A Little Slice of the Moon: Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAY COLT Barn 45 Hip No

Consigned by Wavertree Stables, Inc. (Ciaran Dunne), Agent XVIII Hip No. Barn 108 BAY COLT 45 Foaled April 6, 2010 Mr. Prospector Gone West ........................ Secrettame Elusive Quality.................. Hero's Honor Touch of Greatness ........... Ivory Wand BAY COLT Danzig Green Desert..................... Foreign Courier Brocatelle (GB) ................. (1996) Habitat Brocade............................. Canton Silk By ELUSIVE QUALITY (1993). Black-type winner of $413,284, Poker H. [G3]- nwr, etc. Leading sire, sire of 11 crops of racing age, 1547 foals, 1025 starters, 72 black-type winners, 696 winners of 1865 races and earning $66,936,931, including champions Smarty Jones ($7,613,155, Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $5,884,800), etc.), Sepoy ($3,990,138, AAMI Golden Slipper [G1], etc.), Maryfield [G1] ($1,334,331), Elusive Kate [G1] (4 wins, $332,597), and of Raven’s Pass [G1] (hwt. at 3 in England, $3,658,556). 1st dam BROCATELLE (GB), by Green Desert. Placed in 2 starts at 3, €3,049, in France; placed in 2 starts at 3 in England. (Total: $4,136). Dam of 9 other registered foals, 9 of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2012, 8 to race, 3 winners-- Fusaichi Hokutosei (IRE) (c. by Machiavellian). 6 wins, 2 to 5, ¥150,299,000, in Japan, 2nd Baden-Baden Cup, 3rd Keio Hai Nisai S. (Total: $1,358,504). Ahlaain (c. by Bernstein). Winner at 2, £11,653, in England, 3rd Weather- bys Bank Stonehenge S.; placed at 3 and 4, 2012, 343,384 dirhams, in U.A.E., 2nd Emirates Airline Al Bastakiya S., Al Taher Motors Meydan Classic. -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Drama Recommended Monologues

Bachelor of Creative Arts (Drama) Recommended Monologues 1 AUDITION PIECES – FEMALE THREE SISTERS by Anton Chekhov IRINA: Tell me, why is it I’m so happy today? Just as if I were sailing along in a boat with big white sails, and above me the wide, blue sky and in the sky great white birds floating around? You know, when I woke up this morning, and after I’d got up and washed, I suddenly felt as if everything in the world had become clear to me, and I knew the way I ought to live. I know it all now, my dear Ivan Romanych. Man must work by the sweat of his brow whatever his class, and that should make up the whole meaning and purpose of his life and happiness and contentment. Oh, how good it must be to be a workman, getting up with the sun and breaking stones by the roadside – or a shepherd – or a school-master teaching the children – or an engine-driver on the railway. Good Heavens! It’s better to be a mere ox or horse, and work, than the sort of young woman who wakes up at twelve, and drinks her coffee in bed, and then takes two hours dressing…How dreadful! You know how you long for a cool drink in hot weather? Well, that’s the way I long for work. And if I don’t get up early from now on and really work, you can refuse to be friends with me any more, Ivan Romanych. 2 HONOUR BY JOANNA MURRAY-SMITH SOPHIE: I wish—I wish I was more… Like you. -

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by Godolphin

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by Godolphin Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock Q, Box 343 Nureyev (USA) Polar Falcon (USA) 140 (WITH VAT) Marie d'Argonne (FR) Pivotal (GB) Cozzene (USA) SILENT MORNING Fearless Revival (GB) Stufida (2016) Gone West (USA) Elusive Quality A Bay Filly Touch of Greatness Veil of Silence (IRE) (USA) (USA) (2006) Sadler's Wells (USA) Gossamer (GB) Brocade SILENT MORNING (GB), unraced, Own sister to HUSHING (GB). 1st Dam VEIL OF SILENCE (IRE), unraced; dam of four winners from 4 runners and 8 foals of racing age viz- SOUND AND SILENCE (GB) (2015 g. by Exceed And Excel (AUS)), won 4 races at 2 years at home and in France and £187,122 including Prix Eclipse, Maisons-Laffitte, Gr.3, Julia Graves Roses Stakes, York, L. and Windsor Castle Stakes, Ascot, L., placed 6 times including second in Godolphin Cornwallis Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, Prix d'Arenberg, Chantilly, Gr.3 and Qatar Juvenile Turf Sprint Stakes, Del Mar, L. SILENT BULLET (IRE) (2011 g. by Exceed And Excel (AUS)), won 2 races at 2 years and £38,678 and placed 3 times. HUSHING (GB) (2014 f. by Pivotal (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years and placed 4 times. STAY SILENT (IRE) (2012 f. by Cape Cross (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and placed twice, all her starts. Silent Morning (GB) (2016 f. by Pivotal (GB)), see above. (2017 f. by Dubawi (IRE)). She also has a 2018 filly by Exceed And Excel (AUS). 2nd Dam GOSSAMER (GB), Champion 3yr old filly in Ireland in 2002, won 4 races at 2 and 3 years and £322,559 including Meon Valley Stud Fillies' Mile Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, Entenmann's Irish 1000 Guineas, Curragh, Gr.1 and Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3, placed once viz third in Netjets Prix du Moulin de Longchamp, Longchamp, Gr.1; Own sister to BARATHEA (IRE); dam of seven winners from 7 runners and 11 foals of racing age including- IBN KHALDUN (USA) (c. -

Table of Contents

On s V·v" tage Artlerican The lth I r- B ater A _.. tP lac!( J ~~ls For Yoll 0llrney d table of Contents: Letter from the Producer ..... ......................................................... 3 Before You Go .......................................................................4 Theater Etiquette ....................................................................... 5 Scenic Breakdown .......................................................................6 Synopsis ................................................................................ ? Touchstones ........................................................................... 8 & 9 After the Show 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 •• 0 000 0 0 00 0 000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 000 0 •• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 •••• 00 •• 10 Interdisciplinary Activities ............................................ ......... 11 & 12 Acrostic 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ••• 00 0 0 0 0 0 00 0 00 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.13 Think Theatrically ..................................................................... 14 Fan Letter 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00 00 0 •• 0 00 0 ••• 0 0 00 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 •• 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00 0 0 0 0 ••• 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.15 Theater Vocabulary ..................................................................... 16 Write a Review ..................... ................................................ 17 Careers in the Arts ..................................................................... 18 African Americans in the Performing Arts .................................... 19 & 20 Draw a Picture ............ .................................................................. 21 Crossword ....................................................................................22 Supplemental Reading ..................................................... -

Beets Documentation Release 1.5.1

beets Documentation Release 1.5.1 Adrian Sampson Oct 01, 2021 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Guides..................................................3 1.2 Reference................................................. 14 1.3 Plugins.................................................. 44 1.4 FAQ.................................................... 120 1.5 Contributing............................................... 125 1.6 For Developers.............................................. 130 1.7 Changelog................................................ 145 Index 213 i ii beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 Welcome to the documentation for beets, the media library management system for obsessive music geeks. If you’re new to beets, begin with the Getting Started guide. That guide walks you through installing beets, setting it up how you like it, and starting to build your music library. Then you can get a more detailed look at beets’ features in the Command-Line Interface and Configuration references. You might also be interested in exploring the plugins. If you still need help, your can drop by the #beets IRC channel on Libera.Chat, drop by the discussion board, send email to the mailing list, or file a bug in the issue tracker. Please let us know where you think this documentation can be improved. Contents 1 beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Guides This section contains a couple of walkthroughs that will help you get familiar with beets. If you’re new to beets, you’ll want to begin with the Getting Started guide. 1.1.1 Getting Started Welcome to beets! This guide will help you begin using it to make your music collection better. Installing You will need Python. Beets works on Python 3.6 or later. • macOS 11 (Big Sur) includes Python 3.8 out of the box. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Tour De France, 1986

SLAYING THE BADGER GREG LEMOND, BERNARD HINAULT AND THE GREATEST TOUR DE FRANCE RICHARD MOORE Copyright © 2012 by Richard Moore All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moore, Richard. Slaying the badger: Greg Lemond, Bernard Hinault, and the greatest Tour de France / Richard Moore. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-934030-87-5 (pbk.) 1. Tour de France (Bicycle race) (1986) 2. LeMond, Greg. 3. Hinault, Bernard, 1954– 4. Cyclists—France—Biography. 5. Cyclists—United States—Biography. 6. Sports rivalries. I. Title.= GV1049.2.T68M66 2012 796.620944—dc23 2012000701 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210 ext. 2138 or visit www.velopress.com. Cover design by Landers Miller Design, LLC Interior design and composition by Anita Koury Cover photograph by AP Photo/Lionel Cironneau Interior photographs by Offside Sports Photography except first insert, page 2 (top): Corbis Images UK; page 5 (top): Shelley Verses; second insert, page 2 (bottom): Graham Watson; page 8 (top right): Pascal Pavani/AFP/Getty Images; page 8 (bottom): James Startt Text set in Minion. -

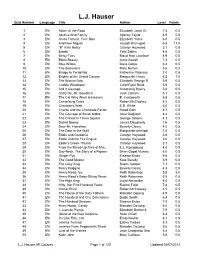

AR Quizzes for L.J. Hauser

L.J. Hauser Quiz Number Language Title Author Level Points 1 EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gr 7.4 0.5 2 EN All-of-a-Kind Family Sydney Taylor 4.9 0.5 3 EN Amos Fortune, Free Man Elizabeth Yates 6.0 0.5 4 EN And Now Miguel Joseph Krumgold 6.8 11.0 5 EN "B" is for Betsy Carolyn Haywood 3.1 0.5 6 EN Bambi Felix Salten 4.6 0.5 7 EN Betsy-Tacy Maud Hart Lovelace 4.9 0.5 8 EN Black Beauty Anna Sewell 7.3 0.5 9 EN Blue Willow Doris Gates 6.4 0.5 10 EN The Borrowers Mary Norton 5.6 0.5 11 EN Bridge to Terabithia Katherine Paterson 7.0 0.5 12 EN Brighty of the Grand Canyon Marguerite Henry 6.2 7.0 13 EN The Bronze Bow Elizabeth George S 5.9 0.5 14 EN Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink 5.6 0.5 15 EN Call It Courage Armstrong Sperry 5.0 0.5 16 EN Carry On, Mr. Bowditch Jean Latham 5.1 0.5 17 EN The Cat Who Went to Heaven E. Coatsworth 5.8 0.5 18 EN Centerburg Tales Robert McCloskey 5.2 0.5 19 EN Charlotte's Web E.B. White 6.0 0.5 20 EN Charlie and the Chocolate Factor Roald Dahl 6.7 0.5 21 EN The Courage of Sarah Noble Alice Dalgliesh 4.2 0.5 22 EN The Cricket in Times Square George Selden 4.3 0.5 23 EN Daniel Boone James Daugherty 7.6 0.5 24 EN Dear Mr. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C.