How Not to Climb a Glaciated Peak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tacoma Intermediate Snow Skills Curriculum 2019

Tacoma Intermediate Snow Skills Curriculum 2019 Purpose: Build competent basic glacier rope leaders ● Ensure Intermediate student understanding and knowledge of basic skills/topics so they may adequately teach basic students ● Build on student knowledge of basic skills: ○ Critical thinking through the steps of crevasse rescue and the haul systems ○ Snow anchors ○ Snow belays ● Discuss circumstances and decision making on a glacier climb ● Start introducing 2 person team travel ● Building the community - Have a good time and give the students a chance to get to know each other. Required Reading: Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, 9th Edition, Chapter 3 - Camping, Food, and Water Chapter 16 - Snow Travel and Climbing Chapter 17 - Avalanche Safety Chapter 18 - Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue Chapter 27 - The Cycle of Snow Snow Anchors for Belaying and Rescue. D. Bogie, A. Fortini. Backing up an Anchor for Crevasse Rescue. L. Goldie. Self Arrest with Crampons. J. Martin. Drop Loop Crevasse Rescue by Gregg Gagliardi Crevasse rescue videos by AMGA instructor Jeff Ward: ● How to Rope Up for Glacier Travel ● How to Transfer a Fallen Climber's Weight to a Snow Anchor for Crevasse Rescue ● How to Back Up a Snow Anchor for Crevasse Rescue ● How to Rappel Into and Ascend Out of a Crevasse ● How to Prepare a Crevasse Lip for Rescue ● How to Haul a Climber Out of a Crevasse Recommended Reading: Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain, 2nd edition. Bruce Tremper, ISBN 1594850844 Snow Sense. J.Fredston and D.Fester, ISBN 0964399407 Snow Travel: Skills for Climbing, Hiking, and Moving Over Snow. M. Zawaski. General design principles 1. -

Seattle the Potential for More Depth and Richness Than Any Other Culture I Can Think Of

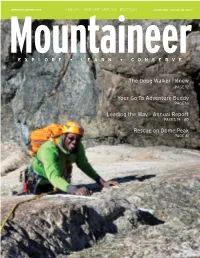

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG ANNUAL REPORT SPECIAL EDITION SPRING 2016 • VOLUME 110 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE The Doug Walker I Knew PAGE 12 Your Go-To Adventure Buddy PAGE 16 Leading the Way - Annual Report PAGES 19 - 40 Rescue on Dome Peak PAGE 41 2 mountaineer » spring 2016 tableofcontents Spring 2016 » Volume 110 » Number 2 Annual Report The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy 19 Leading the Way the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. The Mountaineers Annual Report 2015 Features 12 The Doug Walker I knew a special tribute by Glenn Nelson 16 Your Go-To Adventure Buddy an interview with Andre Gougisha 41 Rescue on Dome Peak Everett Mountaineers save the day 16 Columns 6 PEAK FITNESS reducing knee pain 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Tom Vogl 8 OUTDOOR EDUCATION from camper to pioneer 10 SAFETY FIRST VHF radios and sea kayaking 14 CONSERVATION CURRENTS our four conservation priorities 46 RETRO REWIND Wolf Bauer - a wonderful life 50 BRANCHING OUT your guide to the seven branches 52 GO GUIDE activities and courses listing 60 OFF BELAY 41 celebrating lives of cherished members 63 LAST WORD explore by Steve Scher Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates as Discover The Mountaineers a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various nonprofit If you're thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where organizations. to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of Mountaineer uses: informational meetings at each of our seven branches. -

2019 Work Catalog

FIRE & RESCUE / CLIMB / TOWER TACTICAL / ROPE ACCESS / ARBOR WORK 2019 The top triangle embodies the will of humanity and the drive to ascend ever upward. Aiding people in the battle against the negative force of gravity is at the center of Sterling's reason for being. When you can be bold, courageous and safe, you can own the moment. We call that Freedom to Focus. The bottom triangle serves as the force of gravity, seeking always to ground us. 2019 FEATURED PRODUCT Escape System Lightning GT Unparalleled performance. Unmatched customization. At Sterling we’re dedicated to fire fighter safety. We pioneered the development of escape systems SafeD™ that allow rapid egress and self- Carabiner rescue – all built on the foundation of our proven, trusted ropes. The FCX Escape System is our latest innovation designed around FCX™ Device the needs of fire fighters and departments. FireTech2 Rope Abrasion Resistant Reinforced Pocket Bag A portion of every Sterling FCX Escape System sold is donated to the Lt. Joseph P. DiBernardo Memorial Foundation. Proudly For additional details, specifications, and Certified to 1983 Made in U.S.A. customization options see page 36 or contact NFPA Escape System with U.S. and Globally Sourced Material our sales team. Our Pledge is Simple We have committed to ourselves and to those who use and rely on our products that we’ll never compromise quality; we’ll never stop innovating real-world solutions, and we’ll deliver the most reliable equipment possible. At Sterling, we’re proud to design and build all of our Life- Safety Rope under one roof in Biddeford, Maine. -

Fall Into Crevasse - Traveling Unroped on a Glacier Alaska, St

AAC Publications Fall Into Crevasse - Traveling Unroped on a Glacier Alaska, St. Elias Range, Middle Peak At the end of March, I (Colin Haley, 28) left for a climbing trip in Alaska’s St. Elias Range with Portlanders John Frieh and Daniel Harro. We were flown into the range by Paul Claus midday on April 1. We spent a few hours setting up our base camp and then went for a short ski up-glacier to scope our objective. About 20 minutes out of camp, I suddenly broke through a totally hidden crevasse and fell approximately 15 meters, ricocheting off the walls of the crevasse. We had left for our leisurely ski with essentially no equipment, so Daniel immediately skied back to camp to fetch a rope, crampons, ice tools, and harnesses. I was able to climb out of the crevasse with a top-rope (and even managed to rescue my skis and poles). Fortunately, I escaped any truly serious injuries. Unfortunately, however, I had a fractured cheekbone and my trip was over. We skied back to camp and the next morning I flew off the glacier, for a total of about 16 hours in the St. Elias Range. John and Daniel graciously offered to fly out and help get me home, but I was confident I’d be alright, so I told them to stay and go climbing. This accident has undoubtedly made me more wary of glacier travel, even though it’s something I’ve been doing very regularly for over 15 years. I’m sure I will continue to do some occasional solo travel on glaciers, but I absolutely view solo glacier travel much more seriously now. -

Winter Crevasse Rescue and Glacier Travel Day 3 – Ski Mountainee

Day 1 – Winter Crevasse Rescue and Glacier Travel ● Lesson 1: Introduction to Glacier Kit ● Lesson 2: Equalized anchor, knots and rappelling ● Lesson 3: Ascending the rope – prussic, ratchet, reverse ● Lesson 4: Situational awareness, review hazards ● Lesson 5: Glacier travel rope handling & crevasse rescue ● Lesson 6: Dividing the rope ● Lesson 7: The prussik ● Lesson 8: Arresting the fall, holding the victim and anchor building ● Lesson 9: Backing up anchor and approaching the lip ● Lesson 10: Canadian drop loop system demo ● Lesson 11: Incorporating a ratchet ● Lesson 12: First raise method, z-pulley raising system, adding advantage. ● Lesson 13: Reversing the raise & lowering ● Lesson 14: Crevasse Rescue Scenario ● Lesson 15: Problem-solving specific scenario Day 2 – Winter Crevasse Rescue and Glacier Travel ● Lesson 16: Rope up point strategy (map & altimeter) & white out plan ● Lesson 17: Glacier formation, physiology, terminology and travel including rope handling and taking coils ● Lesson 18: Safe glacier travel route finding & track setting – crevasse avoidance, serac hazard mitigation, dealing with avalanche terrain, crevasse bridge integrity and evaluation ● Lesson 19: Traveling in echelon & belaying across crevasse bridges ● Lesson 20: Downhill glacier skiing safety strategy Day 3 – Ski Mountaineering Skills Day ● Lesson 1: “Snow and ice school” – introduction to ski mountaineering equipment, ski crampons and boot crampons, ice axe. ● Lesson 2: Ascending/descending and moving in steeper firmer/crusted/icy slopes. ● Lesson 3: Belaying and rappelling, anchors. ● Lesson 4: Roped vs. unroped terrain – belaying, rope management, short roping, boot packing, stowing the skis on the pack, ridge walking. Day 4 – Ski Mountaineering Skills Day ● Lesson 5: Ski mountaineering objective: situational awareness, route finding and track setting in Class 3 (complex) terrain. -

Breasts on the West Buttress Climbing the Great One for a Great Cause

Breasts on the West Buttress Climbing the Great One for a great cause Nancy Calhoun, Sheldon Kerr, Libby Bushell A Ritt Kellogg Memorial Fund Proposal Calhoun, Kerr, Bushell; BOTWB 24 Table of Contents Mission Statement and Goals 3 Libby’s Application, med. form, agreement 4-8 Libby’s Resume 9-10 Nancy’s Application, med. form, agreement 11-15 Nancy’s Resume 16-17 Sheldon’s Application, med. form, agreement 18-23 Sheldon’s Resume 24-25 Ritt Kellogg Fund Agreement 26 WFR Card copies 27 Travel Itinerary 28 Climbing Itinerary 29-34 Risk Management 35-36 Minimum Impact techniques 37 Gear List 38-40 First Aid Contents 41 Food List 42-43 Maps 44 Final Budget 45 Appendix 46-47 Calhoun, Kerr, Bushell; BOTWB 24 Breasts on the West Buttress: Mission Statement It may have started with the simple desire to climb North America’s tallest peak, but with a craving to save the world a more pressing concern on the minds of three Colorado College women (a Vermonter, an NC southern gal, and a life-long Alaskan), we realized that climbing Denali could and should be only a mere stepping stone to the much greater task at hand. Thus, we’ve teamed up with the American Breast Cancer Foundation, an organization that is doing their part to save our world, one breast at a time, in order to do our part, in hopes of becoming role models and encouraging the rest of the world to do their part too. So here’s our plan: We are going to climb Denali (Mount McKinley) via the West Buttress route in June of 2006. -

Clinic: Two-Person Glacier Travel & Solo Crevasse Rescue

Clinic: Two-Person Glacier Travel & Solo Crevasse Rescue Krzysztof Ostrowski last updated on 12/8/2019 Audience: climb leaders and 2nd and higher-year intermediate students Prerequisites: One of the following badges: Climb Leader, Intermediate Alpine Climbing Course, Intermediate Alpine Climbing Course Student Duration: 3-4 hours (one evening on a weekday, or preferably, half a day on a weekend) Location: Mountaineers Program Center (rappel stations at the north wall) Dates: first session ideally in mid-December, potentially again in January or February if there’s interest Number of students: 4-8 (rope teams of two, students should sign up with a partner) Number of instructors: 2-4 (ideally one instructor per rope team, minimum one per two rope teams) Cost: free Students will learn how to: ● Setup efficiently for glacier travel as a single two-person team: distance between climbers, knots on the rope (when to use, how to space), tie-in, kiwi coil, required gear. ● Arrest a fall and build a SERENE anchor while in arrest position, without relying on external help. ● Rappel into the crevasse, provide first-aid, attach drop loop, and reascend; use runners to extend drop loop if needed. ● Setup a 6:1 mechanical advantage system and haul the fallen climber out of the crevasse while removing slack. Primary sources/references: ● Canonical reference: The Mountain Guide Manual by Marc Chauvin, Rob Coppolillo ○ When confronted with confusing or contradictory advice, it’s safe to rely on this source. ● AMGA videos from Outdoor -

Mt. Rainier Required Equipment List

2019 International Mountain Guides Mt. Rainier Required Equipment List Thanks for choosing to climb with IMG. We look forward to climbing Mt. Rainier with you! The list below is designed to help you identify everything you will need on your trip. Keep in mind that is no perfect gear list. Everybody is different and every climb has a different weather forecast making it tough to answer every need with one gear list. The bottom line is if you stick to this list you’ll have everything you need. Each piece of gear is accompanied by a description to help you understand its use and a recommended example. All items on this list are there for a reason, and unless otherwise specified, they are required. Items available for rent from IMG's affiliate, Ashford LLC at our headquarters in Ashford are indicated on the list below by an asterisk (*). Rental items will be available on your check-in day. No need to reserve it in advance of your program. NOTE FOR MOUNTAIN DAY SCHOOLS (MDS), ADVANCED MOUNTAIN DAY SCHOOLS (AMDS) and CREVASSE RESCUE SCHOOLS (CRS): If you are signed up for the MDS or AMDS, please see this gear list » If you are taking the 2-Day Crevasse Rescue School, please see this gear list » See the Mt. Rainier MDS and Crevasse Rescue School Gear List PDF » ALL RAINIER CLIMBS: When you meet for your climb, your guides will inspect your gear and help you decide exactly what to bring. This could vary slightly from the list below depending on the route, guide personal preferences and forecasted weather. -

An Illustration of Crevasse Rescue

An Illustration of Crevasse Rescue - the one thousand steps you need to know to save your climbing partner without breaking your back 9th revision, the color coordinated version! updated 1/4/2012, compliant with the Freedom of the Hills 8th edition 3 3 / / W W 3 / W W Copyright Deling Ren 2010-2011. Created with Microsoft Visio ®. Thanks to all reviewers and http://www.visguy.com for the climber stencil. · A rope team travels on crevassed • terrain. · The leader (Ryan) probes the ground with his ice axe. · The team keeps slack out of the rope to minimize the length of a fall. Ryan Brooke Grace · Ryan falls into a crevasse, yelling • • “falling”. · All rope team members yell “falling” and arrest. Tips 1. First establish contact with the fallen climber. Ask if he's able to get out by himself. 2. If not, try other alternatives, e.g. direct pull, or a 2:1 system (C-pulley) before setting up a time consuming Z-pulley. 3. In the following steps, communicate with the fallen climber if possible, keep him informed of what’s going on. · Grace (end person) eases up as • • • Brooke (middle person) holds the weight of Ryan, the fallen climber. · Grace then comes down and passes Brooke using a prusik as her protection, probing with her ice axe. · Grace builds an initial anchor with a • • • • picket planted in the snow. · She connects the weighted rope to the anchor using a prusik hitch. · Brooke slowly transfers weight to the anchor. · Brooke moves down but still keeps in self arrest position. -

Mount Waddington Ski Mountaineering Equipment List

Summit Mountain Guides 250-354-4884 [email protected] Mount Waddington Ski Mountaineering Equipment list The equipment and clothing you bring will have a big impact on the quality of your trip. Make sure to bring all items listed except for items that are listed as optional (either are luxuries or your guide will be carrying for the group). Temperatures can vary widely in the springtime. They can increase from –20C overnight to +10C on sunny days. For clothing use the ‘layer system’: Light technical clothing that doesn’t take much space in your backpack and dries quickly if sweaty or wet. Layers that can be put on and taken off fast if weather conditions change during the day. If you have any questions about anything please contact us. Technical Equipment Alpine Touring skis (lightweight bindings like Dynafit or Silvretta Pure is recommended) Alpine touring boots (With Vibram sole) Ski poles (with regular powder baskets) Climbing skins (At least as wide as the waist of your ski) Avalanche transceiver (475 Megahertz with extra batteries) Lightweight snow shovel Avalanche probe Backpack, medium sized (about 45 liters) with rain cover (i.e. garbage bag) and outside straps to attach skis. Climbing harness for glacier travel 1 Ice Axe (preferably light weight with a maximum length of 60cm) Boot Crampons, lightweight if possible (i.e. aluminum) 2 locking carabiners (Your guide will bring a full set of Crevasse rescue equipment) 1 non-locking carabiners Prusik cords (2 times 5m length of 6mm cord) A 1m section of 6mm -

Crevasse Rescue Equipment List

Crevasse Rescue Equipment List Kaf Adventures will provide all group climbing gear. It is your responsibility to bring everything that is listed below. This list covers both our one-day Crevasse Rescue Course and our two-day, on snow course. If your course does not involve camping, please just bring the equipment for a single day. All gear that can be rented is marked with an *, optional gear is marked (o) Camping and Personal Gear ☐ Water Bottles, with at least 2 liters of capacity ☐ Toiletries; with a ziploc for any waste ☐ Headlamp and extra batteries ☐ Sunscreen; SPF 30 or more ☐ Lip balm ☐ Personal medications ☐ Lunches & snacks ☐ Backpack: 50-70L capacity* Clothing ☐ Long underwear (top & bottom) synthetic or wool ☐ Insulating pants (fleece or wool) ☐ Mid-weight sweater/vest (fleece or wool) ☐ Parka or puffy style jacket (synthetic or down) ☐ Rain jacket with hood ☐ Rain pants ☐ Warm hat that covers ears ☐ Sun hat with brim ☐ 2 gloves/mittens (one waterproof & one insulating) ☐ 2-3 pairs of socks (synthetic or Wool) ☐ Gaiters ☐ Stiff leather or plastic mountaineering boots* (3/4 shank & crampon compatible) ☐ Sunglasses w/ good side coverage ☐ Wind-breaker + pant (o) ☐ Neck gaiter/buff 2960 4th Avenue South Suite #115 Seattle, Washington 98134 206-413 -5418 [email protected] kafadventures.com Climbing Equipment ☐ Helmet* ☐ Ice axe* ☐ Crampons (make sure they fit your boots)* ☐ Harness* ☐ Glacier Rig Kit ☐ 3 Locking carabiners ☐ 2 Non-locking carabiners ☐ Double-length sewn runner (48”) ☐ 2 prussik cords, made of 5mm cord (1 cut to 6’ and 1 cut to 12’) Miscellanious Equipment ☐ Whistle (o) ☐ Pocketknife/Leatherman ☐ Extra nylon cord (25-50’) (o) ☐ Area maps and compass (o) ☐ Heavy duty plastic trash bags (for water-proofing) (o) ☐ Note pad/pencil ☐ Camera (o) ☐ Candle (o) ☐ Watch (o) ☐ Goggles (o) ☐ Half foam pad to stand/sit in snow (o) ☐ Shorts/t shirt (o) ☐ Extra stuff sacks (o) ☐ Bandana (o) ☐ Trekking Poles (o)* 2960 4th Avenue South Suite #115 Seattle, Washington 98134 206-413 -5418 [email protected] kafadventures.com. -

CLIMBS with MEDICAL and WEATHER COMPLICATIONS 347 • • Jungle of Heather, Birch and Rowan, Boulders and Peat, Which I Have Never Succeeded in Circumnavigating

CLIMBS WITH MEDICAL AND WEATHER COMPLICATIONS 347 • • jungle of heather, birch and rowan, boulders and peat, which I have never succeeded in circumnavigating. With Dr. Johnson, I have always felt that ' a walk upon ploughed fields in England is a dance upon carpets compared with the toilsome drudgery of wandering in Skye.' But for all the scratche~ the ridge remains the finest mountaineering • expedition in the British Isles. Or perhaps it is on4y the best but one ; for it has ·one . sad disadvantage· for the real hero. Its completeness is . spoilt by those two awkward outposts of the Black Coolin, isolated amongst the Red Coolin, Blaven and Clach Glas. Blaven is perversely just over 3000 feet high, so that for a gatherer of Munros a traverse of the main ridge leaves one· still to pluck. In June 1939, Charleson and Forde started from a camp at the foot of Gars Bheinn, traversed the whole of the main ridge to Sgurr na h'Uamha, with snow and ice part of the way ; and after a meal and a rest at a camp in Harta Corrie, went up Clach Glas and Blaven and came back to their tent in Harta Corrie, the whole expedition taking five minutes less than 24 hours. Three months later Murray and Donaldson, setting out from Glen Brittle, sustained by vita-glucose and revived with draug4ts of navy rum and Bovril, repeated the feat with half an hour to spare. So history once more repeats itself, and the finest expedition in the British Isles, already only a preliminary tC? an ascent of Blaven and Clach G las, is fast becoming an ' Easy Day for a Lady.' .