty years. We work in partnership with private property owners, community organizations, and public agencies to leverage Saint Paul’s cultural and historic resources as assets in economic development and community building initiatives. About Saint Paul Winter Carnival The Saint Paul Festival and Heritage Foundation’s 135th Saint Paul Winter Carnival will run for 11 days (Jan. 28 - Feb. 7), the festival will attract 250,000+ people from Saint Paul and beyond to celebrate winter in Minnesota. Landmark Center, located in the heart of downtown Saint Paul, the Minnesota State Fairgrounds, and businesses throughout the city will be venues for event festivities, which include ice carving competitions, family-friendly artistic and educational activities, and much more! Bob Olsen is the “official unofficial historian of the Saint Paul Winter Carnival Ice Palaces” and has been enamored with ice palaces since he was ten years old. In 1976, he helped revive the tradition, consulting on the first ice palace in 28 years. His work on Ice Palaces is part of the permanent collection of the Minnesota Historical Society and has been featured in a number of publications, including National Geographic and Time Magazine. Round 1 1. The very first winter carnival was inspired by what? A. A competition between Saint Paul & Minneapolis B. The 1884 Olympics C. Bad press that Minnesota was like Siberia D. Visitors & Tourism Bureau generating winter tourism 2. -

Canada's Best Winter Festivals

Category All Month All Province All Keywords Enter keywords City Enter city FIND A RACE ARTICLES Canada's Best Winter Festivals Ice canoeing, igloo building, snow slides and sleigh rides. Avoid hibernation this winter When the hot sun and warm temperatures go away, Canadians bundle up and head up to play! Instead of hibernating this winter, celebrate our snowy seasons by partaking in some of these fabulous winter festivals. Igloofest (Montreal, QC) Who says you need to wait until summer for the hottest (or coolest) music festivals? Igloofest is an outdoor concert series happening on Thursdays to Saturdays from January 14 to February 6, 2016 in Montreal’s Old Port. Don your best winter woolies and dance to the best local and international DJs amid icy décor. Winter Carnival (Quebec City, QC) Take a selfie with Canada’s iconic Bonhomme at this popular winter festival held in Quebec City from January 29 to February 14, 2016. Winter Carnival features a ton of activities for all ages, including snow bath, ice canoe race, night parades, snow slides, snow sculptures and sleigh rides. Winterlude (Ottawa–Gatineau, ON) Winterlude is the mother of all Canadian winter festivals, held at various locations around the nations capitol from January 29 to February 15, 2016. Skate on the world's largest skating rink, check out the ice sculpture competitions, play in North America's largest snow playground or even participate in a winter triathlon. Festival du Voyageur (Winnipeg, MB) Celebrate French Canadian, Métis and First Nations cultures at the Festival du Voyageur at Voyageur Park in Winnipeg, MN from February 12 to February 21, 2016. -

February – Quebec – Winter Carnival

Celebrates Canada 150 - Quebec Bienvenue au Quebec (Welcome to Quebec)! Quebec was one of the original four provinces that formed Canada in 1867. Known as “la belle province” (the beautiful province) to its locals, Quebec is the largest Canadian province (in terms of area). Quebec is a vibrant multicultural province, often recognized as the “Europe of North America”. Quebec is also famous for its vast forests, rolling hills and countless waterways. Quebec is the only province whose official language is French. The capital city is Quebec City, with a population of nearly 800,000. Quebec is also home to Canada’s second largest city, and the second largest French-speaking city in the world, Montreal (more than four million people). Continental air masses are common in Québec, the temperature is affected by marine currents. One of the most important of these is the cold Labrador Current. It moves southward from Labrador to Newfoundland. It is the main cause of cool East Coast summers and the Gulf Stream is responsible for humid heat waves during the summer. Because of the frequent meeting of warm tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico and cold, dry air from the north or west, the entire province receives heavy snowfalls during the winter. Snowy winters in Quebec don’t keep locals and visitors from having fun. The Quebec area boasts fantastic terrain and exceptional conditions, with an average natural snowfall of over 400cm each year! You can ski or snowboard at any of the four resorts just minutes from Quebec City. You can also enjoy ice-skating, dogsledding, Nordic spas, snowmobiling, snow sliding, cross country skiing, and the famous Winter Carnival! Click here to view a photo gallery of Quebec http://bit.ly/2fm5AbU Fun Facts – Quebec 1. -

Winter Must-Do's

RIDEAU CANAL SKATEWAY WINTER MUST-Do’s HERITAGE Let it snow. Ottawa is home to a flurry of winter pleasures. The city’s winter wonderland includes frosty festivals, natural wonders, icy CANADIAN : escapades, sizzling saunas, and cozy comforts. PHOTO Ice Escapades trails or cross-country ski trails stretching 200 When life gives you winter, make Winterlude! kilometres (124 miles). Looking to avoid peo- The iconic winter festival includes must- ple? Hit 50 kilometres of backcountry trails. visits like Snowflake Kingdom(slides, snow Looking for new friends or refuge? Stop at a sculptures, mazes and more) and the magi- day-use shelter equipped with wood-burning cal ice sculptures of Crystal Garden. Other stoves, picnic tables, and outhouses. Or stay in frozen bedrocks of Winterlude include an one of the four-season tents, yurts, or cabins international ice-carving competition, snow for a winter camping experience. Ottawa’s sculptures, sleigh rides, and a bed race on the Greenbelt is also home to 150 kilometres of Rideau Canal Skateway. Speaking of the cross-country ski trails. For the more adven- GATINEAU PARK world’s largest outdoor skating rink, you can turous, try ice fishing on the Ottawa River glide 7.8 kilometres (nearly 5 miles) between or dogsledding in the Outaouais Region with downtown and Dow’s Lake Pavilion, which is Escapade Eskimo. Other day trip options include Ontario’s Cala- home to several restaurants, as well as skate and bogie Peaks Resort, only 75 minutes away, sleigh rentals. The Canal isn’t the only reason Plant Your Poles with 24 downhill runs, and snowshoeing, to sharpen your blades. -

Hokkaido's Winter Festivals 2022

Hokkaido’s Winter Festivals 2022- TOUR #1 February 3rd-11th, 2022 non-stop via Cancel for any reason up to 60 days prior-FULL REFUND! Maximum Tour size is 24 tour members! 7nights/9days from: $3495 double/triple $3895 single Welcome to winter in Hokkaido. Come along, journey with us to the far north of Japan, a land of snow! For seven days, every February Sapporo is turned into a winter dreamland of crystal-like ice and white snow. The Sapporo Snow Festival, one of Japan’s largest winter events attracts nearly two million visitors who come to see the many snow and ice sculptures along Odori Park and on Susukino’s main street. They include an array of intricate ice carvings as well as massive snow sculptures that are bigger than some of the city buildings. On this Hokkaido Winter Festivals Tour #1, we welcome in the 73rd Sapporo Snow Festival, but this is only the beginning as we will be visiting a total of 6 festivals. In additional to the Sapporo Snow Festival, we have the Susukino Ice Sculptures, Lake Shikotsu Ice Festival, Sairinka Light Up, Sounkyo Ice Light Up Festival, and the Asahikawa Snow Festival. And yet there is more, much more, 3 onsen stays, a visit to the historic harbor city of Otaru, sake brewery visit, Asahikakwa Zoo to witness the Penguin Walk, Sunagawa Highway Oasis for the very best omiyage shopping under one roof, Sapporo’s Nijo Fish Market and Tanukikoji Shopping Arcade for ono shopping. If this was not enough, how about 2 nights at Sapporo’s finest hotel, Century Royal Hotel Sapporo. -

Ottawa Experiences Ottawa Best the Ottawa’S Other Bond with Nature Is Its Rivers

THE BEST OF 1 OTTAWA s a native of Ottawa, I’ve seen this city evolve over the past 5 decades from a sleepy civil-service Atown to a national capital that can proudly hold its own with any city of comparable size. The official population is more than 800,000, but the central core is compact and its skyline relatively short. Most Ottawans live in suburban, or even rural, communities. The buses are packed twice a day with government workers who live in communities like Kanata, Nepean, Gloucester, and Orleans, which were individually incorporated cities until municipal amalgamation in 2001. Although there are a number of residential neighborhoods close to downtown, you won’t find the kind of towering condominiums that line the downtown streets of Toronto or Vancouver. As a result, Ottawa is not the kind of city where the downtown side- walks are bustling with people after dark, with the excep- tion of the ByWard Market and Elgin Street. One could make the case that Ottawa would be very dull indeed were it not for Queen Victoria’s decision to anoint it capital of the newly minted Dominion of Canada. Thanks to her choice, tourists flock to the Parlia- ment Buildings, five major national museums, a handful of government- funded festivals, and the Rideau Canal. Increasingly, tourists are spreading COPYRIGHTEDout beyond the well-established attractions MATERIAL to discover the burgeoning urban neighborhoods like Wellington West and the Glebe, and venturing into the nearby countryside. For visitors, Ottawa is an ideal walking city. Most of the major attrac- tions—and since this is a national capital, there are many—are within easy walking distance of the major hotels. -

Sami Tourism in Northern Sweden

Sami Tourism in Northern Sweden Supply, Demand and Interaction Akademisk avhandling som med vederbörligt tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet för vinnande av filosofie doktorsexamen framlägges för offentlig granskning vid Kulturgeografiska institutionen, Umeå universitet torsdagen den 4 mars 2004 kl. 10.15 i BT 102, Beteendevetarhuset av Robert Pettersson Pettersson, Robert. Sami Tourism in Northern Sweden – Supply, Demand and Interaction. Doctoral dissertation in Social and Economic Geography at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Umeå University, Sweden, 2003. Abstract: Indigenous tourism is an expansive sector in the growing tourism industry. The Sami people living in Sápmi in northern Europe have started to engage in tourism, particularly in view of the rationalised and modernised methods of reindeer herding. Sami tourism offers job opportunities and enables the spreading of information. On the other hand, Sami tourism may jeopardise the indigenous culture and harm the sensitive environment in which the Sami live. The aim of this thesis is to analyse the supply and demand of Sami tourism in northern Sweden. This is presented in four articles, preceded by an introductory section describing the purpose, method, theory, background, empirical evidence, and with a discussion and summaries in English and Swedish. The first two articles describe Sami tourism from a producer (article I) and a consumer perspective (article II), respectively. The question is to what extent the supply of tourist attractions related to the Swedish Sami corresponds to the demand of the tourists. The first article analyses the potential of the emerging Sami tourism in Sweden, with special emphasis on the access to Sami tourism products. -

4.8 Human Heritage Appreciation

RECREATIONAL VALUES 206 4.8 Human Heritage Appreciation The extraordinary history and human heritage of the Ottawa River is a source of pride for numerous communities along its shores. These are reflected in the many special events, festivals, museums, Figure 4.16 Looking Up the Ottawa From plaques and other interpretive structures that the Parliament Grounds exist along the length of the river. The Ottawa River flows through the Nation’s Capital, right by the Parliament Buildings, with sites and museums of national importance. Along the entire stretch of the river there are opportunities for human heritage appreciation related to the main heritage themes of the river. This section highlights a number of popular human heritage sites, focusing on museums and events along the river. Cultural heritage tourism is growing worldwide, Source : Picturesque Canada and is seen by the Ontario Tourism Marketing Partnership Corporation as a significant opportunity for Ontario’s rural and northern communities to increase their economic vitality (Professional Edge 3). The Outaouais region is Quebec’s third most popular tourism destination, although marketing of this region places a greater emphasis on natural heritage. Ottawa draws more than 5 million visitors annually, of which currently only 20 to 25% cross the Ottawa River to visit the Canadian Museum of Civilization and Gatineau Park (Ville de Gatineau: “Planification”). 4.8.1 Cultural Heritage Routes Cultural heritage routes have been developed on both sides of the river. Thematic visits and driving loops have been developed by tourism associations such as Tourisme Outaouais and the Ottawa Valley Tourism Association. Examples of cultural heritage routes with accompanying interpretation include the following: • Ottawa River Living Legacy Kiosks: A series of 12 interpretive kiosks have been placed along the length of the Ottawa River to recognize its history and unique ecology, as part of Ontario’s Living Legacy Landmarks program. -

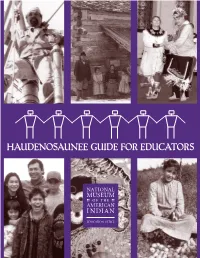

Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators

HAUDENOSAUNEE GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS EDUCATION OFFICE We gather our minds to greet and thank the enlightened Teachers who have come to help throughout the ages. When we forget how to live in harmony, they remind us of the way we were instructed to live as people. With one mind, we send greetings and thanks to these caring Teachers. Now our minds are one. From the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address Dear Educator, he Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian is pleased to bring this guide to you. It was written to help provide teachers with a better Tunderstanding of the Haudenosaunee. It was written by staff at the Museum in consultation with Haudenosaunee scholars and community members. Though much of the material contained within this guide may be familiar to you, some of it will be new. In fact, some of the information may challenge the curriculum you use when you instruct your Haudenosaunee unit. It was our hope to provide educators with a deeper and more integrated understanding of Haudenosaunee life, past and present. This guide is intended to be used as a supplement to your mandated curriculum. There are several main themes that are reinforced throughout the guide. We hope these may guide you in creating lessons and activities for your classrooms. The main themes are: Jake Swamp (Tekaroniankeken), ■ a traditional Mohawk spiritual The Haudenosaunee, like thousands of Native American nations and communities leader, and his wife Judy across the continent, have their own history and culture. (Kanerataronkwas) in their ■ The Peacemaker Story, which explains how the Confederacy came into being, is home with their grandsons the civic and social code of ethics that guides the way in which Haudenosaunee Ariwiio, Aniataratison, and people live — how they are to treat each other within their communities, how Kaienkwironkie. -

2021 Request for Artisan Ice Sculptures

2021 SAINT PAUL WINTER CARNIVAL REQUEST FOR ARTISAN ICE SCULPTURES Drive Thru Event: Jan. 28 – Feb. 7, 2021 The 2021 Saint Paul Winter Carnival will be held January 28 – February 7. This will be the festival’s 135th anniversary further fortifying the fact that it is the oldest winter festival in the United States. New this year, a Drive-Thru Ice and Snow Sculpture Park at Minnesota State Fairgrounds will create magical memories and run each day of carnival. We are excited for your role in the success of this beloved tradition with its new twist. We invite you to submit your artisan ice sculpture plan for this Drive-Thru Event by filling out the form below. Ice and snow masterpieces will be combined in this Drive-Thru Event to feature 30 different and intriguing visual aspects for attendees to view, all from the comfort of their car. Specifically, your role will be to contribute to our themed Artisan areas (Minnesota, Winter Activities, Animals, Fairy Garden or Other). Our appreciation for your hard work will not go unnoticed! Carver name and sculpture title will be listed on Saint Paul Winter Carnival mobile app and website, along with on-site signage and event program. 1. Carvers will be paid $65 per block of ice carved plus receive the following: • Power • Sweatshirt • Light snacks • Parking • Warm spot • Access to water • Clean area 2. Carving can begin Saturday, January 23rd, 2021 and must be completed by Thursday, January 28th, 2021. Carvers are welcome to carve anytime during this timeframe, please record your availability to carve below.