EH & OWH PAPERS, Series 7, Box 19, Folder 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Volume 10 No.2 September 2007 Edition No.38

The Speedway Researcher Promoting Research into the History of Speedway and Dirt Track Racing Volume 10 No.2 September 2007 Edition No.38 Cheetahs Crash It is always sad to see a track or team close down and the sudden demise of Oxford as an Elite League venture happened just as our previous edition went to copying. At the time of noting the end of the Cheetahs as an Elite League team our thoughts were the silver lining – comfort zone if you like – is that the stadium is not under threat of re-development and hopefully the City of Dreaming Spires would see speedway action soon. And so it came to pass that aspiring Exeter saviour Allen Trump has stepped into the gulf and saved the Conference League lads who now race under the name of Cheetahs. Allen has given the place a boost by hiring Peter Oakes to boot. Good luck lads – Lang May Yer Lum Reek (wi other folks’coal). JH Goodbye Michal and Kenny Whilst it is sad to lose a track, it is heartbreaking to lose riders. We send our deepest sympathies to the families of young Czech Republic rider Michal Matula and Swede Kenny Olsson who lost their lives on Sunday 27th May and Wednesday 6th June respectively. Michal never raced for a UK team but Kenny was a popular member of the Glasgow Tigers during his la st spell over here and the loss will be deeply felt by the Tigers’ fans and other admirers who followed his other teams in the UK. We will add their names to the Roll of Honour and hope, as ever, they will be the last names we will add to it. -

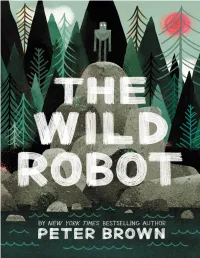

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

Tnemreie and RADIO REVIEW

TNeMreIe AND RADIO REVIEW VOLUME XXIII JULY 4th -DECEMBER 26th, 1928 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published from the Offices of " THE WIRELESS WORLD " ILIFFE & SONS LTD., DORSET HOUSE, TUDOR ST.. LONDON. E.C.4 www.americanradiohistory.com 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 11I I l l I1I111I I l 1111111111111111111111111111111111I111111 INDEX VOLUME XXIII JULY 4th -DECEMBER 26th, 1928 i l l l l l l __ 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I 1111111111111111 r A.B. Products -H.F. Choke, 774 Brayton Trickle Charger, The, 08e Current Topics, 11, 43, 69, 109, 133, 167, 195, Abroad, Programmes from, 15, 45, 78, 105, 135, Bright Emitters as Rectifiers, 183 231, 255, 287, 317, 359, 391, 472, 603, 531, 169, 197,- 227, 257, 283, 319, 365, 393, 468, British Acoustic Film System, The (Talking 561, 587, 633, 661, 701, 727, 765, 795, 818, 505, 533, 565, 601, 635, 673, 713, 733, 761, Films), 842 850 797, 820, 860 Phototone System (Talking Films), 792 " Cylanite," 688 Programmes from (Editorial), 1 -Broadcast ('yldon Synchratune -, Brevities, 23, 54, 85, 117, 143. 177, Twin Condensers, 743 -, Sets for, 808 203, 233, 268, 296, 323, 363, 445, 481, 515. Accumulator Carrier, Weston, 564 543, 573. 599, 641, 682, 711, 745, 772, 805. Charging, 489 832, 865 Damped but Distoitionless, - Discharge, 749 - Equalising, 272 Broadcasting Monopoly, The (Editorial), 155 Davex Eliminator, 19 Knobs, Clix, 112 Scientific Foundations of, 728 Tuners, 564 - or -, Eliminator? 750 Stations, 206 -" D.C.5," A Batteryless Receiver for -Accumulators, D.C. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Still on the Road Venue Index 1956 – 2016

STILL ON THE ROAD VENUE INDEX 1956 – 2016 STILL ON THE ROAD VENUE INDEX 1956-2016 2 Top Ten Concert Venues 1. Fox Warfield Theatre, San Francisco, California 28 2. The Beacon Theatre, New York City, New York 24 3. Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York 20 4. Nippon Budokan Hall, Tokyo, Japan 15 5. Hammersmith Odeon, London, England 14 Royal Albert Hall, London, England 14 Vorst Nationaal, Brussels, Belgium 14 6. Earls Court, London, England 12 Jones Beach Theater, Jones Beach State Park, Wantagh, New York 12 The Pantages Theater, Hollywood, Los Angeles, California 12 Wembley Arena, London, England 12 Top Ten Studios 1. Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York 27 2. Studio A, Power Station, New York City, New York 26 3. Rundown Studios, Santa Monica, California 25 4. Columbia Music Row Studios, Nashville, Tennessee 16 5. Studio E, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York 14 6. Cherokee Studio, Hollywood, Los Angeles, California 13 Columbia Studio A, Nashville, Tennessee 13 7. Witmark Studio, New York City, New York 12 8. Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, Sheffield, Alabama 11 Skyline Recording Studios, Topanga Park, California 11 The Studio, New Orleans, Louisiana 11 Number of different names in this index: 2222 10 February 2017 STILL ON THE ROAD VENUE INDEX 1956-2016 3 1st Bank Center, Broomfield, Colorado 2012 (2) 34490 34500 30th Street Studio, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York 1964 (1) 00775 40-acre North Forty Field, Fort Worth Stockyards, Fort Worth, Texas 2005 (1) 27470 75th Street, -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 510 27 May 2010 No. 7 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 27 May 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 283 27 MAY 2010 Business of the House 284 common sense and consideration for the House in the House of Commons Conservative-Liberal Democrat Government’s handling of the £6 billion cuts announcement and the leaking of Thursday 27 May 2010 the Queen’s Speech. The fact that we read about the contents of the Queen’s Speech in newspapers at the weekend before it The House met at half-past Ten o’clock was announced to Parliament displayed a disturbing lack of courtesy to the House. The response from PRAYERS Downing street is that although they are disappointed, there will be no leak inquiry. That demonstrates extremely poor judgment from the Government, and I ask the [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Leader of the House to explain why no investigation will be carried out. Business of the House It was also extremely disturbing that the Government chose to announce £6 billion of spending cuts while the 10.34 am House was not sitting. I am sure that you, Mr Speaker, recognised that that was not the way to treat the House Ms Rosie Winterton (Doncaster Central) (Lab): May when you granted the urgent question tabled by the I ask the Leader of the House to give us the business for Opposition yesterday. -

Courier Gazette : June 22, 1939

Issued 'IbESD/nr Thursday Saturday he ourier azette T Entered as Second ClassC Mall Matte* -G Established January, 1846. By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, June 22, 1939 TWELVE PAGES Volum e 9 4 ................... Number 74. The Courier-Gazette Clock For Copeland [EDITORIAL] THREE-TIMES-A-WEF.K i UNDER A RIVER AND OVER IT HOW FINLAND PAYS THE MAN FROM WYOMING Editor Warren Man Gets Award WM. O. PULLER In this locality where there are many Finnish people, we Associate Editor For 25 Years Of Insur With “The Sleepy City” On One Side and Wide have all felt especially proud of the good sportsmanship shown Ralph H. Smith Of Cheyenne Visiting Relatives PRANK A. WINSLOW ance Service by that Nation in the meeting of its war obligations. Possibly many have wondered how a comparatively small nation Suhecrlptlons 63 W) oer year payable Awake World’s Fair On the Other Io advance: single copies three cen ts. Sidney F Copeland, well known could do this when the wealthy powers fail to meet their just and Friends Back East Advertising rates based upon circula tion and eery reasonable insurance man of Warren, who obligations. The Herald Tribune answers the query in the NEWSPAPER HISTORY represents the Fidelity-Phenix Flrp • By The Roving Reporter—Second Installment) following editorial: A Wyoming motor car parked in When Mr. Smith falls in com The Rockland Oaaette was estab Today Finland once more hes the honor of being the only lished In 1646 In 1614 the Courier w v Insurance Company, a member front of The Courier-Gazette office pany with one of ids best Cheyenne established and consolidated with the It was the last day of school all nation to pay its war debt to the United States government in •lazette In 1862 The Free Press was company of the America Fire In along the line, and buses were scur full. -

The Kursaal Eastern Esplanade Southchurch Avenue Southend-On-Sea Ss1 2Ww

THE KURSAAL EASTERN ESPLANADE SOUTHCHURCH AVENUE SOUTHEND-ON-SEA SS1 2WW ICONIC LEISURE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY THE KURSAAL EASTERN ESPLANADE, SOUTHCHURCH AVENUE, SOUTHEND-ON-SEA SS1 2WW ICONIC LEISURE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SOUTHEND’S LONGEST PLEASURE PIER ADVENTURE SEA LIFE THE THE ROYALS SOUTHEND UNIVERSITY SOUTHEND IN THE WORLD LAND ADVENTURE KURSAAL SHOPPING CENTRE CENTRAL OF ESSEX VICTORIA P P For indicative purposes only. THE KURSAAL EASTERN ESPLANADE, SOUTHCHURCH AVENUE, SOUTHEND-ON-SEA SS1 2WW ICONIC LEISURE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS ■ Prominent landmark listed building on Southend’s main leisure pitch ■ Total rent of £814,415 pa equating to a low rent of £7.29 psf ■ The property is centrally located, approximately 1 mile from both Southend Central ■ Over 10 years WAULT and Southend East train stations ■ Asset Management opportunities to include letting vacant first floor ■ Southend is an affluent commuter town with excellent links to London Liverpool ■ We are instructed to seek offers in excess of £8,000,000 (Eight Million Street and London Fenchurch Street Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level ■ 146 car park spaces to the rear reflects a Net Initial Yield of 10.00%, allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.67%. ■ Building totals 10,948.8 sq m (117,853 sq ft) This represents a low capital rate of £67.88 psf. THE KURSAAL EASTERN ESPLANADE, SOUTHCHURCH AVENUE, SOUTHEND-ON-SEA SS1 2WW ICONIC LEISURE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY LOCATION The popular seaside town of Southend-on-Sea is situated within the County of Essex located approximately 39 miles (62 km) east of London, 19 miles (30 km)A5 south A505 Stevenage of Chelmsford and 20 miles (32 A418km) east of Brentwood.Dunstable Stansted Colchester A5 Luton Luton Bishop’s A120 Braintree Road access to Southend is provided by the A127 dual Knebworth A10 Stortford carriageway which in turn, providesA418 access to Junction 29 of A602 A5 A131 the M25, approximatelyAylesbury 20 miles (32 km) to the west. -

Braintree Area Profile 2003

Learning and Skills Council, Essex Braintree Area Profile BRAINTREE Foreword.........................................................................................iv Understanding the data..................................................................v Enquiries and Further Copies.......................................................vi Key Statistics...................................................................................1 PEOPLE...................................................................................................2 1. Population....................................................................................2 1.1 Age.........................................................................................................3 1.2 Gender....................................................................................................6 1.3 Ethnicity.................................................................................................7 1.4 Disability................................................................................................8 2. The Labour Force......................................................................10 2.1 Unemployment....................................................................................13 2.2 Employment.........................................................................................16 2.2.1 The Braintree Based Workforce............................................................16 2.2.2 Travel to Work Patterns..........................................................................23 -

SOUTHEND UNITED FAN GUIDE a Warm Welcome

SOUTHEND UNITED FAN GUIDE A warm welcome... A warm welcome to Roots Hall; the home of Southend United Football Club. Whether it’s your first or 1,000th time we want to make your experience of visiting Roots Hall as good as possible. We have compiled this guide to make it easier every step of the way. Naturally, the main focal point of your day will focus around the football. As you will see from this guide there is plenty more to enjoy in the Southend on Sea area. This guide shows you the best way to secure your tickets, how to travel to Roots Hall, what food and drink is on offer, what items to purchase in the Club Shop & much more! We make no secret that Roots Hall is one of football’s historic grounds, we have recently submitted plans for an exciting redevelopment at nearby Fossett’s Farm - keep an eye on our official website for more details. If there is anything else we have missed please do not hesitate to contact us: [email protected] 08444 770077 SOUTHEND UNITED FAN GUIDE How to purchase tickets from Roots Hall... The best way to support the Blues is with a season card! Join over 3,850 season card holders at every home Sky Bet League One fixture and priority access to cup and away games plus an array of additional benefits. We have made purchasing tickets for Southend United games even easier with our Print @ Home tickets - you can now purchase right up until the start of the game and print from home. -

HERITAGE at RISK REGISTER 2009 / EAST of ENGLAND Contents

HERITAGE AT RISK REGISTER 2009 / EAST OF ENGLAND Contents HERITAGEContents AT RISK 2 Buildings atHERITAGE Risk AT RISK 6 2 MonumentsBuildings at Risk at Risk 8 6 Parks and GardensMonuments at Risk at Risk 10 8 Battlefields Parksat Risk and Gardens at Risk 12 11 ShipwrecksBattlefields at Risk and Shipwrecks at Risk13 12 ConservationConservation Areas at Risk Areas at Risk 14 14 The 2009 ConservationThe 2009 CAARs Areas Survey Survey 16 16 Reducing thePublications risks and guidance 18 20 PublicationsTHE and REGISTERguidance 2008 20 21 The register – content and 22 THE REGISTERassessment 2009 criteria 21 Contents Key to the entries 21 25 The registerHeritage – content at Riskand listings 22 26 assessment criteria Key to the entries 24 Heritage at Risk entries 26 HERITAGE AT RISK 2009 / EAST OF ENGLAND HERITAGE AT RISK IN THE EAST OF ENGLAND Registered Battlefields at Risk Listed Buildings at Risk Scheduled Monuments at Risk Registered Parks and Gardens at Risk Protected Wrecks at Risk Local Planning Authority 2 HERITAGE AT RISK 2009 / EAST OF ENGLAND We are all justly proud of England’s historic buildings, monuments, parks, gardens and designed landscapes, battlefields and shipwrecks. But too many of them are suffering from neglect, decay and pressure from development. Heritage at Risk is a national project to identify these endangered places and then help secure their future. In 2008 English Heritage published its first register of Heritage at Risk – a region-by-region list of all the Grade I and II* listed buildings (and Grade II listed buildings in London), structural scheduled monuments, registered battlefields and protected wreck sites in England known to be ‘at risk’.