Labor Relations in Basketball: the Lockout of 1998-99

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N.B.A. Commissioner Adam Silver: Allow Gambling on Pro Games - Nytimes.Com 11/14/14 4:12 PM

N.B.A. Commissioner Adam Silver: Allow Gambling on Pro Games - NYTimes.com 11/14/14 4:12 PM http://nyti.ms/1urf75N THE OPINION PAGES | OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR | NYT NOW Legalize and Regulate Sports Betting N.B.A. Commissioner Adam Silver: Allow Gambling on Pro Games By ADAM SILVER NOV. 13, 2014 BETTING on professional sports is currently illegal in most of the United States outside of Nevada. I believe we need a different approach. For more than two decades, the National Basketball Association has opposed the expansion of legal sports betting, as have the other major professional sports leagues in the United States. In 1992, the leagues supported the passage by Congress of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, or Paspa, which generally prohibits states from authorizing sports betting. But despite legal restrictions, sports betting is widespread. It is a thriving underground business that operates free from regulation or oversight. Because there are few legal options available, those who wish to bet resort to illicit bookmaking operations and shady offshore websites. There is no solid data on the volume of illegal sports betting activity in the United States, but some estimate that nearly $400 billion is illegally wagered on sports each year. Times have changed since Paspa was enacted. Gambling has increasingly become a popular and accepted form of entertainment in the United States. Most states offer lotteries. Over half of them have legal casinos. Three have approved some form of Internet gambling, with others poised to follow. There is an obvious appetite among sports fans for a safe and legal way to wager on professional sporting events. -

Sports Marketing, Consumer Behavior Focus on the NBA

Sports Marketing, Consumer Behavior focus on the NBA Colegio Universitario de Estudios Financieros Grado en Administración y Dirección de Empresas Bilingüe Trabajo de Fin de Grado SPORTS MARKETING, CONSUMER BEHAVIOR FOCUS ON THE Author: MacDonald del Casar, William Tutor: Fernández Moya, María Eugenia Madrid 2020 NBA Consumer Behavior Marketing 1 Sports Marketing, Consumer Behavior focus on the NBA INDEX . 1. Introduction . 2. Introduction to sports marketing o 2.1 Sports marketing o 2.2 Emergence of sports marketing . 3. Introduction to the National Basketball Association o 3.1 Creation of the league o 3.2 NBA history till this day o 3.3 NBA as a business model . 4. Consumer Behavior concepts o 4.1 Self-Concept, sports, and sporting events o 4.2 Identification and Internalization o 4.3 Sports and self-esteem o 4.4 Sports Consumption o 4.5 The role of sports in event marketing and promotion o 4.6 Approach-avoidance o 4.7 Servicescape o 4.8 Atmospheric music o 4.9 Hedonic consumption o 4.10 Structural Constrains relation to attendance o 4.11 Reference groups . 5. Advertising Marketing o 5.1 Advertising Schemas . 6. Coronavirus and the NBA . 7. Conclusion . 8. Bibliography 2 Sports Marketing, Consumer Behavior focus on the NBA 1. INTRODUCTION This project about sports and specifically about the National Basketball Association will reflect the importance and applications of the Consumer Behavior studies and theory to give not only meaning to what the NBA´s marketing strategy is, but also the relative importance of the main factors to the success of the league both on a fan level and on the revenue stream side. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball

Set Info - Player - National Treasures Basketball Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos + Cards Base Autos Memorabilia Memorabilia Luka Doncic 1112 0 145 630 337 Joe Dumars 1101 0 460 441 200 Grant Hill 1030 0 560 220 250 Nikola Jokic 998 154 420 236 188 Elie Okobo 982 0 140 630 212 Karl-Anthony Towns 980 154 0 752 74 Marvin Bagley III 977 0 10 630 337 Kevin Knox 977 0 10 630 337 Deandre Ayton 977 0 10 630 337 Trae Young 977 0 10 630 337 Collin Sexton 967 0 0 630 337 Anthony Davis 892 154 112 626 0 Damian Lillard 885 154 186 471 74 Dominique Wilkins 856 0 230 550 76 Jaren Jackson Jr. 847 0 5 630 212 Toni Kukoc 847 0 420 235 192 Kyrie Irving 846 154 146 472 74 Jalen Brunson 842 0 0 630 212 Landry Shamet 842 0 0 630 212 Shai Gilgeous- 842 0 0 630 212 Alexander Mikal Bridges 842 0 0 630 212 Wendell Carter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Hamidou Diallo 842 0 0 630 212 Kevin Huerter 842 0 0 630 212 Omari Spellman 842 0 0 630 212 Donte DiVincenzo 842 0 0 630 212 Lonnie Walker IV 842 0 0 630 212 Josh Okogie 842 0 0 630 212 Mo Bamba 842 0 0 630 212 Chandler Hutchison 842 0 0 630 212 Jerome Robinson 842 0 0 630 212 Michael Porter Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Troy Brown Jr. 842 0 0 630 212 Joel Embiid 826 154 0 596 76 Grayson Allen 826 0 0 614 212 LaMarcus Aldridge 825 154 0 471 200 LeBron James 816 154 0 662 0 Andrew Wiggins 795 154 140 376 125 Giannis 789 154 90 472 73 Antetokounmpo Kevin Durant 784 154 122 478 30 Ben Simmons 781 154 0 627 0 Jason Kidd 776 0 370 330 76 Robert Parish 767 0 140 552 75 Player Total # Total # Total # Total # Total # Autos -

2000 NBA ALL-STAR TECHNOLOGY SUMMIT the Future of Sports Programming the Ritz-Carlton, San Francisco

2000 NBA ALL-STAR TECHNOLOGY SUMMIT The Future of Sports Programming The Ritz-Carlton, San Francisco FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 11 8:15 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Continental Breakfast – The Ritz Carlton Ballroom 9:00 a.m. – 9:15 a.m. Welcome Ahmad Rashad, Summit Host Opening Comments David Stern, NBA Commissioner 9:15 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Panel I: Brand, Content and Community Moderator: Tim Russert (Moderator, Anchor, NBC News) Panelists Leonard Armato (Chairman & CEO, Management Plus Enterprises/DUNK.net) Geraldine Laybourne (Chairman, CEO & Founder, Oxygen Media) Rebecca Lobo (Center/Forward, New York Liberty) Kevin O’Malley (Senior Vice President, Programming, Turner Sports) Al Ramadan (CEO, Quokka Sports) Isiah Thomas (Chairman & CEO, CBA) Description Building a successful brand is at the core of establishing a community of loyal consumers. What types of companies and brands are best positioned for long-term success on the Net? Do new Internet-specific brands have an advantage over established off-line brands staking their claims in cyberspace? Or does the proliferation of Web-specific properties give an edge to established brands that the consumer knows, understands and is comfortable with? Panelists debate the value of an off-line brand in building traffic and equity on-line. 10:15 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. Break 10:30 a.m – 11:30 a.m Panel II: The Viewer Experience: 2002, 2005 and Beyond Moderator: Bob Costas (Broadcaster, NBC Sports) Panelists George Blumenthal (Chairman, NTL) Dick Ebersol (Chairman, NBC Sports and Olympics) David Hill (Chairman & CEO, FOX Sports Television Group) Mark Lazarus (President, Turner Sports) Geoff Reiss (SVP of Production & Programming, ESPN Internet Ventures) Bill Squadron (CEO, Sportvision) Description Analysts predict that sports and entertainment programming will benefit most from the advent of large pipe broadband distribution. -

2008 History.Indd

SPARTAN BASKETBALL HISTORY AND TRADITION 1979 NCAA CHAMPIONS The 1978-79 season was truly a magical one for Coach Jud Heathcote and his Michigan State Spartans. Blending a perfect combination of individual ability, enthu- siasm and teamwork, Heathcote formed a cohesive unit that captivated the nation and sellout crowds at Jenison Field House. The Spartans compiled a 26-6 overall record and went 13-5 in the Big Ten to share the league crown with Purdue and Iowa. State steamrolled through the NCAA Tournament, ending the season on top of the college basketball world with a 75-64 victory over Larry Bird and unbeaten Indi- ana State. The 1978-79 squad gathered at Jenison Field House on Aug. 12, 1989, to play one more game against a team of former Spartan All-Stars. On a hot, sweltering night, the National Champi- onship squad, led by Earvin Johnson’s 25 points and 17 rebounds, topped the All-Stars, 95-93, before a sellout crowd of 10,004. 126 MICHIGAN STATE MEN’S BASKETBALL 2000 NCAA CHAMPIONS Tom Izzo repeatedly talked to his team about leaving its mark on the program. The 1999-2000 Spartans did more than leave their mark; they set the standard by which all future Michigan State teams would be measured. Part of being a champion is winning titles, which the Spartans accomplished in winning the Na- tional Championship, a third straight Big Ten Championship and a second consecutive Big Ten Tourna- ment title. Michigan State’s three consecutive conference crowns marked only the eighth time in league history that a team has won three straight titles. -

Hawks' Trio Headlines Reserves for 2015 Nba All

HAWKS’ TRIO HEADLINES RESERVES FOR 2015 NBA ALL-STAR GAME -- Duncan Earns 15 th Selection, Tied for Third Most in All-Star History -- NEW YORK, Jan. 29, 2015 – Three members of the Eastern Conference-leading Atlanta Hawks -- Al Horford , Paul Millsap and Jeff Teague -- headline the list of 14 players selected by the coaches as reserves for the 2015 NBA All-Star Game, the NBA announced today. Klay Thompson of the Golden State Warriors earned his first All-Star selection, joining teammate and starter Stephen Curry to give the Western Conference-leading Warriors two All-Stars for the first time since Chris Mullin and Tim Hardaway in 1993. The 64 th NBA All-Star Game will tip off Sunday, Feb. 15, at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The game will be seen by fans in 215 countries and territories and will be heard in 47 languages. TNT will televise the All-Star Game for the 13th consecutive year, marking Turner Sports' 30 th year of NBA All- Star coverage. The Hawks’ trio is joined in the East by Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh of the Miami Heat, the Chicago Bulls’ Jimmy Butler and the Cleveland Cavaliers’ Kyrie Irving . This is the 11 th consecutive All-Star selection for Wade and the 10 th straight nod for Bosh, who becomes only the third player in NBA history to earn five trips to the All-Star Game with two different teams (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Kevin Garnett). Butler, who leads the NBA in minutes (39.5 per game) and has raised his scoring average from 13.1 points in 2013-14 to 20.1 points this season, makes his first All-Star appearance. -

National Basketball Association

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION {Appendix 2, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of July 17, 2012 Team: Atlanta Hawks Principal Owner: Atlanta Spirit, LLC Year Established: 1949 as the Tri-City Blackhawks, moved to Milwaukee and shortened the name to become the Milwaukee Hawks in 1951, moved to St. Louis to become the St. Louis Hawks in 1955, moved to Atlanta to become the Atlanta Hawks in 1968. Team Website Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $250 (2004) included Atlanta Hawks, Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and operating rights in Philips Arena. Current Value ($/Mil): $270 Percent Change From Last Year: -8% Arena: Philips Arena Date Built: 1999 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $213.5 Percentage of Arena Publicly Financed: 91% Facility Financing: The facility was financed through $130.75 million in government-backed bonds to be paid back at $12.5 million a year for 30 years. A 3% car rental tax was created to pay for $62 million of the public infrastructure costs and Time Warner contributed $20 million for the remaining infrastructure costs. Facility Website UPDATE: W/C Holdings put forth a bid on May 20, 2011 for $500 million to purchase the Atlanta Hawks, the Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and ownership rights to Philips Arena. However, the Atlanta Spirit elected to sell the Thrashers to True North Sports Entertainment on May 31, 2011 for $170 million, including a $60 million in relocation fee, $20 million of which was kept by the Spirit. True North Sports Entertainment relocated the Thrashers to Winnipeg, Manitoba. As of July 2012, it does not appear that the move affected the Philips Arena naming rights deal, © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 which stipulates Philips Electronics may walk away from the 20-year deal if either the Thrashers or the Hawks leave. -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Kevin Willis: Mr

Kevin Willis: Mr. Big & Tall - Fortune Management Page 1 of 4 Home Video Business News Markets Term Sheet Economy Tech Personal Finance Small Business Ask Annie Leadership, by Geoff Colvin Postcards You Can't Fire Everyone Business School Careers Strategy Kevin Willis: Mr. Big & Tall October 31, 2011: 5:00 AM ET 0 comments The former NBA star hopes to enter fashion's (really) big leagues. By Daniel Roberts , reporter FORTUNE -- What do most professional basketball players do after retiring? "A lot of guys get on the golf course," says Kevin Willis, whose 23 years in the NBA included a 2003 championship with the San Antonio Spurs. "A lot try to get into some type of business venture, but when you don't really have the experience, or you're not knowledgeable, it doesn't go well." That's an understatement. (Ask Scottie Pippen or Latrell Sprewell, both of whom blew their basketball bucks post- retirement.) Yet Willis, 49, a still-muscular 7-footer, made the transition so smoothly it was almost as though the NBA was merely a long, lucrative interlude in the life of his business. In a way, it was. He'd known since 1988, when Have you been given the Type your comment here. e he and Michigan State classmate Ralph Walker opened a their first Willis & Walker big and tall clothing store in handled it? interesting and instructional ones. Atlanta, that he would focus on fashion once he left basketball. Willis built the business even as he prospered in the league, playing an amazing 21 seasons before leaving at 45, in 2007. -

Showing Dirk's Value

FEBRUARY 10, 2017 7 $0.25B BARGAIN Dirk Nowitzki is not only an all-time great, his salary has also been an incredible value. BY EVAN HOOPFER l [email protected] l 214-706-7123 l @DBJHoopfer 29,797 irk Nowitzki has made nearly $242 million — or about a quarter of $1 POINTS 7th all-time billion — in his 19-year career for the Dallas Mavericks.While that’s a 10,681 lot of money for playing basketball, he has actually been underpaid REBOUNDS relative to his performance. Nowitzki is one of the all-time greats. 33rd all-time DHow great? Tere’s a statistic that quantifies NBA players’ overall performance 21.8 called “win shares.” For example, in Nowitzki’s 2006-07 season when he won CAREER PPG MVP, he had 17.7 win shares. Tat means if you took Nowitzki off the Mavericks 87.9% that season, the team would win 17.7 less games. FREE THROW % He has never been the highest-paid player in the NBA, but during his career, 38.1% he’s had more win shares in a season than the highest-paid player in the league 3-POINT % 13 times. He has taken a smaller salary in the past to help the team with the salary R 13-time All-Star cap, but this year Nowitzki is making a career-high $25 million. Te negotiations R ‘06-07 NBA MVP between Nowitzki and Mavericks owner Mark Cuban weren’t typical. Nowitzki R ‘10-11 NBA champ /Finals MVP asked for a number, but the team had more money to play with so they gave him AS OF FEB. -

Rockets in the Playoffs

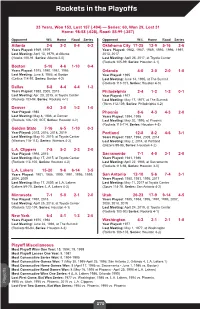

Rockets in the Playoffs 33 Years, Won 153, Lost 157 (.494) — Series: 60, Won 29, Lost 31 Home: 98-58 (.628), Road: 55-99 (.357) Opponent W-L Home Road Series Opponent W-L Home Road Series Atlanta 2-6 2-2 0-4 0-2 Oklahoma City 17-25 12-9 5-16 2-6 Years Played: 1969, 1979 Years Played: 1982, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997, Last Meeting: April 13, 1979, at Atlanta 2013, 2017 (Hawks 100-91, Series: Atlanta 2-0) Last Meeting: April 25, 2017, at Toyota Center (Rockets 105-99, Series: Houston 4-1) Boston 5-16 4-6 1-10 0-4 Years Played: 1975, 1980, 1981, 1986 Orlando 4-0 2-0 2-0 1-0 Last Meeting: June 8, 1986, at Boston Year Played: 1995 (Celtics 114-97, Series: Boston 4-2) Last Meeting: June 14, 1995, at The Summit (Rockets 113-101, Series: Houston 4-0) Dallas 8-8 4-4 4-4 1-2 Years Played: 1988, 2005, 2015 Philadelphia 2-4 1-2 1-2 0-1 Last Meeting: Apr. 28, 2015, at Toyota Center Year Played: 1977 (Rockets 103-94, Series: Rockets 4-1) Last Meeting: May 17, 1977, at The Summit (76ers 112-109, Series: Philadelphia 4-2) Denver 4-2 3-0 1-2 1-0 Year Played: 1986 Phoenix 8-6 4-3 4-3 2-0 Last Meeting: May 8, 1986, at Denver Years Played: 1994, 1995 (Rockets 126-122, 2OT, Series: Houston 4-2) Last Meeting: May 20, 1995, at Phoenix (Rockets 115-114, Series: Houston 4-3) Golden State 7-16 6-5 1-10 0-3 Year Played: 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 Portland 12-8 8-2 4-6 3-1 Last Meeting: May 10, 2019, at Toyota Center Years Played: 1987, 1994, 2009, 2014 (Warriors 118-113), Series: Warriors 4-2) Last Meeting: May 2, 2014, at Portland (Blazers 99-98, Series: Houston 4-2) L.A.