Hertz' Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Hertz Astrophysics Subcommittee

Paul Hertz Astrophysics Subcommittee February 23, 2012 Agenda • Science Highlights • Organizational Changes • Program Update • President’s FY13 Budget Request • Addressing Decadal Survey Priorities 2 Chandra Finds Milky Way’s Black Hole Grazing on Asteroids • The giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way may be vaporizing and devouring asteroids, which could explain the frequent flares observed, according to astronomers using data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory. For several years Chandra has detected X-ray flares about once a day from the supermassive black hole known as Sagittarius A*, or "Sgr A*" for short. The flares last a few hours with brightness ranging from a few times to nearly one hundred times that of the black hole's regular output. The flares also have been seen in infrared data from ESO's Very Large Telescope in Chile. • Scientists suggest there is a cloud around Sgr A* containing trillions of asteroids and comets, stripped from their parent stars. Asteroids passing within about 100 million miles of the black hole, roughly the distance between the Earth and the sun, would be torn into pieces by the tidal forces from the black hole. • These fragments then would be vaporized by friction as they pass through the hot, thin gas flowing onto Sgr A*, similar to a meteor heating up and glowing as it falls through Earth's atmosphere. A flare is produced and the remains of the asteroid are eventually swallowed by the black hole. • The authors estimate that it would take asteroids larger than about six miles in radius to generate the flares observed by Chandra. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Electric and Magnetic Fields the Facts

PRODUCED BY ENERGY NETWORKS ASSOCIATION - JANUARY 2012 electric and magnetic fields the facts Electricity plays a central role in the quality of life we now enjoy. In particular, many of the dramatic improvements in health and well-being that we benefit from today could not have happened without a reliable and affordable electricity supply. Electric and magnetic fields (EMFs) are present wherever electricity is used, in the home or from the equipment that makes up the UK electricity system. But could electricity be bad for our health? Do these fields cause cancer or any other disease? These are important and serious questions which have been investigated in depth during the past three decades. Over £300 million has been spent investigating this issue around the world. Research still continues to seek greater clarity; however, the balance of scientific evidence to date suggests that EMFs do not cause disease. This guide, produced by the UK electricity industry, summarises the background to the EMF issue, explains the research undertaken with regard to health and discusses the conclusion reached. Electric and Magnetic Fields Electric and magnetic fields (EMFs) are produced both naturally and as a result of human activity. The earth has both a magnetic field (produced by currents deep inside the molten core of the planet) and an electric field (produced by electrical activity in the atmosphere, such as thunderstorms). Wherever electricity is used there will also be electric and magnetic fields. Electric and magnetic fields This is inherent in the laws of physics - we can modify the fields to some are inherent in the laws of extent, but if we are going to use electricity, then EMFs are inevitable. -

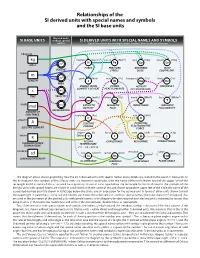

Relationships of the SI Derived Units with Special Names and Symbols and the SI Base Units

Relationships of the SI derived units with special names and symbols and the SI base units Derived units SI BASE UNITS without special SI DERIVED UNITS WITH SPECIAL NAMES AND SYMBOLS names Solid lines indicate multiplication, broken lines indicate division kilogram kg newton (kg·m/s2) pascal (N/m2) gray (J/kg) sievert (J/kg) 3 N Pa Gy Sv MASS m FORCE PRESSURE, ABSORBED DOSE VOLUME STRESS DOSE EQUIVALENT meter m 2 m joule (N·m) watt (J/s) becquerel (1/s) hertz (1/s) LENGTH J W Bq Hz AREA ENERGY, WORK, POWER, ACTIVITY FREQUENCY second QUANTITY OF HEAT HEAT FLOW RATE (OF A RADIONUCLIDE) s m/s TIME VELOCITY katal (mol/s) weber (V·s) henry (Wb/A) tesla (Wb/m2) kat Wb H T 2 mole m/s CATALYTIC MAGNETIC INDUCTANCE MAGNETIC mol ACTIVITY FLUX FLUX DENSITY ACCELERATION AMOUNT OF SUBSTANCE coulomb (A·s) volt (W/A) C V ampere A ELECTRIC POTENTIAL, CHARGE ELECTROMOTIVE ELECTRIC CURRENT FORCE degree (K) farad (C/V) ohm (V/A) siemens (1/W) kelvin Celsius °C F W S K CELSIUS CAPACITANCE RESISTANCE CONDUCTANCE THERMODYNAMIC TEMPERATURE TEMPERATURE t/°C = T /K – 273.15 candela 2 steradian radian cd lux (lm/m ) lumen (cd·sr) 2 2 (m/m = 1) lx lm sr (m /m = 1) rad LUMINOUS INTENSITY ILLUMINANCE LUMINOUS SOLID ANGLE PLANE ANGLE FLUX The diagram above shows graphically how the 22 SI derived units with special names and symbols are related to the seven SI base units. In the first column, the symbols of the SI base units are shown in rectangles, with the name of the unit shown toward the upper left of the rectangle and the name of the associated base quantity shown in italic type below the rectangle. -

Evaluating Temperature Regulation by Field-Active Ectotherms: the Fallacy of the Inappropriate Question

Vol. 142, No. 5 The American Naturalist November 1993 EVALUATING TEMPERATURE REGULATION BY FIELD-ACTIVE ECTOTHERMS: THE FALLACY OF THE INAPPROPRIATE QUESTION *Department of Biological Sciences, Barnard College, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027; $Department of Zoology NJ-15, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195; $Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts at Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02125 Submitted March 16, 1992; Revised November 9, 1992; Accepted November 20, 1992 Abstract.-We describe a research protocol for evaluating temperature regulation from data on small field-active ectothermic animals, especially lizards. The protocol requires data on body temperatures (T,) of field-active ectotherms, on available operative temperatures (T,, "null temperatures" for nonregulating animals), and on the thermoregulatory set-point range (pre- ferred body temperatures, T,,,). These data are used to estimate several quantitative indexes that collectively summarize temperature regulation: the "precision" of body temperature (vari- ance in T,, or an equivalent metric), the "accuracy" of body temperature relative to the set-point range (the average difference between 7, and T,,,), and the "effectiveness" of thermoregulation (the extent to which body temperatures are closer on the average to the set-point range than are operative temperatures). If additional data on the thermal dependence of performance are available, the impact of thermoregulation on performance (the extent to which performance is enhanced relative to that of nonregulating animals) can also be estimated. A sample analysis of the thermal biology of three Anolis lizards in Puerto Rico demonstrates the utility of the new protocol and its superiority to previous methods of evaluating temperature regulation. We also discuss several ways in which the research protocol can be extended and applied to other organisms. -

The International System of Units (SI)

NAT'L INST. OF STAND & TECH NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology Technology Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce NIST Special Publication 330 2001 Edition The International System of Units (SI) 4. Barry N. Taylor, Editor r A o o L57 330 2oOI rhe National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303. -

Aircraft Noise (Excerpt from the Oakland International Airport Master Plan Update – 2006)

Aircraft Noise (Excerpt from the Oakland International Airport Master Plan Update – 2006) Background This report presents background information on the characteristics of noise. Noise analyses involve the use of technical terms that are used to describe aviation noise. This section provides an overview of the metrics and methodologies used to assess the effects of noise. Characteristics of Sound Sound Level and Frequency — Sound can be technically described in terms of the sound pressure (amplitude) and frequency (similar to pitch). Sound pressure is a direct measure of the magnitude of a sound without consideration for other factors that may influence its perception. The range of sound pressures that occur in the environment is so large that it is convenient to express these pressures as sound pressure levels on a logarithmic scale that compresses the wide range of sound pressures to a more usable range of numbers. The standard unit of measurement of sound is the Decibel (dB) that describes the pressure of a sound relative to a reference pressure. The frequency (pitch) of a sound is expressed as Hertz (Hz) or cycles per second. The normal audible frequency for young adults is 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. Community noise, including aircraft and motor vehicles, typically ranges between 50 Hz and 5,000 Hz. The human ear is not equally sensitive to all frequencies, with some frequencies judged to be louder for a given signal than others. See Figure 6.2. As a result of this, various methods of frequency weighting have been developed. The most common weighting is the A-weighted noise curve (dBA). -

1.4.3 SI Derived Units with Special Names and Symbols

1.4.3 SI derived units with special names and symbols Physical quantity Name of Symbol for Expression in terms SI unit SI unit of SI base units frequency1 hertz Hz s-1 force newton N m kg s-2 pressure, stress pascal Pa N m-2 = m-1 kg s-2 energy, work, heat joule J N m = m2 kg s-2 power, radiant flux watt W J s-1 = m2 kg s-3 electric charge coulomb C A s electric potential, volt V J C-1 = m2 kg s-3 A-1 electromotive force electric resistance ohm Ω V A-1 = m2 kg s-3 A-2 electric conductance siemens S Ω-1 = m-2 kg-1 s3 A2 electric capacitance farad F C V-1 = m-2 kg-1 s4 A2 magnetic flux density tesla T V s m-2 = kg s-2 A-1 magnetic flux weber Wb V s = m2 kg s-2 A-1 inductance henry H V A-1 s = m2 kg s-2 A-2 Celsius temperature2 degree Celsius °C K luminous flux lumen lm cd sr illuminance lux lx cd sr m-2 (1) For radial (angular) frequency and for angular velocity the unit rad s-1, or simply s-1, should be used, and this may not be simplified to Hz. The unit Hz should be used only for frequency in the sense of cycles per second. (2) The Celsius temperature θ is defined by the equation θ/°C = T/K - 273.15 The SI unit of Celsius temperature is the degree Celsius, °C, which is equal to the Kelvin, K. -

Franck-Hertz Experiment

Franck-Hertz Experiment 1 Introduction Planck (1900) put forward the idea of quantization while solving a long standing problem of the black body radiation. He proposed that the exchange of the energy between the radiation and the matter is discrete rather than continuous. This hypothesis fueled to look for a modification in the understandings of classical physics which only deals with the continuous exchange of energy. In 1905, Einstein solved the photoelectric effect problem assuming the quantization of the light. Inspired from the success of Planck’s hypothesis and Einstein’s theory, Bohr proposed the quantization theory in describing the spectrum of hydrogen atom. According to Bohr’s assumptions, the electron in an atom revolves around the nucleus in a circular orbit under the influence of the electrostatic attraction of the nucleus placed at the centre of the orbit. Also, the electron is allowed to move in a certain set of orbits called as stationary states with discrete energy values. While moving in these orbits the electron does not radiate its energy. In these orbits the angular momentum of the electron is quantized and can take values equal to the integral multiple of h/2π, where h is the Planck constant. Each of such states of atom having a fixed energy value are called as atomic energy level. The transitions from one energy level to another can happen only if a photon of the energy equal to the difference of energies between the two energy levels is absorbed or emitted. For instance a transition between two discrete atomic energy levels Ea and Eb is associated with emission or absorption of a photon of frequency ν=(Ea- Eb)/h. -

Laser Definitions

Laser Definitions Ablation: Removal of a segment of tissue using thermal energy; also termed vaporization or thermal decomposition. Absorption: The transfer of radiant energy into the target tissue resulting in a change in that tissue. Active Medium: Any material within the optical cavity of a laser that, when energized, emits photons (radiant energy). Attenuation: The decline in the energy or power as a beam passes through an absorbing or scattering medium. Average Power: An expression of the average power emission over time expressed in Watts; total amount of laser energy delivered divided by the duration of the laser exposure. For a pulsed laser, the product of the energy per pulse (Joule) and the pulse frequency (Hertz). Beam: Radiant electromagnetic rays that may be divergent, convergent, or collimated (parallel). Chopped Pulse: See Grated Pulse Mode. Chromophore: A substance or molecule exhibiting selective light-absorbing qualities, often to specific wavelengths. Class IV Laser: A surgical laser that requires safety personnel to monitor the nominal hazard zone, eye protection, and training. This class of laser poses significant risk of damage to eyes, any nontarget tissue, and can produce plume hazards. Coagulation: An observed denaturation of soft tissue proteins that occurs at 60˚C. Contact Mode: The direct touching/contact of the laser delivery system to the target tissue. Continuous Mode: A manner of applying the laser energy in an uninterrupted (non- pulsed) fashion, in which beam power density remains constant over time; also termed continuous wave, and abbreviated as ‘CW’. Contrast with ‘Pulsed Mode’. Energy: The ability to perform work, expressed in Joules. -

Basic Audio Terminology

Audio Terminology Basics © 2012 Bosch Security Systems Table of Contents Introduction 3 A-I 5 J-R 10 S-Z 13 Wrap-up 15 © 2012 Bosch Security Systems 2 Introduction Audio Terminology Are you getting ready to buy a new amp? Is your band booking some bigger venues and in need of new loudspeakers? Are you just starting out and have no idea what equipment you need? As you look up equipment details, a lot of the terminology can be pretty confusing. What do all those specs mean? What’s a compression driver? Is it different from a loudspeaker? Why is a 4 watt amp cheaper than an 8 watt amp? What’s a balanced interface, and why does it matter? We’re Here to Help When you’re searching for the right audio equipment, you don’t need to know everything about audio engineering. You just need to understand the terms that matter to you. This quick-reference guide explains some basic audio terms and why they matter. © 2012 Bosch Security Systems 3 What makes EV the expert? Experience. Dedication. Passion. Electro-Voice has been in the audio equipment business since 1930. Recognized the world over as a leader in audio technology, EV is ubiquitous in performing arts centers, sports facilities, houses of worship, cinemas, dance clubs, transportation centers, theaters, and, of course, live music. EV’s reputation for providing superior audio products and dedication to innovation continues today. Whether EV microphones, loudspeaker systems, amplifiers, signal processors, the EV solution is always a step up in performance and reliability. -

Hearing Tests

In partnership with Primary Children’s Hospital Hearing Tests This handout explains how we measure sound, what sounds people normally hear, and how your child’s hearing is tested. It also explains hearing loss and what you can do if your child has hearing loss. What are the parts of sound? Every sound has two parts: frequency (also called pitch) and intensity (or loudness). Frequency is how high or low a sound is. A bass drum, thunder, and a man’s deep voice are low- frequency sounds. A high-pitched whistle, squeal, and a child’s voice are high-frequency sounds. Intensity is how loud or soft a sound is. If a sound is loud, it has a high intensity. If a sound is soft, it has a low intensity. How are sounds measured? Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) [hurts]. A low- frequency sound is about 500 Hz or lower. A high- frequency sound is about 2,000 Hz and higher. Behavioral testing Intensity is measured in decibels (dB) [DES-uh-buls]. A Children and sometimes even babies can have their high-intensity (loud) sound has a high decibel level. A hearing tested in a sound booth with headphones low-intensity (soft) sound has a low decibel level. The or earbuds. During a behavioral hearing test, an sound of people talking is usually between 40 and 60 dB. audiologist (a healthcare professional who tests Sounds that are louder than 90 dB are uncomfortable hearing and helps people with hearing loss) checks to and sounds louder than 110 dB can be painful.