Noam Chomsky’S 90Th Birthday I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Is Language Typology Possible?

Why is language typology possible? Martin Haspelmath 1 Languages are incomparable Each language has its own system. Each language has its own categories. Each language is a world of its own. 2 Or are all languages like Latin? nominative the book genitive of the book dative to the book accusative the book ablative from the book 3 Or are all languages like English? 4 How could languages be compared? If languages are so different: What could be possible tertia comparationis (= entities that are identical across comparanda and thus permit comparison)? 5 Three approaches • Indeed, language typology is impossible (non- aprioristic structuralism) • Typology is possible based on cross-linguistic categories (aprioristic generativism) • Typology is possible without cross-linguistic categories (non-aprioristic typology) 6 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Franz Boas (1858-1942) The categories chosen for description in the Handbook “depend entirely on the inner form of each language...” Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction to The Handbook of American Indian Languages. 7 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) “dans la langue il n’y a que des différences...” (In a language there are only differences) i.e. all categories are determined by the ways in which they differ from other categories, and each language has different ways of cutting up the sound space and the meaning space de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1915. Cours de linguistique générale. 8 Example: Datives across languages cf. Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison 9 Example: Datives across languages 10 Example: Datives across languages 11 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Peter H. Matthews (University of Cambridge) Matthews 1997:199: "To ask whether a language 'has' some category is...to ask a fairly sophisticated question.. -

ED332504.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 332 504 FL 018 885 AUTHOR Davison, Alice, Ed.; Eckert, Penelope, Ed. TITLE Women in the Linguistics Profession: The Cornell Lectures. Conference on Women in Linguistics (Ithaca, New York, June 1989). INSTITUTION Linguirtic Society of America, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 90 CONTRACT NSF-88-00534 NOTE 268p.; Produced by the Committee on the Status of Women in Linguistics. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Attitudes; *Cultural Isolation; Deans; Doctoral Dissertations; *Employment Patterns; English Departments; *Females; Graduate Study; Higher Education; :,;tellectual Disciplines; *Linguistics; Mentors; Scnolarship; *Sex Bias; F.exual Harassment; Tenure; Trend Analysis; *Women Fulty; Work Environment ABSTRACT Papers on women in linguistics are presented in five groups. An introductory section contains: "Feminist Linguistics:A Whirlwind Tour"; "Women in Linguistics: The Legacy of Institutionalization"; "Reflections on Women in Linguistics";and "The Structure of the Field and Its Consequences forWomen." Papers on trends and data include: "The Status of Women in Linguistics"; "The Representation of Women in Linguistics, 1989"; and"Women in Linguistics: Recent Trends." A section on problems and theirsources includes: "How Dick and Jane Got Tenure: Women and UniversityCulture 1989"; "Success and Failure: Expectations andAttributions"; "Personal and Professional Networks"; "Sexual Harassmentand the University -

June, 2009 VITA Thomas G. Bever Education

June, 2009 VITA Thomas G. Bever Education Harvard College - A.B., 1961 Massachusetts Institute of Technology - Ph.D., 1967 Honors and Awards Phi Beta Kappa - Harvard University - 1961 "Magna cum laude with highest honors in Linguistics and Psychology"- Harvard College - 1961 NIH Predoctoral Fellowship - 1962-1964 Elected to Harvard Society of Fellows - 1964-1967 NSF Faculty Fellowship - 1974-1977 (Summers) Guggenheim Fellowship - 1976/77 Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences - 1984/85 The Foreign Language Teaching Research Article Award – 2004 – Society for Foreign Language Teaching in China. (Given every 2 years). The Compassionate Friends Award – 2005- “Compassionate employer of the year” Teaching Experience Lecturer, M.I.T., Psychology Department, 1964-1966 Assistant Professor, The Rockefeller University, 1967-1969 Associate Professor, The Rockefeller University, 1969-1970 Professor of Linguistics and Psychology, Columbia University, 1970-1986 Pulse Professor of Psychology, University of Rochester, 1985-1995 Professor of Linguistics, University of Rochester, 1985-1995 Research Professor of Cognitive Science, Linguistics, Neuroscience, Psychology, Language Reading and Culture. University of Arizona, 1995 - present Visiting Professor, USC, Spring 2005 Visiting Professor, University of Leipzig, Fall 2005 Visiting Professor, University of California, Irvine, Spring 2006 Administrative-Academic Activities Vice President, The Rockefeller University Chapter of American Association of University Professors, 1969-1970 -

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

Curriculum Vitae: Bruce P. Hayes

Curriculum Vitae: Bruce P. Hayes Address: Department of Linguistics, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/hayes/ Telephone: (310) 825-9507 (office) (310) 825-0634 (Linguistics Dept.) Education: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1976-1980, Ph.D., Linguistics Harvard University, 1973-1976, B.A. cum laude, Linguistics and Applied Mathematics Employment Distinguished Professor, Dept. of Linguistics, UCLA, 2012- history: Professor, Dept. of Linguistics, UCLA, 1989- Associate Professor, Dept. of Linguistics, UCLA, 1985-1989 Assistant Professor, Dept. of Linguistics, UCLA, 1981-1985 Lecturer, Dept. of Linguistics, Yale University, 1980-1981 UCLA Linguistics 1 “Introduction to Language” courses Linguistics 20 “Introduction to Linguistics” taught: Linguistics 88B “Linguistics and Verse Structure” Linguistics 103 “Introduction to General Phonetics” Linguistics 120A “Phonology I” Linguistics 191 “Metrics” Linguistics 200A “Phonological Theory I” Linguistics 201 “Phonological Theory II” Linguistics 205 “Morphology” Linguistics 210 “Field Methods” (with Paul Schachter) Linguistics 251 “The Phonology of Syllables and Stress” Linguistics 251 “CV Phonology” Linguistics 251 “The Metrical Theory of Stress” Linguistics 251 “Lexical Phonology” Linguistics 251 “Segment Structure” Linguistics 251 “The Syntax-Phonology Interface” Linguistics 251 “Phonetic Rules” Linguistics 251 “Intonation” Linguistics 251 “Metrics” Linguistics 251 “Phonetically-Driven Optimality-Theoretic Phonology” -

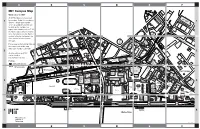

Campusmap06.Pdf

A B C D E F MIT Campus Map Welcome to MIT #HARLES3TREET All MIT buildings are designated .% by numbers. Under this numbering "ROAD 1 )NSTITUTE 1 system, a single room number "ENT3TREET serves to completely identify any &ULKERSON3TREET location on the campus. In a 2OGERS3TREET typical room number, such as 7-121, .% 5NIVERSITY (ARVARD3QUARE#ENTRAL3QUARE the figure(s) preceding the hyphen 0ARK . gives the building number, the first .% -)4&EDERAL number following the hyphen, the (OTEL -)4 #REDIT5NION floor, and the last two numbers, 3TATE3TREET "INNEY3TREET .7 43 the room. 6ILLAGE3T -)4 -USEUM 7INDSOR3TREET .% 4HE#HARLES . 3TARK$RAPER 2ANDOM . 43 3IDNEY 0ACIFIC 3IDNEY3TREET (ALL ,ABORATORY )NC Please refer to the building index on 0ACIFIC3TREET .7 .% 'RADUATE2ESIDENCE 3IDNEY 43 0ACIFIC3TREET ,ANDSDOWNE 3TREET 0ORTLAND3TREET 43 the reverse side of this map, 3TREET 7INDSOR .% ,ANDSDOWNE -ASS!VE 3TREET,OT .7 3TREET .% 4ECHNOLOGY if the room number is unknown. 3QUARE "ROADWAY ,ANDSDOWNE3TREET . 43 2 -AIN3TREET 2 3MART3TREET ,ANDSDOWNE #ROSS3TREET ,ANDSDOWNE 43 An interactive map of MIT 3TREETGARAGE 3TREET 43 .% 2ESIDENCE)NN -C'OVERN)NSTITUTEFOR BY-ARRIOTT can be found at 0ACIFIC "RAIN2ESEARCH 3TREET,OT %DGERTON (OUSE 'ALILEO7AY http://whereis.mit.edu/. .7 !LBANY3TREET 0LASMA .7 .7 7HITEHEAD !LBANY3TREET )NSTITUTE 0ACIFIC3TREET,OT 3CIENCE .7 .! .!NNEX,OT "RAINAND#OGNITIVE AND&USION 0ARKING'ARAGE Parking -ASS 3CIENCES#OMPLEX 0ARSONS .% !VE,OT . !LBANY3TREET #ENTER ,ABORATORY "ROAD)NSTITUTE 'RADUATE2ESIDENCE .UCLEAR2EACTOR ,OT #YCLOTRON ¬ = -

Campus Map, Shuttle Routes & Parking

CAMPUS MAP, SHUTTLE ROUTES & PARKING SHUTTLE STOPS REUNION SHUTTLES SCHEDULE CAMPUS PARKING LOTS Tech Reunions Shuttle – red route Thursday, June 8 Saturday, June 10 and Sunday June 11 Four vehicles will service the Tech Reunions route (marked red on the map), All day: NW23 C, NW30 D, NW86 E, Waverly Lot F, All day: 158 Mass. Ave. Lot A, Albany Garage B, 1 Kresge/Maseeh Hall and one will service the MIT Museum route (marked blue on the map) the Westgate Lot (limited space) G, NW23 C, NW30 D, NW86 E, Waverly Lot F, 2 Burton House following hours: After 2:30 p.m.: West Lot H Westgate Lot G, West Lot H, West Garage I, 3 Westgate Parking Lot Kresge Lot J, Tang Center Lot (ungated lot) K Thursday, June 8: 2:00 p.m.–10:00 p.m. Friday, June 9 4 Hyatt Regency/W92 All day: NW23 C, NW30 D, NW86 E, Waverly Lot F, 5 Friday, June 9: 7:00 a.m.–7:30 p.m., then 11:00 p.m.–1:00 a.m. Parking for Registration and Check-in Simmons Hall G, *Please note that service to stops 1, 2, 3, 12, and 13 will be suspended from Westgate Lot (limited space) 20-minute parking is available in the Student Center 6 Johnson Athletics Center H, 9:00–10:30 a.m. for the Commencement procession. The MIT Museum Shuttle After 2:30 p.m.: West Lot West Garage I turnaround R1 , and in front of McCormick Hall R2 . Charles Street 7 Vassar Street at Mass Ave. -

An Interview with Noam Chomsky

FORUM The Interesting Part Is What Is Not Conscious: An Interview with Noam Chomsky Michael M. Schiffmann The following is the transcription of an interview held on 23 January 2013 at Chomsky’s MIT office in Cambridge, MA, between Michael Schiffmann (MS, in italics) and Noam Chomsky (NC, in regular typeface). OK, it’s January the 23rd, we are at the MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This will be a 60 minute interview with Noam Chomsky on the sixty to sixty-five years of his work, and we will try to cover as many topics as possible. To start off with this, I should put this into a context. I first started to interview Noam Chomsky about this [i.e. the history of generative grammar] two and a half years ago, right here at the MIT, and inadvertently, this grew into a whole series, and today’s interview is meant to be the end of the series, but not, hopefully, the end of our talks. [Both laugh.] Well, as I see it, and that’s a central part of the research project on your work I’m working on, there are, among many others, several red threads that run through your work, and that would be, first, the quest for simplicity in scientific description, and as we will see, that has several aspects, then the question of abstractness, which we will see in comparison to what went on before and what you started to work with. A closely related question that came to the forefront later was locality, local relations in mental computations. -

Interview with Noam Chomsky

INTERVIEW WITH NOAM CHOMSKY Alessandro Boechat de Medeiros1 Avram Noam Chomsky is a world-renowned linguist, philosopher and political activist. He is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Linguistics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and recently became a laureate Professor in the Department of Linguistics at University of Arizona. He has been the leader of the generative enterprise in linguistic theory since its beginning, in the late fifties, and is considered by many the father of modern Linguistics. In fact, his views have influenced the whole field and established points of departure for research in formal syntax, phonology and even semantics. Born in Philadelphia, in 1928, Chomsky started his undergraduate studies in Philosophy and Linguistics at the University of Philadelphia, in 1945. He concluded his Ph.D. in Linguistics in 1955, under the supervision of Zellig Harris, at the same University, with the thesis The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, a revolutionary work only published in 1975. Two years later, in 1957, he published Syntactic Structures (SS), one of his most famous linguistics books, considered by many a true revolution in the field. SS was in part based on The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, and exerted a great influence during late fifties and early sixties among language scholars, defining to a great extent linguistics research developed in the years to come. In 1959 he published his famous review of B. F. Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior. The review presents a frontal and exhaustive critique of the behaviorist theory in a general way and also focally regarding language. Chomsky had other defining theoretical debates with Philosopher Michel Foucault2 and with Psychologist Jean Piaget3. -

The Language Faculty – Mind Or Brain?

The Language Faculty – Mind or Brain? TORBEN THRANE Aarhus University, School of Business, Denmark Artiklens sigte er at underkaste Chomskys nyskabende nominale sammensætning – “the mind/brain” – en nøjere undersøgelse. Hovedargumentet er at den skaber en glidebane, således at det der burde være en funktionel diskussion – hvad er det hjernen gør når den behandler sprog? – i stedet bliver en systemdiskussion – hvad er den interne struktur af den menneskelige sprogevne? Argumentet søges ført igennem under streng iagttagelse af de kognitive videnskabers opfattelse af information og repræsentation, specielt som forstået af den amerikanske filosof Frederick I. Dretske. 1. INTRODUCTION Cartesian dualism is dead, but the central problems it was supposed to solve persist: What kinds of substances exist? Are bodily things (only) physical, mental ‘things’ (only) metaphysical? How is the mental related to the physical? Although “we are all materialists now”, such questions still need answers, and they still need answers from within realist and naturalist bounds to count as scientific. Linguistics is a discipline that may be expected to contribute with answers to such questions. No one in their right mind would deny that our ability to acquire and use human language is lodged between our ears – inside our heads. That is, in our brains and/or minds. In some quarters it has been customary for the past 50 odd years or so to regard this ability as a distinct and dedicated cognitive ability on a par with our abilities to see (vision) or to keep our balance (equilibrioception), and to refer to it as the Human Language Faculty (HLF). This has been the axiomatic starting point for the development of main stream generative linguistics as founded by Chomsky in 1955 in what I shall refer to as ‘Chomsky’s programme’. -

1 RELEVANCE THEORY Deirdre Wilson to Appear in Y. Huang (Ed.)

1 RELEVANCE THEORY Deirdre Wilson To appear in Y. Huang (ed.) Oxford Handbook of Pragmatics. Oxford University Press. Published online Jan 2016: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697960.013.25 Abstract This paper outlines the main assumptions of relevance theory (while attempting to clear up some common objections and misconceptions) and points out some new directions for research. After discussing the nature of relevance and its role in communication and cognition, it assesses two alternative ways of drawing the explicit–implicit distinction, compares relevance theory’s approach to lexical pragmatics with those of Grice and neo- Griceans, and discusses the rationale for relevance theory’s conceptual–procedural distinction, reassessing the notion of procedural meaning in the light of recent research. It ends by looking briefly at the relation between the capacity to understand a communicator’s meaning, on the one hand, and the capacity to assess her reliability and the reliability of the communicated content, on the other, and considers how these two capacities might interact. Keywords: Relevance, communication, explicatures, lexical pragmatics, procedural meaning 1. Introduction One of the most original features of Grice’s approach to communication was his view that meaning is primarily a psychological phenomenon and only secondarily a linguistic one: for him, speaker’s meanings are basic and sentence meanings are ultimately analysable in terms of what speakers mean (Grice 1957, 1967). Despite this reference to psychology, Grice’s goals were mainly philosophical or semantic: his analysis of speaker’s meaning was intended to shed light on traditional semantic notions such as sentence meaning and word meaning, and his accounts of the derivation of implicatures were rational reconstructions of how a speaker’s meaning might be inferred, rather than empirical hypotheses about what actually goes on in hearers’ minds. -

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky Addressing a Crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky addressing a crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989. Noam Chomsky A Life of Dissent Robert F. Barsky ECW PRESS Copyright © ECW PRESS, 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process—electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW PRESS. CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Barsky, Robert F. (Robert Franklin), 1961- Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55022-282-1 (bound) ISBN 1-55022-281-3 (pbk.) 1. Chomsky, Noam. 2. Linguists—United States—Biography. I. Title. P85.C47B371996 410'.92 C96-930295-9 This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and with the assistance of grants provided by the Ontario Arts Council and The Canada Council. Distributed in Canada by General Distribution Services, 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2T6. Distributed in the United States and internationally by The MIT Press. Photographs: Cover (1989), frontispiece (1989), and illustrations 18, 24, 25 (1989), © Elaine Briere; illustration 1 (1992), © Donna Coveney, is used by per- mission of Donna Coveney; illustrations 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20,21,22,23,26, © Necessary Illusions, are used by permission of Mark Achbar and Jeremy Allaire; illustrations 5, 8, 9, 10 (1995), © Robert F.